Why Did Binance Invest in BIO Protocol? Understanding the New DeSci Narrative

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Why Did Binance Invest in BIO Protocol? Understanding the New DeSci Narrative

This article helps you understand why Binance invested in BIO Protocol, exploring changes in scientific research funding, the structure of existing scientific research institutions, and how Web3 technology—specifically the current DeSci narrative—can transform the funding and organization of scientific research.

Original authors: Elliot Hershberg and Jocelynn Pearl

Translated by: LlamaC

(Portfolio: Burning Man 2016, about Tomo: eth Foundation illustrator)

(Portfolio: Burning Man 2016, about Tomo: eth Foundation illustrator)

「Recommended note: This article helps you understand why Binance invested in BIO Protocol, exploring changes in scientific research funding, the structure of existing research institutions, and how Web3 technologies—specifically the current DeSci narrative—are transforming the way science is funded and organized.」

Main Text👇

Science is a foundational tool for human progress.

It is a system we've built to arrive at detailed explanations of objective reality that are hard to change. These types of explanations require coherent models capable of accounting for empirical observations. The only way to achieve such explanations is through challenging experiments and theoretical work ensuring every detail functions properly and remains tightly linked to objective reality. This kind of explanatory power lies at the heart of our transition from myth to physics, from caves to skyscrapers. Physicist David Deutsch argues this is the core idea behind the scientific revolution: "Ever since, our knowledge of the physical world and how to adapt it to our desires has been continually growing."

The guiding light of scientific discovery is one of our most valuable resources, which must be carefully managed. Beyond developing new explanations, we’ve also built a complex human system that transforms new knowledge into inventions powering the modern world. Researching and improving this system is crucial—and requires interacting with countless other complex human systems. As visionary Vannevar Bush argued, "We need legislators, courts, and the public to better understand this entire complex matter. Inventions will not be lacking; real inventors simply can’t help but invent. But we want more successful inventions, and to get them, we need deeper understanding."

Guided by the mission of accelerating scientific progress, Vannevar Bush led efforts to expand the U.S. research funding system to its present scale. This powerful system is what scientist and former head of the Office of Science and Technology Policy Eric Lander calls the "miracle machine."

Miracle Machine; created using Midjourney

Miracle Machine; created using Midjourney

Our systematic efforts to fund basic science have ultimately led to miracles such as the internet, artificial intelligence, cancer immunotherapies, and CRISPR gene-editing technology. While the results so far have been miraculous, this machine does not run on its own: maintaining the system is absolutely critical.

Yet over time, we have grown complacent in maintaining this machine.

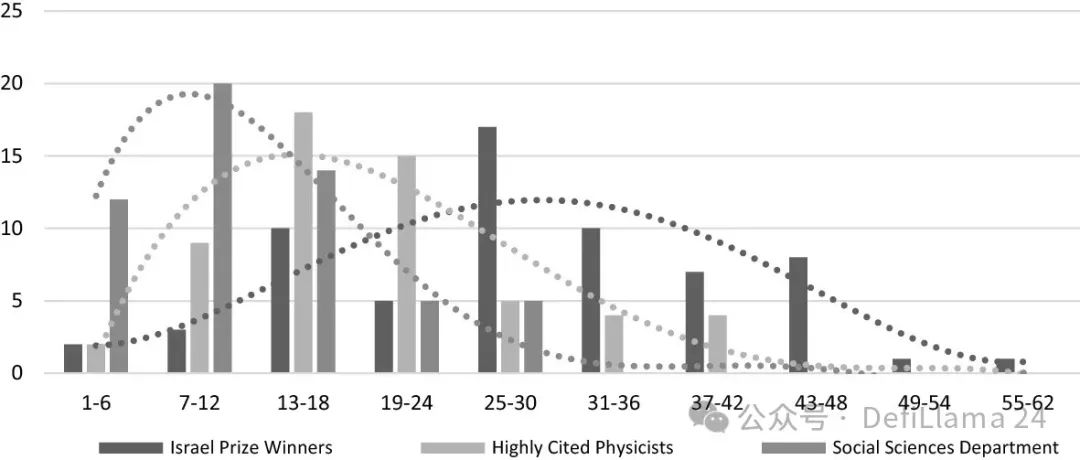

Lander coined this term passionately advocating for increased federal research budgets, while in reality, research funding has declined in recent years. Over time, “adjusted for inflation, the budget of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the primary federal agency for medical research, has dropped nearly 25% since 2003.” The challenges of funding science go beyond merely advocating for larger budgets. Our actual funding mechanisms have become increasingly rigid, inefficient, and consensus-driven. One U.S. government study estimates professors now “spend about 40% of their research time navigating bureaucratic labyrinths,” necessary to secure funding for their labs. In another alarming survey, 78% of researchers said they would “significantly” change their research plans if given unrestricted funds. Young scientists also face severe bottlenecks in securing early-career funding, despite this potentially being the most productive and breakthrough-prone period of their lives.

Yair & Goldstein, 2019. Figure 2 Distribution of the age at career peak (or highest publication year) across three small studies

Yair & Goldstein, 2019. Figure 2 Distribution of the age at career peak (or highest publication year) across three small studies

Beyond laboratory funding, there are serious structural bottlenecks in translating scientific discoveries into new drugs and products. This is what former NIH Director Elias Zerhouni called the “valley of death.” In recent years, the pace of biotech company formation has slowed. Physician-scientist Eric Topol recently pointed out that despite profound advances in understanding the human genome, this knowledge has yet to translate into practical clinical applications.

