DeSci: A Revolution for the Future of Science, or an Unattainable Dream?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

DeSci: A Revolution for the Future of Science, or an Unattainable Dream?

DeSci may not be able to disrupt the traditional academic system, but it has the potential to play a complementary role in areas such as research funding, journal publishing, and data sharing.

Author: @100y_eth

Translation: Baishihua Blockchain

The academic system is deeply flawed, but DeSci is not a panacea.

Special thanks to @tarunchitra (Gauntlet), @NateHindman (Bio), and Benji @benjileibo (Molecule) for their feedback and review of this article.

I recently obtained a degree in chemical engineering and served as first author on four papers during my graduate studies, including publications in top-tier journals such as Nature sub-journals and the Journal of the American Chemical Society (JACS). Although my academic experience has been limited to the graduate level, having actively taken on the role of an independent researcher, I believe I may have uncovered some insights. Over nearly six years in academia, I've gained deep firsthand understanding of the systemic structural problems embedded within the academic ecosystem.

Against this backdrop, DeSci (Decentralized Science) aims to leverage blockchain technology to challenge the centralized flaws of traditional academia—an undoubtedly compelling concept. Recently, DeSci has ignited a wave of excitement in the crypto market, with many believing it holds the potential to completely disrupt the existing landscape of scientific research.

I, too, hope for such transformation. However, I believe the likelihood of DeSci fully replacing the traditional academic system is low. From a practical standpoint, DeSci is more likely to serve as a complementary force, helping address some core issues within the current academic framework.

Therefore, at the heart of this growing DeSci momentum, I aim to draw upon my academic experience to explore the structural problems inherent in traditional academia, assess whether blockchain technology truly offers effective solutions, and further examine the tangible impact DeSci might bring to the scientific community.

1. The Sudden Surge of DeSci

1) DeSci: From Niche Concept to Thriving Movement

The long-standing structural problems in academia are widely known. Articles like VOX’s “The Seven Biggest Problems in Science According to 270 Scientists” and “The War to Liberate Science” have thoroughly explored these issues. Over the years, various attempts have been made to tackle these challenges—some of which we will discuss later.

The concept of DeSci (Decentralized Science) emerged as an effort to use blockchain technology to solve these problems, but it only began gaining attention around 2020. Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong introduced the idea of DeSci to the crypto community through ResearchHub, attempting to realign research incentives via ResearchCoin (RSC).

However, due to the capital speculation nature of the crypto market, DeSci remained largely overlooked for a long time, championed only by a few small communities—until the emergence of pump.science.

2) The Butterfly Effect Triggered by pump.science

Source: pump.science

pump.science is a DeSci project on the Solana ecosystem developed by Molecule, a prominent DeSci platform. It functions both as a fundraising platform and leverages Wormbot technology to stream long-term experiments in real time. Users can propose compounds they believe could extend lifespan or purchase tokens linked to those ideas.

Once a token's market cap exceeds a set threshold, the team uses Wormbot devices to conduct experiments testing whether the compound actually extends the lifespan of test subjects. If the experiment succeeds, token holders gain rights related to that compound.

However, some community members have criticized this model, arguing that the experiments lack sufficient scientific rigor and are unlikely to meaningfully advance anti-aging drug development. Gwart expressed skepticism through satirical remarks, representing a cautious or even skeptical stance toward DeSci and challenging the claims made by its proponents.

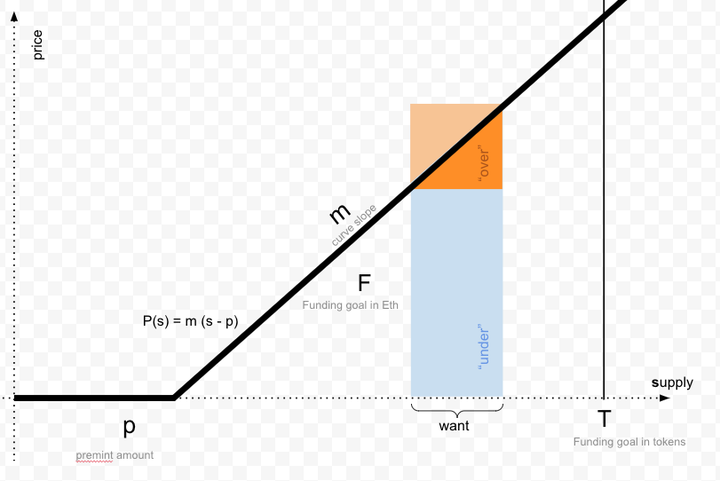

pump.science employs a Bonding Curve mechanism similar to Molecule’s model, where token prices rise as more users buy in.

The tokens launched by the project, such as RIF (for Rifampicin) and URO (for Urolithin A), coincided perfectly with the meme token craze in the crypto market, causing their prices to skyrocket. This unexpected surge brought DeSci into the public spotlight. Ironically, what propelled DeSci into popularity wasn't its scientific vision, but rather the price explosion driven by token speculation—sparking the current wave of interest in DeSci.

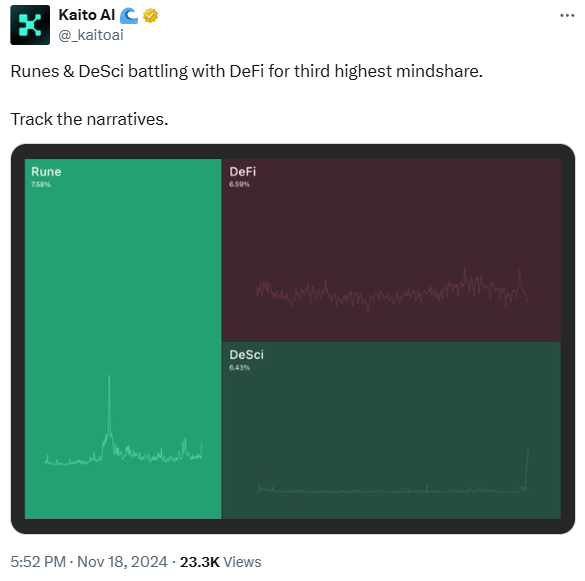

Source: @KaitoAI

In the fast-moving crypto market, DeSci had long been a niche area. Yet in November 2024, it suddenly became one of the hottest narratives. Not only did pump.science-related tokens surge in price, but Binance also announced investment in Bio, a DeSci grant protocol, while other established DeSci tokens saw significant gains—marking a pivotal moment for DeSci.

2. Flaws in Traditional Science

It’s no exaggeration to say that academia suffers from numerous systemic and severe problems. Throughout my academic career, I often wondered: how does such a flawed system continue to function? Before exploring DeSci’s potential, let’s first examine the shortcomings of the traditional academic system.

1) Systemic Challenge One: Research Funding

A. Evolution of Research Funding

Prior to the 19th century, scientists secured funding very differently than today, primarily relying on two models:

Patronage: European monarchs and nobles often sponsored scientists to enhance their prestige and advance science. For example, Galileo was supported by the Medici family, enabling him to continue developing telescopes and conducting astronomical research. Religious institutions also played a role; during the Middle Ages, churches and clergy funded research in astronomy, mathematics, and medicine.

