Placeholder: Thinking About Stablecoin Growth Potential from the Perspective of Currency Hierarchy

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Placeholder: Thinking About Stablecoin Growth Potential from the Perspective of Currency Hierarchy

The innovative aspect of stablecoins is not the currency, but the technology and distribution.

Author: Mario Laul

Translation: Luffy, Foresight News

The core function of blockchain networks is to securely process and maintain timestamped records of information. In principle, blockchains can record any type of data, but most typically they track financial balances and transactions. The simplest and most common financial transaction is a payment. While current blockchains serve multiple use cases, transferring units of value—such as paying for goods or services—remains the foundational use case across all major networks. However, while successful blockchains have become dominant payment networks in certain niche markets, their broader success in large-scale everyday payments usually stems from stablecoins pegged to fiat currencies.

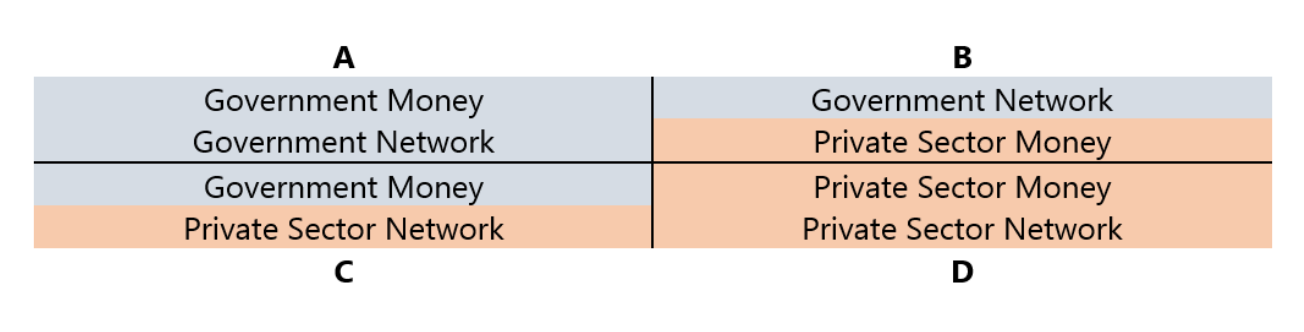

Monetary and payment systems can be public or private. “Public” refers to governments, central banks, and other public-sector institutions, whereas “private” denotes privately owned and operated entities such as most commercial banks, credit card companies, and other financial service providers. In practice, the boundary between the two is not as clear-cut as shown in the quadrant below, since publicly issued money circulates on private networks, and many private financial institutions are heavily regulated by public authorities. Nevertheless, the public-private distinction serves as a useful starting point for understanding how emerging monetary and payment systems relate to existing ones.

The table below is explained and illustrated in two ways: (1) covering all monetary units of account, and (2) within government-defined units of account, typically tied to national currencies.

In the first scenario, a currency is truly “private” only if it is issued by a private-sector entity, uses a unit of account different from that defined by the government, and transacts on a settlement network independent of government control. Freely floating cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum fall into this category of private money, although their use as units of account and mediums of exchange remains quite limited—for example, paying blockchain transaction fees, or purchasing NFTs and other blockchain-native goods and services. Given the strong network effects of national currencies, non-cryptocurrency private monies see similarly limited adoption in daily payments.

