Arthur Hayes' new article: Bitcoin's Million-Dollar Path and the New Model of Quantitative Easing Under "Trumponomics"

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Arthur Hayes' new article: Bitcoin's Million-Dollar Path and the New Model of Quantitative Easing Under "Trumponomics"

As Bitcoin's circulating supply decreases, large amounts of fiat currency worldwide will compete to seek safe-haven assets—not only from U.S. investors but also from those in China, Japan, and Western Europe.

Author: Arthur Hayes

Translation: TechFlow

(The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and should not be taken as investment advice or a basis for making investment decisions.)

What do you think Bitcoin’s price will be on December 31, 2024? Above $100,000 or below $100,000?

There is a famous Chinese saying: "It doesn't matter if a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice."

I will refer to the policies implemented by President Trump following his re-election as “American capitalism with Chinese characteristics.”

The elites ruling Pax Americana don’t care whether the economic system is capitalism, socialism, or fascism—they only care whether the policies enacted help maintain their power. America ceased being pure capitalism as early as the beginning of the 19th century. Capitalism implies that when the rich make bad decisions, they lose money. That possibility was outlawed back in 1913 with the creation of the Federal Reserve System. As privatized gains and socialized losses took hold, extreme class divisions emerged between the "despicable" or "lower-class" people living inland and the noble, respected coastal elite. President Roosevelt had to correct course by throwing some bread crumbs to the poor through his “New Deal” policies. Then, as now, expanding government relief to the underclass was not a policy welcomed by wealthy so-called capitalists.

The shift from extreme socialism (in 1944, the top marginal tax rate on income over $200,000 rose to 94%) to unfettered corporate socialism began in the 1980s under Reagan. Since then, central banks have printed money and injected it into financial services, hoping wealth would trickle down from the top—a neoliberal economic model that lasted until the 2020 COVID pandemic. In responding to the crisis, President Trump revealed his inner Roosevelt; for the first time since the New Deal, he directly distributed the largest amount of money to the general population. The U.S. printed 40% of all dollars globally between 2020 and 2021. Trump initiated the issuance of "stimulus checks," and President Biden continued this popular policy during his term. When assessing the impact on government balance sheets, some strange phenomena emerged between 2008–2020 and 2020–2022.

