From Likes to Tokens: The Financialized Future of Web3 Social Networks

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

From Likes to Tokens: The Financialized Future of Web3 Social Networks

Meme coins could be a prelude to the future form of the internet.

Author: Joel John

Translation: TechFlow

Note: Although I rarely mention our portfolio companies in this newsletter, today I'm making an exception for two of them. We've been deeply exploring decentralized networks long before the term "Web3" existed, and have had the privilege of working with some of the industry's top talent. Today’s article is almost like an invitation to startups building consumer-facing technologies on blockchain infrastructure. We will continue learning from, investing in, and growing alongside entrepreneurs who are shaping the new internet.

In short: Blockchains enable capital to move at the speed of data, while allowing economic interactions among participants to be fragmented and scaled in ways traditional fintech companies cannot achieve. We have yet to fully grasp the profound implications of this phenomenon on human interaction.

When capital formation and speculation merge with attention markets, human behavior changes. Polymarket and PumpFun are early prototypes of the next-generation social networks. The next major trading platform may well be a social network—and the next major social network might become a trading platform.

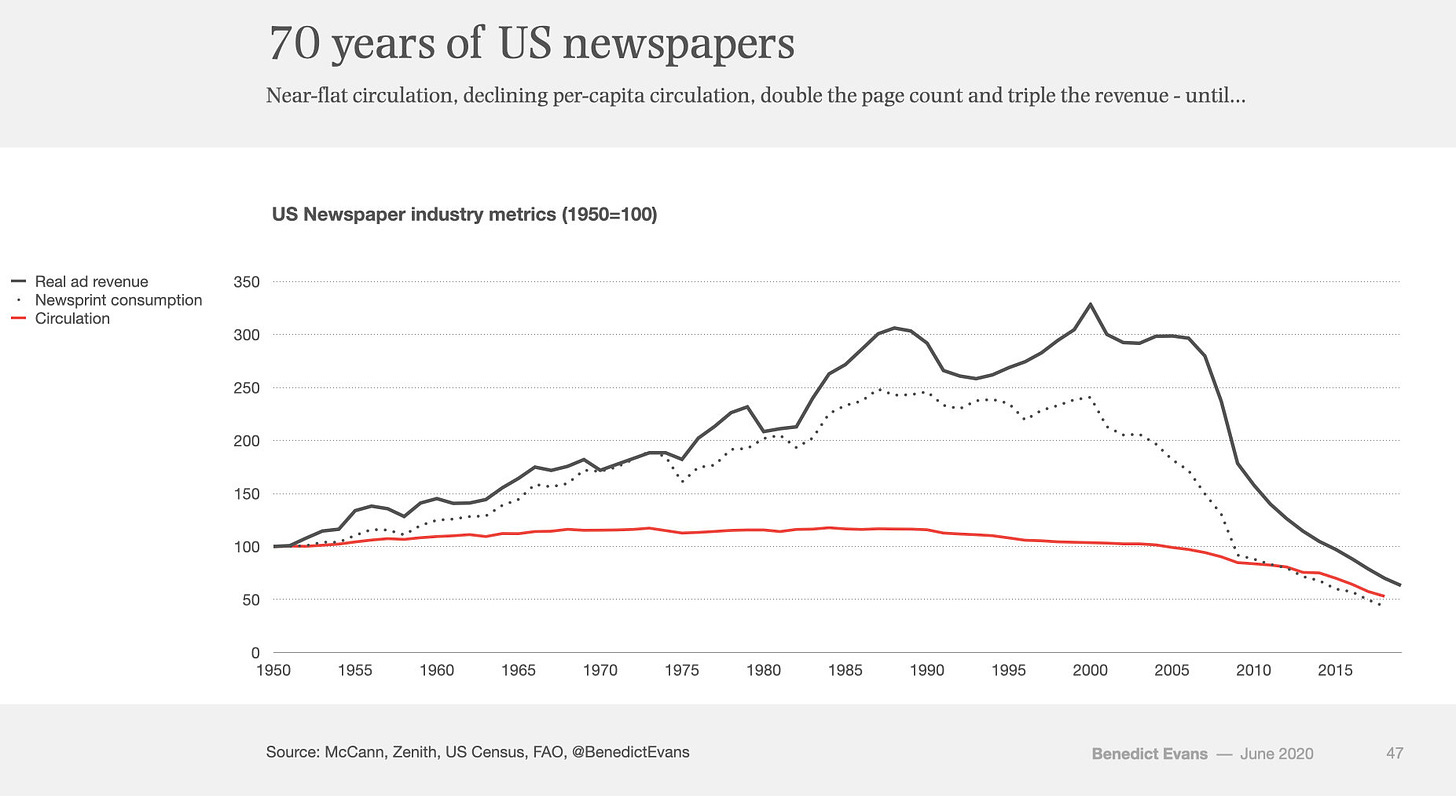

This chart by Ben Evans is one of my favorites. It shows how newspaper revenues changed around 1995, when the “information superhighway” first emerged.

