When memes become means of production, opportunities for wealth creation become more open and transparent.

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

When memes become means of production, opportunities for wealth creation become more open and transparent.

Part of the appeal of memecoins lies in their ability to offer wealth creation as an entertainment product, providing fair and accessible participation opportunities.

Author: Simon de la Rouviere

Translation: TechFlow

The reason I consider myself a socialist, in a sense, is that I want more people within society to possess greater wealth. This isn't merely about a welfare state supported by taxation for public services, but something closer to classical socialism: enabling more people to directly own the "means of production." Capitalism works best when more individuals own capital.

In the cryptocurrency space, internet memes have become a significant market force since Dogecoin emerged in 2013. As blockchain scalability and user experience improved, launching any token became easier than ever before. Since 2021, this trend has surged again, with market value exceeding $50 billion.

To some, cryptocurrencies are already difficult to grasp—let alone memecoins. From an outsider's perspective, it may appear to be a zero-sum gambling game filled with scams promising high returns, ultimately just extracting money from investors. While such cases do exist, there are also many who willingly participate in this financial contest. If you dig deeper into why, you might uncover lessons that could inform improvements to modern economic systems. Sometimes, solutions require unique perspectives.

-

Community culture. Memecoins aren't just investments—they're more like entertainment, full of fun and excitement. By purchasing memecoins, people can easily join a social community.

-

Increased fairness. Over time, opportunities for wealth creation have become fairer. While this communal vibe doesn't appeal to everyone (after all, trading animal-themed derivatives or politically charged 4chan-style memecoins lacks broad appeal), the aspect of fairness highlights flaws in our current wealth-creation structure. Many successful memecoins are perceived as “fairly launched,” avoiding scenarios where only a few get rich. They typically lack centralized leadership, and rules are enforced via transparent, verifiable smart contracts—reducing the risk of investors being “rugged.”

Thus, part of the appeal of memecoins lies in offering wealth creation as an entertainment product—with fair and accessible participation. If a memecoin launch is fair (no dominant group) and faces minimal regulation, it means anyone, regardless of location or identity, can take part. Once involved, whether you're a wealthy fashion designer in Manhattan or a subsistence farmer in the Philippines, your opportunity is equal.

Yet in reality, most forms of wealth creation today are accessible only to the rich, with entry barriers rising ever higher. Access to liquidity is harder to obtain, certain rules favor the wealthy, and public access to markets continues to shrink.

Liquidity Issues

Not everyone enjoys abundant liquidity. For example, starting a tech company in South Africa is far more difficult than in the U.S., where significantly more capital is available for new ideas. Starting a business is inherently tough, and growing compliance requirements make it even harder.

Access Inequality

Even within the U.S., lack of funds can exclude you from investment opportunities. In some cases, companies selling securities allow only the wealthy to invest. For instance, under Rule 506(c) of Regulation D of the Securities Act, if you publicly advertise a private investment, only accredited investors may participate. If you lack sufficient wealth, too bad. Essentially, such rules exclude people—even if they're deemed necessary for maintaining an "orderly market."

Public Market Investing

Suppose you're not qualified as an accredited investor. What avenues remain for participating in wealth creation? In the U.S., aside from limited private opportunities, your main options are public markets—such as direct stock ownership, ETFs, and bonds. While companies may deliver solid returns after going public, most substantial gains actually occur before IPO.