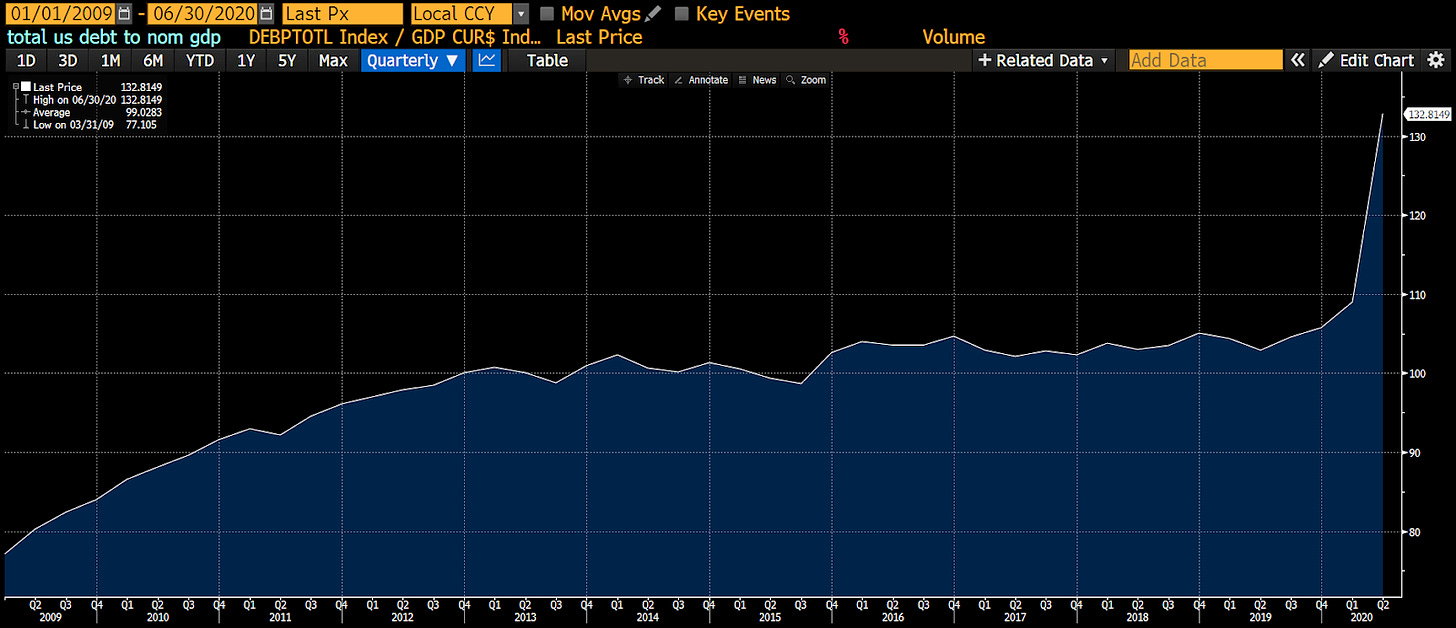

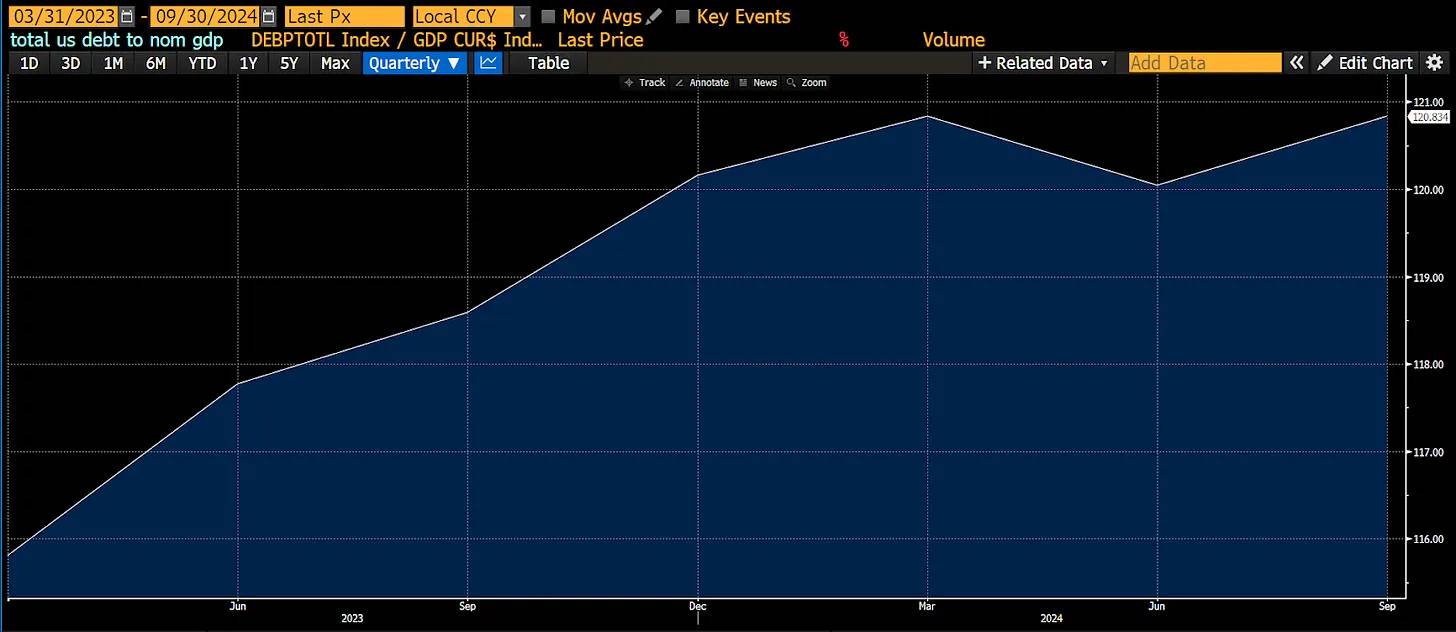

From Q2 2009 to Q2 2020 marked the peak of so-called "trickle-down economics," where economic growth relied heavily on central bank money printing, commonly known as quantitative easing (QE). As you can see, nominal GDP grew more slowly than national debt accumulation. In other words, the rich used funds received from the government to buy assets. Such transactions did not generate real economic activity. Therefore, pumping trillions of dollars into the hands of wealthy financial asset holders increased the debt-to-nominal-GDP ratio.