Take a look at Ben Evans’ chart. Published in 2019, it highlights newspaper revenue trends up to that year. Newspapers were once part of our morning routine—a traditional human institution. Today, we’ve replaced them with endless scrolling and memes. In this era of clicks above all, the relevance of a story no longer matters—only the emotional response it triggers. That’s why Elon Musk acquired X, not The Washington Post like his billionaire peer Jeff Bezos.

Media in the 21st century has become click-driven. We’ve created a parallel world where attention is commodified, quantified, and sold like pastries in a bakery. But this time, what’s being shaped isn’t flour—it’s human thought, and like most markets, it comes at a cost. Ben Evans’ chart merely illustrates a downward trend; Kyle Chayka’s *The Filterworld* reveals the deeper cultural and societal impact of this shift.

As the web evolved, so did our definition of a “good story.” We no longer care about informational relevance—we care about virality. Worse still, we measure stories by how much emotion they provoke. As a result, local journalists covering neighborhood charities or foreign correspondents exposing hidden crises have faded into irrelevance.

We now prefer to fill our feeds with cats, dogs, and 30-second political clips edited for maximum outrage.

Modern social networks operate this way because they are, at their core, trading platforms. In the early 2010s, many people who might have pursued quantitative finance on Wall Street instead joined emerging social networks like Facebook after the 2008 financial crisis. This talent pool proceeded to slice, package, and sell human attention to the highest bidder. In doing so, social networks became trading platforms—and these platforms captured most of the value.

Neither creators nor users benefit meaningfully. While Twitter is experimenting with sharing ad revenue with top creators—an approach that may prove viable—it’s also tearing apart democratic discourse and making Sunday dinners unbearable. Is there another way?

We believe there is. Qiao Liang from Degencast collaborated with us on this piece. Over the past year, he has been building Web3 social infrastructure and offers some thought-provoking insights. At its heart, the argument is simple: blockchains are tools for value transfer.

As blockchains mature, money will flow at the same speed and frequency as other data. In such an environment, can social networks reinvent their business models? Let’s explore.

Incentive Networks

Last weekend, multiple AI-related tokens launched—think large language models (LLMs) plugged into the Twitter API. The largest, $GOAT, reached a $400 million market cap, while most startup founders struggle to justify a $10 million valuation. What drives such capital flows? Why do people invest thousands of dollars into these assets?

A simple explanation is that meme markets are fast implementations of the “greater fool theory.” People buy, hoping to sell later at a higher price. Owning one token doesn’t make you any less of a GOAT community member than owning 10,000. But people increase holdings because these narratives find their own paths to virality, attracting attention. Consider that Matt Levine—one of my favorite writers—wrote about WIF and GOAT in his Bloomberg newsletter. Early-stage startups rarely get that kind of media exposure.

Regardless of the asset, memes create networks that incentivize both attention and capital. These resemble social networks—they are gathering places for humans in the internet age. But their incentives aren’t based on trolling or meaningful discussion; they’re rooted in capital formation and speculation. As long as new users keep flowing in, participants profit. In extreme cases, meme assets without a Lindy effect like Doge may be closer to Ponzi schemes than social games.