Any optimist and advocate for human progress should regard the health and efficiency of our “miracle machine” as critically important—and clearly, we are far from reaching our full potential.

So what should we do?

Challenges and inefficiencies represent new opportunities. In recent years, innovation in research funding mechanisms has exploded. Metascience—the study of science itself—has become an applied discipline. Will the next miracle machine be a modernized version of our current system, or something entirely new? Where and how will the next wave of scientific progress occur? These are central questions to almost every type of innovation. As R. Buckminster Fuller put it: "You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete."

When analyzing complex human systems with multiple layers of incentives, following the money is often an unexpectedly good strategy.

All the President's Men | Follow The Money Scene | Warner Bros. Entertainment

https://youtu.be/QodGxD19_as

Our goal here is to better understand how we currently fuel the miracle machine. How do we actually fund scientific innovation and commercialization? From there, we’ll examine ideas, technologies, and projects aiming to transform this process.

Let’s dive into some recent innovations in research funding—from private capital to cryptocurrency, to building entirely new research-focused institutions targeting uncharted territories in scientific knowledge.

We’ll explore:

- A macro view of current scientific funding

- Killer Web3 use cases

- Faster Gas, faster funding

- Going full Bucky (building from scratch)

A Macro View of Current Scientific Funding

How is the current miracle machine actually structured?

Almost all scientific disciplines broadly fall into three types of organizations:

- Academic institutions (universities, nonprofit institutes, etc.)

- Startups

- Corporations (established companies with R&D labs)

Let’s make this concrete by observing how biomedical research works. The National Institutes of Health (NIH), with an annual budget of around $45 billion, is the primary source of biomedical research funding. Other agencies like the National Science Foundation, with an annual budget of about $8 billion, are also major funders. These large government bodies distribute funds via various grant mechanisms to principal investigators (PIs) who apply for support. PIs are typically professors at research universities or medical schools, responsible for managing laboratories. Actual research is conducted by graduate students, temporary postdoctoral researchers (postdocs), and some professionals, while PIs serve in managerial roles.

