The Path to General Computation on Bitcoin: Envisioning STARKs for Bitcoin Scaling

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Path to General Computation on Bitcoin: Envisioning STARKs for Bitcoin Scaling

This article will discuss the task of implementing general-purpose computing on Bitcoin and the various steps involved.

Author: StarkWare

Translation: Starknet Chinese Community

1. Introduction

In this article, we will discuss the task of achieving general-purpose computation on Bitcoin and the various steps involved. Indeed, enabling arbitrary logic computation on Bitcoin scripts is an attractive goal, as it brings Bitcoin into the realm of non-custodial applications and decentralized finance.

Previously, due to two major limitations—the script length limit and the expressiveness of opcodes—general computation on Bitcoin was almost considered impossible. The former prohibits any transaction beyond short scripts, while the latter limits what computations script opcodes can perform. Together, these restrictions created a harsh landscape for computational feasibility on Bitcoin, as many applications could not be realized under such constraints.

However, in recent years, this situation has improved significantly. In fact, with the Taproot upgrade in 2021, the script length restriction was lifted, allowing Bitcoin scripts to become substantially longer (in fact, Taproot scripts even allow paying only to part of the script on-chain, though we won't explore this feature here). Additionally, to address the limitation in opcode expressiveness, we have found that a single simple opcode is sufficient to effectively achieve unlimited expressiveness.

The aforementioned opcode is called OP_CAT, which has been disabled in Bitcoin script since 2012. It is a very simple opcode that allows concatenating elements on the stack, and can be non-invasively activated on Bitcoin via a soft fork using just 13 lines of code, as detailed in BIP-0347. Deriving such immense power from an apparently insignificant opcode is no small feat, and thus the central objective of this article is to elaborate precisely on this point.

Below, we will delve into computation on Bitcoin, starting with how it is implemented and its existing limitations.

Next, we will outline two tools—Covenants and STARK proofs—and demonstrate that if both can run within Bitcoin scripts, they enable general computation on Bitcoin. Furthermore, we will argue in this article that thanks to STARK proofs, such computation can also gain several useful properties:

-

Scalability—On-chain transaction processing and computation become feasible at extremely low fees.

-

Expressiveness—Logic can be programmed in different languages more powerful than Bitcoin script. This is crucial for usability and security in Bitcoin programming.

-

On-chain Security—Regardless of the computation, Bitcoin script only verifies mathematical proofs of delegated computation.

-

Flexibility—Computation on Bitcoin can store global state, enabling a wide range of applications.

Finally, we will discuss OP_CAT and how it enables the above tools. We will also mention some of our efforts in this area and discuss future directions.

Note: This article simplifies certain technical aspects to provide a clear mental model. When implementing the ideas presented here, "the devil is in the details."

2. UTXO Model and Locking Scripts

This section provides a brief overview of Bitcoin's UTXO model, where each UTXO is locked behind a locking script. If you are already familiar with this, feel free to skip to the next section.