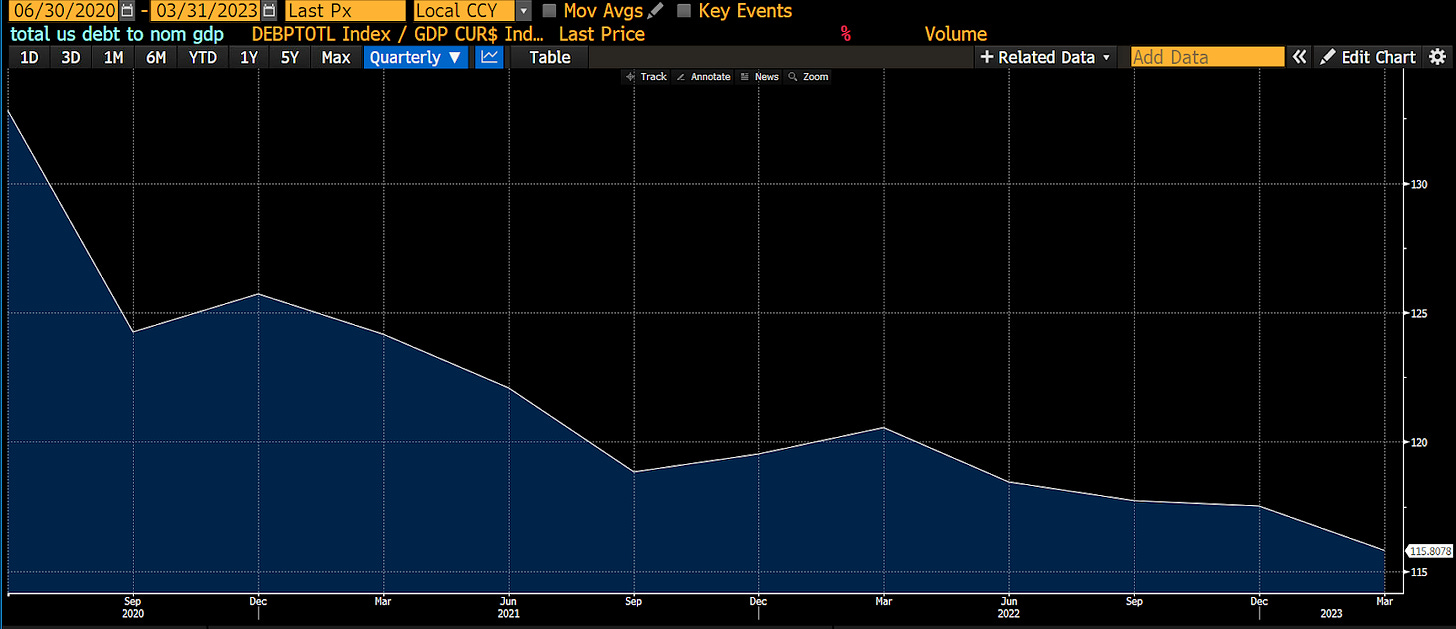

From Q2 2020 to Q1 2023, Presidents Trump and Biden adopted a different approach. Their Treasury issued debt purchased by the Fed via QE—but this time, instead of giving money to the rich, they mailed checks directly to every citizen. Poor people actually received cash in their bank accounts. Clearly, Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase, profited significantly from transaction fees on government transfers… he's known as America's Li Ka-shing—you can’t avoid paying him. The poor spend all their money on goods and services, and during this period, they certainly did just that. With a significant increase in the velocity of money, economic growth accelerated. That is, one dollar of debt generated more than one dollar of economic activity. Thus, the U.S. debt-to-nominal-GDP ratio magically declined.

However, inflation intensified because supply of goods and services failed to keep pace with the purchasing power gained by people through government debt. Wealthy bondholders were unhappy with these populist policies. They experienced their worst total returns since 1812. In response, they sent Federal Reserve Chair Jay Powell to fight inflation by raising interest rates starting in early 2022—while ordinary citizens hoped for another round of stimulus checks, which were now forbidden. U.S. Treasury Secretary Yellen stepped in to offset the tightening effects of the Fed’s monetary policy. She shifted debt issuance from long-term bonds to short-term bills, draining the Fed's reverse repo facility (RRP). This injected nearly $2.5 trillion in fiscal stimulus into markets, primarily benefiting wealthy financial asset holders—the asset market boomed. Similar to post-2008, this government aid to the rich did not produce real economic activity, and the U.S. debt-to-nominal-GDP ratio began rising again.

Will Trump’s incoming cabinet learn from recent American economic history? I believe yes.

Scott Bessent, widely seen as Trump’s pick to succeed Yellen as U.S. Treasury Secretary, has delivered numerous speeches outlining how he would “fix” America. His speeches and columns detail the execution of Trump’s “America First Plan,” which bears striking resemblance to China’s development strategy (initiated during Deng Xiaoping’s era in the 1980s and continuing today). The plan aims to boost nominal GDP by incentivizing key industries (such as shipbuilding, semiconductor fabs, auto manufacturing) to reshore through government-provided tax credits and subsidies. Eligible companies will gain access to low-interest bank loans. Banks will once again actively lend to these operating businesses because profitability is guaranteed by the U.S. government. As firms expand operations in the U.S., they’ll need to hire American workers. Higher-paying jobs for average Americans mean increased consumer spending. These effects will be amplified if Trump restricts immigration from certain countries. These measures stimulate economic activity, allowing the government to collect revenue via corporate profits and personal income taxes. To support these programs, high budget deficits will be required, financed by Treasury sales of bonds to banks. With the Fed or lawmakers suspending the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR), banks can now re-lever their balance sheets. Winners include ordinary workers, companies producing “qualified” goods and services, and the U.S. government, whose debt-to-nominal-GDP ratio declines. This policy amounts to supercharged quantitative easing for the poor.

Sounds great. Who could oppose such a prosperous American era?

The losers are those holding long-term bonds or savings deposits, as yields on these instruments will be deliberately kept below the nominal growth rate of the U.S. economy. You'll also suffer if your wages fail to keep up with higher inflation. Notably, unionization is becoming trendy again. “4 and 40” has become the new slogan—demanding a 40% wage increase over the next four years, or 10% annually, to incentivize continued work.

For readers who consider themselves wealthy: don’t worry. Here’s an investment guide. This isn’t financial advice—I’m simply sharing what I do in my personal portfolio. Whenever legislation passes allocating funds to specific sectors, read it carefully, then invest in stocks within those industries. Instead of keeping money in fiat bonds or bank deposits, buy gold (as baby boomers’ hedge against financial repression) or Bitcoin (as millennials’ hedge against financial repression).

Clearly, my investment portfolio prioritizes Bitcoin, other cryptocurrencies, and crypto-related company stocks, followed by gold stored in vaults, and lastly equities. I keep a small amount of cash in money market funds to pay my Amex bill.

In the remainder of this article, I will explain how QE for the rich versus QE for the poor affects economic growth and money supply. Then, I will predict how exempting banks from the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR) could once again enable infinite QE for the poor. Finally, I will introduce a new index tracking U.S. bank credit supply and show how Bitcoin outperforms all other assets when adjusted for bank credit availability.

Money Supply

I deeply admire the high quality of Zoltan Pozar’s Ex Uno Plures series. During my recent long weekend in the Maldives—enjoying surfing, Iyengar yoga, and fascial massage—I devoured all of his writings. His insights will appear frequently throughout the rest of this piece.

