a16z: How Can App Tokens Build Financial Models That Generate Cash Flows?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

a16z: How Can App Tokens Build Financial Models That Generate Cash Flows?

The business model of an application token should be as expressive as the underlying software.

Authors: Mason Hall, Porter Smith, Miles Jennings, Ross Shuel

Compiled by: TechFlow

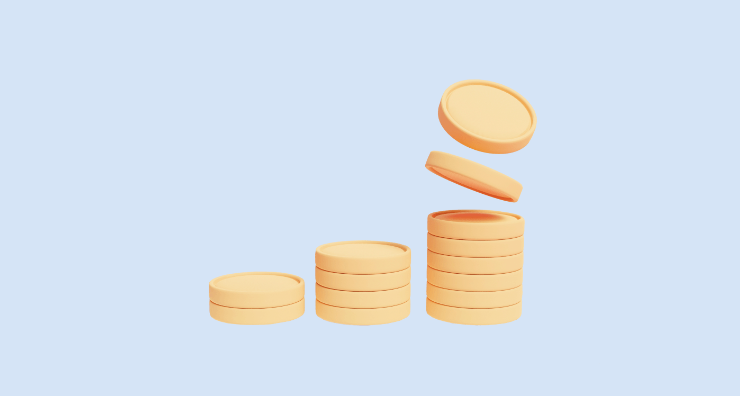

For infrastructure tokens—such as Layer 1 networks (or adjacent parts of the compute stack like Layer 2s)—economic models are relatively mature and well understood, primarily based on supply and demand for blockspace. However, for application tokens—smart contract protocols deploying services on blockchains that convey rights within a "distributed business"—economic models remain under active exploration.

The business model for application tokens should be as expressive as the underlying software itself. To this end, we propose a cash flow model for application tokens—a method enabling applications to create flexible and permissive economic models while allowing users to choose how they are rewarded for the value they provide. This approach generates fees through legally compliant activities, encouraging greater regulatory compliance across jurisdictions. At the same time, it maximizes the value accrued by the protocol and promotes minimal governance.

The principles we share here apply broadly to all Web3 applications—from decentralized finance (DeFi) to decentralized social apps, decentralized physical infrastructure networks (DePIN), and beyond.

Challenges Facing Token Models

Infrastructure tokens are shaped by embedded supply-demand dynamics: as demand increases, supply decreases, and markets adjust accordingly. This economic foundation has been enhanced in many infrastructure tokens, notably through Ethereum Improvement Proposal 1559 (EIP-1559), which implements a base fee burning mechanism for all Ethereum transactions. Yet despite attempts at buy-and-burn models, application tokens lack an equivalent to EIP-1559.

Applications are consumers—not providers—of blockspace, so they cannot rely on collecting gas fees from other users of their blockspace. This is why they must develop their own economic models.

There are also legal challenges: the economic models of infrastructure tokens are relatively insulated from legal risk due to the general-purpose nature of typical blockchain transactions and their use of programmable mechanisms. But for application tokens, the associated applications may depend on facilitating regulated activities and could require mediation by governance token holders—making economic models more complex. Facilitating derivative trading via a decentralized exchange is a highly regulated activity in the U.S., fundamentally different from projects like Ethereum.

This combination of intrinsic and extrinsic challenges means application tokens need different economic models. With this in mind, we propose a potential solution: a way to design protocols that compensates application token holders for services rendered, maximizes protocol revenue, incentivizes compliance, and incorporates minimal governance. Our goal is simple: to give application tokens the same economic foundation enjoyed by many infrastructure tokens—via cash flows.