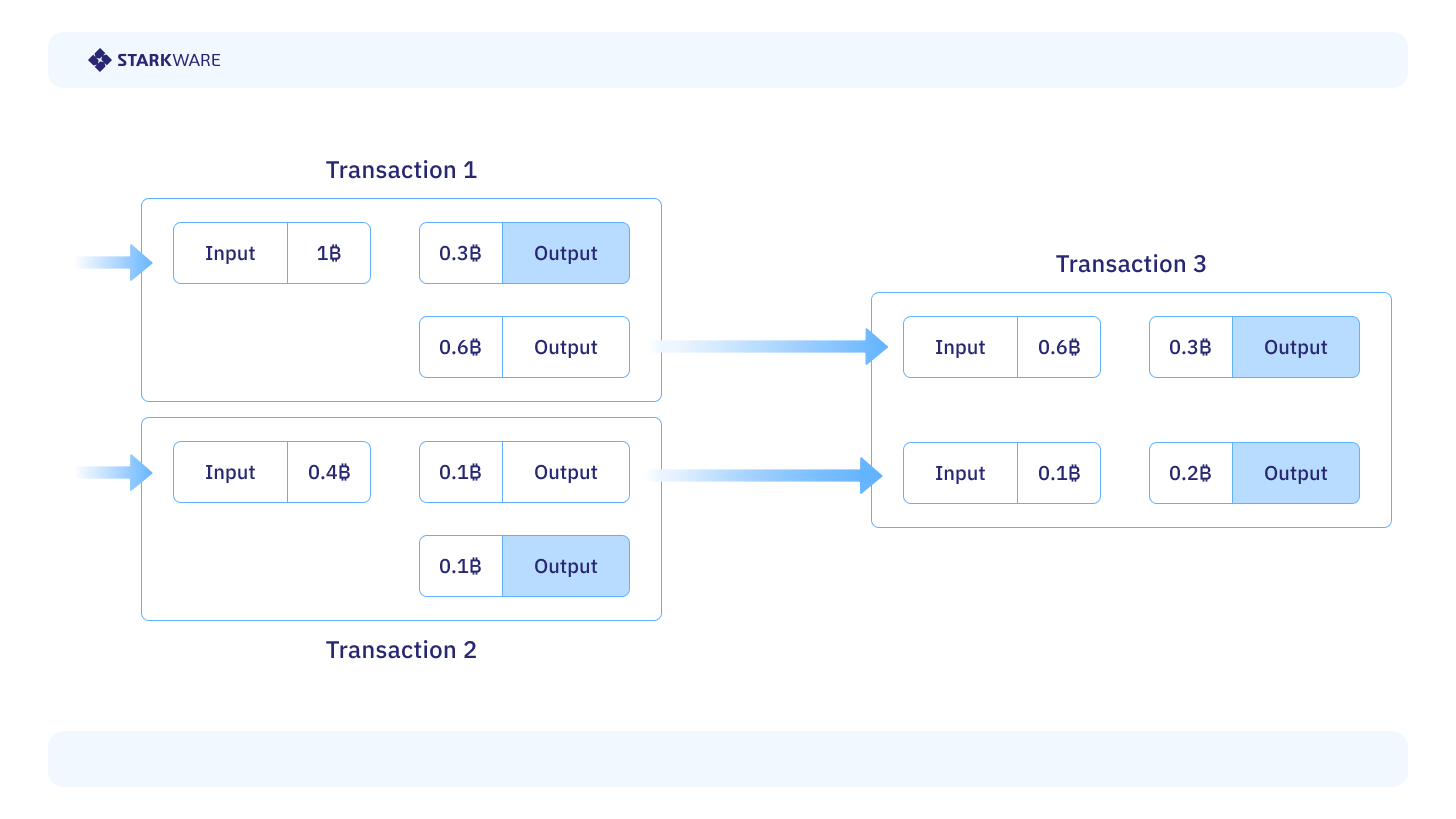

The first step in understanding Bitcoin transactions is recognizing that they are structured and processed according to the Unspent Transaction Output (UTXO) model, as shown in Figure 1. Bitcoin transactions can have multiple inputs and outputs, with each output representing a certain amount of bitcoin that can be spent by another transaction. Correspondingly, a transaction’s inputs represent spending from previous Bitcoin transaction outputs. Naturally, the total amount of bitcoin in the inputs must approximately equal that in the outputs (with the difference being the fee paid to miners).

Figure 1: Transactions in the UTXO model. Each transaction input and output is associated with a certain amount of bitcoin, where the total amount in outputs cannot exceed that in inputs. Unspent Transaction Outputs (UTXOs) are shown in blue.

Each transaction output is locked by a locking script (scriptPubKey), which either accepts or rejects a given input (scriptSig) provided by the so-called spender. Therefore, to transfer funds from an Unspent Transaction Output (UTXO), you must generate the correct scriptSig and include that UTXO as an input in your transaction.

By default, the locking script simply verifies a digital signature against a hardcoded public key, defining the ownership of the locked bitcoins. More generally, whenever a UTXO exists, the person who can provide the correct scriptSig is considered the owner of the bitcoins locked behind the corresponding locking script. Thus, each Bitcoin owner’s total balance is determined cumulatively by all UTXOs associated with that owner (e.g., all UTXOs digitally signed by the same individual).

3. Limitations of Bitcoin Script

The previous section outlined the general case of locking scripts and their interaction with Bitcoin transactions and Bitcoin itself. This section focuses on the locking scripts themselves and their composition.

