The Power of Zero-Knowledge Proofs: Privacy-Driven Innovation in a Decentralized World

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Power of Zero-Knowledge Proofs: Privacy-Driven Innovation in a Decentralized World

We've only seen the tip of the iceberg of ZK technology's potential, and its true capabilities are far from being fully realized.

Author: Salus

1. Introduction

Zero-knowledge proof (ZK) technology can address privacy and security challenges in decentralized systems. This article illustrates the critical role of ZK technology through four use cases: DEXs, oracles, voting, and auctions. ZK is used to ensure that transactions on a DEX can be verified while protecting user privacy by concealing identities or other transaction details. Based on ZK, data retrieved from oracles can be guaranteed accurate, preventing tampering during transmission or computation. In blockchain voting projects, eligible voters can cast votes anonymously, and vote integrity can be protected against pre-tampering—another application enabled by ZK. The technology also provides bidders in blockchain auctions with identity privacy protection while addressing issues like bid manipulation.

2. Privacy Risks in the Decentralized World

Blockchains keep no secrets—all information is publicly visible, leading to inherent shortcomings in privacy protection. Additionally, many smart contracts rely on off-chain data, introducing additional security risks. Below, we will examine in detail the security issues and potential threats arising from these two characteristics.

Security Issues Caused by Blockchain's Transparency

Blockchain’s transparency ensures transaction traceability but simultaneously introduces security vulnerabilities. For example, privacy leaks and front-running attacks in DeFi.

Privacy leakage: On-chain addresses can easily be linked to real-world identities using techniques such as address labeling, IP matching of transactions, and broadcast node probing. These analytical methods not only expose user identities but also reveal behavioral patterns and investment strategies. For instance, frequent trading or specific types of transaction activity may disclose a user's investment preferences or habits—information often misused for competitive advantage or improper exploitation.

Front-running: Attackers exploit blockchain transparency to monitor pending transaction queues. By analyzing unconfirmed transactions, they can submit competing transactions with higher fees to incentivize miners to prioritize them. This allows attackers to execute trades before others, gaining unfair advantages. Such behavior distorts fairness in trading, enables market manipulation, and harms other users.

Therefore, DeFi protocol design must fully consider these potential security threats. Additional privacy-preserving measures should be implemented to protect users from identity exposure and transaction pattern analysis.

Security Risks When Blockchains Access Off-Chain Data

Smart contracts cannot directly access off-chain data; they can only read on-chain transaction data or the state of other contracts. Smart contracts are self-executing programs on the blockchain whose outputs must remain consistent across all nodes—that is, identical inputs must produce identical results. Since off-chain data may change over time, direct retrieval by smart contracts could lead to inconsistent execution outcomes across nodes, breaking blockchain consensus.

However, many applications require smart contracts to depend on off-chain data. For example, a DEX needs up-to-date prices for stocks or cryptocurrencies, which typically come from external financial markets or exchanges. To bridge this gap, blockchains use oracles. When a smart contract requires off-chain data, it requests the oracle, which retrieves and returns the data. Oracles can also transmit on-chain data off-chain.

However, introducing oracles creates new security risks, as oracles may provide inaccurate data due to errors or malicious behavior. Therefore, oracle design and implementation must prioritize security.

Blockchain-based voting and auction projects face unique security challenges. While blockchain offers transparency and immutability for voting platforms, ensuring voter eligibility, enabling anonymous voting, and preventing pre-tampering of votes remain difficult. In on-chain auctions, key issues include fake bids and account visibility. If one participant can see another’s balance, they gain an unfair informational advantage.

3. Privacy-Driven Innovation in Use Cases

3.1 ZK Private DEX

Blockchain transparency poses privacy challenges for many DeFi projects. In response, Salus uses DEXs as an example to explore how ZK technology plays a crucial role in enhancing privacy protection.

