The popularity of Runes is a step backward in cryptographic technology development, yet it best embodies the core values of Web3.

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The popularity of Runes is a step backward in cryptographic technology development, yet it best embodies the core values of Web3.

Innovation around digital assets will continue to be the core driving force of Web3.

Author: @Web3Mario

Introduction: Yesterday, I accidentally learned from a friend about their substantial investment return in the BTC ordinals space, which deeply triggered my fear of missing out (FOMO). I felt anxious for two consecutive days—an admittedly embarrassing reaction.

Recalling earlier times, shortly after the Ordinals technical architecture was first released, I studied its documentation. But as a developer, I initially dismissed this technological path—my judgment at the time was that it represented a step backward for cryptographic technology. Its design philosophy seemed reminiscent of an obscure altcoin project called Color Coin: essentially, how to issue independent tokens using BTC's existing architecture. The key difference is that Ordinals does not build a new chain but instead reuses the already widely-consensual Bitcoin network.

Compared with the proposal of on-chain virtual machines (e.g., EVM or WASM), this architecture has been proven rather rudimentary and non-scalable. Due to Bitcoin lacking a Turing-complete execution environment, application-layer development is relatively difficult—and expensive! Even after the so-called canonical Runes protocol was announced, I remained unimpressed upon reading its documentation. It merely defined certain standards to make BRC-20 appear less crude—something utterly trivial within virtual machine-based blockchain designs, where creating an ERC-20 token is something even a beginner Web3 developer can accomplish... Yet all these judgments now seem laughably pale when confronted with real wealth effects. After calming down, I’d like to share some reflections with you.

The tangible fact at the root of all our thought-distinctions, however subtle, is that there is no one of them so fine as to consist in anything but a possible difference of practice. To attain perfect clearness in our thoughts of an object, then, we need only consider what conceivable effects of a practical kind the object may involve—what sensations we are to expect from it, and what reactions we must prepare.

----William James

Anarchist, Post-Snowden Web3

Many of my friends marvel at Bitcoin’s emergence as if it were akin to the golden age of ancient Greece—an inexplicable genius product. However, I disagree. I believe Bitcoin’s invention was not accidental but rather an inevitable outcome of the network environment at that time.

As previously discussed, we’ve reviewed the evolution of the Web. During the classical liberal internet era, principles of openness, inclusivity, globalization, and neutrality gradually shaped internet protocol design. However, with the proliferation of web applications, the composition of internet users drastically changed—from a subculture of user-developers to a universal mainstream audience. Pragmatism, prioritizing efficiency and low cost, gained dominance.

This did not mean the principle of open protocols vanished entirely. Unlike political revolutions, technological evolution is non-violent, making ideological progression a gentle, integrative process. In fact, a group of developers—whom we might call remnants of classical liberalism—have consistently upheld open protocol principles in both technological research and conceptual advocacy. We can easily identify them: organizations such as the Free Software Foundation, Electronic Frontier Foundation, and Wikimedia Foundation have successively funded and promoted many intriguing technologies like Tor, VPNs, and SSH. These same groups were also among the earliest adopters of Bitcoin, using it for fundraising. Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that Bitcoin’s design originated from this community, with the initial goal being the creation of a regulatory-resistant, anonymous electronic cash system for payments.

Bitcoin’s tremendous success subsequently attracted the interest of some computer scientists—I believe Vitalik and Gavin Wood belong to this cohort. Leveraging Bitcoin’s most original innovation—the Proof-of-Work (PoW) consensus algorithm—they envisioned building a decentralized, anonymous computing system, thereby fundamentally transforming the classic client-server (C/S) web development paradigm.