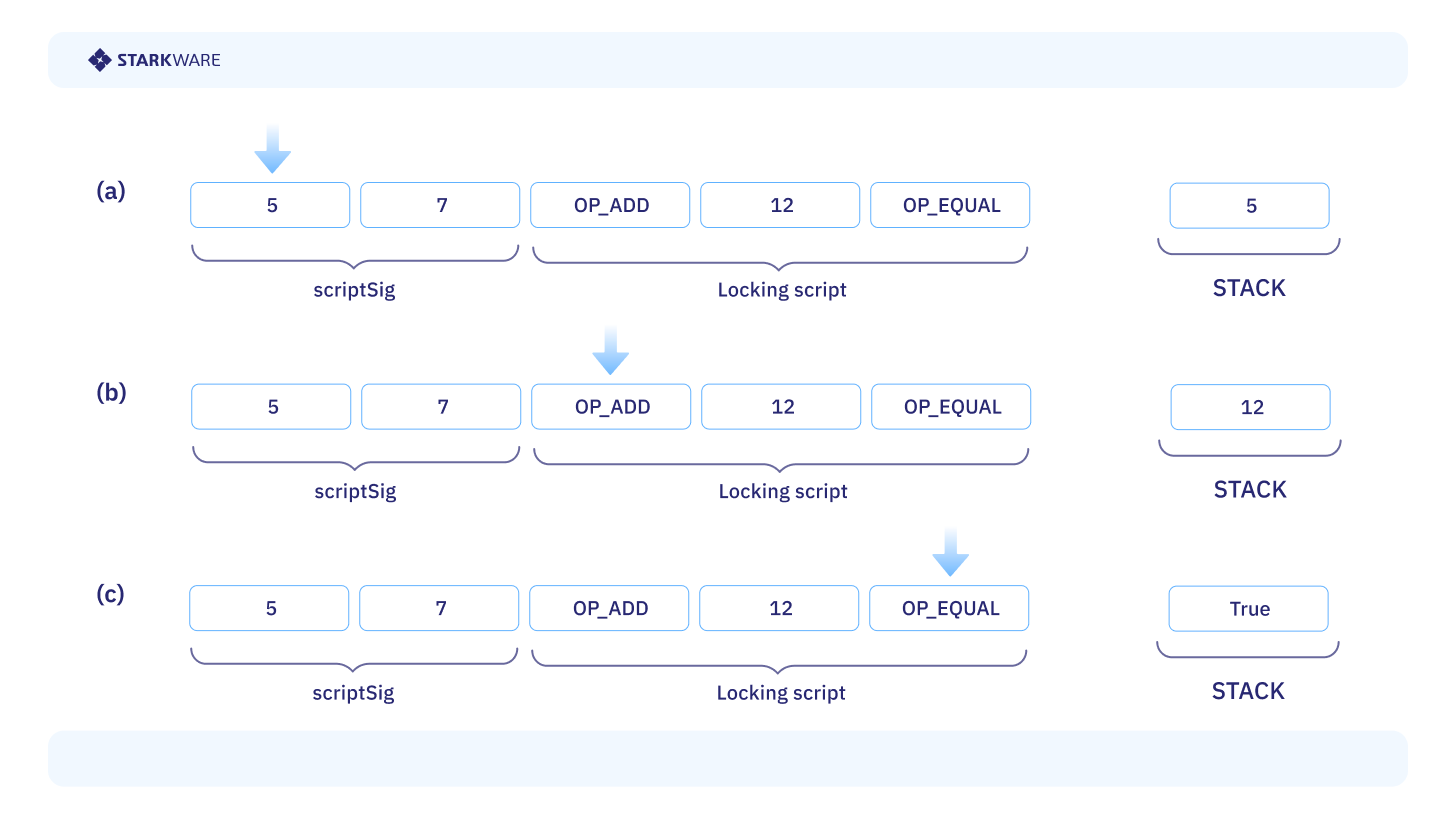

Locking scripts on Bitcoin are written in a stack-based language similar to Forth, known as "Bitcoin script." Since Bitcoin script lacks loops, we measure script cost by the number of required opcodes, as script length is proportional to execution time. In Figure 2, we see a schematic of a simple program checking whether the sum of two inputs equals 12.

Figure 2*: A simple program checking whether the sum of two input values equals 12. Execution proceeds by concatenating the scriptSig with the locking script and processing opcodes left to right. The scriptSig only pushes elements onto the stack. (a) First step of computation. (b) Mid-computation. (c) Final step (locking script accepts input).

We must emphasize that Bitcoin script has many limitations, making even simple logic development difficult or outright impossible. These limitations include:

-

Stack size limited to a maximum of 1000 elements.

-

No multiplication opcode (in fact, even 31-byte integer multiplication requires simulating around 14,000 opcodes).

-

For Pay2Taproot output types (post-Taproot upgrade), a single transaction can hold up to approximately 4 million opcodes—filling an entire block—while other output types are limited to only 10,000 opcodes.

-

Arithmetic operations (addition, subtraction) are limited to 4-byte elements.

The 4-byte limit mentioned last is particularly problematic. In practice, this means you cannot modify long elements, such as 20-byte or longer elements required for cryptographic operations.

For example, common operations like concatenating data and applying cryptographic functions are impossible unless you ignore native crypto opcodes and simulate them as operations on arrays of 4-byte elements. The latter is extremely costly, as a single hash operation might require hundreds of thousands of opcodes to simulate.

Lastly, we note that due to the difficulty of developing Bitcoin scripts, code is naturally more prone to errors and vulnerabilities.

4. Challenges in Maintaining State Within Bitcoin Scripts

While the previous section already demonstrates significant shortcomings of Bitcoin script, we believe the biggest limitation of Bitcoin locking scripts is that they can only read the spender’s input. This implies two serious limitations:

-

Bitcoin scripts lack statefulness. That is, they cannot read/write storage unit data. By analogy to the Ethereum Virtual Machine, there are no equivalents to SLOAD/SSTORE opcodes, which are fundamental for general computation.

-

Bitcoin scripts cannot enforce how bitcoins are spent (except in rare cases). This can be addressed using Covenants, which grant locking scripts this capability. (Imagine a simple application like an on-chain vault that operates by restricting allowed spending addresses. More broadly, Covenants are an extremely powerful tool with wide-ranging applications.)

Then, we will see that by building Covenants, we can already achieve statefulness. Intuitively, this is because you can use Covenants to simulate reading and writing stored data within the transaction data itself.

Indeed, the above does not fully capture the entirety of Bitcoin script and its complexities. But at the very least, we can affirm that writing Bitcoin scripts is far from easy. Bitcoin scripts have very strict limitations:

-

Stack size cannot exceed 1000 elements.

-

Simple operations like multiplication must be simulated using many opcodes. Generally, you must write logic using the cumbersome Bitcoin script language.

-

Operations must be performed on elements encoded in 4-byte form. In particular, you cannot operate on or alter inputs to cryptographic opcodes.

-

Your logic cannot maintain state and must fit within a single transaction.

-

Once authenticated, your logic cannot control how bitcoins are spent.

Moreover, coding under these constraints is prone to bugs and vulnerabilities.

While very simple applications like payments can meet the above constraints, any slightly complex application hits roadblocks. Below, we will learn how Covenants and STARK proofs can help us overcome these limitations. Additionally, we will discuss how OP_CAT helps Bitcoin script achieve the above functionalities.

5. Achieving Smart Contracts on Bitcoin via Covenants

This section explains how Covenants in Bitcoin maintain logical state and more generally describes what “smart contracts” on Bitcoin look like. Here, smart contracts refer to stateful logic containing a set of functions that can be invoked according to predefined rules, transitioning state between different valid states.

More specifically, Bitcoin contracts require the following capabilities:

-

Persistent logic and state

-

Ability to control logic/state transitions

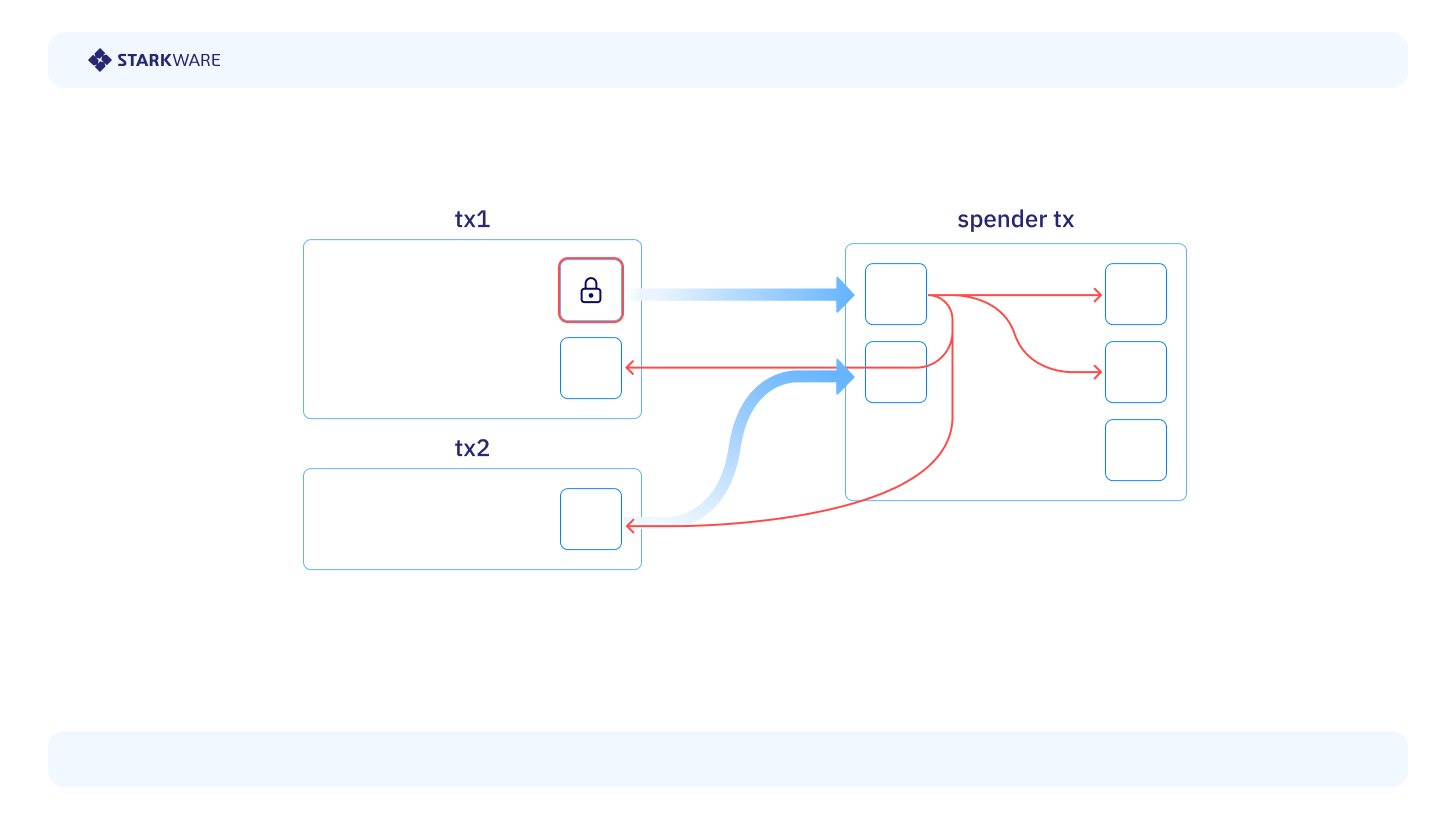

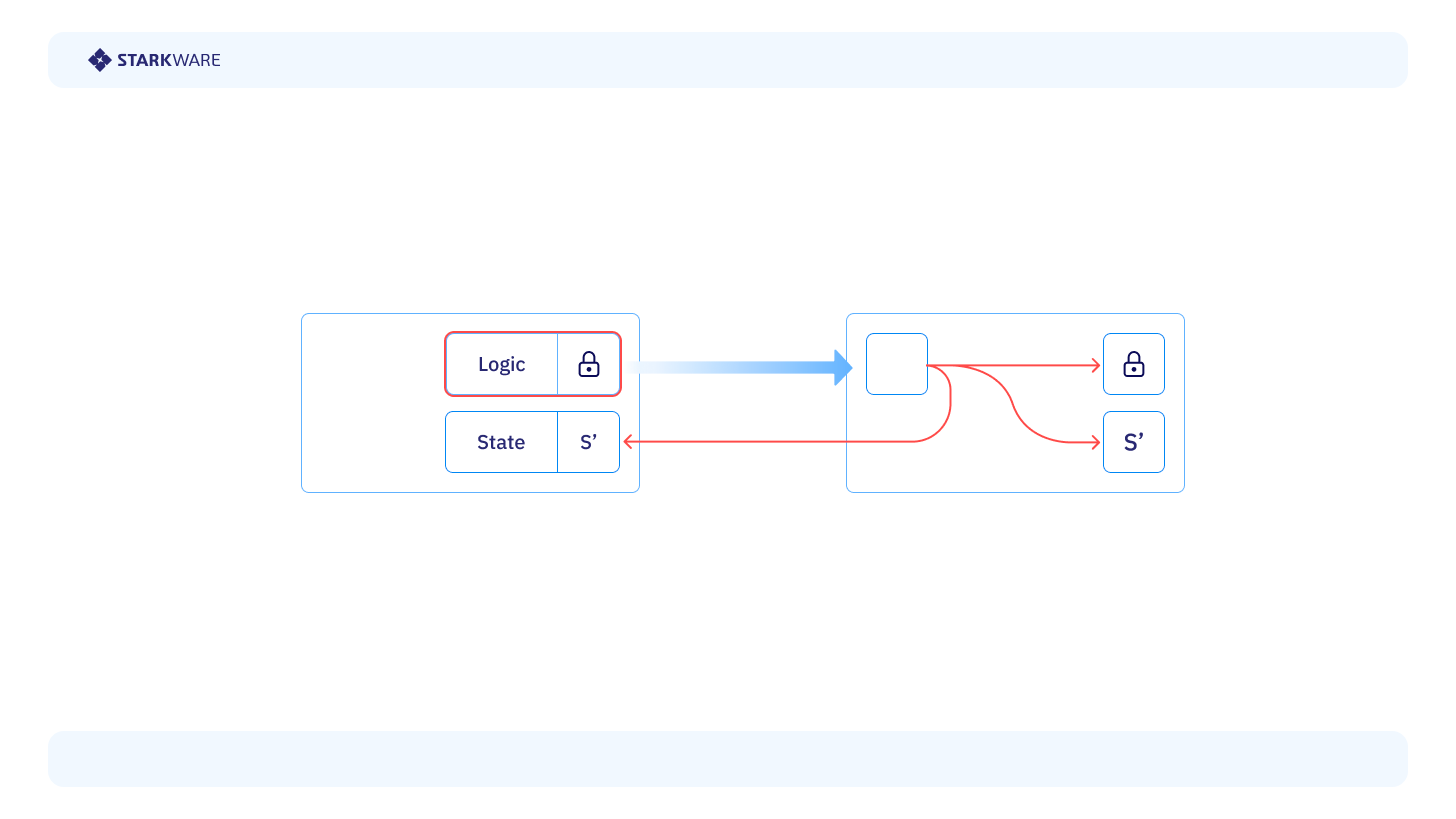

As previously mentioned, these capabilities can be achieved through Covenants. Recall that by default, locking scripts can only read directly provided input data (scriptSig). However, with Covenants, locking scripts can read all data fields of the spender’s transaction, data fields of the transaction containing the locking script, and even data from other transactions. Figure 3 illustrates various parts accessible to a locking script when using Covenants.

Figure 3: Data fields (indicated by red arrows) accessible to a locking script (visualized as a lock). Besides accessing data fields of the spender’s transaction, the locking script can also access data fields of the transaction containing itself (tx1), and those of another transaction (tx2) simultaneously spent by the spender’s transaction.

We contend that the Covenants described above are sufficient to build general smart contracts on Bitcoin. In fact, the general approach involves encoding state directly within transaction data and verifying its validity when transitioning to new values. To do so, our transaction will have two outputs:

-

The first output holds the contract logic (via the locking script) and the funds locked in the contract.

-

The second output holds the smart contract’s current state. This UTXO’s locking script stores only state and is never spent (it effectively locks zero bitcoins).

The locking script logic will enforce the following rules:

-

The spender’s transaction must have exactly the same structure (only two outputs, with all funds locked in the first output);

-

The first output must have the identical locking script logic;

-

The second output must represent a valid state;

-

The inputs provided to the current locking script must convince it that the transition from current to new state is valid (validity defined by the logic designer)

Figure 4 illustrates this structure. As Weikeng Chen wrote, many have suggested formal names for this structure, and “state caboose” has emerged as a leading candidate. A caboose is a railroad car attached to the end of a freight train, serving as a dedicated space for crew members and their work.