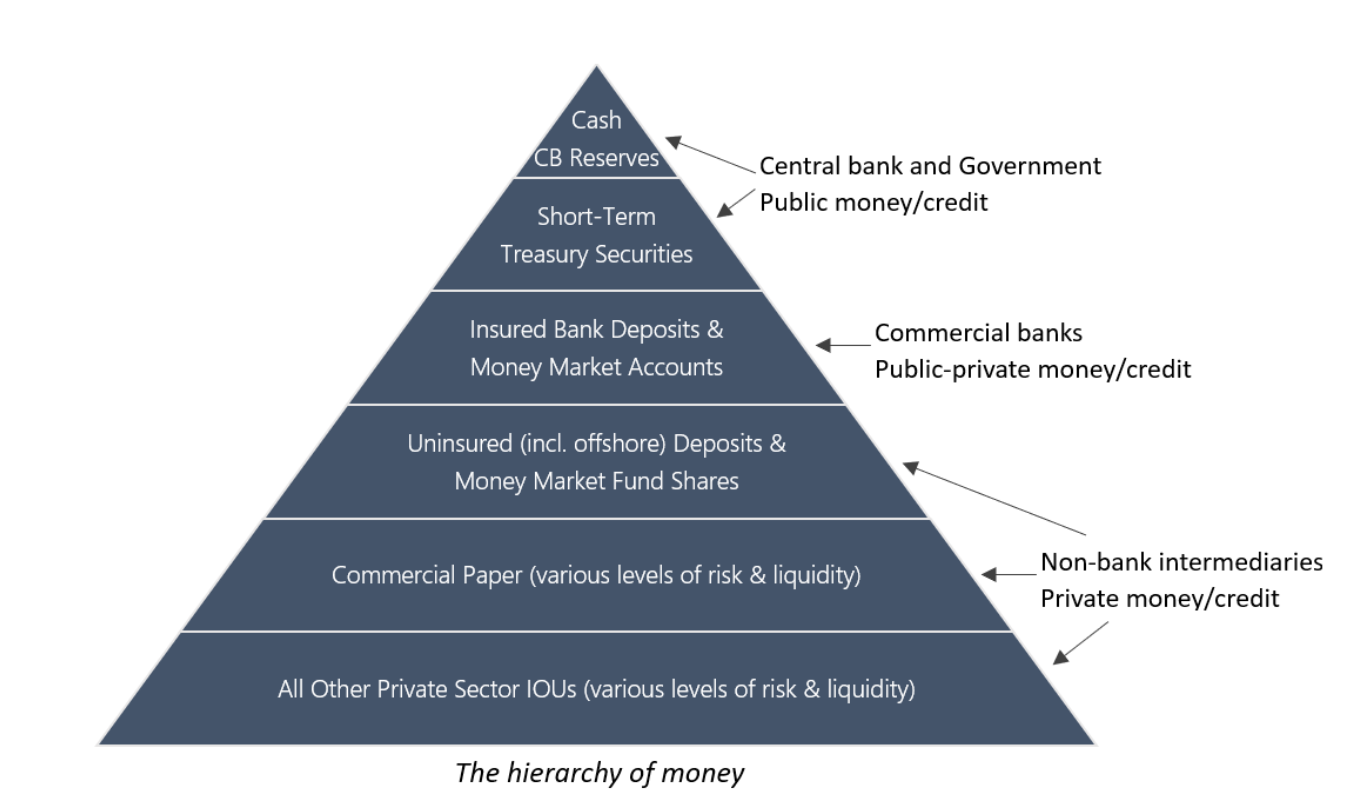

In the second scenario, currencies linked to national money can take more “public” or more “private” forms. This can be illustrated through the classic monetary hierarchy, where acceptability and liquidity decrease from top to bottom: the most widely accepted and liquid (public) money sits at the top of the hierarchy, while the least accepted and liquid (private) money resides at the bottom. Although regional and historical variations exist, the diagram below broadly reflects the situation in most modern economies, where the right to issue currency is restricted to central banks. Yet units denominated in that currency are used by commercial banks, non-bank financial intermediaries, and private entities to price credit and securities, which are treated as cash equivalents to varying degrees.

Although the most widely adopted private currencies—including freely floating cryptocurrencies—may develop their own independent monetary hierarchies, national currencies and their hierarchies dominate global payment use cases. This matters for blockchain because its success as a large-scale payment network appears increasingly less tied to private cryptocurrencies and more closely aligned with a special set of cryptocurrencies operating within the same monetary hierarchy as government-issued money. These are known as stablecoins—cryptocurrencies designed to track the market value of other assets. At the time of writing, the most common anchor asset for stablecoins is the world’s most liquid fiat currency—the U.S. dollar. As a result, most stablecoins effectively belong within the U.S. Federal Reserve System’s monetary hierarchy.