Self-funding: Many scientists supported their work using personal income—they might be university professors, teachers, writers, or engineers who used earnings from these professions to sustain scientific inquiry.

By the late 19th to early 20th century, centralized research funding led by governments and corporations began to take shape. Especially during World War I and II, national governments established research institutions and poured vast resources into defense-related research to secure military advantage.

In the United States, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and the National Research Council (NRC) were founded during WWI. In Germany, the precursor to the German Research Foundation (DFG)—the Emergency Association of German Science (Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft)—was established in 1920. Meanwhile, the rise of corporate labs like Bell Labs and GE Research marked increasing corporate involvement in funding R&D alongside government efforts.

This government- and industry-driven research funding model gradually became dominant and persists today. Governments and companies invest billions annually in global research. For instance, in 2023, U.S. federal R&D spending reached $190 billion—a 13% increase from 2022—highlighting the central role of government in advancing scientific research.

Source: ResearchHub

In the United States, the process of allocating research funds involves the federal government setting aside part of its budget for R&D, then distributing it across agencies.

Major research funding bodies include:

-

National Institutes of Health (NIH)—the world’s largest funder of biomedical research;

-

Department of Defense (DoD)—focused on defense-related research;

-

National Science Foundation (NSF)—funds research across science and engineering disciplines;

-

Department of Energy (DOE)—supports renewable energy and nuclear physics research;

-

NASA—advances aerospace and space exploration research.

B. How Centralized Funding Distorts Science

Today, university professors almost never conduct independent research without external funding from governments or corporations. This highly centralized research funding structure is one of the root causes of many problems in modern academia.

First, the application process for research funding is extremely inefficient. Despite variations between countries and institutions, the consensus globally is that the process is lengthy, opaque, and slow.

Research labs seeking grants must navigate extensive paperwork, repeated applications, and rigorous reviews, typically undergoing multiple layers of approval from government or corporate entities. Well-known, well-resourced elite labs may receive multi-million or even tens-of-millions dollar grants in one go, freeing them from constant reapplication. But this scenario is rare.

For most labs, individual grants are often only tens of thousands of dollars, forcing researchers to repeatedly apply, write voluminous documents, and endure ongoing evaluations.

Conversations with fellow graduate students reveal that many scholars and students cannot fully focus on research, as their time is consumed by grant applications and corporate projects. Worse, these industry collaborations often bear little relevance to students’ thesis work—further exposing the inefficiency and dysfunction of the current funding system.

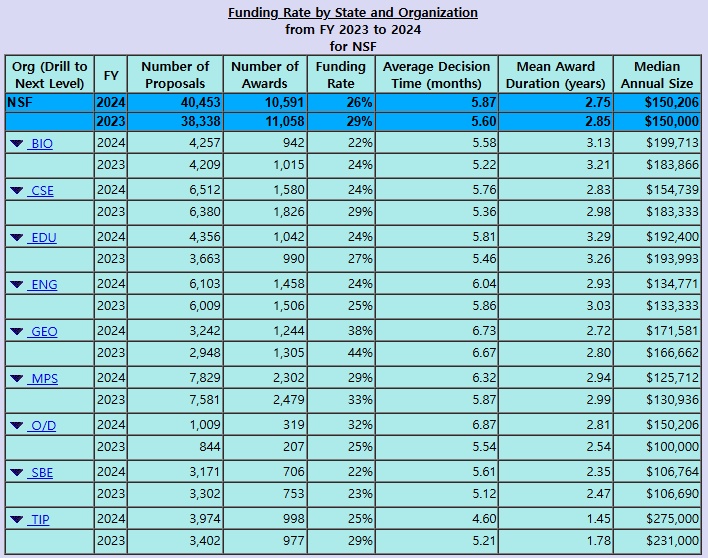

Source: NSF

Spending large amounts of time applying for funding may eventually pay off—but securing grants is far from guaranteed.

Data from the NSF shows that grant success rates in 2023 and 2024 were 29% and 26%, respectively, with median annual award sizes of just $150,000—relatively modest. NIH funding success rates typically range between 15% and 30%. Since single grants often fail to meet researchers’ needs, they must repeatedly apply for multiple projects to keep their research running.

Yet the challenges don’t end there. Personal connections play a critical role in securing funding. To improve success odds, professors often prefer collaborating with peers rather than applying alone. Moreover, informal lobbying behind closed doors to win corporate funding is not uncommon. This reliance on relationships and lack of transparency in fund allocation makes it difficult for early-career researchers to enter the field.

C. Another Major Issue with Centralized Funding: Lack of Incentives for Long-Term Research

Funding for research lasting over five years is extremely rare. According to NSF data, most research grants last 1–5 years, a pattern mirrored across other government agencies. Corporate R&D projects usually provide 1–3 years of funding, depending on the company and specific initiative.

Government funding is highly susceptible to political influence. For example, under the Trump administration, defense R&D budgets increased significantly; under Democratic leadership, environmental research tends to receive greater support. As government priorities shift with political agendas, long-term research projects become exceedingly rare.

Corporate funding faces similar limitations. In 2022, the median tenure for CEOs of S&P 500 companies was 4.8 years, with other executives having comparable tenures. Because businesses must rapidly adapt to industry and technological changes—and because executives control funding decisions—corporate-funded research projects rarely last very long.

D. Short-Termism Leads to Declining Research Quality

The centralized funding model incentivizes researchers to pursue projects that yield quick, quantifiable results. To ensure continuous funding, researchers are pressured to deliver outcomes within five years, making them favor short-term topics. This trend creates a cycle of short-termism, with very few teams or institutions willing to commit to research spanning over five years.

Additionally, the centralized funding system encourages researchers to prioritize paper quantity over quality, since short-term outputs are directly tied to grant evaluations. Scientific research can broadly be divided into incremental research (small improvements to existing knowledge) and breakthrough research (opening entirely new fields). Yet the current funding model naturally favors the former—most papers published outside top journals merely supplement prior work rather than introduce disruptive innovations.

While modern science’s high specialization inherently makes breakthrough research harder, the centralized funding system exacerbates the issue by further suppressing innovative research. This systemic bias toward incremental research undeniably becomes another barrier to revolutionary scientific progress.

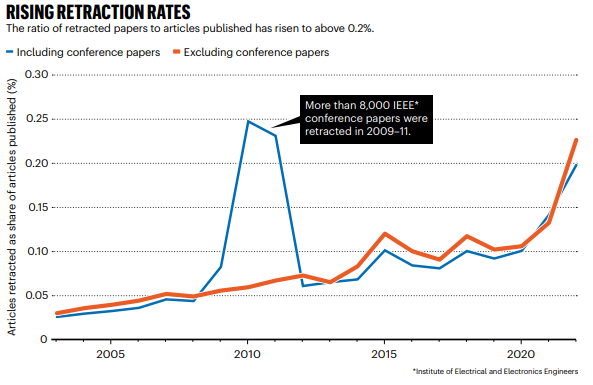

Source: Nature

Some researchers even manipulate data or exaggerate findings. The current funding mechanism demands rapid results, indirectly encouraging academic misconduct. As a graduate student, I frequently heard stories about students in other labs fabricating data. Nature reported that retraction rates for conference presentations and journal articles have sharply increased in recent years, highlighting the severity of this problem.