Our solution focuses on addressing three key problems facing application tokens:

-

Governance-related challenges

-

Value distribution-related challenges

-

Regulated-activity-related challenges

1. Governance-Related Challenges

Application tokens often carry governance rights, and the existence of a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO) can introduce uncertainty not faced by infrastructure tokens. For DAOs with significant operations in the U.S., risks may arise if the DAO controls protocol revenue or intermediates protocol economic activity and renders such activity programmable. To avoid these risks, projects can eliminate DAO control by minimizing governance. For those unable to do so, Wyoming’s new Decentralized Nonprofit Association (DUNA) offers a decentralized legal entity that may help mitigate these risks and comply with applicable tax laws.

2. Value Distribution-Related Challenges

Applications must also be cautious when designing mechanisms that distribute value to token holders. Combining voting rights and economic rights may raise concerns under U.S. securities law, especially for straightforward mechanisms like pro-rata distributions or token buybacks and burns. These resemble dividends and stock buybacks, potentially undermining arguments that tokens should fall under a regulatory framework distinct from equity.

Projects should explore stakeholder capitalism—rewarding token holders in ways that align with contributions to the project. Many projects encourage active participation, including operating frontends (e.g., Liquity), participating in protocols (e.g., Goldfinch), or committing collateral as part of a security module (e.g., Aave). The design space here is vast, but a good starting point is mapping all stakeholders in the project, identifying behaviors worth incentivizing, and determining the overall value the protocol can generate through such incentives.

For simplicity, in this article we assume a basic compensation model that rewards token holders for participating in governance, though alternative schemes exist.

3. Regulated-Activity-Related Challenges

Applications facilitating regulated activities must also proceed carefully when designing value accrual mechanisms for token holders. If these mechanisms accumulate value outside of frontends or APIs that operate in accordance with applicable laws, token holders could profit from illegal activities.

Most proposed solutions to this problem focus on limiting value accrual to activities permitted in the U.S.—for example, only turning on protocol fees for liquidity pools involving specific assets. This constrains projects to the lowest common denominator of regulation and undermines the value proposition of globally autonomous software protocols. It also directly undermines efforts toward governance minimization. Determining which fee strategies are permissible from a regulatory compliance standpoint is not an appropriate task for a DAO.

Ideally, projects should be able to collect fees from any jurisdiction where the activity is permitted, without relying on a DAO to determine what is allowed. The solution is not to require compliance at the protocol level, but to ensure that fees generated by the protocol are only passed through when the frontend or API origin complies with applicable laws and regulations. If the U.S. deems fee collection on certain application-facilitated transactions illegal—even if fully legal elsewhere—it could reduce the token’s economic value to zero. Flexibility in fee accumulation and distribution ultimately means resilience in the face of regulatory pressure.

A Core Issue: Fee Attributability

Fee attributability is critical to mitigating potential risks from non-compliant frontends, while avoiding censorship risks or making the protocol permissioned. With attributability, applications can ensure that any fees accrued by token holders originate only from frontends that are legally compliant in the holder's jurisdiction. Without fee attributability, there is no way to isolate token holders from value accumulated via non-compliant frontends (i.e., fees collected by non-compliant frontends), exposing them to risk.

To make fees attributable, protocols can adopt a two-step application token staking system design:

-

Step One: Identify the frontend sourcing the fee

-

Step Two: Route fees to different pools based on custom logic

Mapping Frontends

Fee attributability requires mapping domains to public/private key pairs. Without this mapping, malicious frontends could forge transactions, pretending they were submitted from a legitimate domain. Cryptography allows us to “register” frontends, permanently recording the mapping between a domain and a public key, proving that the domain controls the key, and using the private key to sign transactions. This enables us to attribute transactions—and thus fees—to specific domains.