Payment networks serve diverse retail and institutional customer bases and use various settlement instruments (e.g., private IOUs, commercial bank deposits, central bank reserves), existing across multiple layers of the dollar hierarchy. For instance, large-value interbank transactions are processed via Fedwire and the Clearing House Interbank Payments System (CHIPS), while small-value transactions such as utility bill payments or peer-to-peer transfers of commercial bank deposits are handled by the Automated Clearing House (ACH). The most popular point-of-sale payment method is debit/credit cards, typically issued by banks and often integrated with mobile payment apps. Currently, the largest networks processing these payments are operated by publicly traded companies such as American Express, Mastercard, and Visa. Finally, payment gateways like PayPal, Square, and Stripe provide merchants with convenient access to these systems, abstracting away much of the complexity involved in connecting different components.

At each level of the monetary hierarchy, control over payment networks includes the power to decide what qualifies as acceptable payment. This is why accounting conventions matter so much. Generally, as one moves down the hierarchy, “issuing money” becomes easier, but getting others to accept it becomes harder. On one hand, physical cash and commercial bank deposits are nearly universally accepted as payment, but the ability to issue them is strictly regulated. On the other hand, virtually anyone can freely issue private debt, but such IOUs function as money only in very narrow contexts—like gift cards or loyalty points issued by specific companies. In short, not all forms of monetary payment are equal.

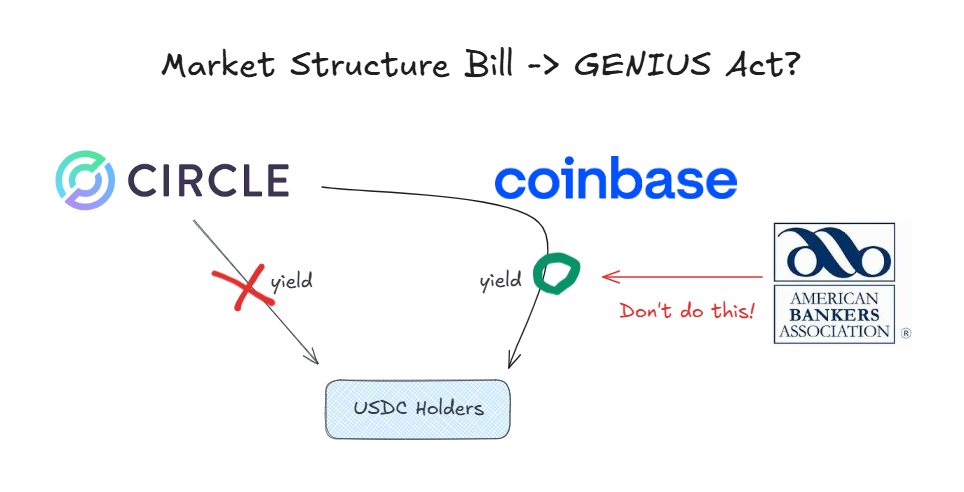

Where do dollar-denominated stablecoins settled on blockchain networks fit into this framework? From the perspective of the monetary unit, dollar stablecoins arguably reside in quadrant C of the chart above. Although stablecoins are issued by the private sector, they are not truly private currencies like Bitcoin or Ethereum due to their peg to the U.S. dollar. This is especially true for stablecoins backed by U.S. dollar deposits or cash equivalents (or even physical commodities) held by regulated U.S. financial institutions, placing them slightly higher in the hierarchy compared to stablecoins backed by offshore assets. Still, both ultimately fall under the same broad category, ranking below insured bank deposits. Stablecoins fully backed by freely floating cryptocurrencies represent a special case due to their low integration with the existing financial system. However, when explicitly designed to maintain a dollar-pegged value, these stablecoins still belong in quadrant C.

From the standpoint of a government-defined unit of account (the dollar), anything other than physical currency and reserve balances held by the central bank constitutes liabilities of private-sector entities, and thus can be classified as “private” money. From this viewpoint, given that all such liabilities—including stablecoins—also circulate on payment networks operated by the private sector, they could be said to reside in quadrant D. While there are important quality differences among stablecoins—depending on the jurisdiction of the issuer and its primary banking partners—the growing notion that “on-chain is the new offshore” highlights similarities between stablecoins and offshore dollars (i.e., Eurodollars), which are not directly regulated by U.S. authorities. But even when stablecoin-backed assets are held by U.S.-regulated financial institutions, from the holder’s perspective they still represent dollar-denominated liabilities without the government guarantee provided by deposit insurance on commercial bank deposits. While counterparty and financial risks vary across specific stablecoins, this ultimately places them in the same category as other privately issued, dollar-denominated debt instruments that lack guarantees yet are still treated as money.