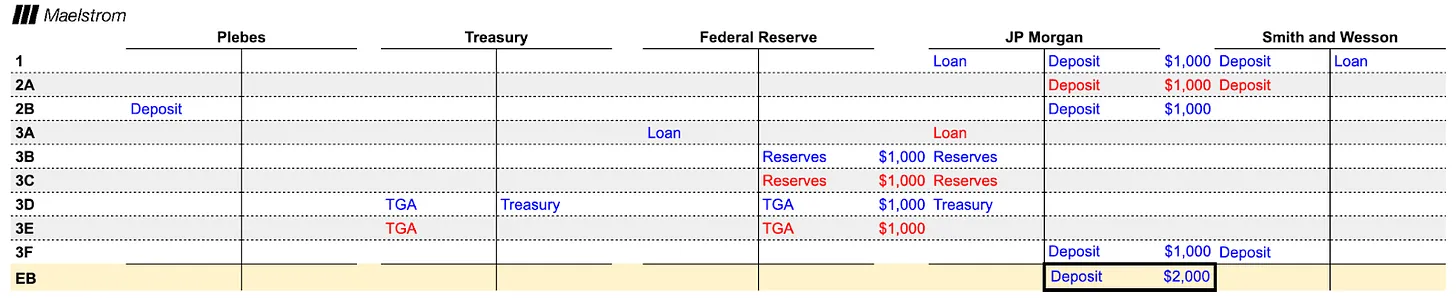

Next, I present a series of hypothetical accounting ledgers. On the left side of the T-account are assets, on the right are liabilities. Blue entries indicate value increases, red entries indicate decreases.

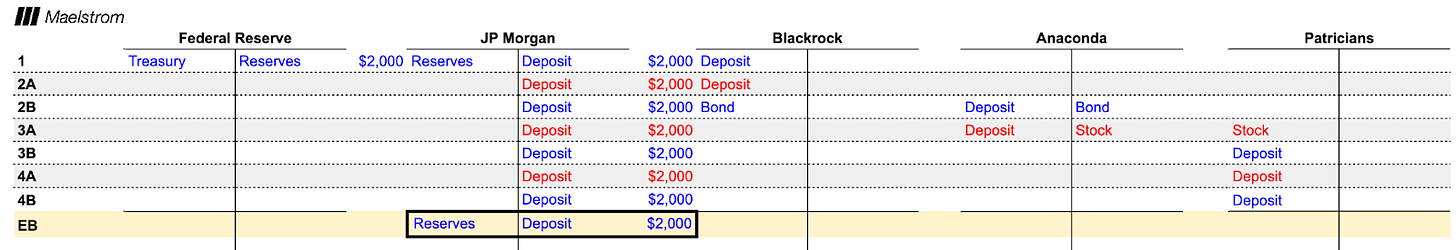

The first example focuses on how the Fed’s QE bond purchases affect money supply and economic growth. Of course, this and subsequent examples contain a touch of humor to enhance engagement.

Imagine you are Powell during the U.S. regional banking crisis in March 2023. For stress relief, Powell heads to the Racquet and Tennis Club at 370 Park Avenue in NYC to play squash with a billionaire old friend. Powell’s friend is extremely anxious.

This friend—we’ll call him Kevin—is a veteran financier who says: “Jay, I might have to sell my Hamptons house. All my money was in Signature Bank, clearly exceeding FDIC insurance limits. You’ve got to help me. You know how unbearable it is for rabbits like us to stay in the city all summer.”

Jay replies: “Don’t worry, I’ll fix it. I’ll do $2 trillion in QE. Announced Sunday night. You know the Fed always has your back. Without your contributions, who knows what America would become. Just imagine if Trump regained power because Biden had to deal with a financial crisis. I still remember how Trump stole my girlfriend at Dorsia back in the early ’80s—so annoying.”

The Fed created the Bank Term Funding Program, which differs from direct QE, to resolve the banking crisis. But allow me some artistic liberty here. Now let’s examine how $2 trillion in QE impacts money supply. All figures are in billions of dollars.

-

The Fed buys $200 billion in Treasuries from BlackRock, paying via reserves. JP Morgan acts as intermediary in this transaction. JP Morgan receives $200 billion in reserves and credits BlackRock with a $200 billion deposit. The Fed’s QE leads banks to create deposits—which ultimately become money.

-

BlackRock, now lacking Treasuries, must reinvest this capital into other interest-bearing assets. Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, typically only works with industry leaders—and right now, he’s intrigued by tech. A new social networking app called Anaconda is building a user community sharing uploaded photos. Anaconda is in growth mode, and BlackRock is happy to buy $200 billion in its bonds.

-

Anaconda has become a major player in U.S. capital markets. It successfully captured the 18–45 male demographic, addicting them to the app. Because users reduced reading time and spent more browsing the app, their productivity dropped sharply. Anaconda funds stock buybacks via debt issuance for tax optimization, avoiding repatriation of overseas retained earnings. Reducing share count boosts both stock price and EPS (since the denominator shrinks). Passive index investors like BlackRock prefer buying such stocks. As a result, the nobility ends up with $200 billion more in their bank accounts after selling shares.

-

The wealthy shareholders of Anaconda don’t urgently need this cash. Gagosian throws a lavish party at Art Basel Miami. At the event, the aristocrats decide to purchase new artworks to elevate their status as serious art collectors and impress beauties at the booths. The sellers of these artworks belong to the same economic class. Buyers’ accounts are credited, sellers’ debited.

After all these transactions, no real economic activity was created. By injecting $2 trillion into the economy, the Fed merely increased the bank balances of the rich. Even financing a U.S. company didn’t generate economic growth—because the funds were used to inflate stock prices rather than create new jobs. One dollar of QE increased money supply by one dollar but produced zero economic activity. This is not a rational use of debt. Hence, during QE periods from 2008 to 2020, the debt-to-nominal-GDP ratio rose among the rich.