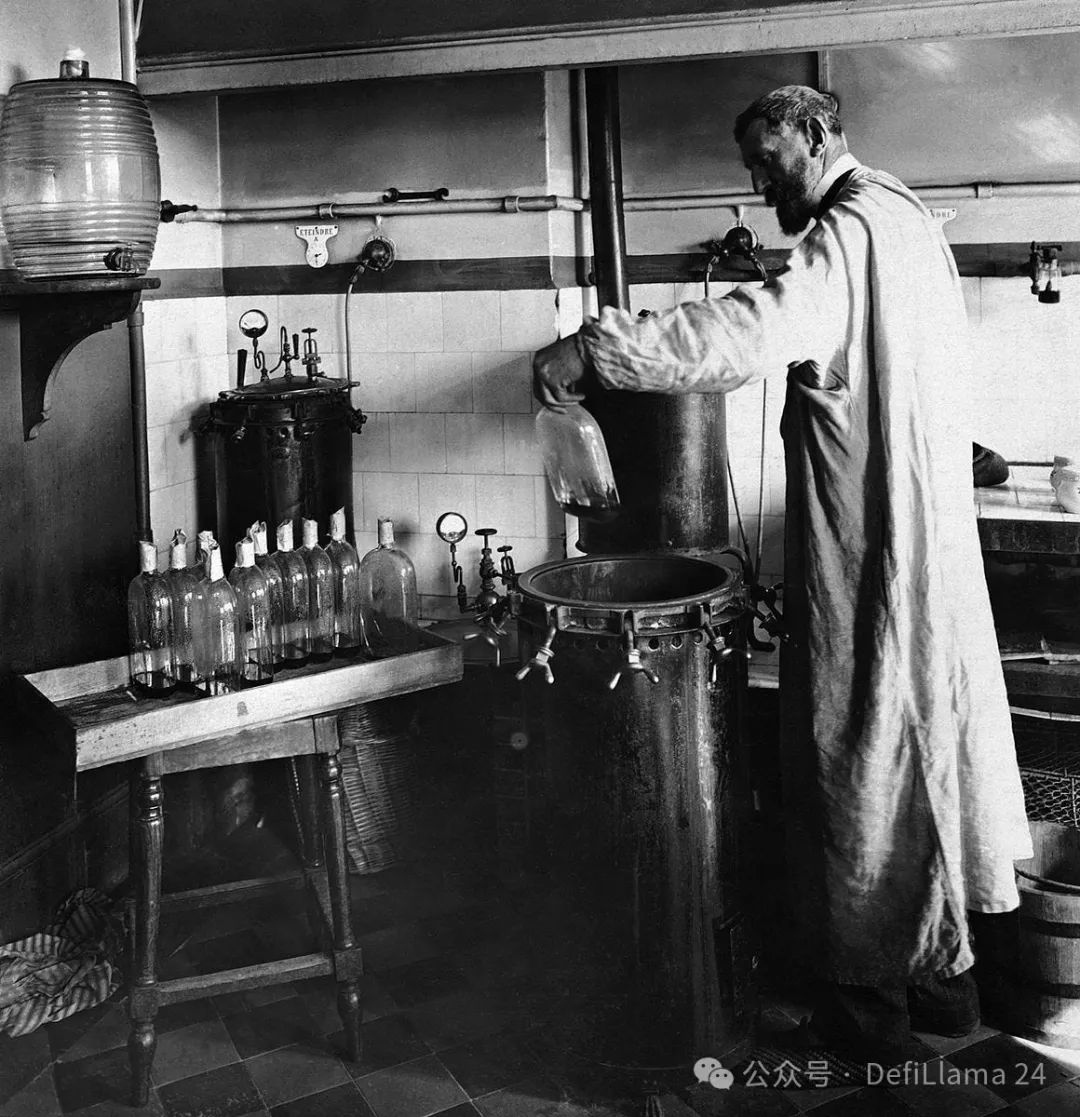

This hierarchical funding and organizational structure isn't the only way we could conduct laboratory-based scientific research. The distinguished chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur (after whom pasteurization is named) personally performed many experiments with the help of lab assistants (as noted above). This was actually a key part of his research process: he trained himself to maintain a “prepared mind” to notice even subtle experimental outcomes. Today, “when the PI enters the lab, beware” has become a common joke, as their experimental skills have largely atrophied.

Emily Noël broke lab equipment during a procedure due to excessive force.

https://x.com/noelresearchlab/status/1171376608437047296

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when the shift to the modern lab system occurred, but World War II was a pivotal turning point. Given the Manhattan Project’s importance to the war effort, scientific funding underwent a significant transformation: it was no longer just about supporting the pursuit of knowledge—scientific funding now had direct implications for national security and economic growth. These ideas were best crystallized in Vannevar Bush’s 1945 report, Science—The Endless Frontier.

In the years that followed, many of today’s scientific and biomedical research institutions came into being. Since WWII, the number of U.S. medical schools has doubled. Between 1945 and 1965, faculty positions increased by 400%. Science was no longer a solitary intellectual pursuit but increasingly became a team endeavor funded by government grants. This is often referred to as the growing “bureaucratization” of science.

Thus, the first major gear of the miracle machine is government-funded research laboratories.

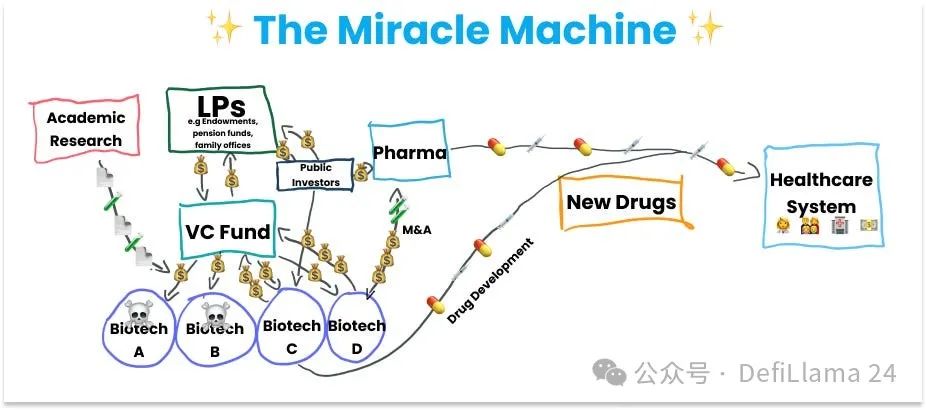

These labs are responsible for building foundational explanations of the world, making translation possible. Commercialization of science occurs through spin-off companies formed around specific intellectual property (IP) with translational potential. These spin-offs are funded by venture capital firms (VCs), which are primarily backed by limited partners (LPs)—institutions such as university endowments, pension funds, and family offices.

This is the second gear of the miracle machine: startups and university spin-offs supported by private capital.

Biotech startups primarily focus on scaling and expanding the initial science they’re built upon, navigating the arduous and lengthy process of gaining approval for new drugs. This process doesn’t end at approval. Drugs must be produced, marketed, and sold globally. This stage is handled by pharmaceutical companies, many of which are century-old multinational giants, in some cases predating even the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the agency responsible for drug approval. Rather than conducting their own R&D, pharma companies primarily acquire assets from biotech firms, often involving full acquisitions.

Large-scale R&D corporations like big pharma are the third major gear of our current miracle machine.

This machine has indeed created miracles.

Genentech’s story is just one example. Groundbreaking academic work at Stanford was spun out into a venture-backed company. The firm successfully used genetic engineering to turn bacterial cells into miniature insulin-producing factories—greatly alleviating a shortage of an essential medicine. In 2009, Genentech merged with Swiss pharmaceutical giant Roche in a $47 billion deal, promising global scale.

The story doesn’t end there. Breakthrough technologies like cell therapies and CRISPR gene editing are still transitioning from academic labs to clinical application. Academic labs continue to develop new theories and models, while companies continue to form and raise funding based on the most promising advances. The pharmaceutical industry remains the primary global buyer and distributor. The system has reached a kind of stable equilibrium among its participants.

Despite the miracle machine improving our world, systemic challenges have emerged over time. We provide this bird’s-eye view of the current system to help readers better understand some of these problems and to offer context for new projects seeking to solve them.

Large funding bodies like the NIH have become increasingly bureaucratic over time, inherently favoring conservative and incremental work. It’s safe to say no one truly believes scientists should spend up to 40% of their time struggling through tedious government paperwork. As the funding process grows more complex and committee-driven, novel and promising research directions become harder to support.