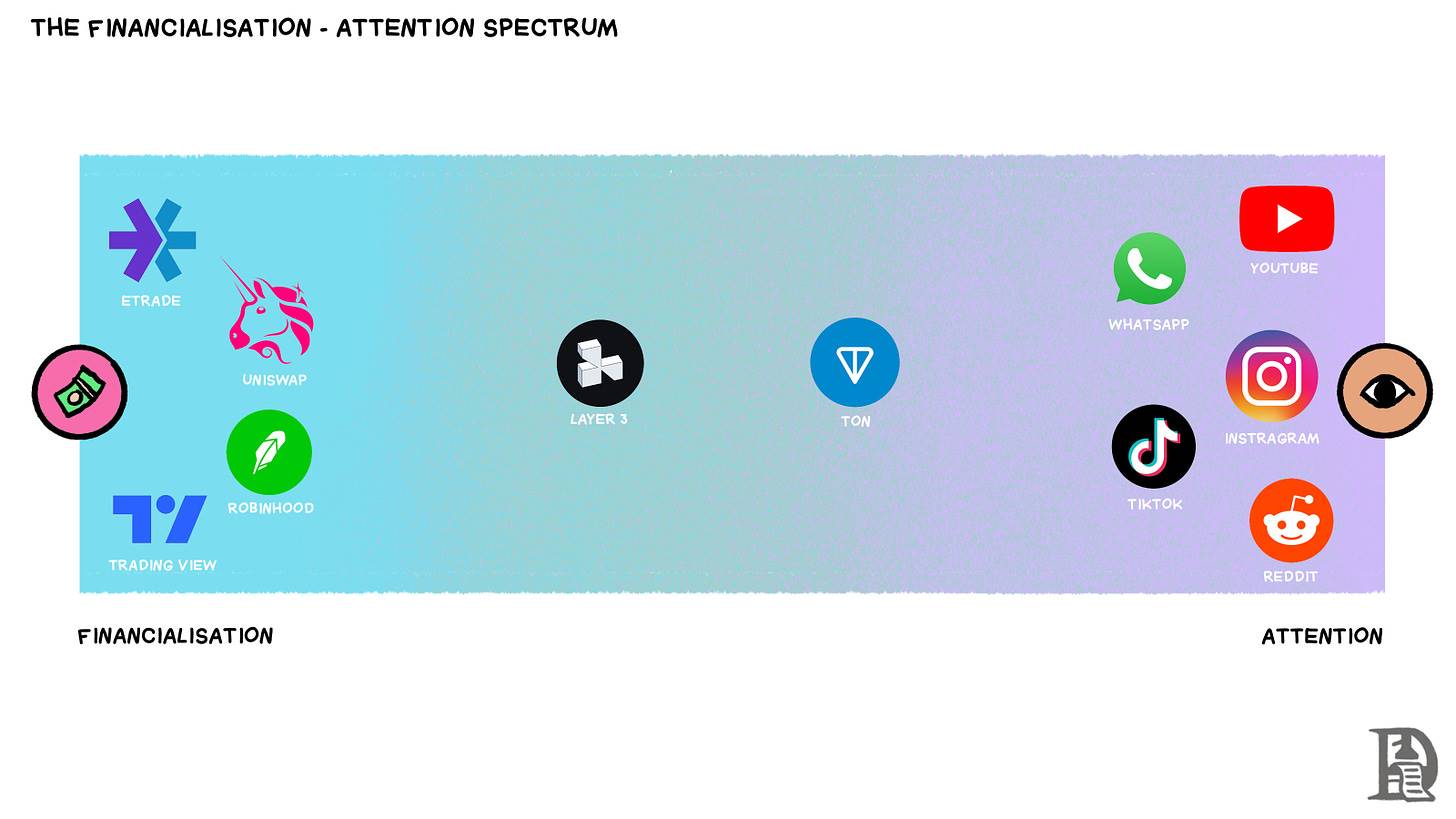

The internet operates along a spectrum of attention and financialization. When you use Twitter, you're on the attention end. Users consume TikTok videos, spending attention for dopamine hits. Cryptocurrencies represent the opposite end. When Reddit users gathered around Gamestop, their motivation was financial gain. At the extreme, platforms like PumpFun attract users for tokens and retain them through token-driven social interactions. Fundamentally, both are mechanisms for attracting and retaining users—either through dopamine-inducing content or financial returns.

This is exactly what I tried to emphasize in a post last year: how volatility can drive product adoption.

Back then, I didn’t fully grasp how capital could be used to build entirely new social networks. Farcaster and its signature meme asset Degen launched months later. In Farcaster’s early days, user onboarding was highly personalized. Dan Romero famously held calls with potential users and personally invited them. These early adopters—mostly crypto founders and developers—formed the initial social graph that powered Farcaster’s early growth. Then came Degen.

Degen introduced a tipping system that allowed community members to reward those adding value to the ecosystem. As of this writing, nearly 10 million transactions have occurred on Degen, with around 784,000 wallets holding the asset. Degen decoupled the social network (Farcaster) from its financial incentives. Suddenly, a creator making meaningful contributions could receive substantial monetary rewards.

In the following months, numerous Farcaster communities launched their own tokens. While many of these tokens have since lost value, this blurring of financialization and attention signals a broader shift. If Reddit launched in 2024, it might use a base token (like RDIT) and millions of sub-tokens distributed to subreddit moderators. Token value could be driven by membership size and depth of meaningful engagement within each sub-community.