Now let’s examine President Trump’s decision-making process during COVID. Back to March 2020: early in the pandemic, Trump’s advisors urged him to “flatten the curve.” They recommended shutting down the economy, allowing only “essential workers”—typically low-paid individuals keeping things running—to continue working.

Trump: “Do I really need to shut down the economy because some doctors say this flu is severe?”

Advisor: “Yes, Mr. President. I must remind you that it’s primarily elderly people like yourself who face complications from COVID-19. Also, treating the entire 65+ cohort if hospitalized would be extremely expensive. You need to lock down all non-essential workers.”

Trump: “That’ll crash the economy. We should send everyone checks so they won’t complain. The Fed can buy Treasury debt issued to fund these subsidies.”

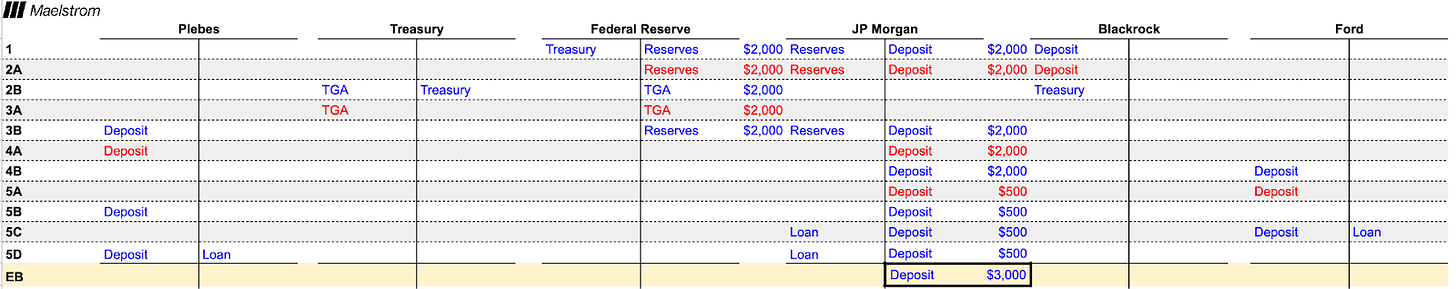

Next, using the same accounting framework, let’s walk through how QE affects ordinary people.

-

As in the first example, the Fed conducts $200 billion in QE by buying Treasuries from BlackRock, paying via reserves.

-

Differing from the first example, the Treasury now participates in the flow. To fund Trump’s stimulus checks, the government needs to raise money via bond issuance. BlackRock chooses to buy Treasuries instead of corporate bonds. JP Morgan helps BlackRock convert its bank deposits into Fed reserves usable for Treasury purchases. The Treasury gains a deposit in its General Account (TGA) at the Fed—similar to a checking account.

-

The Treasury mails stimulus checks to everyone—mainly the broad masses of ordinary people. This reduces the TGA balance while increasing reserves held at the Fed, which become bank deposits for ordinary people at JP Morgan.

-

Ordinary people spend all their stimulus checks buying new Ford F-150 pickup trucks. Ignoring EV trends, this is America—they still love gas guzzlers. Ordinary people’s bank accounts are debited; Ford’s account is credited with new deposits.

-

When Ford sells these trucks, two things happen. First, it pays worker wages, transferring deposits from Ford’s account to employees’ accounts. Second, Ford applies for a bank loan to scale production; the loan creates new deposits and expands money supply. Finally, ordinary people plan vacations and take personal loans from banks—given strong economic conditions and high salaries, banks happily extend credit. Personal loans create additional deposits, just as Ford’s borrowing did.

-

The final deposit or money balance totals $300 billion—$100 billion more than the $200 billion initially injected by the Fed’s QE. From this example, we see that QE for ordinary people stimulates economic growth. Stimulus checks encourage consumption of trucks. Demand for goods allows Ford to pay wages and borrow to expand. High-income workers gain access to bank credit, enabling further consumption. One dollar of debt generates more than one dollar of economic activity. A positive outcome for the government.

I’d like to further explore how banks can infinitely finance the Treasury.

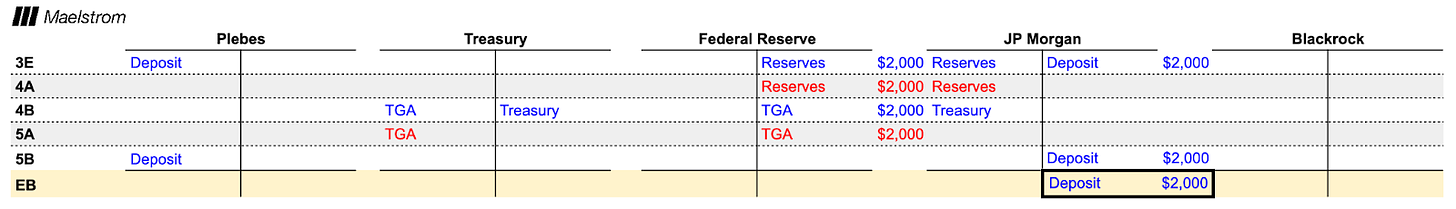

We begin from step 3 above.

-

The Treasury begins issuing another round of economic stimulus. To fund this, it auctions bonds, and JPMorgan, as primary dealer, uses its Fed reserves to buy them. After the sale, the Treasury’s TGA balance increases.