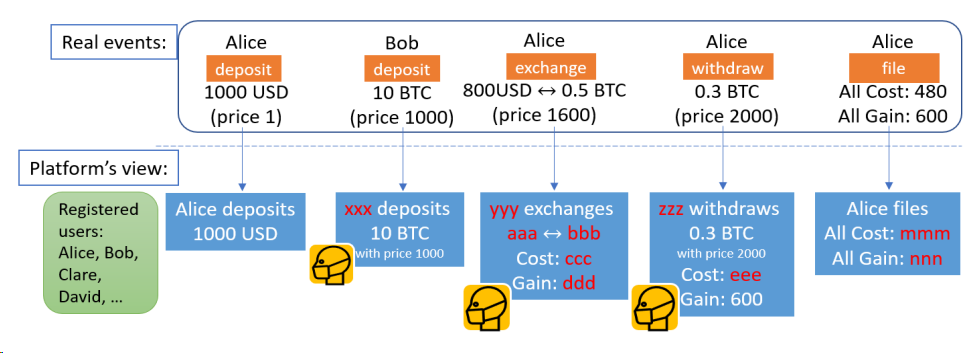

Imagine a private DEX with built-in privacy features. Using ZK technology, it can hide parts of transaction information while still allowing verification of transaction validity. On this DEX, only partial transaction data is public—for example, all registered users, their bank accounts, and the names and amounts of deposits and withdrawals—as shown in Figure 1. Traders know their full transaction history, but cannot view others’ complete records. Consider five specific transaction events:

Figure 1: Private DEXs with only partial public information. Source: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2309.01667.pdf

Assume five transactions occur on this private DEX platform, with corresponding event details as follows:

-

Alice deposits 1,000 USD into the platform.

-

Bob deposits 10 BTC onto the platform when BTC is priced at 1,000 USD.

-

Alice trades 800 USD for 0.5 BTC on the platform when BTC is priced at 1,600 USD.

-

Alice withdraws 0.3 BTC from the platform when BTC is priced at 2,000 USD.

-

The platform records Alice’s total spending and earnings as 480 USD and 600 USD respectively.

This private DEX leverages ZK technology to enable privacy protection, where full transaction details are only visible to involved parties. Instead of revealing full transaction logs, the platform provides privacy-preserving event data. Next, we explain what these private events entail and how they are verified:

-

When depositing 1,000 USD, the bank identifies Alice. She then receives an asset voucher or signature generated by the platform. To prevent double-spending and ensure compliance, the signed message must include attributes beyond basic asset details—such as a unique asset identifier tied to Alice’s user ID. This information must be hidden to preserve anonymity. Alice must use ZK technology to prove her blinded user identifier matches her registration credential. To meet tax-reporting and client-compliance requirements, profit from selling assets and withdrawal transactions must be tracked. Thus, purchase price is included as an additional attribute in the asset voucher.

-

When Bob deposits 10 BTC, the platform does not know his identity, as this is not a fiat deposit.

-

When Alice exchanges 800 USD for 0.5 BTC, she uses her 1,000 USD asset voucher to request two new vouchers—one for the remaining 200 USD and one for 0.5 BTC—while keeping details hidden. The platform approves her request under certain conditions proven via ZK: sufficient USD balance, shared user identifier between vouchers, non-negative remaining USD amount, BTC price aligned with latest rates, and equivalent total value.

-

When withdrawing 0.3 BTC, the process resembles trading, except for the swapped asset. Alice also verifies the receipt of withdrawn BTC on-chain.

-

When total expenditure is 480 and income is 600, Alice presents a valid registration credential with her identity and requests an updated credential with a new index, resetting expenditure and income to zero, and obtains a document credential for regulatory reporting. This document includes Alice’s real identity, correct figures (480 spent, 600 earned), and auxiliary regulatory data. Since expenditure and income are hidden by the platform to prevent leaks, Alice must prove her committed values match those in her registration credential. The platform performs a blind signature. Alice unblinds it and submits the signed message to regulators for tax reporting.

3.2 zkOracle

Consider a blockchain-based agricultural insurance smart contract that determines payouts based on weather data provided by an oracle. For example, if a region suffers severe drought, farmers there receive compensation from the insurance contract.

However, if the oracle incorrectly reports weather conditions—e.g., claiming normal rainfall despite actual drought—this erroneous data leads the smart contract to make incorrect decisions, denying compensation to farmers who genuinely need it.

This example highlights the critical importance of ensuring oracle data accuracy. zkOracle is a trustless, secure oracle built on ZK technology. Below, we compare traditional oracles with zkOracles and explain why ZK technology plays a pivotal role.