But that’s not how Farcaster works. As a user, I stopped using the platform when content quality declined. And time spent between Twitter and Farcaster was already limited.

We’ve seen early attempts at this attention-incentivized model—like T2 World, where user tokens are staked proportionally to their engagement with content. But why does this matter? History from Web3 protocols offers clues. Ethereum’s early developers could keep contributing and building because they held ETH. This new wealth spawned a generation of entrepreneurs. Over the past two years, contributors to on-chain communities haven’t had the same opportunity.

We briefly glimpsed this alternative world during the NFT boom (creator royalties) and on Farcaster (Degen tips), but neither proved sustainable.

There are two reasons. For such communities to endure, they need continuity and relevance. Bored Apes are an interesting subculture, but their game quality or IP distribution struggles to find meaningful relevance. The strength of algorithmic platforms lies in their ability to constantly surface new content and maintain user engagement.

Meme markets are increasingly becoming speculative plays around trending events—short-term games purely for profit.

Today, the closest examples are prediction markets and meme tokens. PumpFun often inspires pet names, as people rush to launch tokens tied to them. Similarly, Polymarket is becoming the go-to platform for tracking market sentiment on event outcomes. In fact, if you examine markets like the U.S. presidential election, you’ll see users’ views closely aligned with their financial bets—offering insight into their underlying motivations.

Polymarket and PumpFun have already processed tens of billions in transaction volume. Last week, Polymarket briefly topped the app store charts. We’ve crossed the chasm. Now may be the moment consumers start asking, “What apps are worth my time?” To build these, we need sufficiently financialized social networks. In our view, such networks will be built on several core principles.

Sufficient Financialization

You can't design a social network to do everything. Varun Sreenivasan, in a piece titled *Sufficient Decentralisation for Social Networks*, argues that expecting every user to run their own server isn’t a scalable path. He outlines trade-offs that allow for sufficient decentralization without compromising user preferences.

What the internet has always lacked is fast, low-cost, bidirectional micro-value transfer. When you see an ad on Instagram, that’s unidirectional value transfer—you exchange attention for content. But if we treat social networks as starting points of attention economies, we must remember they emerged before Stripe existed. If Craigslist was the beginning, banks weren’t even online yet. Since then, our toolkit has evolved dramatically.

Farcaster Frames and Solana Blinks show what happens when bidirectional value moves on-chain. Users can mint NFTs directly from their Farcaster feed. This allows users to be tagged on-chain and rewarded via future airdrops. Take our publishing outfit: I’m frustrated we lack an on-chain graph tracking users who consume our content. In a Farcaster-powered world, each newsletter could embed links allowing readers to “collect” each issue and earn an NFT upon reading.

Why does this matter? Two perspectives:

-

A top-down approach: Whenever a brand wants to engage our audience, we could simply require them to incentivize our on-chain user base. In this model, we align incentives with active users.

-

A community-driven growth model: Over time, as publishers, we may become unnecessary—the community grows on its own. We simply serve as hubs where ideas gather, discuss, and collaborate.

In the second model, dependency on individual creators diminishes. Platforms like FriendTech face challenges because their financial outcomes depend heavily on the creators who mint handles. If a creator disengages or loses interest, the community bears the cost. Ironically, in FriendTech’s case, the founders themselves chose to walk away. In such scenarios, building more robust, resilient community tools becomes critical.

Another reason independent creators shouldn’t be tradable assets is that they’re human. Linking their value to market prices and enabling trading is unethical—it imposes pressure creators may not want. Imagine Van Gogh during his depression as a tradable asset. Would we bet on Nikola Tesla during his manic episodes? A person’s economic value at any moment reflects only their state at that instant. Humans are bundles of potential, unfolding over time. Adding speculation doesn’t enhance creativity.

In this sense, communities resemble nations, and individuals are citizens. A strong community withstands market pressures even when individual members struggle. Perhaps this is why human civilization has long relied on tribes. Anyway, I digress.

If communities truly are the best vehicles for capital formation and trading, what foundational elements today suggest this possibility? Most communities emerging as social networks will be niche, defined by quantifiable metrics for ranking and status. These will be consumer apps with little resemblance to the extreme speculation seen on Pump. The best example today is Receipts.