-

As before, stimulus checks issued by the Treasury end up deposited into ordinary people’s accounts at JPMorgan.

When the Treasury issues bonds purchased by the banking system, it transforms otherwise idle Fed reserves into deposits for ordinary people—deposits usable for spending, thereby driving economic activity.

Now consider another T-account example. What happens when the government encourages enterprises to produce specific goods and services through tax breaks and subsidies?

In this case, America runs out of bullets while filming a Gulf War shoot-out inspired by Clint Eastwood westerns. The government passes a bill promising to subsidize ammunition production. Smith & Wesson applies and wins a contract to supply ammo to the military but cannot produce enough bullets to fulfill it—so it applies to JPMorgan for a loan to build a new factory.

-

JPMorgan’s loan officer, seeing the government contract, confidently lends $1 billion to Smith & Wesson. This lending act creates $1 billion out of thin air.

-

Smith & Wesson builds the factory, generating wage income that eventually becomes deposits at JPMorgan. The money created by JPMorgan becomes deposits for those most likely to spend—ordinary people. I’ve already explained how ordinary people’s spending habits drive economic activity. Let’s slightly modify this example.

-

The Treasury needs to auction $1 billion in new debt to fund the subsidy to Smith & Wesson. JPMorgan attends the auction but lacks sufficient reserves to pay. Since using the Fed’s discount window no longer carries stigma, JPMorgan pledges its Smith & Wesson corporate debt as collateral to obtain reserve loans from the Fed. These reserves are used to buy newly issued Treasury debt. The Treasury then pays the subsidy to Smith & Wesson, which becomes a deposit at JPMorgan.

This example illustrates how the U.S. government, through industrial policy, induces JPMorgan to create loans—and then uses the resulting assets as collateral to purchase more U.S. Treasury debt.

The Treasury, Fed, and banks seem to operate a magical “money machine” capable of achieving three functions:

-

Increasing financial assets for the rich without generating real economic activity.

-

Injecting funds into the bank accounts of the poor, who typically spend it on goods and services, thus driving real economic activity.

-

Guaranteeing profitability for select firms in specific industries, enabling them to expand via bank credit and thereby stimulating real economic activity.

Are there any limits to such operations?

Of course. Banks cannot create money infinitely because they must back each debt asset with costly equity capital. In technical terms, different asset types carry risk-weighted capital charges. Even “risk-free” government bonds and central bank reserves require equity capital. Thus, at some point, banks become unable to effectively bid for U.S. Treasuries or extend corporate loans.

Banks must provide equity for loans and other debt securities because if borrowers default—whether governments or corporations—someone must absorb the loss. Since banks choose to create money or buy government bonds for profit, it’s fair their shareholders bear these losses. When losses exceed bank equity, the bank fails. Bank failure risks depositors losing savings—bad enough—but systemically worse is the bank’s inability to keep expanding credit in the economy. Since fractional-reserve fiat finance requires continuous credit creation to function, bank failures could collapse the entire financial system like dominoes. Remember—one person’s asset is another’s liability.

When a bank exhausts its equity-based lending capacity, the only way to save the system is for the central bank to create new fiat currency and exchange it for the bank’s bad assets. Imagine if Signature Bank only lent to Su Zhu and Kyle Davies of the now-defunct Three Arrows Capital (3AC). Su and Kyle submitted falsified financial statements, misleading the bank about the fund’s health. Then they withdrew cash from the fund and transferred it to their wives, hoping to shield it from bankruptcy proceedings. When the fund collapsed, the bank had no recoverable assets—the loan became worthless. This is fictional; Su and Kyle are good guys, they wouldn’t do this ;) Signature donated heavily to Senator Elizabeth Warren, a member of the Senate Banking Committee. Leveraging political influence, Signature convinced Senator Warren they deserved rescue. She contacted Fed Chair Powell, requesting the Fed swap 3AC’s debt for cash at face value via the discount window. The Fed complied—Signature exchanged 3AC bonds for newly printed dollars, shielding itself from deposit outflows. Of course, this is purely hypothetical—but the lesson stands: if banks don’t provide sufficient equity capital, society ultimately bears the cost through currency devaluation.

Perhaps my assumption contains a grain of truth; here’s a recent headline from The Straits Times:

The wife of Zhu Su, co-founder of the collapsed crypto hedge fund Three Arrows Capital (3AC), successfully sold her Singapore mansion for $51 million despite court orders freezing other couple’s assets.