Traditional oracles fall into three categories. We compare them along four dimensions:

In this article, we focus on Output Oracle and I/O Oracle. Both derive data from the blockchain, meaning the data has already been validated and secured by the chain. The key issue we discuss is how to ensure the security of computation and transmission within the oracle.

To build a secure oracle, we can apply ZK enhancements to both output oracle and I/O oracle, creating output zkOracle and I/O zkOracle. The following sections compare workflows of traditional oracle, output zkOracle, and I/O zkOracle, explaining where ZK modifications are applied.

1. Traditional Oracle

The workflow of a traditional oracle is illustrated in Figure 2:

Step ①: Retrieve data from source

Step ②: Perform computation on data

Step ③: Output result

Figure 2: Traditional Oracle

ZK enhancements can be applied to Steps ② and ③ of the traditional oracle workflow, leaving Step ① unchanged:

2. Output zkOracle

Step ② - ZK Enhancement: Computation and ZK Proof Generation

The computation module uses ZK technology to process data retrieved from the source—typically performing sorting, aggregation, or filtering—and generates a ZK proof as output. This makes computation and output verifiable.

Step ③ - ZK Enhancement: ZK Proof Verification

The ZK proof generated in Step ② can be verified on-chain via smart contracts or in any environment, confirming the validity of the prior computation.

Figure 3: Output zkOracle

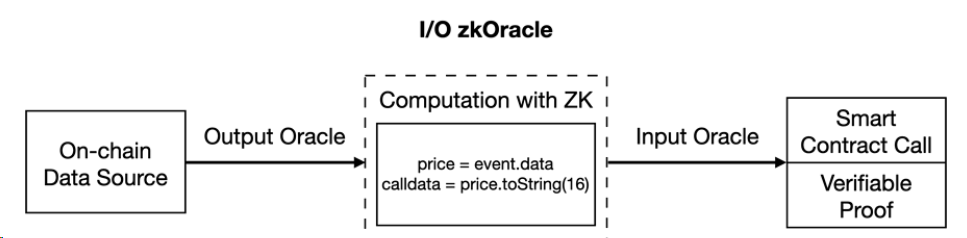

3. I/O zkOracle

Step ② - ZK Enhancement: Computation and ZK Proof Generation

The computation component of I/O zkOracle consists of both output zkOracle and input zkOracle. Compared to output zkOracle, I/O zkOracle handles more complex computations, particularly involving setting off-chain computation results as calldata for smart contract calls. This integration enables sophisticated off-chain computations to automate on-chain contract operations.

Step ③ - ZK Enhancement: ZK Proof Verification

The output of Step ② includes on-chain data (as calldata for smart contract invocation) and a verifiable ZK proof. This proof can be verified on-chain or elsewhere, ensuring computational integrity.

Figure 4: I/O zkOracle

3.3 Anonymous Voting

On-chain voting exposes all information, potentially allowing attackers to access voters' private data. Blockchain-based voting systems face two major challenges:

-

Voter identity privacy: Voters must remain anonymous during voting.

-

Verifiability of results: Mechanisms must ensure vote integrity and prevent tampering, enabling public verification of election outcomes.

Balancing voter anonymity with result verifiability in blockchain voting is a delicate challenge. ZK technology enables an effective solution to achieve both goals.

Inblockchain anonymous votingprojects, ZK technology combined with Merkle trees enables private voting and verifiable outcomes. We divide the voting process into three main phases:

1. Generating Anonymous Identities Using Hashing and Signing

Before voting, participants must verify their real identity to confirm eligibility. Upon approval, each voter receives an anonymous identity unrelated to their real identity. Using this anonymous identity protects personal information during voting.

2. Verifying Anonymous Voter Identity Using ZK and Merkle Tree

Before casting a vote, a voter must prove ownership of a valid anonymous identity.

AMerkle treestores all voters’ anonymous identities, ensuring immutability and integrity.

Identity commitments derived from anonymous identity data serve as leaf nodes in the Merkle tree. A verification circuit based on Merkle tree validates voter identity. Three pieces of data are required:

-

Current voter’s identity commitment, called input target node.