E. Don’t Misunderstand: Centralized Research Funding Is Unavoidable

To clarify, centralized research funding is not inherently bad. While it brings many negative side effects, it remains an indispensable pillar of modern scientific advancement.

Unlike in the past, today’s scientific research is highly complex and precise. Even a typical graduate student project can cost anywhere from several thousand to hundreds of thousands of dollars. Large-scale projects in defense, space, or fundamental physics require exponentially greater resources.

Thus, centralized funding remains necessary—but solving its resulting problems is the key challenge.

2) Systemic Challenge Two: Academic Journals

A. The Business Model of Academic Journals

In the cryptocurrency industry, Tether, Circle (stablecoin issuers), Binance, and Coinbase (centralized exchanges) dominate the market. Similarly, in academia, academic journals hold the most influential power, represented by:

-

Elsevier

-

Springer Nature

-

Wiley

-

American Chemical Society (ACS)

-

IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers)

Take Elsevier: in 2022, it generated $3.67 billion in revenue and $2.55 billion in profit, yielding a net margin of nearly 70%—higher than many tech giants. For comparison, NVIDIA’s net margin in 2024 was around 55–57%, yet academic publishers achieve even higher profitability.

Springer Nature earned $1.44 billion in revenue in the first nine months of 2024 alone, demonstrating the massive scale of the academic publishing industry.

Primary revenue sources for academic journals include:

-

Subscription fees: Accessing papers usually requires a subscription or per-article payment.

-

Article Processing Charges (APCs): Many papers sit behind paywalls, but authors can pay to make their work openly accessible (Open Access).

-

Copyright licensing and reprint sales: Upon publication, authors typically transfer copyright to the journal. Publishers profit by selling licenses to educational or commercial entities.

B. Journals: The Core of Misaligned Incentives in Academia

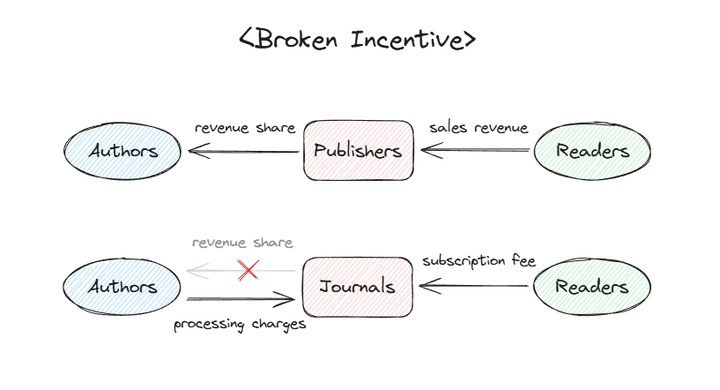

You might ask: “Why do journals dominate academia? Isn’t their business model similar to publishers in other industries?”

The answer is no. The academic journal business model is a classic case of misaligned incentives.

In traditional publishing or online platforms, publishers generally aim to maximize audience reach for creators and share in the profits. But academic journals operate in a way that benefits publishers at the expense of researchers and readers.

Although journals play an important role in disseminating scientific results, their profit model primarily enriches publishers while severely undermining the interests of researchers and readers.

If readers want to access an article, they must pay a subscription or per-article fee. But if researchers wish to publish open access, they must pay exorbitant APCs—without receiving any revenue share.

Even more unjustly, researchers not only get no share of post-publication profits, but in most cases automatically transfer copyright to the journal upon publication—meaning the publisher can monetize the content entirely on its own. This system heavily exploits researchers and is fundamentally unfair.

The academic journal business model isn’t just exploitative—it’s shockingly profitable. Take Nature Communications (one of the most prestigious fully open-access journals in natural sciences): authors must pay up to $6,790 in APCs per paper. In other words, researchers must personally finance publication in Nature Communications, a prohibitively high cost.

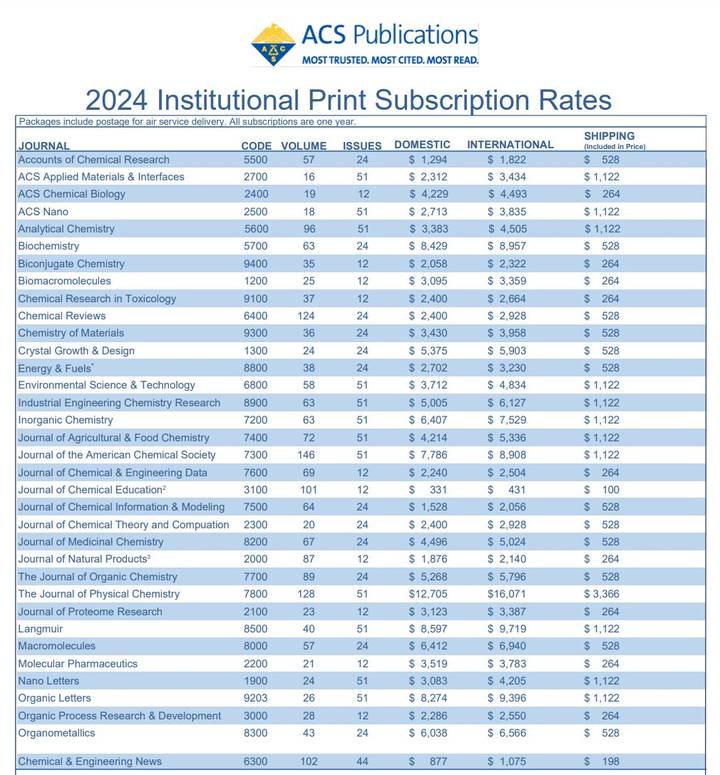

Source: ACS

Journal subscription costs are also astonishingly high. While institutional subscription fees vary by discipline and journal type, the average annual cost for a single ACS journal is $4,908. Subscribing to all ACS journals would cost an institution $170,000 annually.

For Springer Nature journals, the average annual cost per title is about $10,000, with full subscriptions reaching approximately $630,000. Given that most research institutions subscribe to multiple journals, access costs for researchers become extremely high.

C. The Biggest Problem: Researchers Are Forced to Depend on Journals, Funded Mostly by Government and Industry

More alarmingly, researchers are essentially "held hostage" by the journal system—they must publish in journals to build academic credentials, and much of the funding supporting this system comes from government or corporate research grants.

Specifically, the exploitative model works as follows:

-

Researchers must continuously publish papers to accumulate academic achievements, secure more funding, and advance their careers.

-

The research itself is funded by government or corporate grants—not out of researchers’ own pockets.

-

APCs for open-access publication are paid using research grants, not personal funds.

-

Institutional subscription fees are also largely covered by government or corporate research funding.

Since researchers mostly use external funds rather than personal money, they rarely object to these high costs. Academic publishers exploit this fact to create a highly extractive model—charging both authors and readers while monopolizing copyright.

D. Poorly Designed Peer Review Process

The problems with academic journals go beyond their profit model—their publishing workflow is also inefficient and lacks transparency. During my six years in academia, I published four papers and encountered numerous issues, particularly with the inefficient submission process and luck-dependent peer review system.