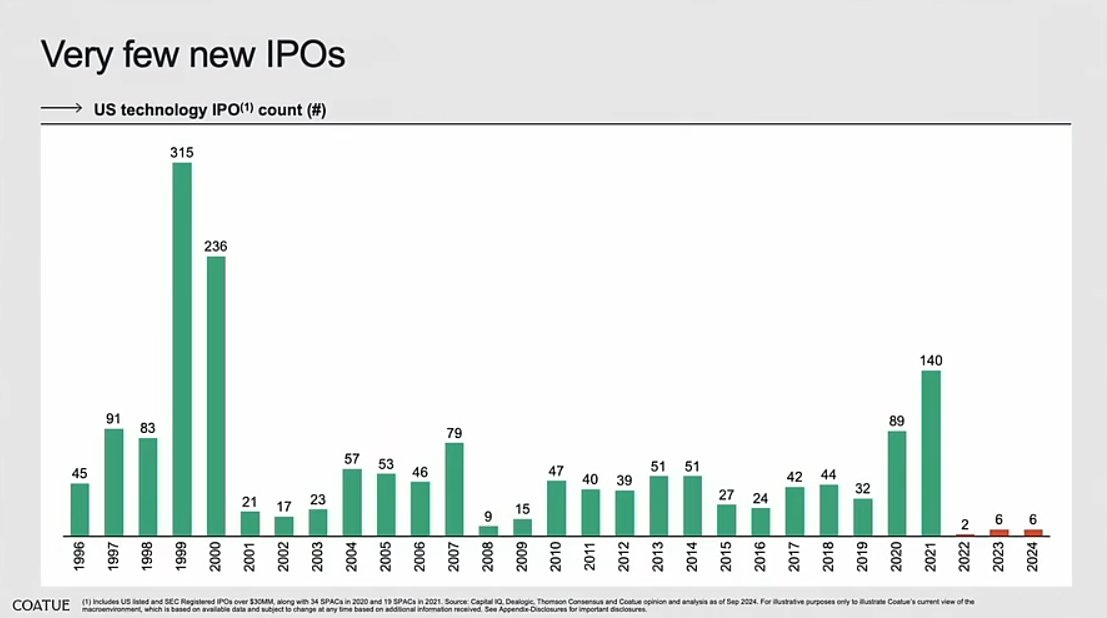

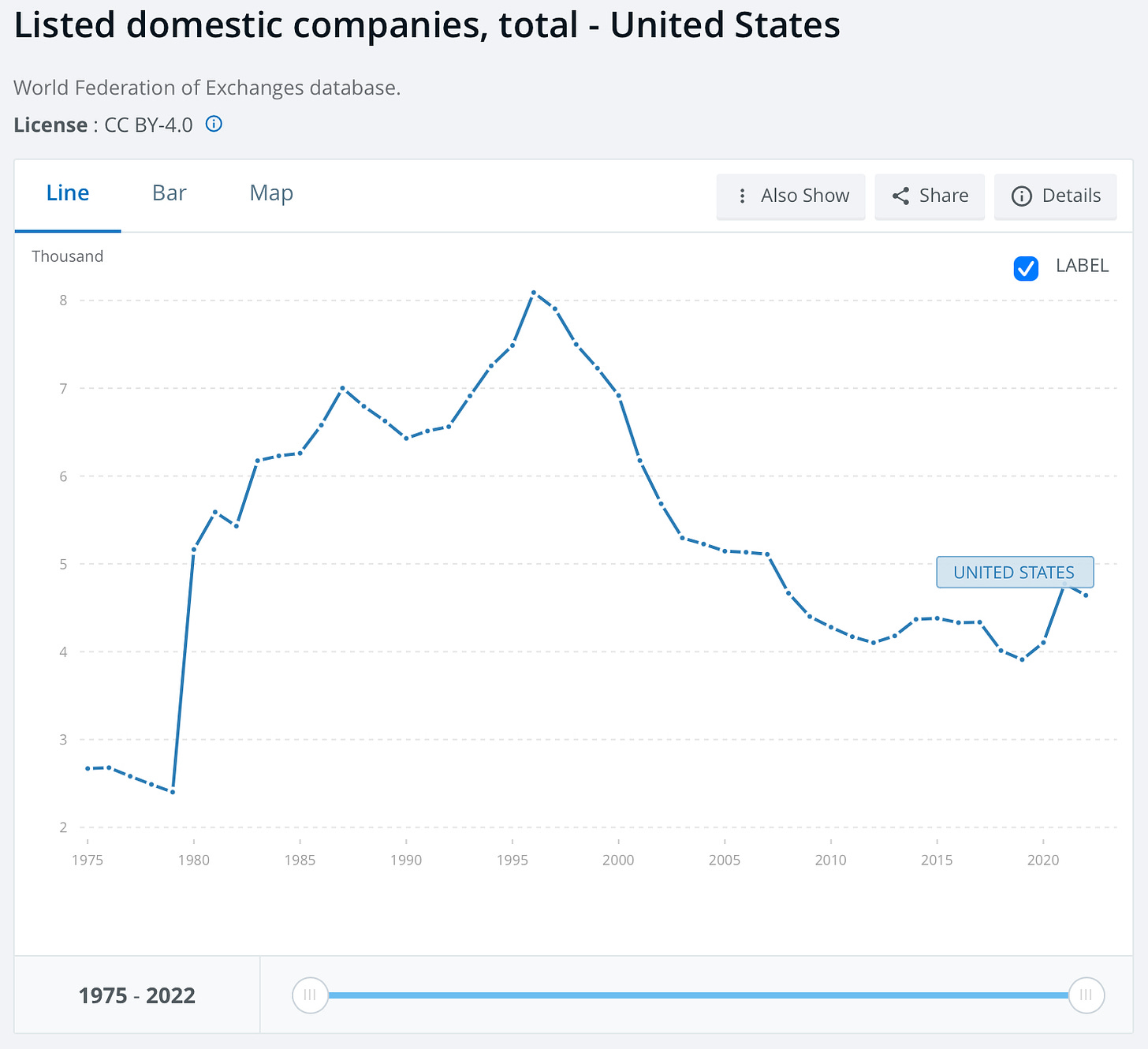

However, IPO costs in the U.S. are extremely high, and enthusiasm has waned since 2022. In 2019 alone, legal and accounting fees averaged over $2 million. The number of IPOs in the U.S. has been declining.