The NIH has also developed an interest in “big science” projects—organizing large research teams to undertake projects individual labs cannot complete. While this may seem important in principle, the results of such projects have been mixed, and they consume resources that could otherwise fund labs focused on fundamental discovery science. As UC Berkeley biologist Michael Eisen put it, “Big biology projects are not a boon for individual-driven discovery science. Ironically and tragically, they are becoming the greatest threat to its continued existence.”

Structural shifts in government research funding have shaped and constrained the types of scientific questions researchers can pursue. The handoff between universities and startups has also grown more complicated. During the translational phase, terms for university spin-offs have proven highly variable, sometimes crippling companies before they even launch. Universities are strongly incentivized to tightly protect their IP, which can lead to worse terms for scientists—or even terms so unfavorable that investors lose interest in funding translational efforts.

Government agencies aren’t the only part of the system with funding blind spots. Venture capitalists also face inherent constraints on what they can invest in—companies must have the potential to generate billion-dollar-plus exits for the math to justify investment. Not all technologies or public goods can produce such returns, especially within investors’ constrained time horizons. Only a small fraction of society has the opportunity to gain real wealth by supporting these private investments as accredited investors, further exacerbating inequality.

Pharmaceutical companies are similarly constrained by their financial structures and incentive models. The clear incentive is to develop or acquire drugs for the largest markets while minimizing R&D costs. This suboptimally distorts the entire pipeline, with real consequences: “Despite significant unmet needs and disease burdens, there are hardly any products in the pipeline addressing antimicrobial resistance, tuberculosis, and opioid dependence. In contrast, many new products are new versions of existing ones, making only minor changes to current drugs.”

So where should we look for new ideas and approaches?

Radical solutions are unlikely to come from leaders of our current institutions, as they have incentives to perpetuate the system they inhabit. An interesting direction for finding new ideas is exploring side projects pursued by innovative scientists. As Paul Graham said about great startup ideas, “The best ideas almost have to start as side projects, because they’re always so strange that your mind rejects them as company ideas.”

Taking this approach, it’s hard to ignore the steady expansion of activity within the decentralized science community.

Killer Web3 Use Cases

Personally, I was initially highly skeptical of web3. As a scientist and engineer, one of my core focuses has been leveraging the powerful tools of web2—efficient centralized databases, fast servers, powerful modern browsers—to build cutting-edge research tools for scientists. Technical assessments like Moxie Marlinspike’s early impressions of web3 have formed the foundation of my thinking about this space.

But over time, I’ve become a cautious optimist—ironically, precisely when the crypto market crashed and skepticism toward web3 increased. Why? When I spoke with smart people like Packy, Jocelynn, and leading founders in the field, I grew excited about the domains where this new stack of protocols, tools, and ideas might excel. We’re witnessing important social experiments attempting to build new modes of collaboration and organization. From my direct experience in academic science, I know our research institutions could benefit from changing the status quo.

Readers of Not Boring may be familiar with our fearless leader Packy’s recent involvement in the heated debate over web3’s killer use case. One tangible advantage of web3 is that it provides a new toolkit for creating financial instruments. As Michael Nielsen points out, “New financial tools can in turn be used to create new markets and enable new forms of collective human behavior.”

What if one of the killer applications of this new tech stack is radically improving the process of funding scientific research?

As we’ve emphasized so far, research funding used to roughly fall into two categories: public or private financing. Once cryptocurrency investors began generating massive wealth, a third category of funding emerged—and many of these new investors wanted to deploy their capital for beneficial purposes.

This shift alone is worth pausing to consider. The expansion of cryptocurrency has created a new type of billionaire—primarily those willing to be early adopters of an entirely new financial system. As Tyler Cowen argues, this could transform philanthropy, as these new tech elites may have greater interest in “weird, independent projects.” We’re already seeing this dynamic play out, with Vitalik Buterin and Brian Armstrong both making major investments in longevity science initiatives.

This difference extends beyond just the emergence of a younger, more tech-oriented cohort of investors and philanthropists. Web3 technologies are being used to strengthen funding for novel and unconventional science projects. Today, new financing mechanisms—including token sales and cryptocurrency-backed crowdfunding—are introducing an entirely new way to fund projects.

Crowdfunding has traditionally been challenging for scientific research, but crypto-based crowdfunding may be changing that. A suite of new open protocols and tools has emerged, aimed at scaling up funding for public goods. One example is Gitcoin, an organization dedicated to building and funding public goods. Each quarter, they run a crowdfunding round supported by major donors like Vitalik Buterin. The interesting innovation here is quadratic funding—grants matched in a way that values the number of donors more than the size of donations. In the latest GR15 grant round, decentralized science (DeSci) was listed as one of four impact categories, underscoring growing interest in scientific research within the web3 space.

Gitcoin GR15 Grant Round

https://x.com/umarkhaneth/status/1575147449752207360

The DeSci round received contributions from 2,309 unique contributors, supporting 83 projects and raising $567,983. A group of notable large donors provided matching funds, including Vitalik Buterin (co-founder of Ethereum), Stefan George (co-founder and CTO of Gnosis), Protocol Labs, and… Springer Nature Group.

The scientific community is adopting another blockchain innovation: Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs).

As Packy previously described, DAOs are an innovation in web3 governance. DAOs “run on blockchains, giving decision-making power to stakeholders rather than executives or board members.” They are “autonomous” because they rely on software protocols recorded on publicly accessible blockchains that “trigger actions when certain conditions are met, without human intervention.”

