Deep Dive into EigenLayer Intersubjective Staking: Intersubjectivity, Tyranny of the Majority, and Forkable Work Tokens

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Deep Dive into EigenLayer Intersubjective Staking: Intersubjectivity, Tyranny of the Majority, and Forkable Work Tokens

Preventing tyranny of the majority through the social consensus power brought by forkable work tokens.

Author: @Web3Mario

Introduction

During the May Day holiday, EigenLayer released the whitepaper for its EigenToken. Strictly speaking, this is not a traditional economic whitepaper aimed at introducing incentive models or value accrual mechanisms. Instead, it presents an entirely new business system—Intersubjective Staking based on the EigenToken. After reading the full whitepaper (without diving deeply into the appendices) and reviewing interpretations by others, I’ve formed some personal insights and understanding that I’d like to share, and I welcome further discussion. Let me state my conclusion upfront: I believe the significance of Intersubjective Staking lies in proposing a consensus system built upon a forkable ERC-20 token model, capable of making decisions on matters involving "intersubjective group judgment" while avoiding the tyranny of the majority.

What Is “Group Subjectivity”?

Correctly understanding Intersubjective is key to grasping the significance of this system. As for how to translate this term, there seems to be no consensus yet within Chinese-language internet communities. After reading an article by Professor Pan Zhixiong, I found his perspective compelling—the concept of "social consensus" does indeed offer a solid framework for understanding its meaning. However, I feel that using “group subjectivity” better aligns with the literal translation and aids clarity, so throughout the rest of this piece, I will use “group subjectivity” to refer to Intersubjective.

What exactly is “group subjectivity”? In the context of EigenLayer, it refers to a broad consensus among all active observers within a given system regarding whether the outcome of a certain task execution is correct or incorrect; when such consensus exists, we say the task exhibits intersubjectivity—or group subjectivity. We know one of EigenLayer’s core values lies in decoupling the consensus layer from the execution layer, focusing instead on building and maintaining the former, thereby turning consensus into a service and reducing development costs for Web3 applications while unlocking latent market demand. In its narrative, EigenLayer positions itself as a decentralized digital public platform capable of executing digital tasks for third parties. It naturally becomes necessary, then, to define the boundaries of its services—specifically, which types of digital tasks can be executed in a “trustworthy” manner. Within the Web3 context, “trustworthiness” typically means a system uses cryptographic design or economic models to prevent errors during task execution. Therefore, the first step is to classify possible error types in digital task execution. EigenLayer divides these errors into three categories:

Objectively Attributable Errors: These are errors that can be proven via a set of objectively verifiable evidence—typically on-chain data, or data with Data Availability (DA)—using logical or mathematical reasoning, without relying on trust in any specific entity. For example, if a node on Ethereum signs two conflicting blocks, this error can be cryptographically proven. Similarly, fraud proofs in Optimistic Rollups involve re-executing disputed data on-chain to verify correctness through result comparison.

Group-Subjective Attributable Errors: These are errors where all participant groups within a system share a common subjective standard for judging the correctness of a digital task’s outcome. This category can be further divided into two subtypes:

* Errors identifiable at any time by reviewing historical data—for instance, if a price oracle reports the spot price of BTC on Binance at $1 at 00:00:00 UTC on May 8, 2024, this error can be detected retroactively at any point.

* Errors only detectable through real-time observation—such as malicious censorship, where a transaction is persistently rejected by a group of nodes.

Non-attributable Errors: These refer to execution errors over which there is no established, widely accepted judgment standard among participants—e.g., determining whether Paris is the most beautiful city.

Intersubjective Staking aims precisely to effectively resolve digital tasks exhibiting group subjectivity—meaning it can handle group-subjectively attributable execution errors. In this sense, it represents an extension of on-chain systems.

The Tyranny of the Majority in Current Solutions

The “tyranny of the majority” is a political term referring to a situation where a supermajority in a legislative body forcibly passes policies that harm minority interests. With EigenLayer’s goals clarified, let us now examine current approaches to addressing such issues. According to EigenLayer’s analysis, they fall into two main types:

1. Penalty Mechanisms: These rely on cryptoeconomics to deter malicious behavior by slashing staked funds from misbehaving nodes. One such method is staking slash. However, this approach faces a critical flaw: imagine an honest node submits proof of wrongdoing, but most other nodes collude to act maliciously—they may simply ignore the proof or even retaliate by penalizing the honest node.