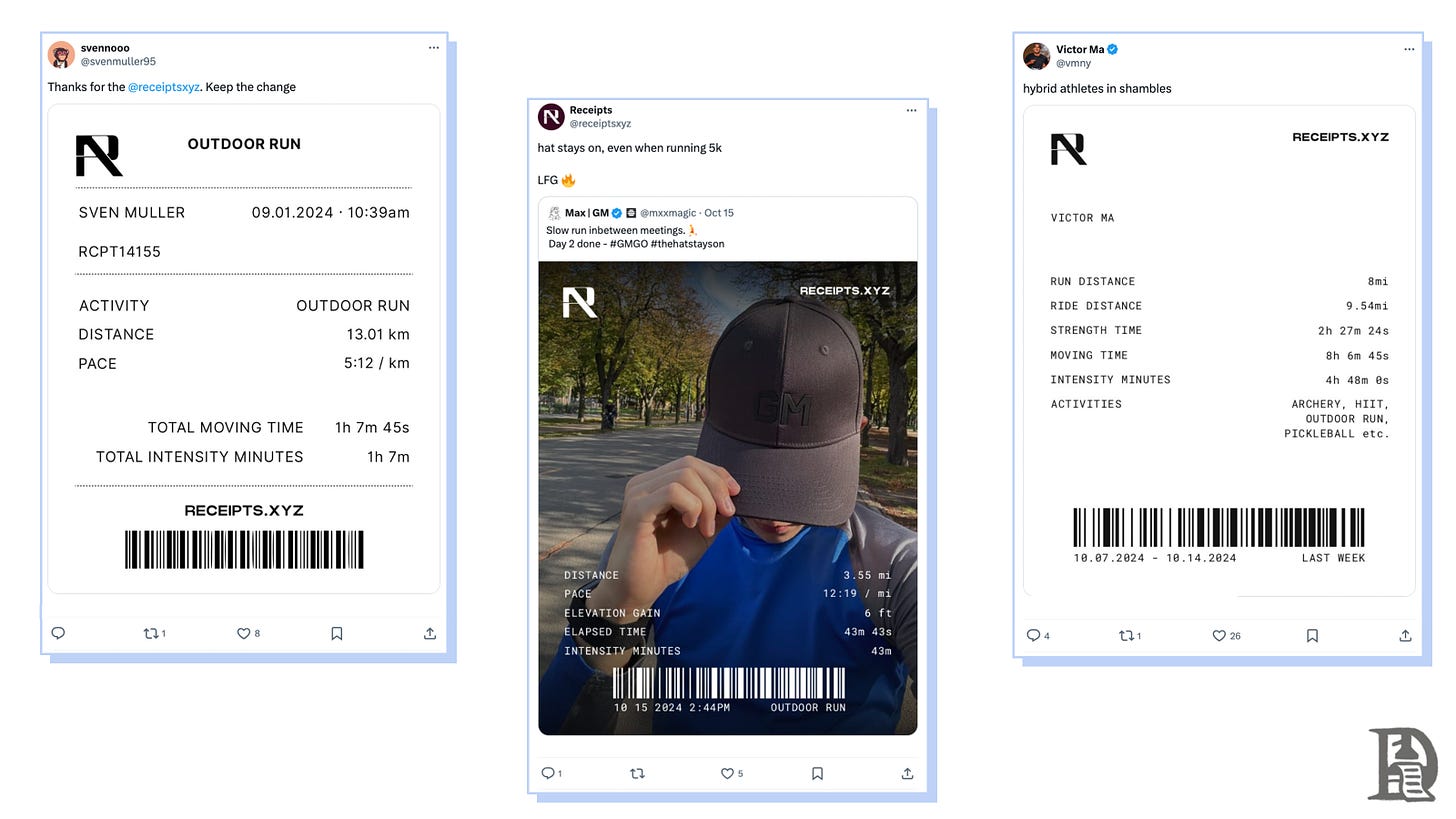

Receipts users share their workout results on Twitter

Receipts pulls data from fitness trackers like Apple Watch or Garmin to issue points. Users frequently post their workout “receipts” on Twitter for reputation and community recognition. If users connect their Farcaster accounts, they can rank based on “intensity minutes”—periods when their heart rate spikes during exercise. These receipts are issued on-chain, and intriguingly, about 2,100 are currently listed for sale on OpenSea. Why does this matter?