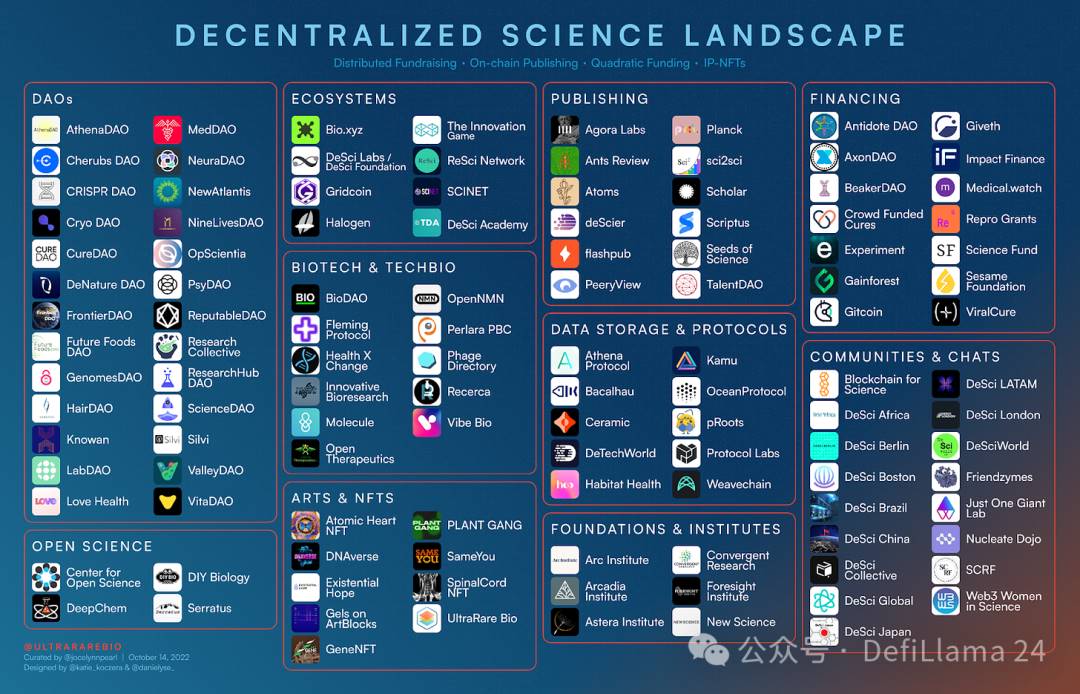

Just as with Gitcoin and quadratic funding, one of the most exciting early use cases for DAOs is accelerating the formation and funding of scientific communities. Over the past year, scientific DAOs have undergone a kind of Cambrian explosion. Here’s an overview of some DAOs and projects in the space:

UltraRare Bio compiled and updated this snapshot of the DeSci landscape on October 13, 2022

UltraRare Bio compiled and updated this snapshot of the DeSci landscape on October 13, 2022

If we see traditional science as a “top-down approach” occurring within established, highly centralized university hubs, then scientific DAOs demonstrate an emerging “bottom-up” trend in scientific development. Many of the communities showcased in this space form when groups adopt shared goals—for example, advancing research in agriculture or hair loss. These are not just Reddit-like discussion forums; most DAOs include dedicated working groups, often mixing experts with amateur scientists, tasked with activities such as conducting new literature reviews in their area of interest or evaluating projects for funding.

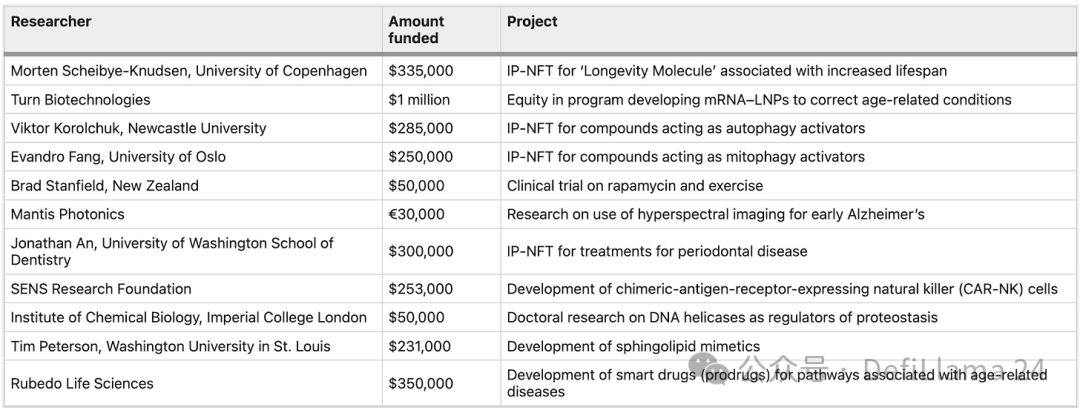

One of DeSci’s original promises is democratizing access to funding—essentially enabling research that previously couldn’t secure funding to now receive support. But is this true for community-funded projects like those in VitaDAO’s Deal Flow Working Group? Among the projects listed on their website, several university researchers have received grants of around $200,000–$300,000.

How do researchers funded by VitaDAO differ from those receiving traditional NIH funding? Take Dr. Evandro Fang, whose project on novel mitophagy activators recently received a $300,000 investment from VitaDAO. According to his CV, his work has previously received multiple NIH and other government grants. Another argument for the novelty of VitaDAO’s approach is that their community review and funding processes are faster than NIH’s—even if the recipients show high overlap.