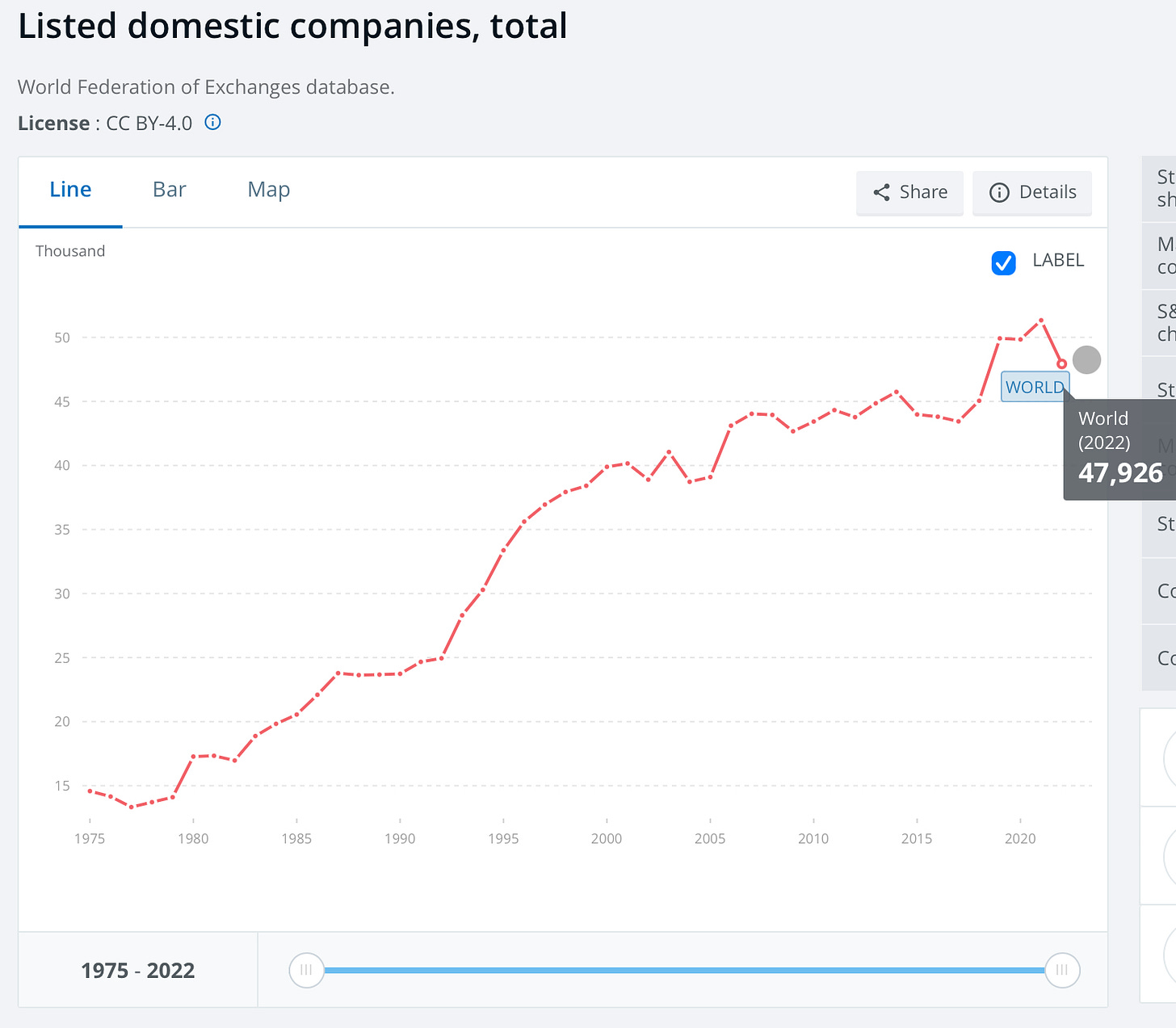

Globally, the total number of listed companies also paints a bleak picture. I attempted to gather worldwide data, but found an anomalous spike in China’s figures from World Bank data, which I couldn’t verify. Thus, unverified global estimates look roughly like this:

More specifically, here's what the U.S. looks like:

Globally, while industrialization in other regions has increased per capita investment opportunities in some areas, growth has stagnated in developed countries like the U.S. Will this trend continue as more nations reach industrial parity, or will it become the norm?

So, how should we respond?

Faced with these challenges, many might lean toward deregulation—but trade-offs must be weighed. Financial regulations were originally designed to ensure orderly markets, protect investors, and maintain a relatively healthy investment environment. While adding compliance layers reduces risk, it also means capital flows to places where investors feel safer—even if it excludes many from participating.

Full-scale deregulation might increase ownership access in some ways, but could also undermine many well-intentioned efforts to generate wealth.

Hence, the solution isn’t necessarily simple deregulation, but rethinking how to effectively protect investors in modern society. Many existing safeguards were designed before the internet era—like concerns over bearer stock certificate fraud. So, if we want to offer reasonable protection without excessive barriers, how should society achieve this today?

One area worth watching is memecoins. Within their financial games, standout projects show we can rethink early access to wealth creation—and provide appropriate investor protection through different mechanisms. This means:

-

Protect investors not by exclusion, but by innovative methods that provide certainty.

-

Ensure transparency without relying on costly, burdensome administrative compliance and paperwork—instead use code that prevents misconduct.

-

Maintain market order through systemic design, rather than focusing solely on individual impacts.

For example, many recently popular memecoins employ token bonding curves—a mechanism I helped promote. It starts by establishing a reserve, then transparently allows participants to buy and sell along a price curve, creating new supply. This ensures funds don’t go to any single entity, but serve one purpose: liquidity. When a threshold is reached, supply caps, and reserve funds move to an automated market maker, ensuring ample market liquidity.

This means:

-

Investors don’t need to worry about funds being stolen.

-

No insider advantages—everyone participates equally (similar to open markets, dependent only on timing).

-

Early guaranteed liquidity reduces manipulation risks.

-

All processes are transparent and public.

In many cases, this model enables earlier and fairer participation while offering some protection to small investors. While it can’t eliminate scams entirely, it exemplifies shifting where protections are applied.

Yes, this sounds great—but should everyone invest?

I believe viewing non-wealthy individuals as incapable of understanding risk is somewhat condescending. That said, concerns about excessive financialization of life are understandable, especially when striving to reduce class divides so more people can build wealth.

This tension is hard to resolve: In a capitalist society, how do we ensure people can create their own wealth without letting wealth dominate all human relationships?

This could be its own topic. For instance, recent research shows legalized sports betting increases debt and subsequent bankruptcies. In states where it's legal, credit scores dropped by 1%.

Here, one might ask the same question: Should people be free to take on such gambling risks? Yes or no? One study found betting players spent more than usual, though the average deviation was still small.

In reality, most bets come from a small number of high-intensity gamblers. Among depositors ranked by total bets, the top third wagered an average of $299 per quarter—1.7% of their income—while the bottom third averaged just $1.39 per quarter.

This mirrors data from New Jersey:

In New Jersey, 5% of bettors placed nearly 50% of all bets and 70% of all money. Gambling sites profit by extracting losses from these users—just like casinos.

This raises an old question: How do we balance personal freedom when a legal activity significantly impacts a minority?