-

Root node of the Merkle tree.

-

Path index from input target node to root. Represented as binary (0 for left, 1 for right), indicating position in the tree.

During reconstruction of the root from the target node and path index, sibling nodes and user-generated commitments authenticate identity. To ensure ballot uniqueness, a hash-based identifier combining internal and external identifiers serves as voting proof.

3. Voting and Verification

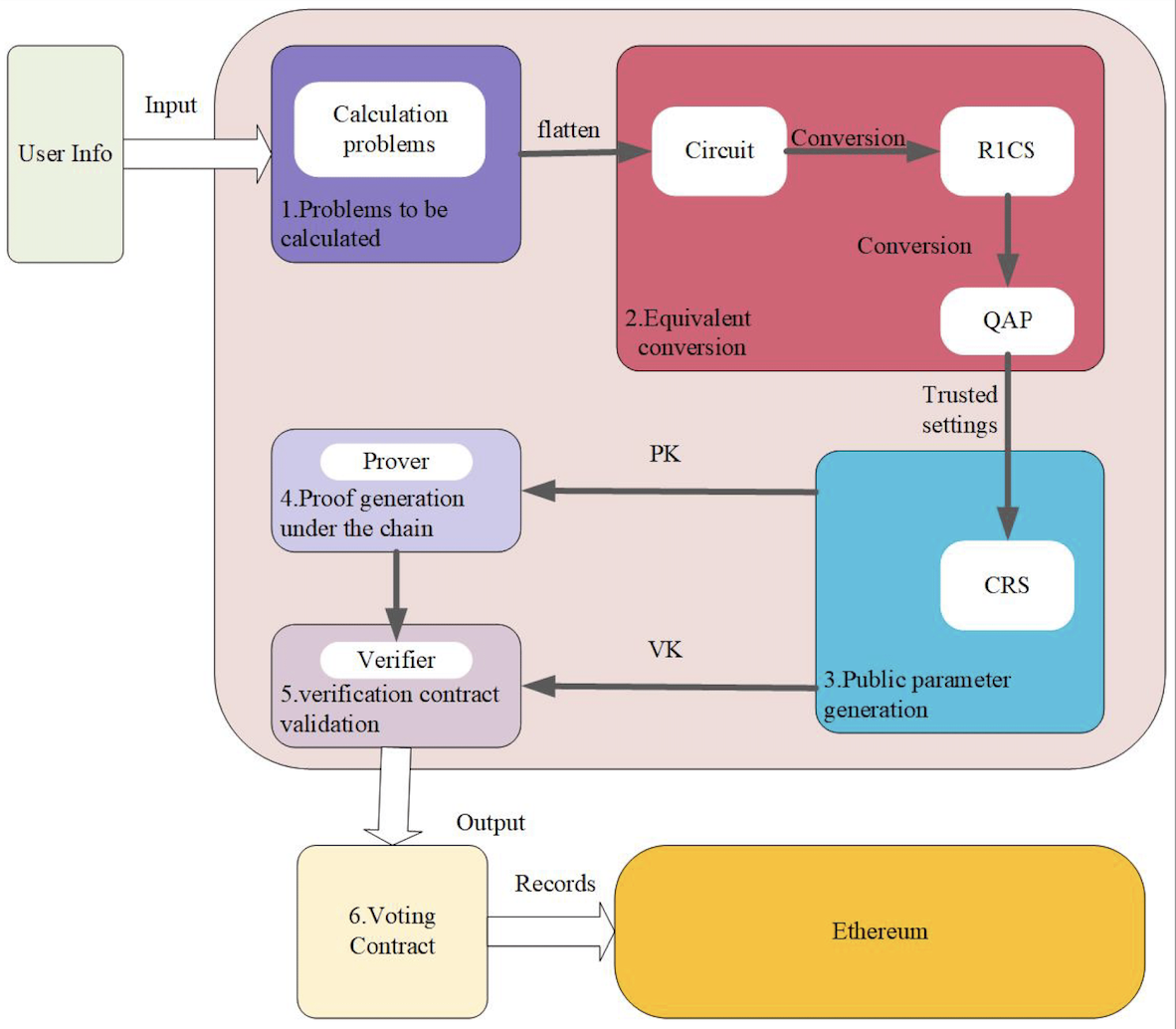

This phase consists of six steps, as shown in Figure 5:

-

Problem formulation: Insert voter’s anonymous identity into Merkle tree and prepare for verification.