Routing Fees

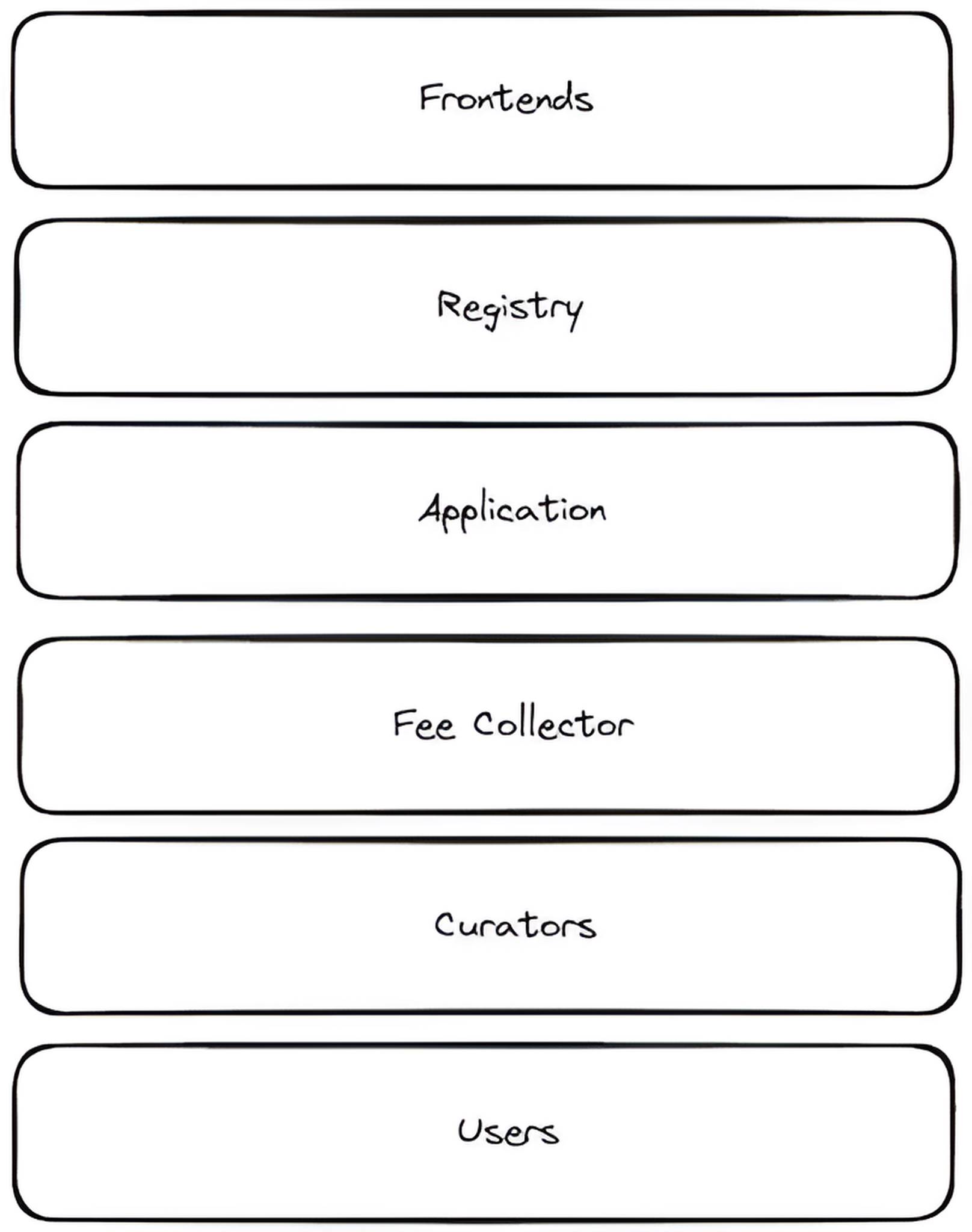

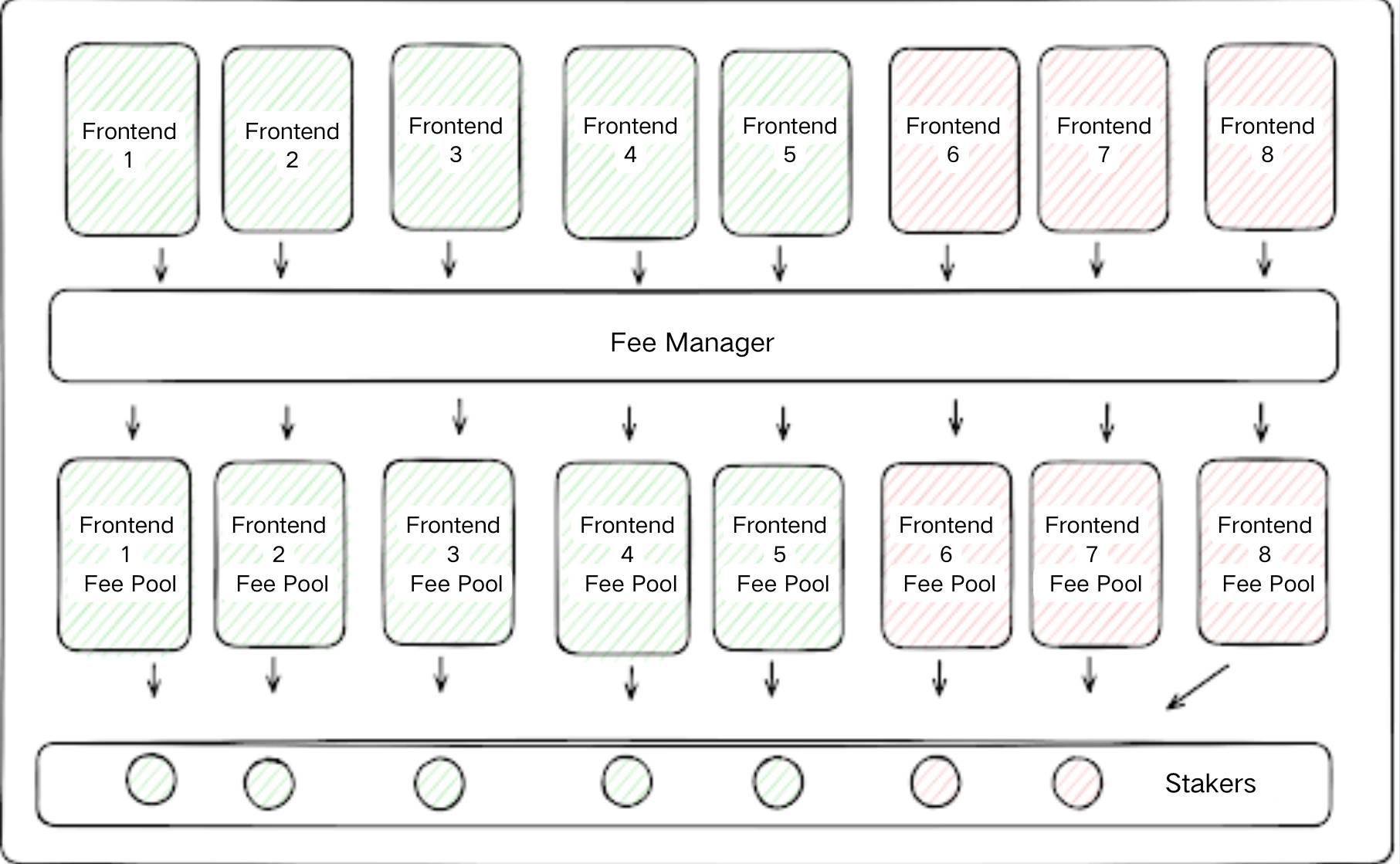

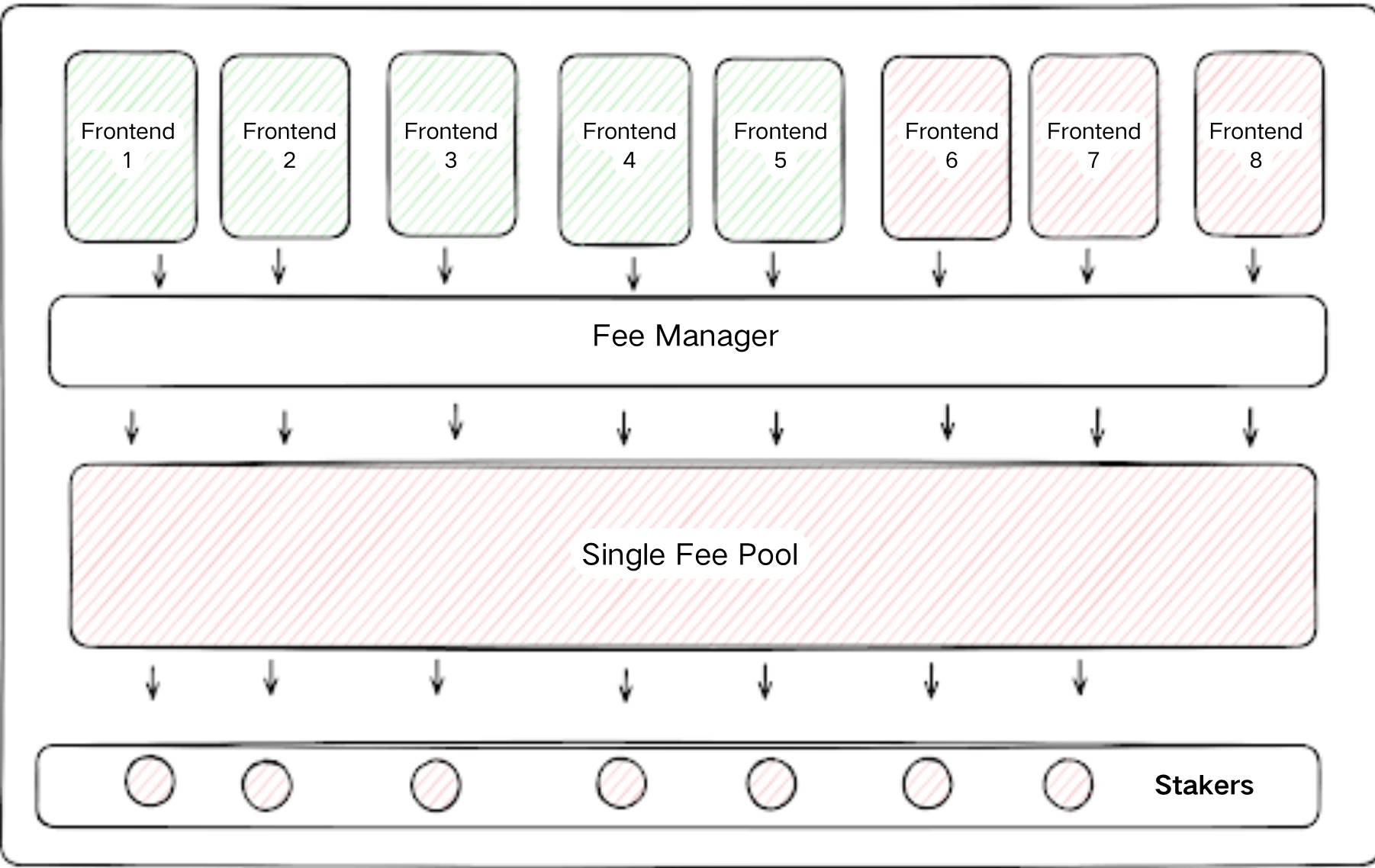

Once fee sources are attributable, the protocol can decide how to allocate those fees—protecting token holders from fees derived from illegal transactions, without increasing the decentralized governance burden on the application DAO. To illustrate, consider the design spectrum for application token staking—from one staking pool per frontend to one single pool for all frontends.