So far, DeSci communities like Gitcoin’s crowdfunding initiatives and organizations like VitaDAO have focused on accelerating and streamlining the funding process for basic research. Other projects have begun targeting weaknesses we’ve highlighted in the biopharma industry, such as drug development for rare diseases.

Another early selling point of the DeSci space is its ability to advance treatments for underserved patient populations, such as those with ultra-rare diseases. Traditional biotech companies typically avoid drug development for smaller patient groups because they can’t generate enough profit from the final product to justify the high costs of clinical R&D. However, decentralized global teams are advancing efforts to identify drug repurposing for rare disease patients. Examples include Perlara and Phage Directory, neither of which relies on blockchain technology, but both support the argument that knowledge from distributed networks can advance treatment development.

On the front of blockchain-based organization, Vibe Bio is a new company embracing web3 as a pathway to “a treatment for every condition in every community.” Vibe founders Alok Tayi and Joshua Forman plan to build a web3 protocol for establishing patient community DAOs that can collectively own and manage their drug development. This is an exciting innovation in a domain where patient communities have self-organized for decades, but data and assets are usually owned by companies. This poses risks to patient foundations that often seed-fund science. Companies can choose to shelve these projects, as Taysha Gene Therapies recently did with its Leigh syndrome program.

Vibe recently raised $12 million from traditional VC firms, including Not Boring Capital—a positive signal that connecting patient communities via DAOs may become a viable process for developing rare disease treatments. Founder Alok Tayi was inspired to start Vibe after his daughter was born with an incurable condition. In an interview with the Not Boring podcast, when asked “Why web3?”, Tayi responded:

Our goal is to create an infrastructural approach through which we can potentially address all neglected and ignored diseases. So we first needed to think about technological and governance solutions that allow us infinite scalability of participation, plus a completely new source of capital—one interested in bold action and accomplishing big things.

The constraints of biotech venture capital push them toward slightly more conservative investments, rather than a broader range of diseases. Another aspect I want to emphasize is that when you look at other potential approaches—whether charities, academic institutions, or even C-corps or LLCs—they ultimately have inherent limitations in the amount of funding, types of expertise, and number of owners and participants who can practically engage in the process. So our ambition at Vibe, our mission, is to find a treatment for every community—not just the 250 accredited investors or qualified buyers allowed to participate in these traditional institutional models.

Beyond cryptocurrency funding and DAOs, many novel ideas are exploring how tokenomics can be applied to science to improve some of its shortcomings. These strategies include IP-NFTs—essentially intellectual property tied to non-fungible tokens. A company called Molecule pioneered the proof-of-concept implementation of this for biopharmaceutical assets. They aim to create an “open market for drug development.”

The convergence of web3 and science is still in its very early stages; time will tell how these new experiments in scientific funding, ownership, and organization evolve. We remain optimistic that even if blockchain isn’t the answer to the crisis in the scientific ecosystem, it has at least reignited discussions about what needs fixing and begun allocating this new form of liquidity to one of its best use cases.

Faster Gas, Faster Funding

Experiments in decentralized science demonstrate enormous enthusiasm within the web3 community for funding scientific research and commercialization. This shouldn’t be underestimated. While the NIH has a $50 billion annual budget, it still requires constant political maneuvering to convince American taxpayers to expand the scope and scale of scientific spending. Given this stark contrast in enthusiasm, it’s entirely conceivable that a trillion-dollar crypto market could surpass U.S. government spending on science worldwide.

Beyond cryptocurrency, tech philanthropists are also targeting key inefficiencies in our modern scientific funding system. A prominent example is the deployment of emergency funding during pandemics. Even in the face of a global emergency, the NIH demonstrated an inability to deviate from its rigid funding structure:

The cumbersome process scientists had to follow to obtain emergency NIH funding during the pandemic

https://x.com/patrickc/status/1399795033084096512

To deploy funds faster, the Fast Grants initiative was launched. Initiated by Emergent Ventures and supported by a range of prominent tech leaders including Elon Musk, Paul Graham, and the Collison brothers, the project aimed to drastically shorten the timeline for launching critical COVID-19-related research. Their argument was simple: “In normal times, scientific funding mechanisms are too slow; during the COVID-19 pandemic, they might be even slower. Fast Grants is an effort to correct that.”

There’s an important lesson here, requiring us to revisit our mental model of how the NIH was originally established. As we see today, our current funding system was largely designed by visionary Vannevar Bush, a key figure in the Defense Research Committee (NDRC) during WWII, known for delivering rapid results. Part of Fast Grants’ mission is to return to the kind of efficient system Bush himself advocated. In his memoir, Bush recalled: “Within a week, the NDRC could review a project. The next day, the director could authorize it, the business office could issue a letter of intent, and actual work could begin.”

Initially intended to accelerate research and understanding of COVID-19 during a global pandemic, this model appears attractive beyond this single use case. In an article written for Future, Tyler Cowen, Patrick Hsu, and Patrick Collison reflected on some of the project’s outcomes:

We expected to receive at most a few hundred applications. Yet within a week, we received 4,000 serious applications, with almost no spam. Within days, we began disbursing millions in grants, and during 2020, we raised over $50 million, awarding more than 260 grants. All of this was achieved with Mercatus overhead under 3%, partly thanks to the infrastructure built for Emergent Ventures, which was also designed to rapidly and efficiently distribute (non-biomedical) grants.

Incredibly, approved grantees received funds within 48 hours. Second-round funding followed within two weeks. Grantees were required to publish results openly and share brief monthly updates.