Figure 4: A smart contract on Bitcoin enabled by Covenants, following the “state caboose” design pattern. The locking script ensures the spender’s transaction has the same structure and locking script, and contains a valid new state S’, with a valid transition from previous state S.

As a simple example, consider a basic counter smart contract. Its state increments by a value provided by the spender, effectively invoking an “accumulate” function. This counter smart contract is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5: A simple smart contract accumulating inputs (scriptSig) into its state via addition.

Finally, it should be noted that to “call the contract” and transition it to a new valid state, users must create a new spending transaction for each call. Unlike Ethereum smart contracts, Bitcoin smart contracts are inherently sequential, requiring transactions to commit to both current and new states. This sequential nature must be considered when building smart contracts on Bitcoin. While some schemes may alleviate this constraint, we will not discuss them here.

Overall, we have seen that Covenants enable smart contracts on Bitcoin, and theoretically, arbitrarily long computations can be performed on Bitcoin when divided across sufficiently many transactions. However, using only Covenants still faces most limitations of Bitcoin script—stack size caps, limited opcode counts, and the general need to program under Bitcoin script’s constraints.

Below, we will explore how the STARK proof system alleviates these limitations by minimizing blockchain footprint of computation on Bitcoin and enabling scripting in entirely different languages. This approach significantly improves programming efficiency and safety.

6. Bitcoin STARK Verifier

The purpose of this section is to explore how computation can occur on Bitcoin while minimizing actual computation performed within Bitcoin scripts. Our general method is computation delegation: moving computation off-chain (possibly involving multiple parties), with only the verification step occurring on-chain within Bitcoin scripts.