The standard peer review process at most journals includes these steps:

Researchers compile findings, write a manuscript, and submit it to a target journal.

Journal editors assess whether the paper fits the journal’s scope and basic criteria. If suitable, they assign 2–3 peer reviewers to evaluate it.

Reviewers assess the paper, provide comments and questions, and make one of four decisions:

-

Accept: Paper can be published as-is.

-

Minor Revisions: Paper mostly accepted, requiring minor edits.

-

Major Revisions: Significant revisions needed before final decision.

-

Reject: Paper declined outright.

Authors revise based on feedback, and the editor makes the final call.

While this process appears reasonable, it is riddled with inefficiencies, inconsistencies, and heavy subjectivity—potentially undermining the quality and fairness of the review system.

Problem 1: Extremely Low Review Efficiency

Though review times vary by discipline, in natural sciences and engineering, the timeline from submission to final decision is roughly:

-

Desk rejection time: 1 week – 2 months

-

Time to receive reviewer feedback: 3 weeks – 4 months

-

Time to final decision: 3 months – 1 year

If journals or reviewers delay, or if multiple review rounds are needed, the entire publication cycle can exceed one year.

For example, in my case, an editor sent my paper to three reviewers, but one didn’t respond, forcing the journal to find a replacement—adding four extra months to the review time.

Worse, if a paper undergoes lengthy review only to be rejected, researchers must resubmit elsewhere, restarting the entire process—effectively doubling the time required.

This inefficient publication process harms researchers significantly—while waiting, other teams may publish similar work, eroding the novelty of their research and negatively impacting their careers.

Problem 2: Reviewer Shortage Leads to High Randomness in Outcomes

As noted, each paper is typically reviewed by 2–3 people, and acceptance often hinges on these few individuals’ opinions.

Though reviewers are usually experts in the field, outcomes still involve an element of luck.

Here’s a personal experience:

I submitted a paper to a top-tier journal A, receiving two major revision requests and one minor revision, yet the paper was ultimately rejected.

Then I submitted it to a slightly lower-tier journal B—and the outcome was worse: one reviewer recommended rejection, another requested major revisions.

Ironically, journal B had lower academic impact than journal A, yet its review was stricter.

This reveals a core issue: paper evaluation heavily depends on a handful of reviewers’ subjective opinions, and journal editors have complete discretion over reviewer selection.

In other words, whether a paper passes depends partly on “luck”:

-

If reviewers are lenient, the paper may pass easily;

-

If reviewers are strict, the paper may be rejected outright.

In extreme cases, the same paper could be accepted by three lenient reviewers but rejected by three strict ones.

Increasing reviewer numbers to improve fairness isn’t practical—more reviewers mean higher coordination costs and longer timelines, conflicting with journal operations.

Problem 3: Lack of Incentives for Peer Review Leads to Poor Quality

The absence of incentives leads to inconsistent review quality. Experiences vary—some reviewers deeply engage with the paper and offer valuable feedback; others barely read it, raise questions already answered in the text, or give irrelevant criticisms—leading to unnecessary major revisions or outright rejection.

This is common and frustrating—many researchers feel their hard work is unjustly dismissed.

The root cause is the lack of meaningful incentives, making quality control extremely difficult.

Currently, journals invite university professors or domain experts to review. But even after investing time reading, analyzing, and writing feedback, reviewers receive no compensation.

From a professor or graduate student’s perspective, peer review is an unpaid burden. Without incentives, many treat it superficially or avoid it altogether.

Problem 4: Lack of Transparency in Peer Review Enables Bias

Peer review uses anonymity to ensure fairness—but the problem is that reviewers see author identities, while authors don’t know who reviewed them.

This information asymmetry can lead to bias:

“Favoritism”—if the author is a colleague or collaborator, reviewers may give lenient feedback, accepting mediocre papers.

“Sabotage”—if the author belongs to a competing team, reviewers might intentionally give negative reviews or delay the process, preventing competitors from publishing first.

This kind of “backroom manipulation” in academia is far more common than people realize.

E. The Illusion of Impact Factor

The final core issue with the journal system is citation count.

How do we evaluate a researcher’s academic achievement and expertise? Researchers excel in different ways:

-

Some are skilled in experimental design,

-

Others are good at identifying promising research directions,

-

And some excel at uncovering overlooked details.

But qualitatively assessing every researcher comprehensively is nearly impossible. Thus, academia relies heavily on quantitative metrics—simple numbers to measure academic impact, mainly citation counts and H-index.

In academia, researchers with higher H-index and citation counts are generally considered more successful.

The H-index measures a researcher’s academic output and influence. For example:

An H-index of 10 means the researcher has at least 10 papers, each cited at least 10 times.

Though H-index is a common metric, ultimately, citation count remains the most important benchmark.

So how can researchers boost citation counts?

Besides publishing high-quality papers, choosing the right research direction is crucial. The popularity of a research field and the number of researchers involved affect citation volume—the more researchers, the higher the chance of citations, naturally boosting citation counts.

Source: Clarivate

The table above shows Clarivate’s 2024 Journal Impact Factor (IF) rankings. IF represents the average number of annual citations per paper in a journal. For example, a journal with an IF of 10 sees its papers cited 10 times per year on average.

Observing the rankings reveals that high-impact-factor journals are concentrated in specific fields like cancer, medicine, materials, energy, and machine learning. Even within broader disciplines like chemistry, subfields like batteries and clean energy tend to have higher citation rates than traditional organic chemistry.

This suggests that over-reliance on citation counts as the main evaluation criterion may push researchers toward popular fields, reducing research diversity.

Moreover, it shows that citation counts and impact factors aren’t universal measures of researcher or journal quality. For example, among ACS journals:

ACS Energy Letters has an IF of 19, while JACS has an IF of only 14.4—yet JACS has long been regarded as one of the most authoritative journals in chemistry.

Nature is often seen as the ideal publication venue, with an IF of 50.5. But its sub-journal Nature Medicine, focused on medicine, has an IF of 58.7.

F. Publish or Perish

Success arises from failure. Progress in any field requires failure as a stepping stone. Today’s published research results are typically built upon countless experiments and failed attempts.

Yet in modern science, almost all papers report only “successful” results—failed attempts en route to success are rarely published, often ignored altogether.

In the fiercely competitive academic environment, researchers have little incentive to report failed experiments, as it doesn’t help their careers and may even be seen as wasted time.

3) Systemic Challenge Three: Collaboration

In software development, open-source projects have revolutionized coding—making code publicly accessible and encouraging global developers to contribute, leading to more efficient collaboration and better software products.

Yet science has followed the opposite trajectory.

Letter from Isaac Newton to Robert Hooke

In the 17th century and earlier periods of scientific development, scientists grounded in “natural philosophy” prioritized knowledge sharing, exhibiting openness and cooperation while distancing themselves from rigid authority. For example, despite academic rivalry, Isaac Newton and Robert Hooke exchanged letters discussing their findings, critiquing each other’s work, and jointly advancing science.

In contrast, modern scientific environments are far more closed. Researchers compete fiercely for funding and strive to publish in high-impact-factor journals. Unpublished research is strictly confidential, with strong restrictions on external sharing. Labs in the same field often view each other as competitors, lacking channels to learn about each other’s progress.