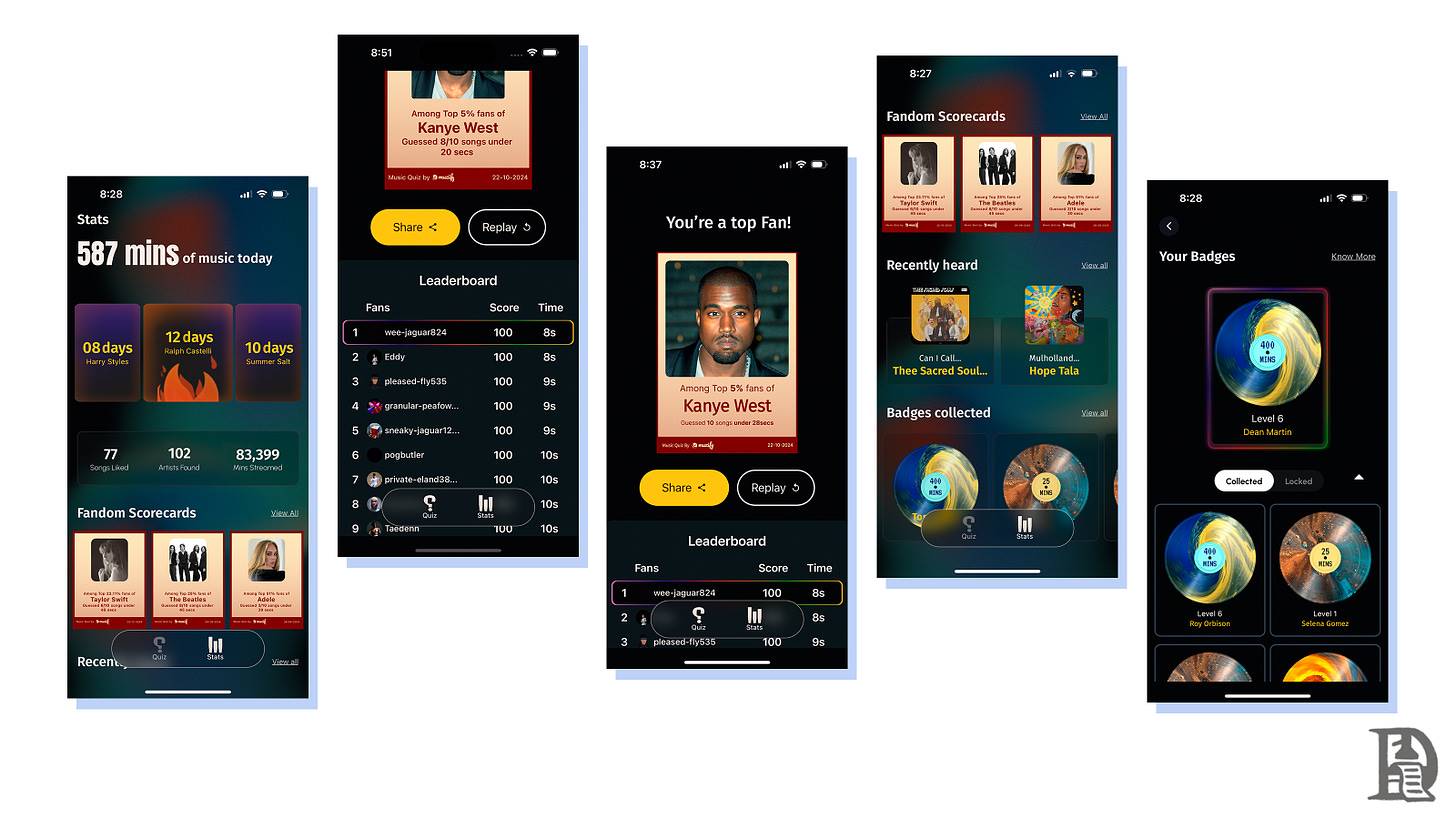

Muzify ranks users based on individual artist listening time.

It creates an on-chain music enthusiast graph. At one of our portfolio companies, we’ve seen a similar music app. Muzify lets users connect their Spotify accounts and see their ranking for how frequently they play certain artists. In recent months, nearly a million users have adopted the product. As more join, Muzify could leverage this “verified” fan graph to offer free concert tickets or early access to indie artists who typically know little about their most loyal fans.

Nameet, Muzify’s founder, shared two interesting observations. First, Kanye West is the most-played artist among users—unsurprising. Second, users’ real “flex” lies in discovering obscure artists. They love showcasing knowledge of niche musicians to signal taste.

One of our readers, Jaimin, is building a similar product. It helps users “check in” via browser extensions on niche websites. So if you joined a site early (like Google in 1998) and it later exploded, you’d have a timestamped credential on-chain, stored in your wallet as proof. What’s the use? Right now, none. It just shows a user’s ability to spot trends and discover sites before they go viral.