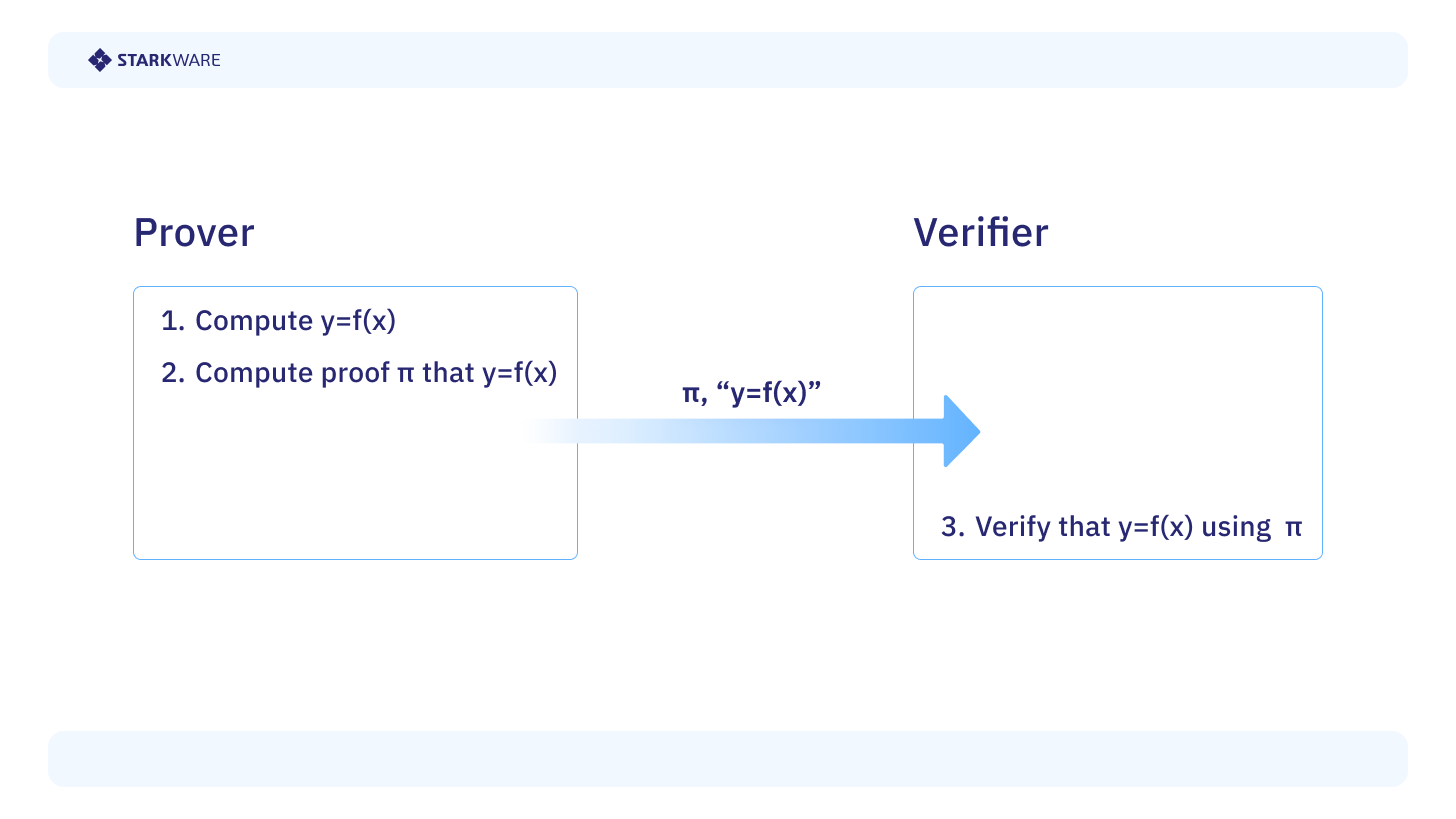

This raises the question: How can we ensure off-chain computation is correctly executed? A natural candidate solution is a proof system. Simply put, a proof system allows Alice (prover) to convince Bob (verifier) of the truth of a statement by providing a “proof,” with the key features that:

-

The verifier performs less work compared to verifying without the prover’s assistance.

-

Additionally, the verifier is protected from being deceived by the prover into believing a false statement.

The proven statement can be nearly anything—from solutions to puzzles to, more relevantly, examples of delegated computation. Specifically, Alice proves f(x)=y to Bob, without requiring Bob to compute f(x) himself, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Proof system for computation delegation. The prover computes y=f(x) and convinces the verifier of its correctness. Crucially, if y≠f(x), the prover cannot convince the verifier otherwise.