In the simplest construct, fees from each frontend could route to a separate, frontend-specific staking module. By choosing which frontends to stake into, token holders could decide which fees they receive and avoid any that might expose them to legal risk. For instance, a token holder could stake only into modules linked to frontends that have obtained all necessary regulatory approvals in Europe. While this design sounds simple, it is practically quite complex. There could be 50 staking pools for 50 different frontends, and fee dilution could negatively impact token value.

At the other end of the design spectrum, fees from every frontend could be pooled together—but this defeats the purpose of fee attributability. If all fees are pooled, there’s no way to distinguish between compliant and non-compliant frontends; one bad actor could spoil the entire batch. Token holders would be forced to choose between receiving no fees at all or staking into a pool where they’d benefit from illegal activities conducted by non-compliant frontends in their jurisdiction—a choice that may deter many from participating, or push the system back toward current suboptimal designs where the DAO must assess where fees can be applied.

Solving Fee Attributability Through Curation

These complexities can be resolved through curation. Imagine a permissionless smart contract application protocol with fees and a token. Anyone can create a frontend for the application, and each frontend can have its own staking module. Let’s call one such frontend for the protocol App.xyz.

App.xyz can follow specific compliance rules in its jurisdiction. Application activity from App.xyz generates protocol fees. App.xyz has its own staking module. Token holders can either stake directly into that module or stake with curators who selectively pick a basket of frontends they believe are compliant. These stakers earn returns in the form of fees generated by the frontends they’ve staked into. If a frontend generates $100 in fees, and 100 entities each stake 1 token, each entity is entitled to $1. Curators may initially charge a fee for their service. In the future, governments could issue on-chain certifications of frontend compliance within their jurisdictions, helping protect consumers while enabling automated curation benefits.

A potential risk in this model is that non-compliant frontends may have lower operating costs due to the absence of compliance overhead. They might also design models that rebate frontend fees to traders, further incentivizing circumvention. Two factors can mitigate this risk. First, most users actually prefer compliant frontends that follow local laws—especially large, regulated institutions. Second, governance can play a role as a last resort or “veto power,” disincentivizing bad actors by targeting non-compliant frontends that repeatedly violate rules and threaten the application’s viability.

Finally, all fees from transactions not initiated through registered frontends will go into a single omnibus staking module, enabling the protocol to capture revenue generated by bots and others interacting directly with the protocol’s smart contracts.