2. Committee-Based Mechanisms: These designate a fixed group of committee nodes to validate the accuracy of misconduct proofs in case of disputes. Yet this raises major concerns about trustworthiness—if committee members collude to act maliciously, the entire system collapses.

Both solutions clearly suffer from the problem of majority tyranny. This highlights the core challenge: although there may be widespread agreement on what constitutes a correct outcome, the lack of objective verification forces reliance on human judgment rather than cryptographic or mathematical certainty. When the majority chooses to act maliciously, existing mechanisms become powerless.

Avoiding Majority Tyranny Through Forkable Work Tokens and Social Consensus

So how does EigenLayer solve this problem? The answer lies in designing a forkable on-chain work token and leveraging the social consensus capability derived from staking this token to manage group-subjective digital tasks and avoid the tyranny of the majority.

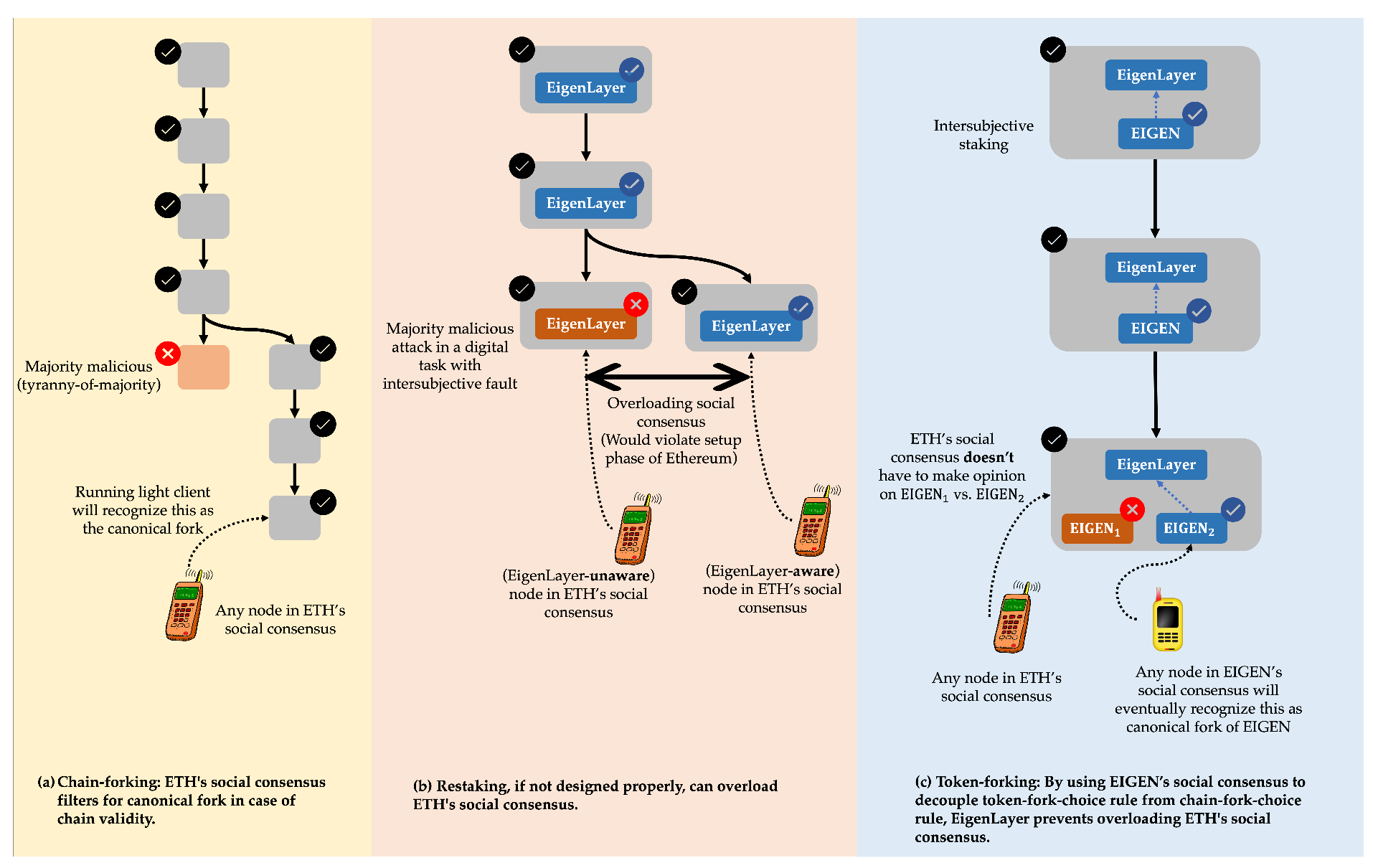

But what exactly is this so-called “social consensus capability” enabled by forkability, and how does it prevent majority tyranny? First, EigenLayer draws inspiration from research on Ethereum’s PoS consensus. It argues that Ethereum’s security stems from two sources:

* Cryptoeconomic Security: By requiring block producers to stake capital and implementing penalties for malicious behavior, the system ensures that the cost of cheating exceeds potential gains, thus deterring bad actors.

* Social Consensus: When malicious actions cause a chain split, users who share a common standard for judging correctness can subjectively evaluate different forks and choose the one they believe is valid. Even if malicious nodes control the majority of staked capital, widespread user abandonment of the malicious fork can lead its value to decline while the legitimate fork regains dominance. For example, most centralized exchanges would support the correct fork—even if backed by less stake—and reject the incorrect, heavily staked malicious fork. Over time, due to broad social consensus, the malicious chain loses value, and the alternative fork emerges as the “canonical chain.”