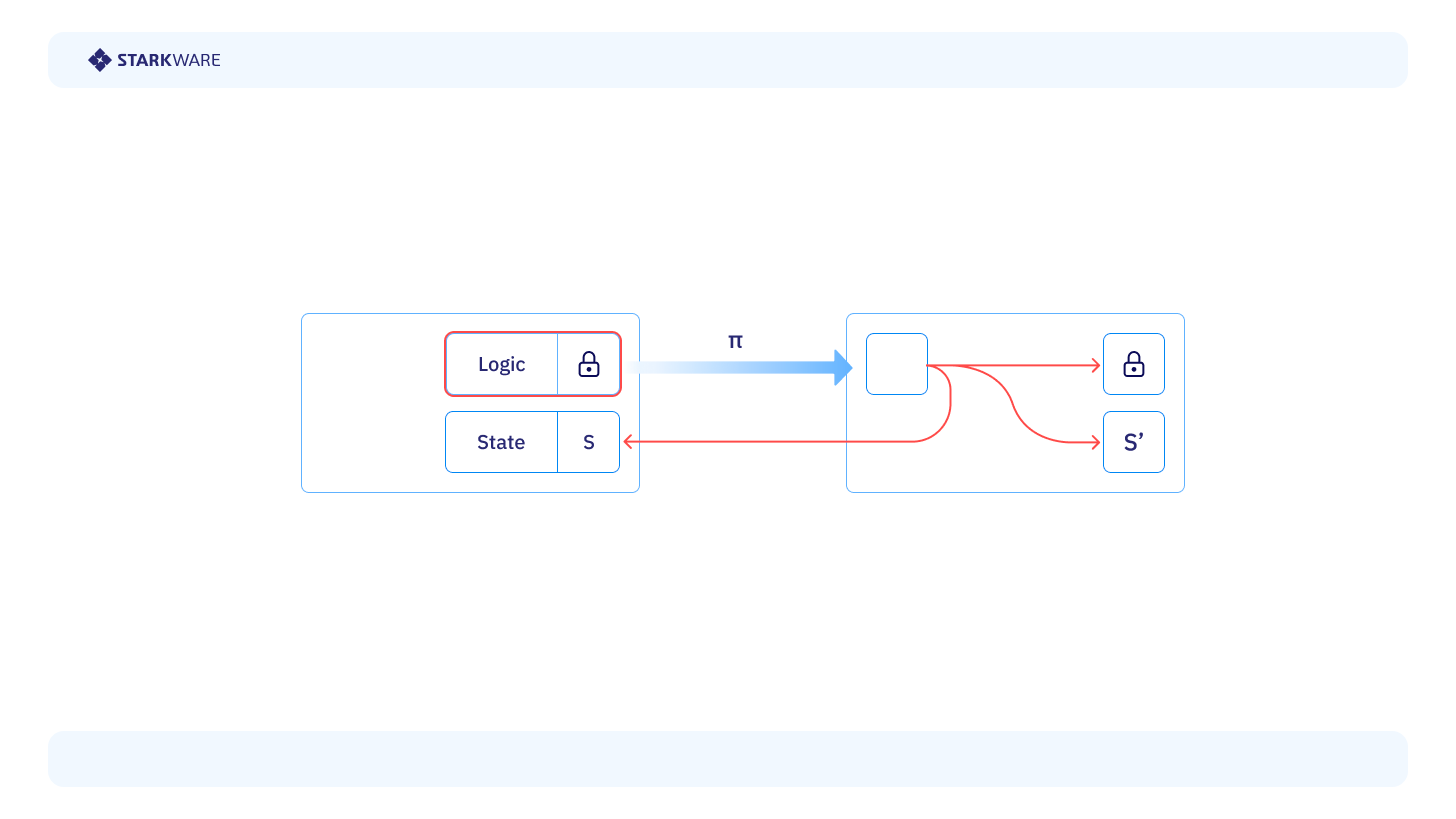

Thus, our method to reduce computational footprint on blockchain is to implement a proof system verifier within Bitcoin script. Therefore, to invoke a smart contract, the caller provides a proof of correct state transition, and the Bitcoin smart contract verifies the correctness of this proof instead of directly checking the state transition (see Figure 7).

Moreover, this approach offers a crucial benefit: Bitcoin script logic can remain fixed and independent of the application, greatly reducing error risks and simplifying audits. This stems from the simple fact that the same verification algorithm can verify statements like y=f(x) or y=g(x) without prior knowledge of the function to be computed.

Figure 7: A smart contract on Bitcoin via Covenants, following the “state caboose” design pattern in Figure 4, but now including a verifier. This time, the locking script no longer checks directly whether the transition from S to S’ is valid, but instead verifies a proof of that transition’s correctness.

Although many proof systems exist, we choose STARK (Scalable Transparent ARgument of Knowledge) due to its appealing characteristics:

-

Post-quantum secure

-

No trusted setup required

-

Does not introduce new cryptographic assumptions to Bitcoin

-

Fastest scaling

-

Battle-tested and trusted in settlements exceeding one trillion dollars

Finally, compared to other proof systems⬇️

STARK is Bitcoin-friendly—that is, its verifier component is easier to implement in Bitcoin script. Fundamentally, this is because STARK relies primarily on hashing, involving minimal algebraic operations compared to pairing-based proofs.

Algebraic operations are expensive in Bitcoin script, explaining why STARK is well-suited for Bitcoin. Moreover, the Circle-STARK variant, due to its small field size, is especially Bitcoin-friendly.

Therefore, since Bitcoin verifiers can relatively easily validate any computation, we can choose which type of computation to verify. Notably, this could even be some form of CPU execution. Furthermore, we can design high-level programming languages atop CPUs. For this, we at StarkWare developed Cairo, a Rust-like, human-friendly, and secure programming language specifically designed for efficient proving and verification. Proving Cairo execution on Bitcoin offers significant advantages.

Overall, by combining STARK verifiers with Covenants, we can achieve general computation on Bitcoin. Moreover, this computation gains the following attractive additional properties:

-

Scalability—On-chain transaction processing and computation become feasible at extremely low fees.

-

Expressiveness—Logic can be programmed in different languages more powerful than Bitcoin script. This is crucial for usability and security in Bitcoin programming.

-

On-chain Security—Regardless of the computation, Bitcoin script only verifies mathematical proofs of delegated computation.

-

Flexibility—Computation on Bitcoin can store global state, enabling a wide range of applications.