From Theory to Implementation: Putting the Method into Practice

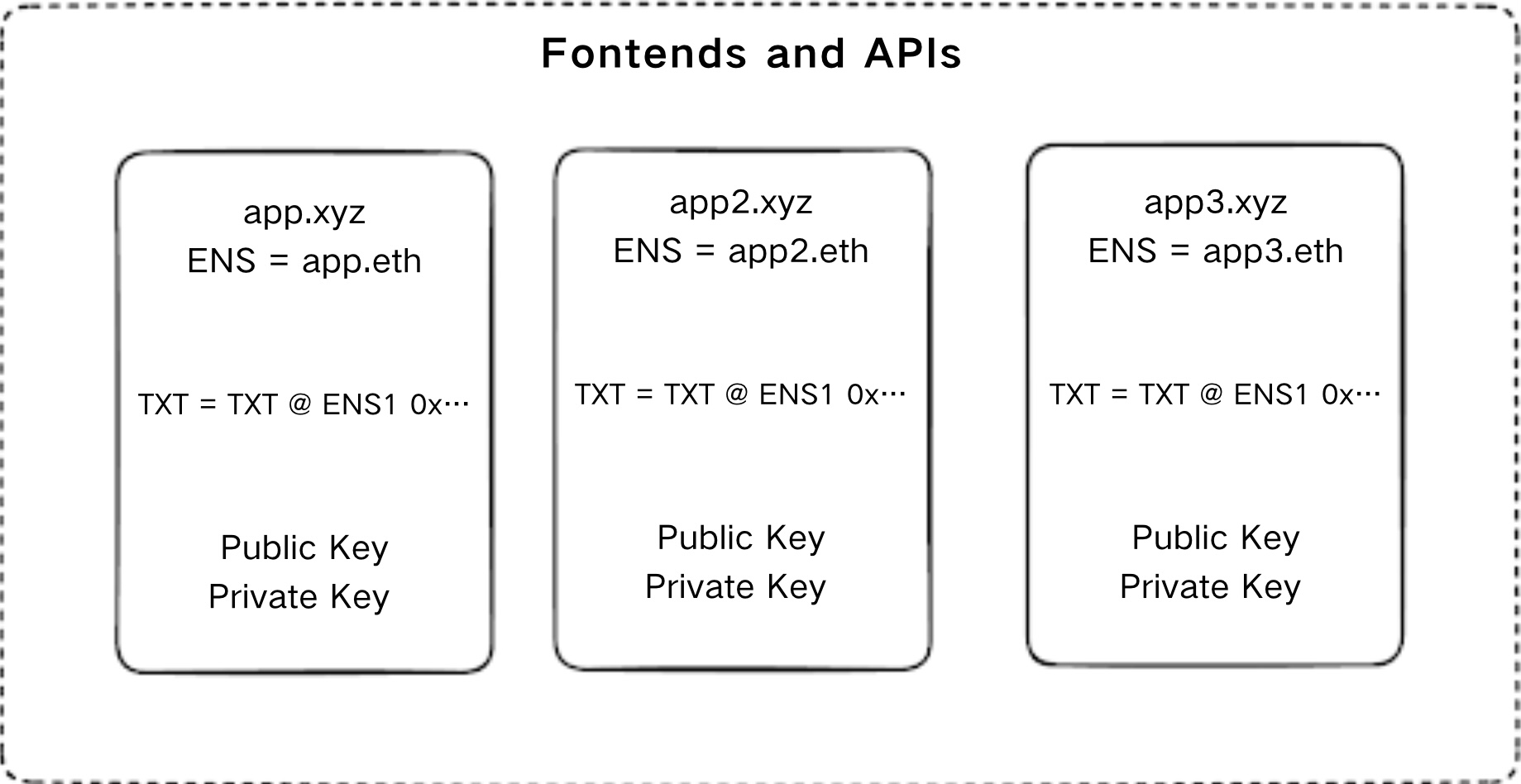

Let’s walk through the application token stack in more detail. To enable frontend staking, the protocol needs to establish a registration smart contract that frontends must register with.

-

Each frontend or API can add a special TXT record in the DNS records of its domain, similar to ENS DNS integration. This TXT record contains the public key from a key pair generated by the frontend, known as a certificate.

-

The frontend client can call the register() function and prove ownership of its domain. The mapping between the domain and the certificate’s public key, along with reverse mapping, will be stored.

-

When creating a transaction via the client, it also signs the transaction payload with its certificate’s public key. These are bundled and passed to the application’s smart contract.

-

The application’s smart contract verifies the certificate, checks that it corresponds to the correct transaction subject, and confirms registration. If valid, the transaction is processed. Fees generated by the transaction are then sent along with the domain name (from the registry) to the FeeCollector contract.

-

The FeeCollector allows curators, users, validators, and others to stake tokens directly into a specific domain or a group of domains. These contracts must track the number of staked tokens per domain, each address’s share in that stake, and their staking duration. Popular liquidity mining implementations can serve as a starting point for this contract logic. Users staked to curators (or directly to the fee management contract) can withdraw their proportional share of fees based on the quantity of application tokens staked to that domain. The architecture can resemble MetaMorpho/Morpho Blue.

This scheme can be introduced without increasing the governance burden on the application DAO. In fact, governance responsibilities may decrease, as fee switches can be permanently turned on for all transactions facilitated by the protocol, eliminating any DAO control over the protocol’s economic model.