Since most research builds incrementally on prior work, different labs are likely to study similar topics simultaneously. Without shared research processes, identical studies often run in parallel across multiple labs. This is extremely inefficient and fosters a **winner-takes-all** academic culture—the lab that publishes first receives all recognition.

Researchers often face this situation: just as they’re about to finish, another lab publishes similar work, rendering their efforts worthless.

In the worst cases, even researchers within the same lab may hide data or findings from each other, creating internal competition instead of collaborative synergy.

Today, open-source culture is foundational in computer science. Modern science also needs to shift toward a more open, cooperative culture to better serve the public good.

3. How to Fix Traditional Science (TradSci)?

1) Many Have Tried to Improve It

Researchers in academia are well aware of the current system’s flaws. Yet despite their visibility, these are deeply entrenched structural issues that individuals cannot easily fix. Still, over the years, many initiatives have been launched to improve the status quo.

A. Fixing Centralized Research Funding

Fast Grants: During the COVID-19 pandemic, Stripe CEO Patrick Collison noticed the inefficiency of traditional research funding and launched Fast Grants, raising $50 million to fund hundreds of research projects. The program made funding decisions within 14 days, with awards ranging from $10,000 to $500,000, providing substantial support to researchers.

Renaissance Philanthropy: Founded by Tom Kalil, who previously advised the Clinton and Obama administrations on tech policy. This nonprofit consultancy connects funders with high-impact science and technology projects. Funded by Eric and Wendy Schmidt, its model resembles the historical patronage system once relied upon by European scientists.

HHMI (Howard Hughes Medical Institute): Unlike traditional project-based funding, HHMI uses a unique model that directly supports individual researchers rather than specific projects. This long-term funding reduces pressure for short-term results, allowing researchers to focus on sustained scientific exploration.

experiment.com: An online crowdfunding platform allowing researchers to present their work to the public and raise necessary funds from individual donors—offering a decentralized alternative to traditional research funding.

B. Improving Academic Journals

PLOS ONE: An open-access scientific journal where anyone can freely read, download, and share papers. It evaluates submissions based on scientific validity rather than perceived impact and accepts negative, inconclusive, or null results—earning high regard in academia. Its streamlined publication process allows faster dissemination of results. However, it charges researchers $1,000–$5,000 in APCs—a significant barrier.

arXiv, bioRxiv, medRxiv, PsyArXiv, SocArXiv: These preprint servers allow researchers to share draft manuscripts before formal publication—enabling rapid dissemination, establishing priority, and facilitating community feedback and collaboration. They are free to access, greatly lowering barriers to academic knowledge.

Sci-Hub: Created by Kazakh programmer Alexandra Asanovna Elbakyan, Sci-Hub aims to bypass journal paywalls to provide free access to papers. Though illegal in most jurisdictions and repeatedly sued by publishers like Elsevier, it is praised for advancing open access while criticized for violating copyright laws.

C. Enhancing Academic Collaboration

ResearchGate: A professional social network for researchers offering paper sharing, Q&A, and collaboration opportunities—promoting global academic exchange.

CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research): A nonprofit organization in particle physics that coordinates large-scale experiments beyond individual labs’ capabilities. It brings together researchers from multiple countries, funded according to GDP contributions—creating an international, collaborative research model.

2) DeSci: A New Wave of Change

Although previous efforts have made some progress in addressing modern science’s challenges, none have delivered transformative disruption to the academic system.

In recent years, with the rise of blockchain technology, a new concept called Decentralized Science (DeSci) has gained attention—as a potential solution to these structural issues.

But what exactly is DeSci? Can it truly reshape the modern scientific system?

4. DeSci Arrives

1) Overview of DeSci

DeSci (Decentralized Science) aims to turn scientific knowledge into a public resource, building a more efficient, fair, transparent, and open scientific system by improving research funding, workflows, peer review, and knowledge-sharing mechanisms.

Blockchain technology plays a central role in achieving this goal, with key features including:

-

Transparency: Except for privacy chains, blockchains are inherently public and transparent—anyone can view transactions. This enhances transparency in funding and peer review, reducing backroom manipulation and unfair practices.

-

Ownership: Blockchain assets are protected by private keys, enabling researchers to easily assert data ownership, monetize research outputs, or establish intellectual property (IP) rights.

-

Incentive Mechanisms: Incentives are core to blockchain networks. Token rewards can motivate researchers to actively participate in research, peer review, and data sharing, increasing collaboration.

-

Smart Contracts: Running on decentralized networks, smart contracts automatically execute predefined actions as coded. This enables transparent, impartial management of research collaboration and automatic execution of funding, data sharing, and reward logic.

2) Potential Applications of DeSci

As the name suggests, DeSci can be applied across multiple areas of scientific research. ResearchHub categorizes DeSci’s potential applications into five domains:

Research DAOs: These decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) focus on specific research topics and use blockchain to transparently manage research planning, funding distribution, governance voting, and project operations.

Publishing: Blockchain can decentralize academic publishing, transforming the traditional model. Research papers, data, and code can be permanently stored on-chain, ensuring credibility, enabling free access for all, and using token incentives to improve peer review quality and transparency.

Funding & IP: Researchers can easily raise global research funding via blockchain networks. Research projects can be tokenized, allowing token holders to participate in decision-making and potentially share future IP revenues.

Data: Blockchain provides secure, transparent storage and management, supporting data sharing and verification—reducing academic fraud and data tampering.

Infrastructure: Tools for governance, storage, community platforms, and identity systems can be integrated into DeSci projects to support the growth of a decentralized research ecosystem.

To truly understand DeSci, the best approach is to study specific projects within the DeSci ecosystem—seeing how they tackle structural issues in modern science. Next, we’ll examine representative DeSci projects.

5. The DeSci Ecosystem

Source: ResearchHub

1) Why Ethereum Is Best Suited for DeSci

Unlike sectors like DeFi, gaming, or AI, DeSci projects are primarily concentrated in the Ethereum ecosystem. Key reasons include:

Credible Neutrality: Among all smart contract platforms, Ethereum is the most neutral network. DeSci involves large financial flows (e.g., research funding), so decentralization, fairness, censorship resistance, and trustworthiness are crucial—making Ethereum the optimal choice for DeSci projects.

Network Effects: Ethereum has the largest user base and liquidity among smart contract networks. Compared to other sectors, DeSci is still niche. If projects were spread across multiple chains, liquidity and ecosystem fragmentation would hinder growth. Thus, most DeSci projects choose Ethereum to leverage its strong network effects.

DeSci Infrastructure: Few DeSci projects build entirely from scratch—most use existing infrastructure (like Molecule) to accelerate development. Since most DeSci tools are currently Ethereum-based, the ecosystem naturally centers on Ethereum.

For these reasons, the DeSci projects discussed here belong primarily to the Ethereum ecosystem. Next, we’ll dive into representative DeSci projects.