7. Concatenation and Beyond Using OP_CAT

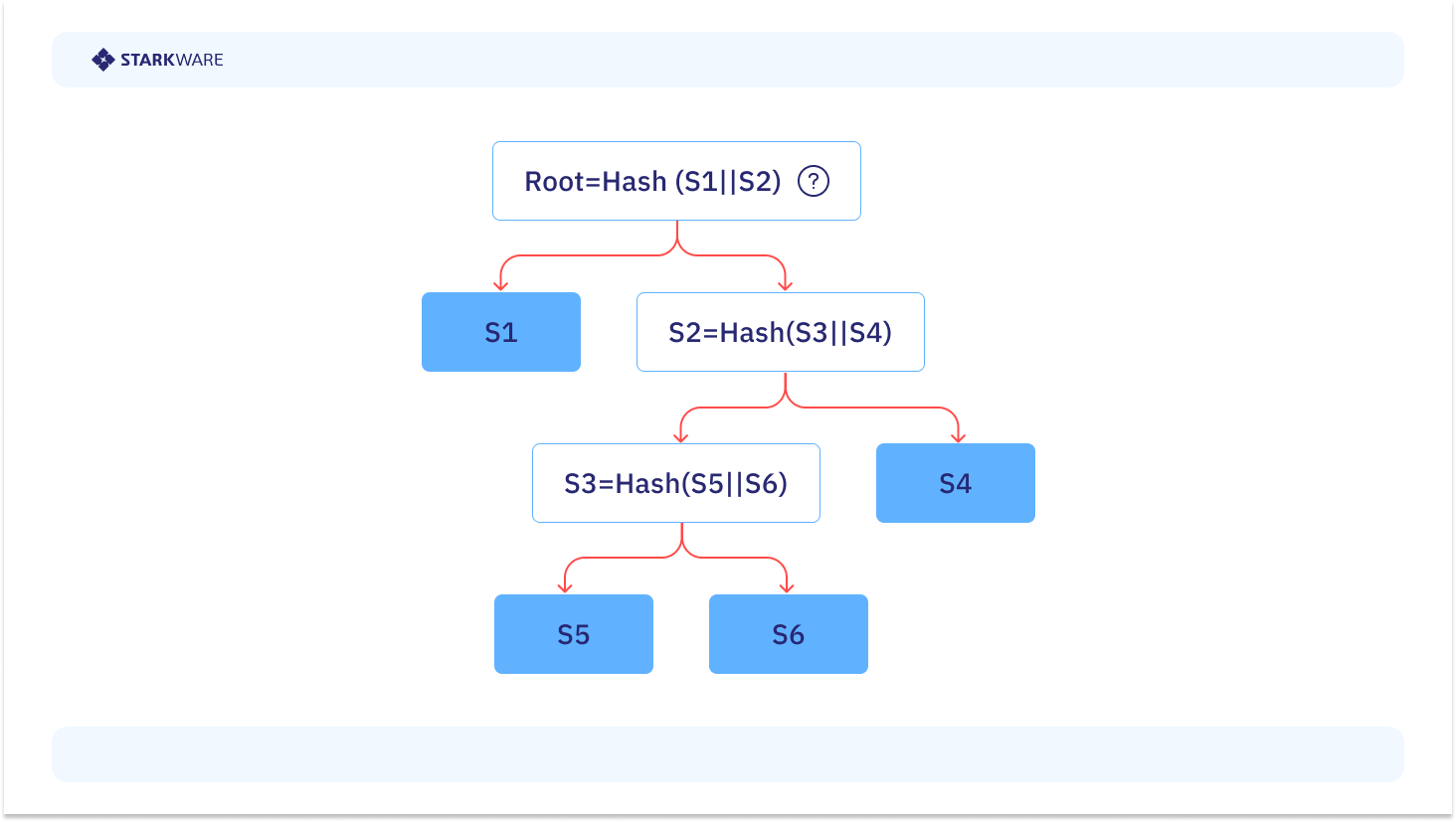

As discussed above, OP_CAT is a simple yet currently disabled opcode that allows Bitcoin script to concatenate elements on the stack. The importance of this simple operation cannot be overstated, as it simultaneously enables both Covenants and STARKs on Bitcoin. Specifically:

-

STARK—This is actually unsurprising. STARKs essentially involve concatenating data and then hashing it. Since hashing is natively supported in Bitcoin script (unlike algebraic operations), this results in significant cost savings. Key hashing operations in STARKs include Merkle path verification (see Figure 8) and the Fiat-Shamir transform. (Additionally, the Circle-STARK variant uses only 31-byte fields, complying with Bitcoin script’s 4-byte limit, making it especially Bitcoin-friendly.)

-

Covenant—In 2021, Andrew Poelstra proposed a remarkable insight that OP_CAT can implement Covenants on Bitcoin using what he calls the Schnorr trick, where Schnorr signatures are the digital signatures used in Pay2Taproot output types (for other types, a similar ECDSA trick observed by Robin Linus can be used). Briefly, to implement Covenants, we need to use OP_CHECKSIG—the only opcode capable of placing data related to the spender’s transaction onto the stack. This process isn’t trivial, but with some manipulation, all necessary data becomes accessible.

Regarding the last point, maintaining state in Pay2Taproot outputs involves certain technical challenges. However, other output types like Pay2WitnessScriptHash can be used to store state. This leads to the “state caboose” technique illustrated earlier in Figures 4 and 5, where transactions contain two outputs.

Figure 8: *Merkle path verification, involving hash and string concatenation operations. Parts of the Merkle path (blue strings) are concatenated and hashed accordingly. Then, equality with the Merkle root is checked. The OP_CAT operation is denoted as ||.*

8. Current Status and Future Outlook

Within the open-source initiative led by Weikeng Chen and Pinghzou Yuan, we are jointly building the Bitcoin Wildlife Sanctuary. Two main projects include:

-

Circle-STARK verifier, whose working demo can verify a STARK proof for a simple statement on Bitcoin Signet (related to Fibonacci numbers). You can track its progress via this address.

-

Covenant framework, already applied in a simple counter Covenant. The verifier also uses this framework.

Through these efforts, our goal is to bring efficient, secure, and developer-friendly OP_CAT smart contracts to Bitcoin. We believe this represents a promising and exciting prospect for Bitcoin computation.

9. Conclusion

In summary, through this article we have learned:

-

Covenants are a powerful tool within Bitcoin script, enabling smart contracts on Bitcoin. Covenants expand Bitcoin’s functionality beyond simple value transfers.

-

However, even with Covenants, Bitcoin script still faces many limitations—including stack size caps and restricted opcode types—limiting the complexity and expressiveness of smart contracts achievable with Covenants alone.

-

STARKs offer a promising solution to mitigate these limitations by efficiently verifying off-chain computation. Leveraging STARKs enables more complex computations within Bitcoin smart contracts while minimizing on-chain computational overhead.

-

Cairo is a programming language designed specifically for efficient proving and verification using STARKs, making it highly suitable for Bitcoin smart contracts. It enables creation of more complex contracts, enhancing usability, functionality, and security.

-

OP_CAT is a Bitcoin script opcode for concatenating elements. OP_CAT plays a crucial role in enabling both Covenants and STARKs on Bitcoin, thereby unlocking powerful general computation capabilities on Bitcoin.

In our next article, we will dive deeper into the Circle-STARK verifier on Bitcoin.

Thanks to Weikeng Chen, Pingzhou Yuan, and the StarkWare team for their valuable feedback on this article.

Victor Kolobov

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News