For such niche social networks to grow, they need to reach a critical mass of users. Currently, Receipts and Muzify focus on optimizing UX. Over time, platforms only truly evolve when user interactions increase—eventually becoming full-fledged social networks.

So how do we maximize financial upside in such cases? What are their business models? Will they simply bundle and sell user data to the highest bidder, like existing models? Probably not. To scale, such businesses need three core components:

-

Asset issuance: Users contributing to Web3 social networks should receive assets as rewards. Receipts and Muzify currently use NFTs. In the future, these might be points redeemable for tokens.

-

Context and trading: An asset without utility becomes irrelevant over time. Polymarket succeeds because its tokens reflect real-world topic attention. Same with PumpFun.

-

Coordination: Of the 2.5 million tokens launched on Pump, fewer than five now have market caps over $100 million. Most exist only for volatility games. But when assets align with real communities requiring on-chain coordination (via DAOs), we see greater value emerge on both tokens and their platforms.

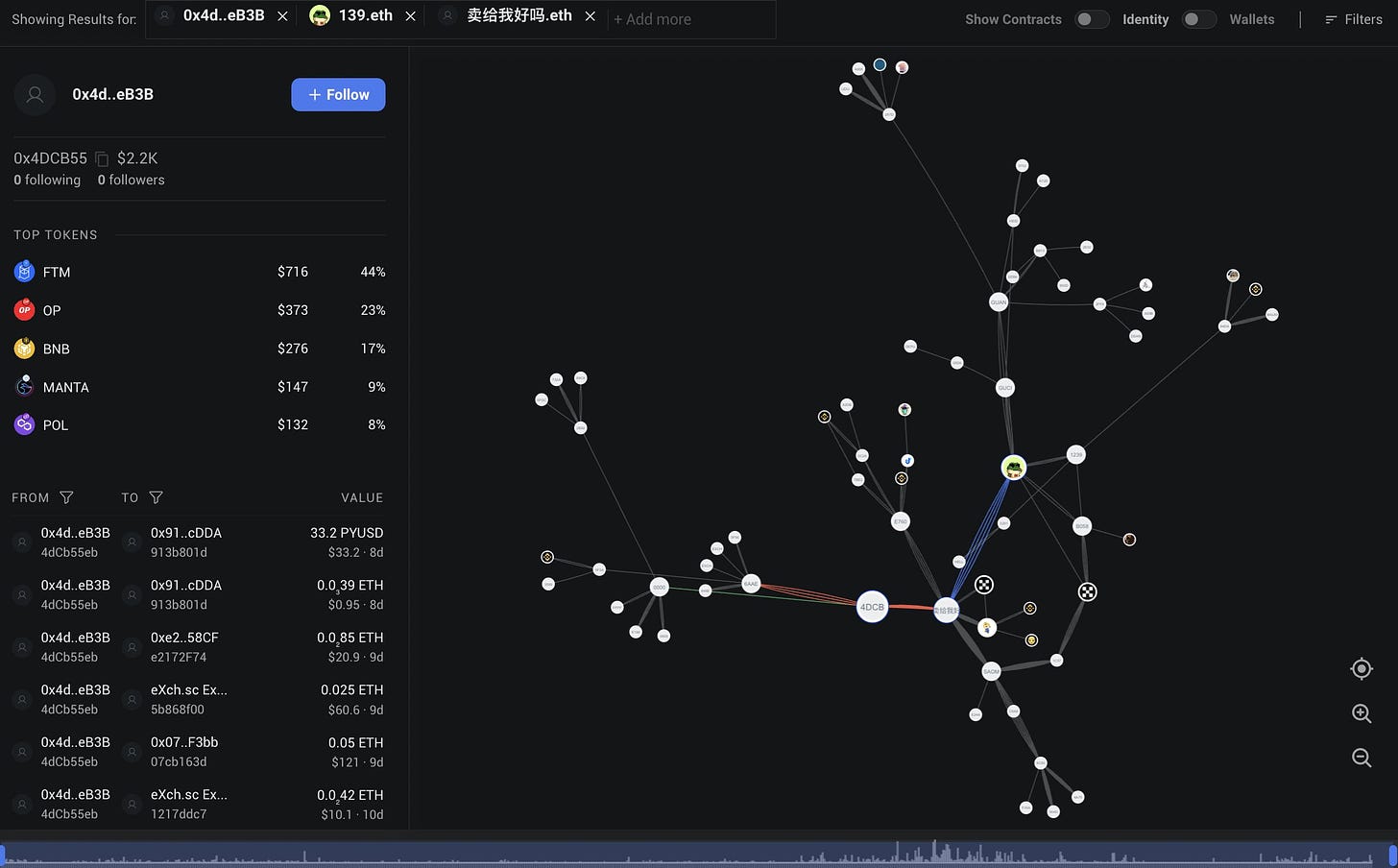

A useful mental model: blockchain networks are dynamic components of social networks. On-chain events—price movements, mass asset transfers—can form the foundation of social interactions. It’s like what might happen if Venmo became a social network, except here the transaction stream is global and far more engaging. One of our portfolio companies (0xPPL) is building precisely on this idea.

0xPPL helps users discover wallet relationships and delivers social trading experiences based on them. Image from their Twitter. Blockchain can also financialize existing social networks. Telegram, with nearly 800 million monthly active users, is monetizing via the TON network. According to TONStat, about 23 million wallets exist on the network. Why does this matter? TON’s highly concentrated retail user base makes it a powerful distribution channel for emerging apps.

Multiple chat groups already active on Telegram enable social-financial interactions. In fact, Telegram’s adoption of TON may be the clearest example we’ve seen of “sufficient financialization.”

The Telegram app remains centralized, while TON functions as a global value transfer layer. As of May 2024, Telegram is experimenting with sharing ad revenue and sticker pack sales with creators. Here, crypto isn’t used for open access or user ownership—but for monetization.

Looking Ahead

Studying the nature of social networks reveals that existing ones aren’t disrupted by better alternatives. Instead, they’re replaced by products that are functionally similar but fundamentally different. TikTok isn’t a better Instagram, Instagram isn’t a better Twitter, and Twitter wasn’t a better AOL chat room. The grammar is off, but you get the point. The future of Web3 social networks won’t be a better Twitter—it will lean into what the space already excels at: speculation, verifiable rankings (influence), and ownership.