2) Funding & Intellectual Property (IP)

A. Molecule

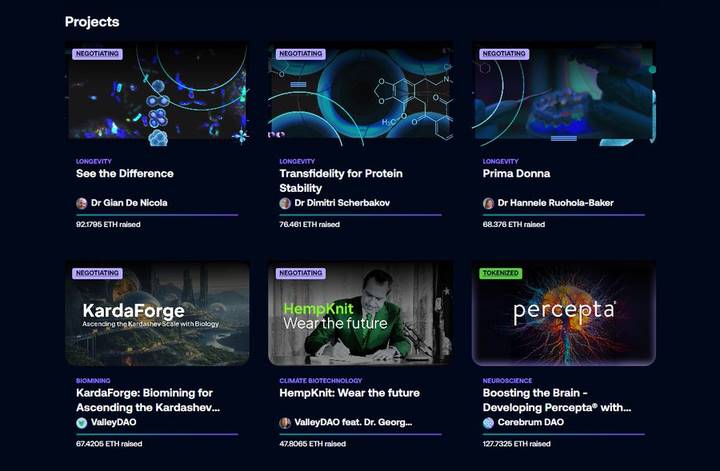

Source: Molecule

Molecule is a platform for funding and tokenizing biopharmaceutical intellectual property (IP). Researchers can raise funds from many individuals via blockchain, tokenize research IP, and distribute IP Tokens to funders based on contribution size.

Catalyst is Molecule’s decentralized research funding platform connecting researchers and funders.

Researchers prepare documentation and project plans, then submit proposals on Catalyst.

Funders review proposals, select projects to support, and provide ETH as funding.

Once funding is complete, the platform issues an IP-NFT (Intellectual Property NFT) and IP Tokens—funders claim corresponding IP Tokens based on their contribution.

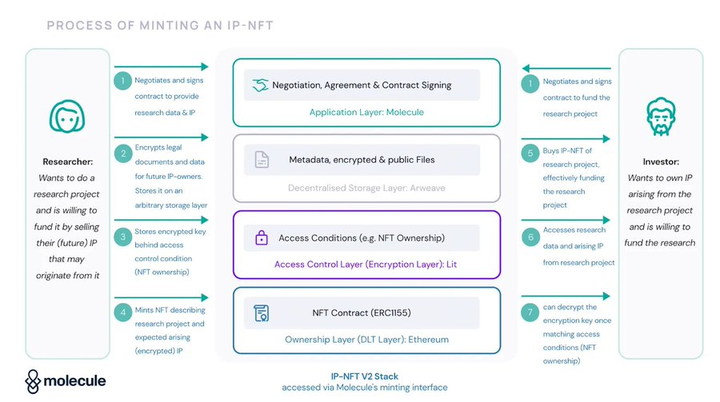

Source: Molecule

The IP-NFT is the on-chain tokenized version of a research project’s IP, embedding two legal agreements into a smart contract.

The first agreement is the Research Agreement, signed between researchers and funders. It covers research scope, deliverables, timelines, budget, confidentiality, IP and data ownership, publication, result disclosure, licensing, and patent terms.

The second is the Assignment Agreement, ensuring that rights under the Research Agreement transfer with the IP-NFT—so the rights of the current holder pass to any new owner.

IP Tokens represent partial governance rights over the research project’s IP.

Token holders can participate in key research decisions and access exclusive research information.

IP Tokens don’t guarantee direct revenue from research outcomes, but future commercial profits may be distributed to IP Token holders at the IP holder’s discretion.

Source: Molecule

IP Token prices are determined by the Catalyst Bonding Curve, which reflects the relationship between token supply and price. As more tokens are issued, prices rise—motivating early funders to acquire IP Tokens at lower costs, enhancing the appeal of research funding.

Examples of successful research funding via Molecule:

Fang Laboratory at the University of Oslo: Focused on aging and Alzheimer’s research, the lab received funding through VitaDAO using Molecule’s IP-NFT framework to identify and characterize new mitochondrial autophagy activators—significant for Alzheimer’s research.

Artan Bio: Focused on tRNA research, Artan Bio received $91,300 in research funding from the VitaDAO community via Molecule’s IP-NFT framework.

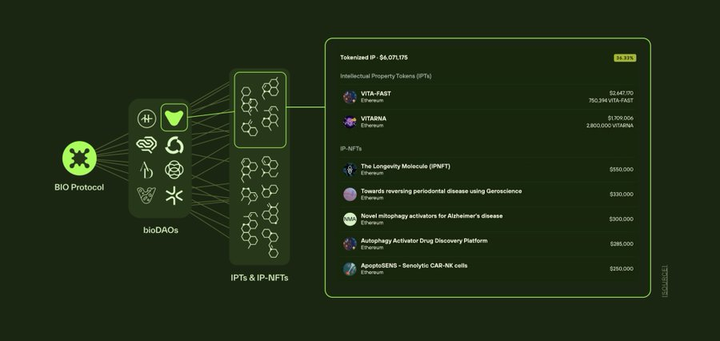

B. Bio.xyz

Source: Bio.xyz

Bio.xyz is a curation and liquidity protocol in the DeSci space—similar to an incubator for BioDAOs. Its goals include:

-

Curate, create, and accelerate new BioDAOs in funding research on-chain.

-

Provide long-term funding and liquidity for BioDAOs and on-chain biotech assets.

-

Standardize frameworks, tokenomics, and data/product systems for BioDAOs.

-

Promote generation and commercialization of scientific IP and research data.

BIO Token holders vote on which new BioDAOs join the ecosystem. When a BioDAO is approved, BIO holders who voted for it can participate in initial token auctions—similar to whitelist seed rounds.

Approved BioDAO governance tokens (e.g., VITA) are paired with BIO and added to liquidity pools—solving liquidity issues for BioDAOs (e.g., VITA/BIO trading pair). Additionally, Bio.xyz runs the bio/acc rewards program, offering BIO Token rewards to BioDAOs completing key milestones.

Furthermore, the BIO Token serves as a meta-governance token across multiple BioDAOs—BIO holders can participate in governance of several BioDAOs. Bio.xyz also provides $100,000 in funding to incubated BioDAOs in exchange for 6.9% of their token supply—increasing protocol-managed assets (AUM) and enhancing BIO Token value.

Bio.xyz uses Molecule’s IP-NFT and IP Token framework for IP management. For example, VitaDAO has successfully issued IP Tokens (VitaRNA and VITA-FAST) within the Bio ecosystem.

Current BioDAOs being incubated by Bio.xyz include:

-

Cerebrum DAO: Focused on preventing neurodegenerative diseases.

-

PsyDAO: Dedicated to advancing consciousness through safe, accessible psychedelic experiences.

-

cryoDAO: Advancing cryopreservation research.

-

AthenaDAO: Promoting women’s health research.

-

ValleyDAO: Supporting synthetic biology research.

-

HairDAO: Collaborating on hair loss treatments.

-

VitaDAO: Focused on human longevity research.

C. Summary

Bio.xyz curates BioDAOs, providing tokenomic frameworks, liquidity services, funding, and incubation support. When IP within the Bio ecosystem is successfully commercialized, Bio.xyz’s treasury grows—creating a virtuous cycle.

3) Research DAOs

A. VitaDAO

Among research DAOs, VitaDAO is undoubtedly one of the most prominent. It gained attention not only as an early DeSci project but also for receiving a lead investment from Pfizer Ventures in 2023.