Amid the explosive revelation of the "PRISM scandal," both technological and political authorities suffered severe credibility loss, creating fertile ground for promoting new concepts. This context gave rise to the latest semantic iteration of Web3—Gavin Wood’s version of Web3. Here, I find it necessary to once again quote his classic definition:

Web 3.0, or as might be termed the “post-Snowden” web, is a re-imagination of the sorts of things we already use the web for, but with a fundamentally different model for the interactions between parties. Information that we assume to be public, we publish. Information we assume to be agreed upon, we place on a consensus ledger. Information that we assume to be private, we keep secret and never reveal. Communication always takes place over encrypted channels and only with pseudonymous identities as endpoints; never with anything traceable (such as IP addresses).

The core vision of this version of Web3 is to build a de-authoritized, censorship-resistant network world that fully protects personal privacy—a classic interpretation of anarchism within cyberspace. Hence, I refer to it as Anarchist Web3. Notably, making this distinction clear is crucial because we must understand which principles should guide our application design in order to best fulfill our ultimate aspirations.

Guided by this ideology, the extreme pursuit of decentralization and privacy has spawned a series of fascinating Web3 projects. Successful cases in this category are typically foundational infrastructure projects. Recall the sophisticated cryptography and consensus algorithms—no need for specific examples, as numerous renowned projects fit this mold. However, at the application and protocol layers, such successes are far fewer, with perhaps ENS being a notable exception.

Hyper-Financialized Liberal Capitalist Web3

Since 2013, when Mastercoin introduced the ICO crowdfunding model, crypto-based crowdfunding gradually gained popularity. With the maturation of protocol-layer standards like ERC-20, the barriers to issuing and participating in tokens were greatly reduced, culminating in the ICO boom of 2017.

Let us revisit that period. The coin (or token) as an asset evolved into various types, the most representative being utility tokens and ownership tokens. The former function like admission tickets—only holders gain access to use the target project. In the early days of ICOs, most issued tokens fell into this category, including Mastercoin, NextCoin, and even Ethereum (whose initial design did not include PoS planning).

The emergence and rapid growth of ownership tokens, I believe, stemmed from two key opportunities. The first was the introduction of Proof of Stake (PoS) by a hacker named Sunny King in 2012, along with the development of Peercoin. This concept’s greatest contribution was proposing a paradigm where tokens represent ownership of a dedicated network (though here, tokens primarily conveyed dividend rights). This sparked widespread interest in network ownership models, peaking during EOS’s ICO in 2018. However, excessive speculation and the failure to deliver promised applications led to stagnation.

The second major opportunity for ownership tokens traces back to Compound launching COMP, which truly ushered in the era of hyper-financialized liberal capitalist Web3. Prior to this, ownership token development focused almost exclusively on allocating ownership of base-layer networks, while application layers remained largely unresponsive. In fact, many well-known DApps were created quite early, yet the dominant model remained “admin governance” plus “pay-to-use.” Only after COMP’s launch did the model of using tokens to represent application ownership—enabling “community governance” and “mining incentives” tied to DApp usage—gain broad recognition and accelerate rapidly. Generous financial returns, smooth exit mechanisms, and a free-market environment attracted massive investor capital into Web3. Similar to the transformation of classical liberal networks, the industry underwent another shift driven by changing user demographics. The meaning of Web3 itself transformed significantly. Let’s recall Chris Dixon’s definition:

Web3 is the internet owned by the builders and users, orchestrated with tokens. In web3, ownership and control is decentralized. Users and builders can own pieces of internet services by owning tokens, both non-fungible (NFTs) and fungible.

By now, the distinction is clear. Web3 had shifted from pursuing de-authoritization and personal privacy toward using digital assets to represent network ownership, enabling redistribution of network resources. Under this vision, private ownership of digital assets and an absolutely free market became the ultimate goals, while de-authoritization and privacy degraded into mere means to achieve those ends. This marks a significant transformation—one essentially equivalent to the political ideals of liberal capitalism (indeed, in political philosophy, liberal capitalism closely aligns with a specific form of anarchism).

Guided by this ideology, innovation in the categories of value represented by digital assets and methods of ownership distribution became the primary evolutionary direction. Essentially, until the recent intense deleveraging wave, most Web3 innovations centered around this axis. We must clearly distinguish between these two ideologies, as they lead to entirely different evaluation criteria. A Web3 project deemed excellent by supporters of Anarchist Web3 may seem meaningless to adherents of liberal capitalist Web3, and vice versa. Ultimately, this divergence stems from ideological differences.