From this lens, the next major social network may resemble an exchange. Today, when Binance lists an asset, tens of millions of users instantly pay attention. The next big social network might spotlight where users gather and trade. Moonshot and Pumpfun are early examples. Structurally, though, they don’t solve the incentive or media issues plaguing Web2 social networks.

Web3-native memes (like Goat) already spread widely on traditional platforms like Twitter. When LLM-driven accounts post, users quickly retweet, amplifying narratives due to financial incentives. What if we applied this to community-created content? Would users propagate stories better? Could a community-owned local paper survive? We don’t have answers yet. But one thing is clear.

Rather than everyone having “15 minutes of fame,” assets now temporarily reach $100 million FDVs due to attention. Studying meme assets like Moo Deng shows this phenomenon persists. But how do we move beyond pure speculation?

The history of network evolution is one of bundling and unbundling. Niche products like Receipts and Muzify are currently standalone apps with no user interaction. But as users realize assets (NFTs or tokens) can interoperate across protocols (Base), this could change. We’ll see interfaces combining on-chain primitives with information feeds, enabling users to discuss, own, and coordinate around topics that matter. Products that succeed here could become the next big social networks. Web2 social networks commodified our attention and sold it to advertisers.

Blockchain-powered social networks could return agency to users through finer-grained mechanisms, letting them capture, trade, and benefit from the value they create.

What would that look like? Joseph Eagan from Anagram once shared an insightful analogy. The 2021 Gamestop event on Reddit offered clues. Users gathered to fight hedge fund shorting. Trade discussions happened on Reddit; trades themselves occurred on platforms like Robinhood. If we assume more of the world’s assets will be tokenized and moved on-chain, a Web3-native social network could help users

(i) execute trades,

(ii) share a portion of profits with the platform, and

(iii) reward trade initiators and community moderators.

But this didn’t happen. Instead, platforms like Robinhood captured most of the value—and risk.

Can Web3 social networks revive newspapers? Probably not. I think we’ve moved past traditional media. Perhaps we’re entering a new phase where community members own, curate, and monetize content—without relying on advertisers. Substack is a preview of this future. Ironically, it’s built on fintech infrastructure, which limits creators’ ability to transfer ownership to their audiences.

If markets (like Polymarket) are seen as ultimate truth-seeking mechanisms, combining financial incentives with communities might be a superior monetization model compared to attention economies. Meme coins could be preludes to future network forms. We’re stress-testing foundational features that could power what’s next. This process sometimes resembles mania—even absurdity.

Yet, viewed from a broader perspective, the building blocks we need for the future already exist today.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News