However, stablecoins possess one unique feature: they are issued on decentralized, programmable blockchains. This means anyone with an internet-connected device can register a self-custodied digital wallet without permission, receive peer-to-peer transfers globally at very low cost, and access blockchain-based financial services. In other words, the innovation of stablecoins lies not in the money itself, but in the technology and distribution model. Due to their native digitization, global reach, and programmability, stablecoins have the potential to become a more powerful and convenient form of digital cash than any current alternative. What stands in the way of realizing this potential? Consider three possible adoption scenarios for stablecoins in everyday payments:

Niche / Marginalized

Stablecoins see the highest adoption in certain niche markets—both crypto-native and traditional—and in exceptional circumstances such as currency crises or regions with severely underdeveloped or dysfunctional financial infrastructure. However, they remain marginal in global everyday payments. In most developed economies, existing payment methods such as debit/credit cards, non-crypto mobile wallets, and even physical cash are highly convenient and reliable, leaving little demand for alternatives. Without sufficient consumer demand pulling stablecoin payments into broader economic activity, widespread adoption may stall—especially if stablecoins face unfavorable regulatory treatment in key jurisdictions, hindering their role as substitutes or complements to traditional bank deposits.

Mainstreaming / Convergence

As stablecoins become tightly integrated with existing payment infrastructure, blockchain-based financial services and traditional finance gradually converge. Regulatory clarity around crypto-supportive policies attracts established financial institutions—particularly banks—to issue or otherwise support stablecoins, thereby increasing trust in the underlying blockchain. As the line between stablecoins and traditional bank accounts blurs, a unified regulatory framework eventually emerges, embedding increasingly automated compliance systems and solidifying blockchain’s role as a foundational component of global financial infrastructure. Major stablecoin issuers become significant financial institutions, though their risk profiles vary based on architecture and regulatory status. Thus, during a major financial crisis, some of these entities may face distress, presenting challenges similar to those faced by governments and central banks after the 2007–2008 global financial crisis—further reinforcing their roles as lenders and market makers of last resort. Meanwhile, blockchain’s transparency and programmability enhance the stability and resilience of the financial sector, paving the way for future reforms in national monetary systems and ultimately leading to central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) managed either by governments or through public-private partnerships.

Replacement / Disruption

Stablecoins and blockchain-based financial services evolve in parallel to, rather than integrated with, the existing financial system. Over time, blockchain is increasingly seen not as a complementary layer but as a systemic alternative, directly competing with and eventually replacing traditional systems. While incumbent institutions may adapt by launching their own blockchains, many will find themselves competing against more native crypto counterparts. Given the unique features and risk profiles of blockchain-based financial services, most jurisdictions will prefer creating entirely new regulatory frameworks rather than attempting to fit them into existing rules. While stablecoins pegged to national currencies remain the dominant form of on-chain payment, eventually cryptocurrencies emerge that are not tied to existing currencies but can maintain sufficiently stable exchange rates against a basket of consumer goods. In the long run, the most disruptive outcome would be the widespread adoption of such cryptocurrencies in everyday commerce and even international trade, giving rise to an entirely new monetary system—one that would also require a new global monetary governance institution.

Historically, most cryptocurrencies have exhibited significant price volatility, making them unsuitable as units of account or general-purpose payment media. Stablecoins solve this problem and are arguably one of the most successful use cases of blockchain to date. While tokens specific to certain networks and applications hold important utility for operators, developers, and administrators, their adoption threshold for everyday payments is significantly higher than that of stablecoins pegged to off-chain currencies already familiar to consumers. Therefore, regardless of which of the above scenarios unfolds, the growth of blockchain as a payment network remains deeply intertwined with the success of stablecoins.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News