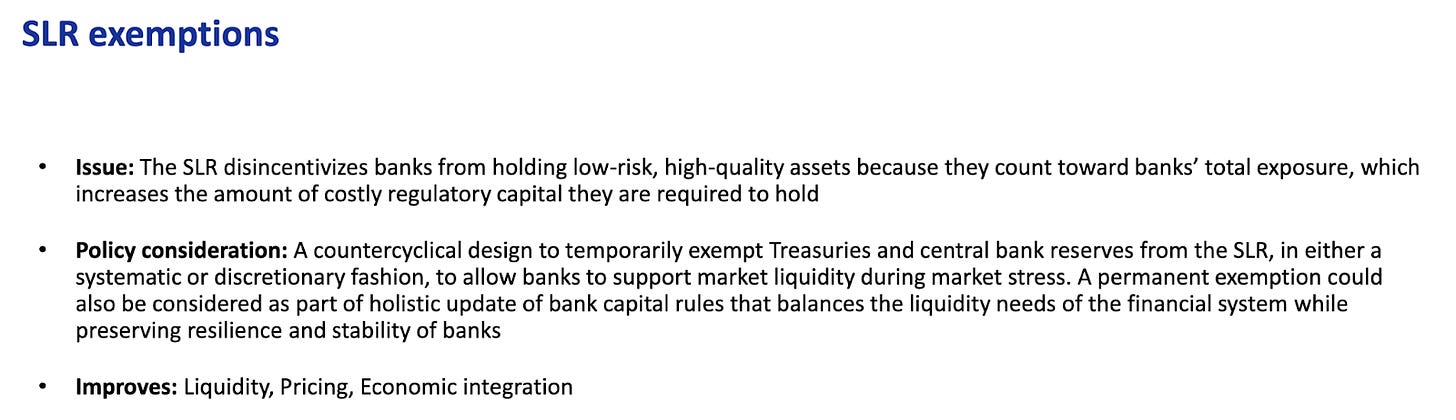

If the government wishes to create unlimited bank credit, it must change the rules so that Treasury debt and certain “approved” corporate debt (e.g., investment-grade bonds or debt issued by firms in strategic sectors like semiconductors) are exempt from supplementary leverage ratio (SLR) requirements.

If Treasuries, central bank reserves, and/or approved corporate debt securities are exempt from SLR constraints, banks can purchase unlimited quantities without bearing costly equity. The Fed has the authority to grant such exemptions—it did so from April 2020 to March 2021. At the time, U.S. credit markets froze. To get banks back into Treasury auctions and lending to the U.S. government—needed to fund trillions in stimulus with insufficient tax revenue—the Fed acted. The exemption worked brilliantly: banks bought Treasuries aggressively. But there was a cost: when Powell raised rates from 0% to 5%, Treasury prices plummeted, triggering the March 2023 regional banking crisis. There’s no free lunch.

Additionally, the level of bank reserves affects willingness to buy Treasuries at auction. When banks feel their Fed reserves have reached the Lower Comfort Level of Reserves (LCLoR), they stop participating. The exact LCLoR value is only known in hindsight.

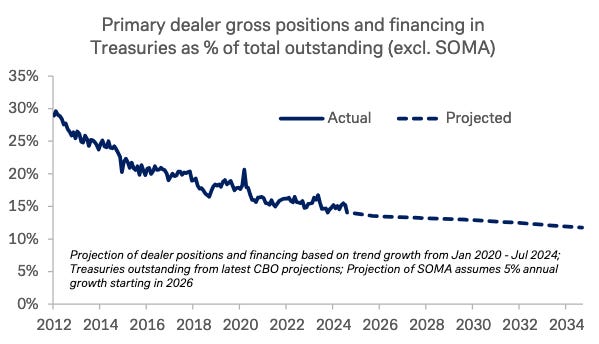

This chart comes from a presentation on financial resilience released October 29, 2024, by the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC). It shows the share of Treasuries held by the banking system declining, nearing the Lower Comfort Level of Reserves (LCLoR). This poses a problem because, as the Fed conducts quantitative tightening (QT) and surplus nations’ central banks sell or stop reinvesting net export earnings (i.e., de-dollarization), marginal buyers of Treasuries become unstable bond-trading hedge funds.