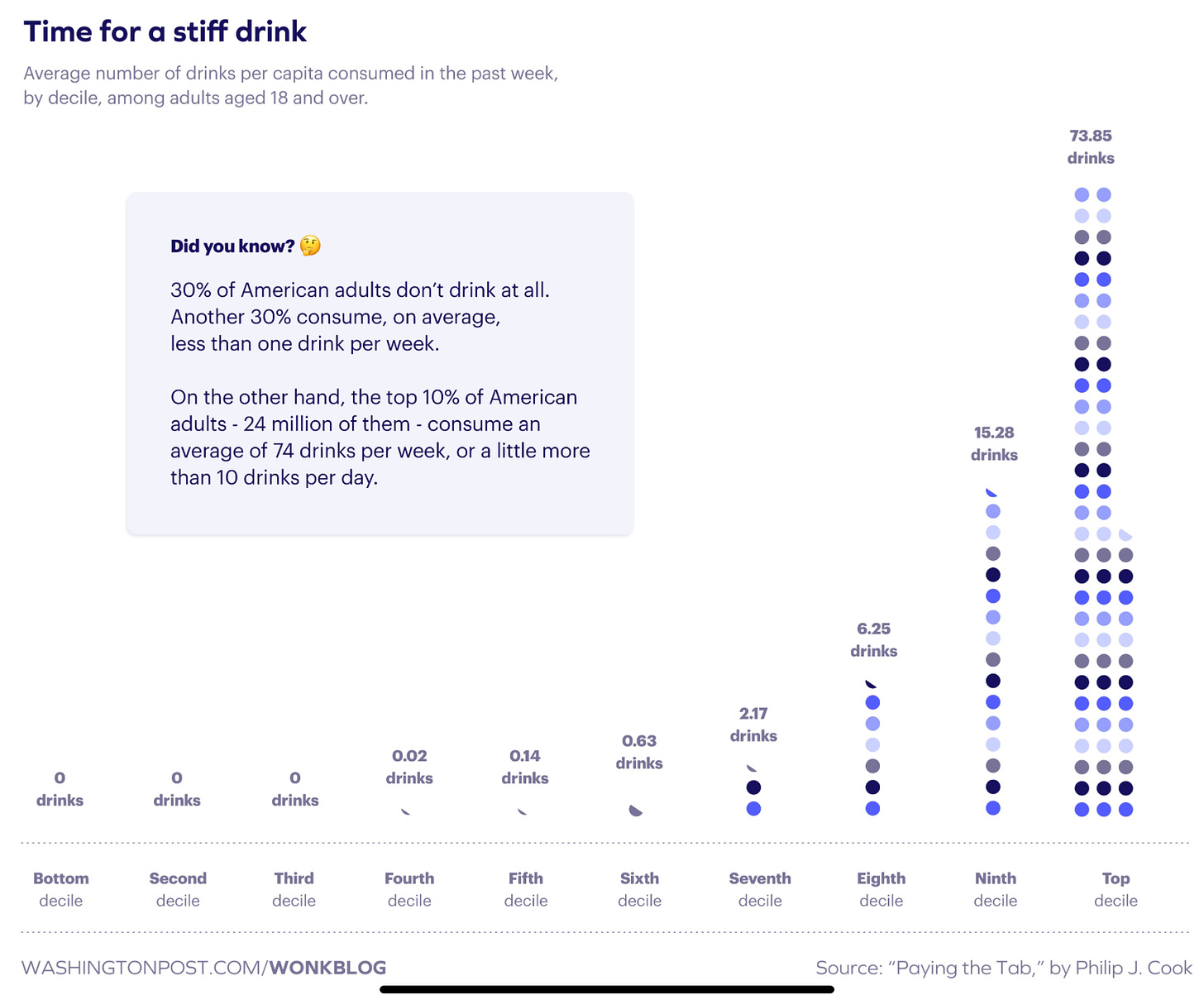

Take alcohol, for example—the situation in many countries is this:

If the top decile of individual freedom leads to systemic harm, society may view it differently. Alcohol is a classic case: despite causing drunk driving, abuse, and intolerable public disorder, it remains socially tolerated. Yet gun control is treated differently—even though most gun owners are responsible, mass and indiscriminate gun violence makes society less forgiving.

Thus, freedoms that seem harmless at the individual level can evolve into complex social problems. Seen this way, financial regulations aren’t just about market order—they’re also about reducing excessive financial transactions in daily life. I understand this, and see why some societies adopt such measures.

Therefore, whether we want to live in a more financialized world is distinct from how we ensure accessibility in today’s world. If you agree we should expand wealth-creation opportunities and accept the trade-offs involved, we can learn from memecoins without fully deregulating.

Capital and liquidity flow into memecoins partly because traditional financial rules were established before the internet and crypto eras. These rules aimed to bring order and investor protection to past times, but in practice, they've worsened inequality. If we update them for 21st-century standards, we might reduce class divides. Then, more people could participate in the process of “producing memes.”

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News