Among some interesting findings, many applicants came from top universities—groups organizers assumed were already well-supported by traditional NIH-style funding. And 64% of surveyed grantees said the research wouldn’t have happened without Fast Grants. Again quoting Collison, Cowen, and Hsu:

Fast Grants goes for low-hanging fruit, picking the most obvious bets. Its unusual aspect isn’t coming up with clever grant targets, but finding a mechanism to actually execute. To us, this suggests mainstream institutions may lack smart managers who can be trusted with flexible budgets and empowered to allocate funds quickly without triggering massive red tape or committee-driven consensus.

Fast Grants is a model being adopted by multiple organizations. One example is Impetus Grants, founded and led by 22-year-old Thiel Fellow Lada Nuzhna, focused on longevity research. The first round funded 98 projects, aiming to accelerate biomarker research in aging, understand aging mechanisms, and improve the translation of research to clinics. While one explicit goal of the project is to fund research potentially overlooked by traditional sources, the list of grantees includes several prominent longevity researchers, and its acceptance rate is actually stricter than NIH’s (15% for Impetus Grants vs. ~20% for NIH). Notably, one important aspect of such experiments is that they may push NIH to adopt and scale some of the most promising new strategies. The Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) initiative was launched by NIH around the same time Fast Grants launched.

In the coming years, it will be fascinating to compare how different funding models change the composition of who can conduct research and the types of outcomes these researchers produce. These diverse projects highlight two interesting trends.

First, beyond crypto markets, a new generation of tech philanthropists shows genuine interest in funding science in new ways.

Second, sometimes less is more.

As we explore new forms of funding, it’s worth recognizing that writing grant proposals should be secondary—actual scientific research should be primary. Sometimes, the best solution is to quickly evaluate and fund the most promising proposals, then get out of the way.

Going Full Bucky (Building from Scratch)

So far, we’ve outlined roughly how current institutions operate and seen how crypto markets, web3 technologies, and tech philanthropists are contributing to the research funding landscape. We now live in a world where Vitalik Buterin supports quadratic crowdfunding for science projects, and the Collison brothers back low-overhead grant mechanisms to counteract governmental inefficiency. These new ideas are being explored in exciting and important ways to accelerate and expand the miracle machine.

With all these new efforts underway, an interesting question emerges: What if some of the problems in scientific funding cannot be solved simply by new sources of funding or new grant mechanisms?

Ultimately, our current scientific institutions represent only a small sample of the full space of possible organizational structures. The miracle machine we have is a byproduct of a very specific set of historical pressures and ideas. Some of the new funding ideas being explored today require building entirely new 21st-century scientific institutions. In other words, they are embodying Buckminster Fuller’s philosophy, starting from scratch to explore new ways of funding and organizing science.

How can new real-life (IRL) research institutes be built to address missing links in science?