Additional Considerations by Application Type

While these principles broadly apply to application token economic models, additional fee considerations may arise depending on the application type—for example, apps built on Layer 1 or Layer 2, app chains, and apps built using rollups.

Considerations for L1/L2 Applications

Applications on Layer 1 or Layer 2 blockchains deploy smart contracts directly on-chain. When users interact with the application’s smart contract, fees are charged. Typically, this interaction occurs via a user-friendly frontend (such as an app or website) that serves as an interface between retail users and the underlying smart contract. In this case, any fees will originate from that frontend. The earlier example with app.xyz illustrates how the fee system works in a Layer 1 application.

Applications can also adopt whitelist or blacklist approaches to filter frontend fees instead of relying on curators. The goal here is to ensure that neither token holders nor the protocol as a whole profits from or benefits via illegal activities, adhering to laws and regulations in specific jurisdictions.

In the whitelist approach, the application publishes a set of frontend rules, creates a registry of frontends following these rules, issues certificates to opt-in frontends, and requires frontends to stake tokens to receive a portion of application fees. If a frontend violates the rules, it becomes ineligible for fee distribution and its certificate is revoked.

In the blacklist approach, the application does not create any rules upfront, but launching a frontend for the application is not permissionless. Instead, the application requires any frontend to provide a legal opinion from a law firm confirming compliance with regulations in its jurisdiction. Once received, the application issues a certificate authorizing fee distribution, which is only revoked if the application receives notice from regulators that the frontend is non-compliant.

The fee pipeline will resemble the example provided earlier.

Both approaches significantly increase the decentralized governance burden, requiring the DAO either to establish and maintain a rule set or evaluate legal opinions on compliance. In some cases, this may be acceptable, but in most, outsourcing compliance burden to curators will be preferable.

Considerations for App Chains

App chains are blockchains dedicated to a specific application, where validators work exclusively for that application.

In return for their work, these validators are compensated. Unlike Layer 1 blockchains, where validators are typically rewarded via inflationary token issuance, some app chains (like dYdX) pass customer fees directly to validators.

In this model, token holders must stake to validators to earn rewards. Validators become curated staking modules.

This workset differs from Layer 1 validators. App chain validators process specific transactions from a particular application. Due to this distinction, app chain validators may face greater legal risk due to the nature of the activities they facilitate. Therefore, the protocol should allow validators the freedom to conduct their work according to local laws and personal comfort levels. Importantly, this can be achieved without jeopardizing the app chain’s permissionlessness or exposing it to significant censorship risk—as long as the geographic distribution of validators remains decentralized.

An app chain architecture wishing to leverage the benefits of fee attributability will resemble that of a Layer 1 application up to the fee pipeline. But validators will be able to use frontend mappings to determine which frontends they wish to serve. Fees from any given transaction will be distributed among the active validator set, while inactive validators opting out will miss these fees. From a fee perspective, validators function identically to the curated staking modules discussed above, and those staking to them can ensure they do not earn income from any illegal activities. Validators may also appoint curators to determine which frontends are compliant within their respective jurisdictions.

Considerations for Application Rollups

Rollups have their own blockspace but inherit security from another chain. Most rollups today rely on a single sequencer to order and include transactions, although transactions can be submitted directly to Layer 1 via a process called “forced inclusion.”

If these rollups are application-specific and treat their sequencer as the sole validator, fees generated from transactions included by the sequencer can be distributed to stakers based on a curated set of compliant frontends or as a general pool.

If the rollup decentralizes its sequencer set, sequencers become de facto curated staking modules, and the fee pipeline resembles that of an app chain. Sequencers replace validators in fee distribution, with each sequencer deciding which frontends’ fees to accept.

While many possible models exist for application tokens, offering curated staking pools represents a promising path forward—one that helps address the unique external challenges faced by applications. By recognizing both the internal and external challenges applications face, founders can better design application token models from the ground up for their projects.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News