VitaDAO focuses on longevity and aging research, having funded over 24 projects and disbursed over $4.2 million in funding. In return, VitaDAO acquires IP-NFTs or equity in related companies via Molecule.xyz’s IP-NFT framework.

VitaDAO fully leverages blockchain transparency—its treasury is publicly viewable, currently valued at around $44 million, including approximately $2.3 million in equity and $29 million in tokenized IP assets. VITA Token holders participate in governance votes shaping the DAO’s direction and gain access to certain healthcare services.

The most notable projects funded by VitaDAO are VitaRNA and VITA-FAST—both tokenized and actively traded:

-

VitaRNA market cap: ~$13 million

-

VITA-FAST market cap: ~$24 million

Both regularly host meetings with the VitaDAO community to update on research progress.

Representative Research Projects

VitaRNA

An IP Token project led by biotech firm Artan Bio.

Received VitaDAO funding in June 2023, issued IP-NFT and split into IP Tokens in January 2024.

Focus: Suppressing arginine nonsense mutations, particularly the CGA codon, which is crucial in DNA repair, neurodegenerative diseases, and tumor suppression proteins.

VITA-FAST

An IP Token project led by Viktor Korolchuk’s lab at Newcastle University.

Focus: Discovering new autophagy activators.

Autophagy is a cellular process whose decline is considered a key factor in biological aging. VITA-FAST aims to explore anti-aging and disease treatment strategies by activating autophagy, ultimately extending human healthspan.

B. HairDAO

HairDAO is an open-source R&D network where patients and researchers collaborate on hair loss treatments.

According to Scandinavian Biolabs, hair loss affects 85% of men and 50% of women over their lifetimes. Yet available treatments remain extremely limited: only Minoxidil, Finasteride, and Dutasteride. Notably, Minoxidil was FDA-approved in 1988, Finasteride in 1997.

Even so, these approved treatments only slow or temporarily halt hair loss—they cannot cure it. Development of new therapies is slow due to:

-

Complex etiology: Hair loss results from genetics, hormonal changes, immune responses, and more—making targeted therapy extremely challenging.

-

High R&D costs: Developing new drugs requires massive investment and time. But since hair loss isn’t life-threatening, it ranks low in funding priority—limiting progress.

HairDAO promotes research through decentralized incentives:

-

Patients sharing treatment experiences and data on the HairDAO app earn HAIR governance tokens as rewards.

-

HAIR Token holders vote on research funding directions.

-

HAIR Token holders receive discounts on HairDAO-branded shampoo products.

-

Staking HAIR Tokens grants faster access to confidential research data.

C. Other Research DAOs

CryoDAO

-

Focused on cryopreservation research.

-

Treasury exceeds $7 million, having funded 5 research projects.

-

CRYO Token holders participate in governance and gain early or exclusive access to breakthroughs and data.

ValleyDAO

-

Aims to tackle climate challenges by funding synthetic biology research.

-

Synthetic biology uses organisms to sustainably produce nutrients, fuels, and medicines—seen as key to combating climate change.

-

Has funded multiple projects, including research by Professor Rodrigo Ledesma-Amaro at Imperial College London.

CerebrumDAO

-

Focused on brain health research, especially Alzheimer’s prevention.

-

Its Snapshot page displays multiple research proposals seeking funding.

-

Governance is decentralized—all funding decisions are made by DAO member votes.

4) Publishing

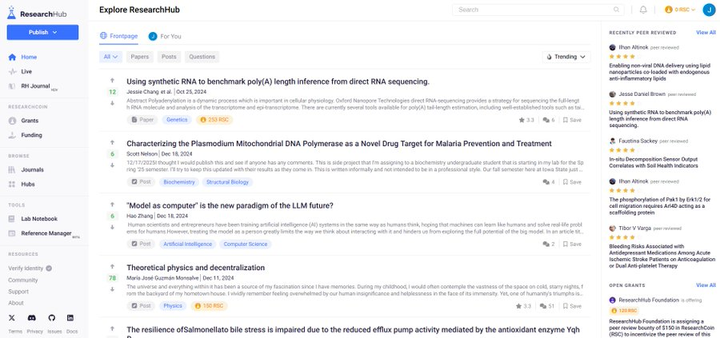

A. ResearchHub

Source: ResearchHub

ResearchHub is currently the leading academic publishing platform in the DeSci space, aiming to become the “GitHub of science.” Founded by Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong and Patrick Joyce, it raised $5 million in a Series A round in June 2023, led by Open Source Software Capital.

ResearchHub offers open research publishing and discussion tools, using RSC (ResearchCoin) tokens to incentivize paper publication, peer review, and content curation.

Core features include:

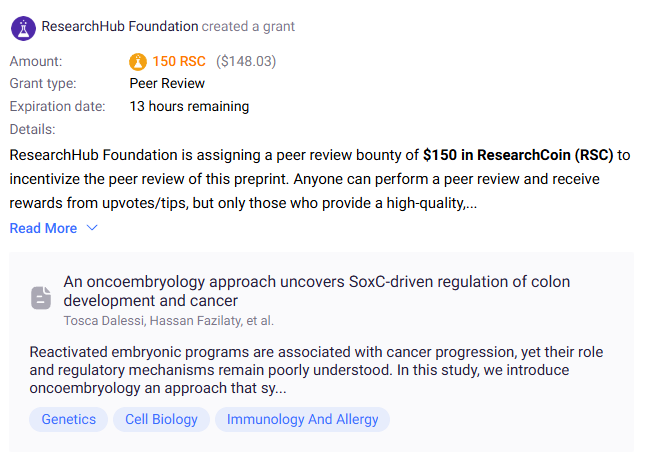

Funding

Source: ResearchHub

Users can create bounties using RSC tokens, requesting other ResearchHub users to complete specific tasks. Main bounty types include:

Peer Review: Requesting manuscript reviews.

Answer to Question: Seeking answers to specific questions.

Funding.

Source: ResearchHub

Under the Funding tab, researchers can upload proposals and receive RSC token support from users.

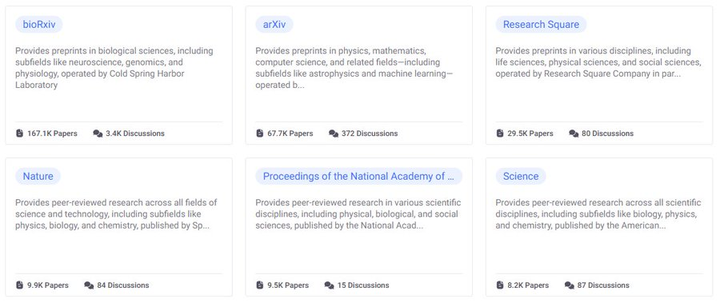

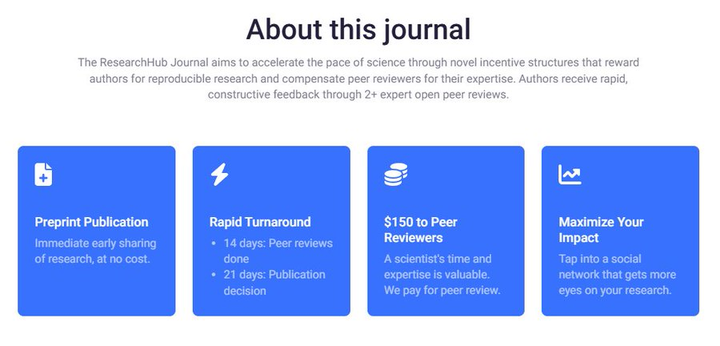

①. Journals

Source: ResearchHub

The Journals section archives papers from peer-reviewed journals and preprint servers. Users can browse literature and participate in discussions. However, many peer-reviewed papers are behind paywalls—users often only see summaries written by others.