Innovation Around Digital Assets Will Continue to Drive Web3 Forward

Having clarified the differences between these two paradigms, I wish to explore what might drive the next wave of rapid Web3 development. Personally, I lean toward pragmatism. To me, the significance of any idea or concept lies in its practical impact—how it influences human behavior and creates value. Top-down metaphysical reasoning often hinders social progress. From this perspective, I also find socialism compelling.

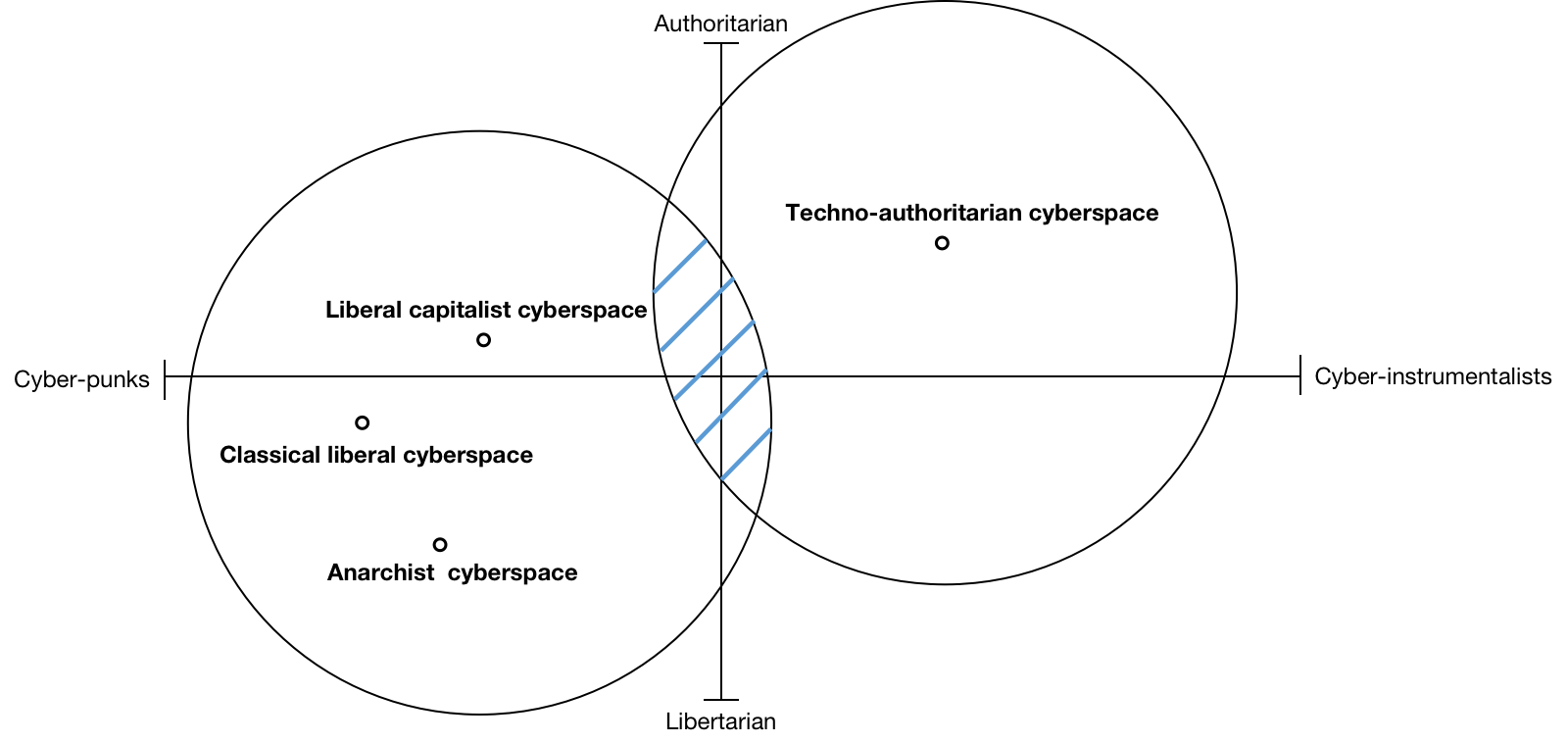

Under this worldview, I believe the digital world will likely evolve along a pragmatic, low-friction path. Recall the ideological spectrum of the internet we discussed earlier—we can broadly categorize classical liberal internet, Anarchist Web3, and liberal capitalist Web3 under the same ideological cluster, positioned opposite to technocratic authoritarianism. Future energy in the networked world will emerge more vigorously within this blue-shaded region. The driving force behind this evolution hinges on whether new, more universally applicable value propositions can be discovered. Based on existing achievements, I believe digital assets inherently possess such potential—or rather, innovation围绕digital assets will continue to serve as Web3’s core engine.

First, let me clarify: I do not deny the value of work related to decentralization and privacy protection. On the contrary, I find such efforts often profoundly insightful. However, given current realities, achieving these two goals usually depends on advances in cryptography. Constrained by the pace of technological development, products built under this philosophy often perform poorly—there remains significant room for improvement compared to mature computer networking technologies. Moreover, since cryptography is a fundamental discipline requiring high investment and long development cycles, it conflicts with the current operational realities of most Web3 companies. I don’t foresee this situation changing soon.

However, discussions around digital assets present a different picture. To this day, I remain amazed by the elegance of digital asset (or crypto asset) ownership design in the Web3 world. Its direct impacts manifest in three aspects:

• A method of ownership verification relying solely on technology;

• A method ensuring owners’ exclusive control over digital assets in digital form;

• A network-based method for transferring digital assets;