We know that blockchain’s essence is achieving consensus on the order of transactions within a trustless distributed system. Ethereum builds on this by introducing a serial execution environment—the EVM—ensuring consistent results whenever transaction order is agreed upon. EigenLayer notes that evaluations of such execution outcomes are mostly objectively attributable but also include cases of group-subjective attributability. Specifically, this pertains to assessments along the dimension of Chain Liveness. In Ethereum’s PoS consensus, there exists a special mechanism called Inactivity Leak: when more than one-third of validators fail to produce blocks correctly due to unforeseen circumstances (e.g., war causing regional internet disconnection), cryptoeconomic security breaks down. In response, the network enters Inactivity Leak mode—no inflation rewards are issued for new blocks, and inactive validators gradually get slashed until the active stake once again exceeds two-thirds. This allows both forks to eventually regain independent cryptoeconomic security.

Afterward, deciding which chain becomes the “canonical fork” depends entirely on users exercising their own judgment—a process known as “social consensus.” As users make active choices, the value accumulated on each fork shifts, until one clearly prevails under competitive cryptoeconomic pressure. This process can be seen as security conferred through social consensus.

Summarizing this phenomenon, EigenLayer observes that Ethereum relies on social consensus to identify and resolve intersubjective errors related to chain consistency—such as liveness attacks. The core of this social consensus capability lies in forkability: rather than immediately determining which side is malicious when disagreement arises, the system allows subsequent user choice—“voting with their feet”—to resolve conflicts via collective judgment. This avoids protocol-level majority tyranny because a small number of honest nodes aren’t instantly penalized by collusion, giving them a chance to recover. This method proves valuable precisely in handling problems involving group subjectivity.

Therefore, guided by this insight, EigenLayer adapts and enhances the consensus model of Augar—an on-chain prediction market protocol—to introduce a forkable on-chain work token called EIGEN. Around EIGEN, it designs an Intersubjective Staking mechanism to achieve consensus on the execution of group-subjective digital tasks. When disagreements arise over execution outcomes, the system enables a fork of EIGEN and resolves the conflict over time through emerging social consensus. The underlying technical details aren’t particularly complex and have already been explained in other articles, so I won’t elaborate here. I believe that once the above relationships are understood, one can grasp the significance and value of Eigen’s Intersubjective Staking fairly well.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News