②. Hubs

Source: ResearchHub

Hubs archive preprints categorized by discipline. All papers here are open access—anyone can read full content and join discussions.

③. Lab Notebook

The Lab Notebook is an online collaborative workspace allowing multiple users to co-write papers. Similar to Google Docs or Notion, it integrates seamlessly with ResearchHub and enables direct publishing.

④. RH Journal

Source: ResearchHub

RH Journal is ResearchHub’s own academic journal. It features an efficient peer review process—reviews completed in 14 days, final decisions in 21 days. It also introduces peer review incentives to address misaligned incentives in traditional systems.

RSC Token

Source: ResearchHub

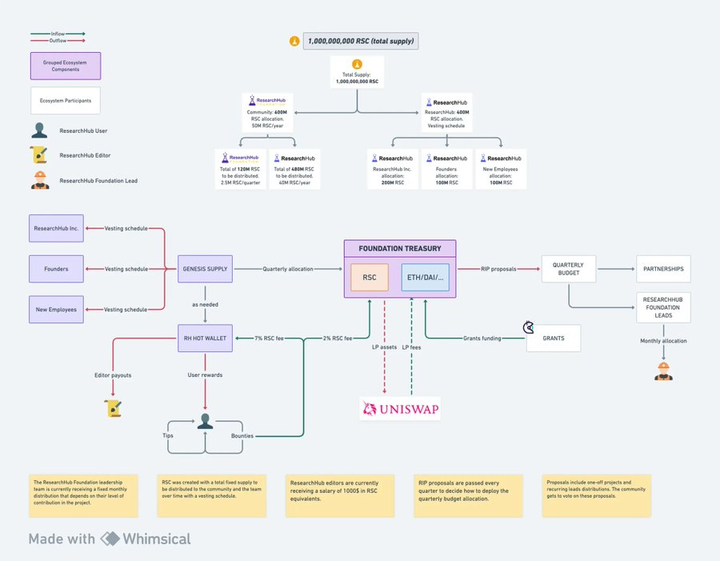

The RSC Token is an ERC-20 token in the ResearchHub ecosystem with a total supply of 1 billion. It aims to encourage user participation and support ResearchHub’s evolution into a fully decentralized open platform.

Main uses of RSC Token include:

-

Governance voting

-

Tipping other users

-

Bounty programs

-

Incentives for peer reviewers

-

Rewards for curating research papers

B. ScieNFT

ScieNFT is a decentralized preprint server allowing researchers to publish research as NFTs. Content isn’t limited to papers—it can include images, research ideas, datasets, artworks, methods, and even negative experimental results.

ScieNFT uses decentralized storage—preprint data is stored on IPFS and Filecoin, while NFT assets are uploaded to the Avalanche C-Chain.

While using NFTs to track provenance and attribution of research is advantageous, ScieNFT faces challenges:

-

The actual value and utility of buying these NFTs remain unclear.

-

Lack of effective curation mechanisms impacts content quality management.

C. deScier

Source: deScier

D. deScier

deScier is a decentralized scientific journal platform. Like traditional publishers such as Elsevier or Springer Nature, deScier hosts multiple journals.

On deScier, 100% of paper copyrights belong to researchers, and peer review remains mandatory.

However, the platform faces major issues:

-

Few papers published.

-

Slow upload speed affects content update frequency.

5) Data

A. Data Lake

Data Lake’s software enables researchers to integrate multiple participant recruitment channels, track effectiveness, manage data usage consent, and conduct prescreening surveys—while ensuring users retain control over their data.

The platform allows researchers to share and easily manage patient data usage consent, enabling third parties to access data compliantly.

Data Lake uses Data Lake Chain—a Layer 3 network based on Arbitrum Orbit—specifically designed to manage patient data usage consent.

B. Welshare Health

Source: Welshare Health

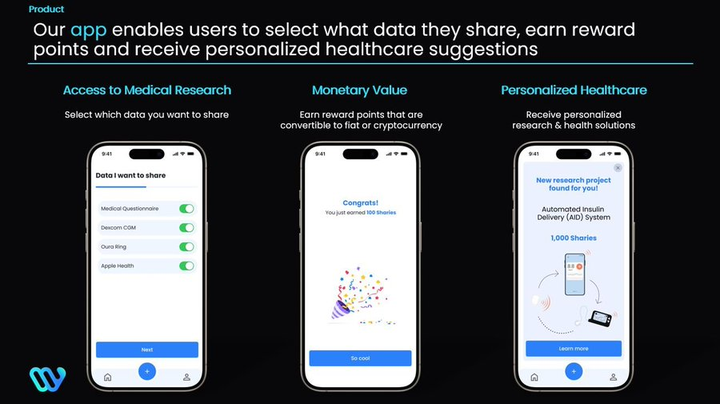

In traditional medical research, one of the biggest bottlenecks is slow clinical trial recruitment and insufficient patient numbers. Additionally, while patient medical data is highly valuable, it carries risks of misuse. Welshare aims to solve these issues using Web3 technology.

Patients can securely manage personal medical data, monetize it for income, and receive personalized healthcare services.

Medical researchers gain easier access to diverse datasets, accelerating medical research.

Welshare offers a Base Network-based app allowing users to selectively share data to earn in-app reward points, redeemable for cryptocurrency or fiat currency.

C. Hippocrat

Hippocrat is a decentralized medical data protocol allowing individuals to securely manage health data using blockchain and zero-knowledge proof (ZKP) technology.

Its first product, HippoDoc, is a telemedicine app combining medical databases, AI technology, and professional healthcare support to provide patient consultations.

Throughout the consultation, patient data is securely stored on the blockchain, ensuring privacy and data security.

6) DeSci Infrastructure

A. Ceramic

Ceramic is a decentralized event streaming protocol. Developers can use it to build decentralized databases, distributed computing pipelines, and authenticated data streams. Due to its properties, Ceramic is highly suitable for DeSci projects, functioning as a decentralized database:

-

Data on the Ceramic network is permissionless—researchers can share and collaborate efficiently.

-

Actions like paper publication, citation, and peer review are represented as “Ceramic Streams” on the network—each stream modifiable only by its creator, ensuring IP provenance.

-

Ceramic also provides verifiable claims infrastructure, allowing DeSci projects to adopt its reputation system and enhance research trust.

B. bloXberg

bloXberg is a blockchain infrastructure dedicated to research, initiated by the Max Planck Digital Library in Germany, with partner institutions including ETH Zurich, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, and IT University of Copenhagen.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News