Without exaggeration, no prior technical solution or product has realized digital assets as perfectly as Web3. This perfection grants Web3 digital assets greater practical value—high liquidity and low-cost trust establishment—injecting fresh vitality into the development of the digital world. Therefore, I believe the core driver of the next wave of Web3 growth will continue to be innovation围绕digital assets. Broadly speaking, such innovation may unfold in the following directions:

* Paradigm Innovation: Similar to FTs and NFTs, each new digital asset paradigm injects unprecedented momentum into Web3, providing concrete boundaries and guidance for innovation. At first glance, the dichotomy of Fungible and Non-Fungible might seem sufficient to cover all asset types. But I argue this is incorrect—just as gender was long assumed to be binary, only for us to later recognize a broader spectrum. Similarly, I find it intriguing to propose token paradigms with context-dependent characteristics. Fungibility is just one dimension; many others await discovery. Of course, for such innovations to be meaningful, they must be tied to specific use cases. Recently, the introduction of new digital asset carriers like Runes strikes me as a very promising start;

* Value Innovation: By combining existing FT and NFT paradigms with novel economic models or application designs to represent new types of value—this is another highly meaningful frontier. Taking FTs as an example, the values they currently embody can generally be abstracted into four categories: utility value, growth value, dividend rights, and governance rights. In upcoming articles, I will analyze the distinctions among these four types in detail. Given current industry trends, credit value could emerge as a fifth dimension, complementing the existing framework.

* Business Model Innovation: This type of innovation typically targets specific business challenges, attempting to solve old problems with new approaches for better outcomes. I see two particularly promising paths: First, transforming traditional internet businesses by leveraging certain characteristics of digital assets to partially optimize or overhaul existing models, thus forging new competitive advantages. Second, optimizing or reinventing current models of digital asset usage—also known as tokenomics innovation. Such innovations often act as catalysts for industry growth, with examples including Yield Farming and X-To-Earn models.

In conclusion, although protocols like Runes may appear technically regressive, as new digital asset carriers, their value still deserves recognition. What shape the future of Web3 will ultimately take—let us wait and see.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News