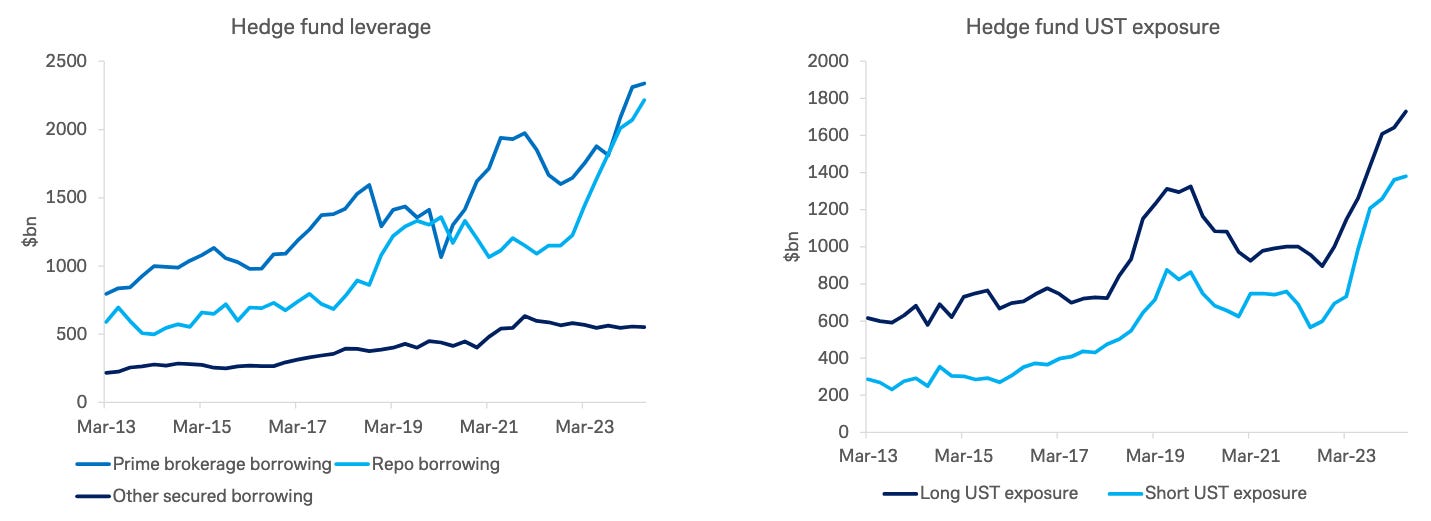

This is another chart from the same presentation. It shows hedge funds filling the gap left by banks. However, hedge funds aren’t genuine buyers of funds. They profit via arbitrage trades—buying cheap cash Treasuries while shorting Treasury futures. The cash leg is financed via repo markets. Repo transactions involve exchanging assets (like T-bills) for cash over a period at an interest rate. Repo pricing depends on available balance sheet capacity at commercial banks. As balance sheet capacity shrinks, repo rates rise. If Treasury funding costs increase, hedge funds can only buy more when cash Treasuries are cheap relative to futures. This means Treasury auction prices must fall and yields rise—contradicting the Treasury’s goal of issuing more debt at lower cost.

Due to regulatory constraints, banks can’t buy enough Treasuries or finance hedge fund purchases at reasonable rates. Therefore, the Fed needs to once again exempt banks from SLR. This would improve Treasury market liquidity and allow infinite QE to be directed toward productive areas of the U.S. economy.

If you’re still unsure whether the Treasury and Fed recognize the importance of loosening bank regulations, TBAC explicitly calls for it on slide 29 of the same presentation.

Tracking Indicators

If Trump-o-nomics operates as I’ve described, we must monitor the potential for bank credit growth. From earlier examples, we learned that QE for the rich increases bank reserves, while QE for the poor increases bank deposits. Fortunately, the Fed publishes both data points weekly for the entire banking system.

I’ve created a custom Bloomie Index combining reserves and other deposits & liabilities <BANKUS U Index>. This is my custom metric for tracking the quantity of U.S. bank credit. In my view, it’s the most important money supply indicator. As you can see, sometimes it leads Bitcoin—for example in 2020—and sometimes lags, as in 2024.

More importantly, consider asset performance when bank credit supply contracts. Bitcoin (white), S&P 500 (gold), and gold (green) are all adjusted by my bank credit index. Values normalized to 100 reveal Bitcoin’s standout performance—up over 400% since 2020. If you can take only one action to hedge against fiat depreciation, it’s investing in Bitcoin. The math is indisputable.

What Lies Ahead

Trump and his economic team have made clear they will pursue a weaker dollar and provide necessary funding to support U.S. industrial reshoring. With Republicans controlling all three branches of government over the next two years, they can advance Trump’s entire economic agenda unimpeded. I believe Democrats will also join this “money-printing party,” as no politician can resist the temptation to hand out benefits to voters.

Republicans will lead with a series of bills encouraging domestic expansion by manufacturers of critical goods and materials. These bills will resemble Biden-era legislation like the CHIPS Act, Infrastructure Act, and Green New Deal. As firms accept government subsidies and secure loans, bank credit will surge. For skilled stock pickers, consider investing in public companies producing government-prioritized goods.

Eventually, the Fed may loosen policy—at minimum, exempting Treasuries and central bank reserves from SLR (supplementary leverage ratio). At that point, the path to infinite QE will be wide open.

The combination of legislatively driven industrial policy and SLR exemption will trigger an explosion in bank credit. I’ve shown that the velocity of money under this policy far exceeds traditional Fed-led QE for the rich. Therefore, we can expect Bitcoin and crypto assets to perform at least as well as they did from March 2020 to November 2021—or even better. The real question is: how much credit will be created?

COVID stimulus injected about $4 trillion in credit. This time, the scale will be far larger. Defense and healthcare spending are already growing faster than nominal GDP. As the U.S. increases defense spending to counter a multipolar geopolitical landscape, these expenditures will accelerate. By 2030, the share of Americans aged 65+ will peak, meaning healthcare spending will grow rapidly from now until then. No politician dares cut defense or healthcare spending—they’d be swiftly voted out. All this means the Treasury will continuously inject debt into markets just to keep functioning. I’ve previously shown that QE combined with Treasury borrowing has a money velocity greater than 1. This deficit spending will boost America’s nominal growth potential.

The cost of bringing U.S. firms back home will reach several trillion dollars. Since 2001, when America allowed China into the WTO, the U.S. voluntarily shifted its manufacturing base to China. In less than three decades, China became the world’s factory—producing high-quality goods at the lowest cost. Even companies attempting to diversify supply chains beyond China, supposedly to cheaper countries, find the deep integration among countless suppliers along China’s east coast highly efficient. Even if labor is cheaper in Vietnam, they still need to import intermediate goods from China to complete production. Therefore, relocating supply chains back to the U.S. will be a monumental task. If done for political necessity, the cost will be extremely high. I mean providing trillions in cheap bank financing to move production capacity from China to the U.S.

Reducing the debt-to-nominal-GDP ratio from 132% to 115% required $4 trillion. Suppose the U.S. wants to further reduce this ratio to 70%—the level of September 2008. Linear extrapolation suggests $10.5 trillion in new credit would be needed to achieve this deleveraging. This is why Bitcoin’s price could reach $1 million—because prices are set at the margin. As Bitcoin’s circulating supply dwindles, vast amounts of global fiat money will compete for safe-haven assets—not just from the U.S., but also from China, Japan, and Western Europe. Buy and hold. If you doubt my analysis of poor-man’s QE, simply revisit China’s economic development over the past thirty years—and you’ll understand why I call the new Pax Americana economic system “American capitalism with Chinese characteristics.”

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News