-

Equivalent transformation: Convert problem sequentially into ZK low-order circuit, R1CS (rank-1 constraint system), and QAP (quadratic arithmetic program) to generate proving and verification keys.

-

Public parameter generation: A trusted setup generates common reference strings to ensure ZK system security.

-

Generate ZK proof: Use ZK circuits to generate proofs for voters. Inputs include anonymous identity and vote data—usually performed off-chain. The resulting ZK proof is uploaded to the blockchain.

-

Verify ZK proof: On-chain verification checks vote validity—i.e., whether the vote satisfies the bounded circuit system. Returns 1 if valid, 0 otherwise.

-

Voting contract: The voting contract verifies results using deployed verification contract and verification key. Throughout user-contract interaction, ZK proofs are computed via ZK circuits, effectively protecting voter identity.

Figure 5: Vote Verification Process

Based on this framework, a blockchain-based anonymous voting system can be realized.

3.4 Private Auction

Public blockchain auctions suffer from a key flaw: since all transactions are visible, anyone can observe bidders’ offers and fund balances. If a bidder learns others’ bids—or identifies their accounts—they can infer available funds from public transaction history. This allows strategic adjustment of one’s own bid based on rivals’ bids or liquidity, unfairly increasing chances of winning. Public blockchain auctions face challenges including exposed bidder identities and fund visibility. Private auctions prevent such unfair practices.

In private auctions, bidders submit offers without revealing identity or available funds. Achieving this requires overcoming two key hurdles:

-

Protect buyer identity: Bidder account identities must remain confidential, as revealing accounts exposes their available funds in the auction.

-

Protect seller interests: The auction must prevent malicious bidders from submitting bids exceeding their actual available funds.

ZK technology protects bidder identity while verifying possession of sufficient funds for the bid.

In a private auction, each bidder requires two account addresses:

-

Public staking account: Used to transfer entry fee in advance;

-

Private account: Holds the actual funds used to fulfill winning bids. If a bidder wins, funds from this account pay the final price.

These two addresses are entirely unrelated, making it impossible for others to link a bidder’s stake account activity to their highest private bid.

The private auction process proceeds as follows:

1. Verify Account Address and Available Funds Using ZK

Each bidder pre-commits the hash of their account address and available funds to a Merkle tree. ZK technology verifies that the user owns the account—i.e., the preimage (original data) of the hash matches the actual address and fund amount.

2. Validate Accounts to Prevent Artificial Price Inflation

Before accepting a new bid, the private auction contract checks the previous bidder’s account. To prevent artificial inflation, the current and previous bidders must differ. While this doesn’t fully prevent one person controlling multiple stake and private accounts, note that splitting funds reduces available liquidity per account. After staking funds into the Merkle tree, they cannot be transferred to the private account, further reducing winning probability.

3. Verify Bidder’s Available Funds Exceed Bid Amount Using ZK

Use a comparator circuit to verify that the bidder’s available funds exceed their bid, checking the following:

-

Compare available funds against bid amount. If the ZK comparator circuit returns true, the bid is valid (funds ≥ bid); otherwise invalid.

-

The circuit includes intermediate checks to prevent witness file tampering.

-

Confirm that the hash of the account address and fund amount exists in the Merkle tree.

Based on this approach, a blockchain private auction system can be implemented.

4. Conclusion

We cannot overlook the security challenges facing blockchain projects. ZK technology offers privacy protection for DeFi applications, mitigating risks like identity exposure and front-running attacks. It also enables more secure data validation for oracles. In blockchain voting, ZK supports anonymous yet verifiable elections, preserving voter privacy while ensuring result authenticity. In blockchain auctions, ZK protects bidder identity while verifying sufficient funds, safeguarding seller interests.

Yet this represents only the tip of the iceberg regarding ZK’s potential—the full capabilities of this technology remain largely untapped. In the future, we hope to see ZK applied across more blockchain projects, delivering stronger privacy and security for users.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News