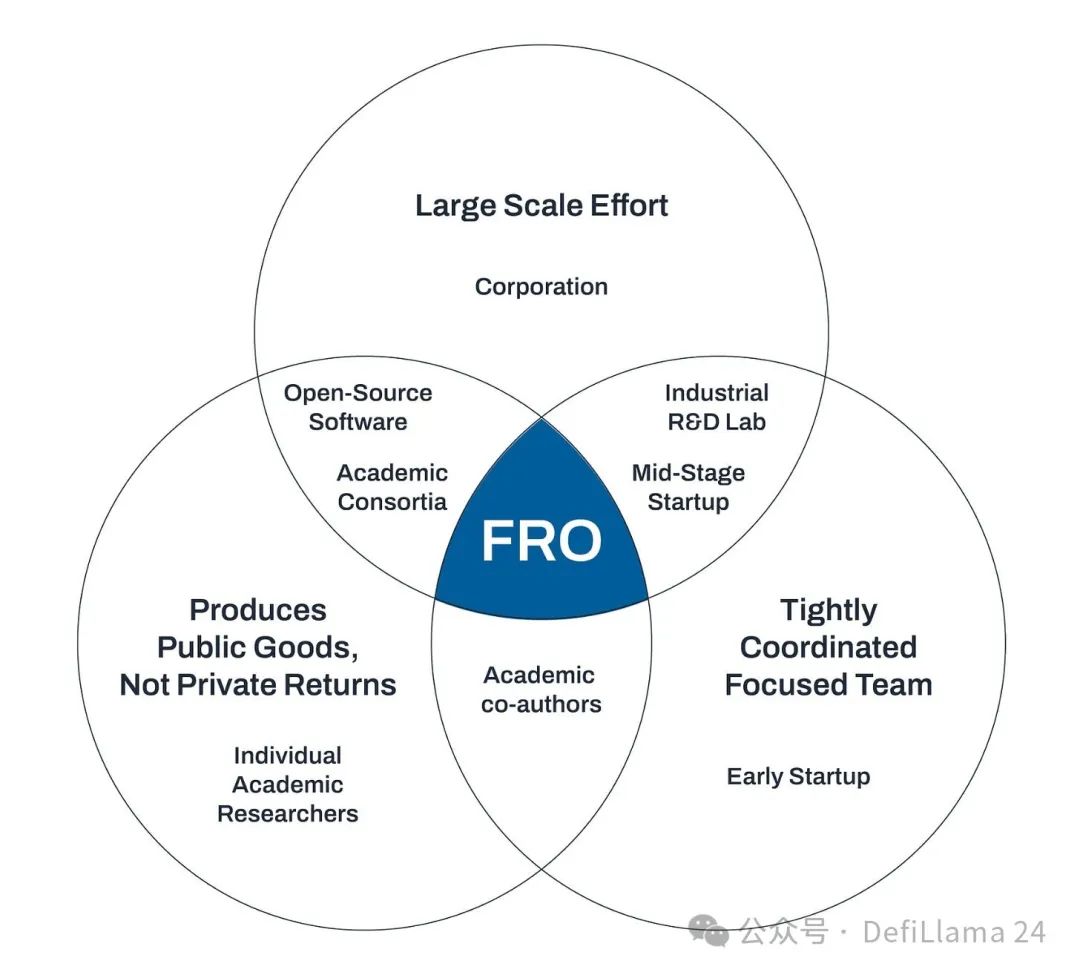

One approach is Focused Research Organizations (FROs)—a new type of institution dedicated to solving specific scientific challenges, such as blue-sky neurotechnology or longevity research. Other proposed focus areas for FROs include identifying antibodies for every protein, mathematical AI, and developing super-durable organ transplants. The core idea behind the FRO model is that these types of scientific projects fall into an institutional gap. They are too capital-intensive and team-oriented for academia, yet don’t fit within startups or large corporations because they resemble public goods more than products with clear commercial value. FROs aim to fill this void:

Convergent Research, co-founded by Adam Marblestone and Anastasia Gamick, aims to incubate new FROs. This spring, CR hosted a metascience workshop bringing together institute leaders, policymakers from Washington D.C. and the UK, writers, and changemakers in the metascience space. The main goal of the workshop was to brainstorm how new organizations can drive scientific progress.

A recurring theme across speaker presentations was that the scientific ecosystem is broken. Summarizing this working hypothesis: the dominant model of university-based research published in traditional scientific journals is creating a fragile ecosystem in need of disruption.

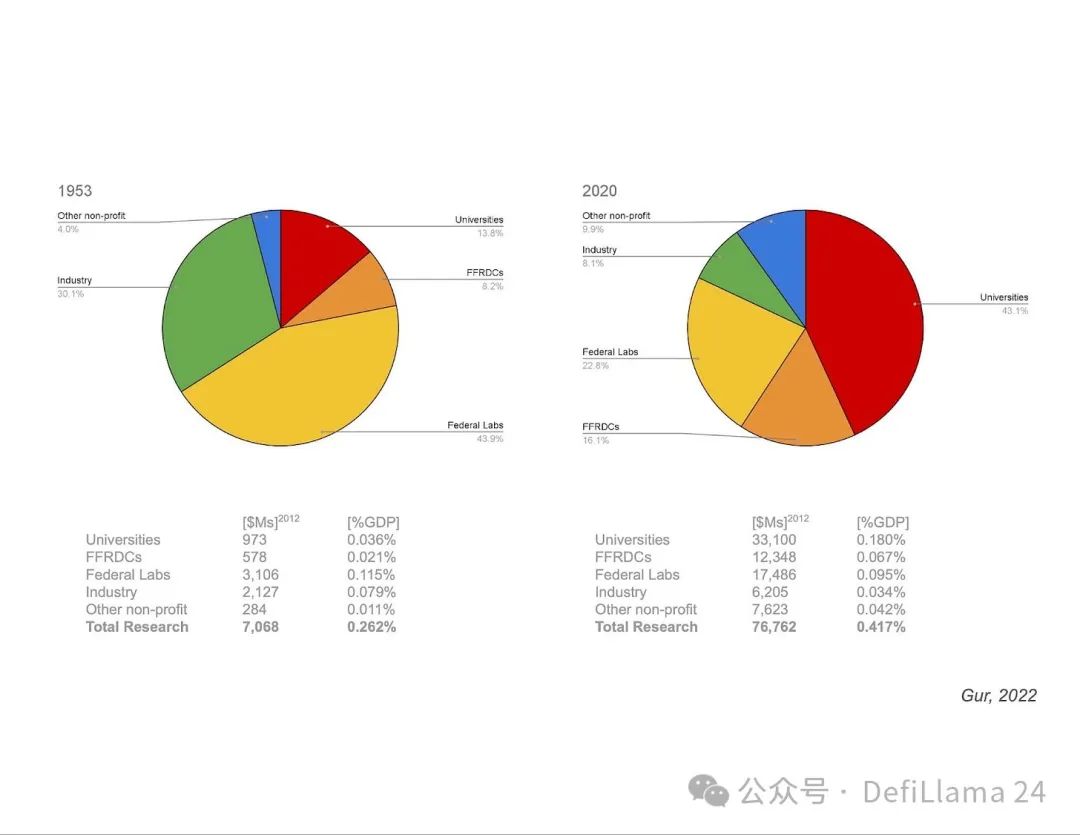

In a talk by Ilan Gur (then CEO of Activate.org, now CEO of Aria Research), we saw a pie chart showing the distribution of research funding over time.

This chart reveals something very interesting. The massive reorganization of research funding after WWII coincides precisely with a major shift in the composition of our research institutions. U.S. basic research funding shifted from primarily funding federal labs (1953, left pie chart) to predominantly funding university research (2020, right pie chart). Could this shift toward a university-centric funding model be responsible for some of the flaws in our current ecosystem?

In another talk, we watched a video clip of scientists at the Santa Fe Institute discussing setting magic:

Clip from a forthcoming documentary about the Santa Fe Institute

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xc6IHZosKY8

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News