The Battle for the Cross-Chain Throne: Strategies, Dominance, and Challenges

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Battle for the Cross-Chain Throne: Strategies, Dominance, and Challenges

True cross-chain means an asset is genuinely transferred to another chain (via Burn/Mint), rather than Lock/Mint or Atomic Swap.

Author: PSE Trading Analyst @Daniel Hua

Introduction

In the blockchain world, each network can be viewed as an independent ecosystem with its own native assets, communication rules, and protocols. However, this very characteristic makes blockchains isolated from one another, preventing free flow of assets and information. As a result, the concept of cross-chain interoperability has emerged.

1. Significance and Use Cases of Cross-Chain Interoperability

DeFi is today's core and foundation of blockchain technology, yet it faces numerous challenges such as fragmented liquidity, shallow asset pools, and low capital utilization. The emergence of cross-chain interoperability protocols enables consolidation of assets across multiple chains into a unified smart contract framework, thereby maximizing user experience and capital efficiency. Ideally, these protocols could reduce friction or slippage to zero.

For example:

(1) Deposit assets from the OP chain into GMX on the ARB chain to increase pool depth

(2) Use OP chain assets as collateral for borrowing and lending on Compound deployed on ARB

(3) Enable cross-chain transfer of NFT assets

Beyond finance, information transmission is equally important—such as cross-chain voting for key proposals or data exchange between social dApps. If DeFi opened the door to the cryptocurrency world, cross-chain interoperability protocols are the essential path toward success!

2. Four Types of Cross-Chain Interoperability Protocols

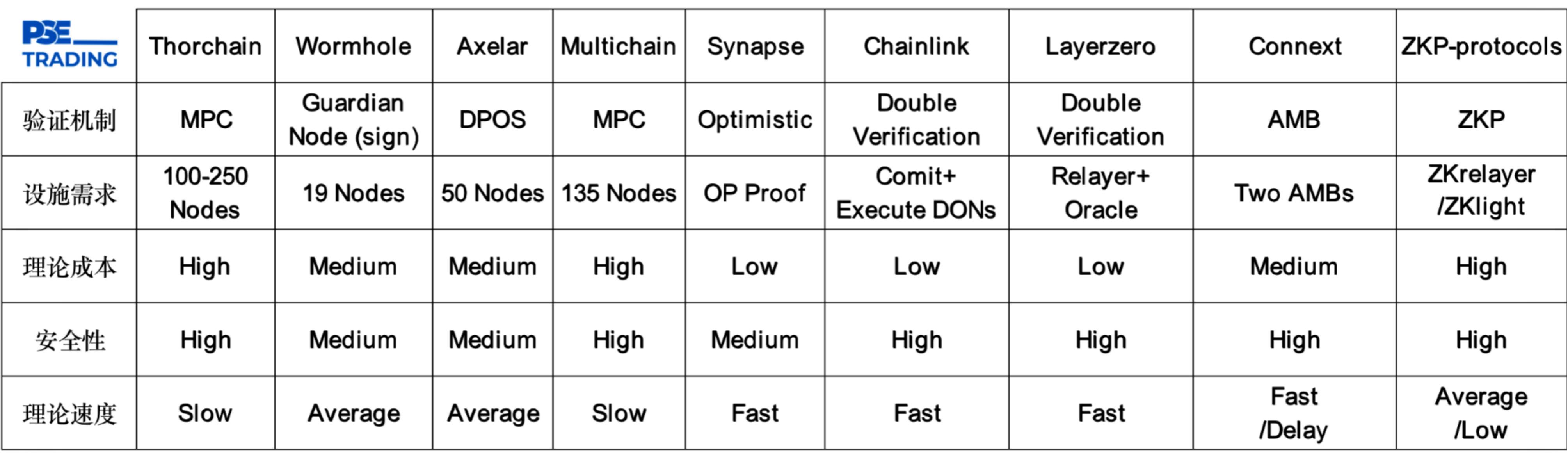

2.1 Verification Based on Nodes or Third-Party Networks (First Type)

The earliest cross-chain protocols used MPC (Multi-Party Computation) for transaction validation. Thorchain is a typical representative, employing nodes deployed on-chain to verify transactions and establish security standards. Typically, such protocols attract 100–250 node validators on the network. However, this approach has drawbacks: every node must validate each transaction, leading to long user wait times. Additionally, the operational cost of running nodes is significant for the protocol and ultimately passed on to users. Moreover, Thorchain creates a separate Liquidity Pool for each trading pair using its native token RUNE; every cross-asset transfer requires converting the source asset into RUNE before swapping into the target chain’s asset. This model demands substantial capital support and incurs slippage, making it suboptimal in the long run. Tip: Thorchain was hacked due to a code vulnerability (the system mistook fake ETH symbols for real ones), not because of flaws in its verification method.

2.1.2 Improvements

To address these issues, Wormhole selects 19 Validators to authenticate transaction validity, including well-known entities like Jump Crypto. These validators also operate validation services on other networks such as ETH and OP. Nevertheless, this approach carries high centralization risks. The author believes that full decentralization isn’t always optimal—some degree of centralized management can reduce costs. Ultimately, projects must prioritize mass adoption and maximum economic efficiency. Tip: Wormhole was attacked due to a smart contract vulnerability where attackers used external contracts to falsely validate transactions and steal funds—not related to the inherent security of its validation mechanism.

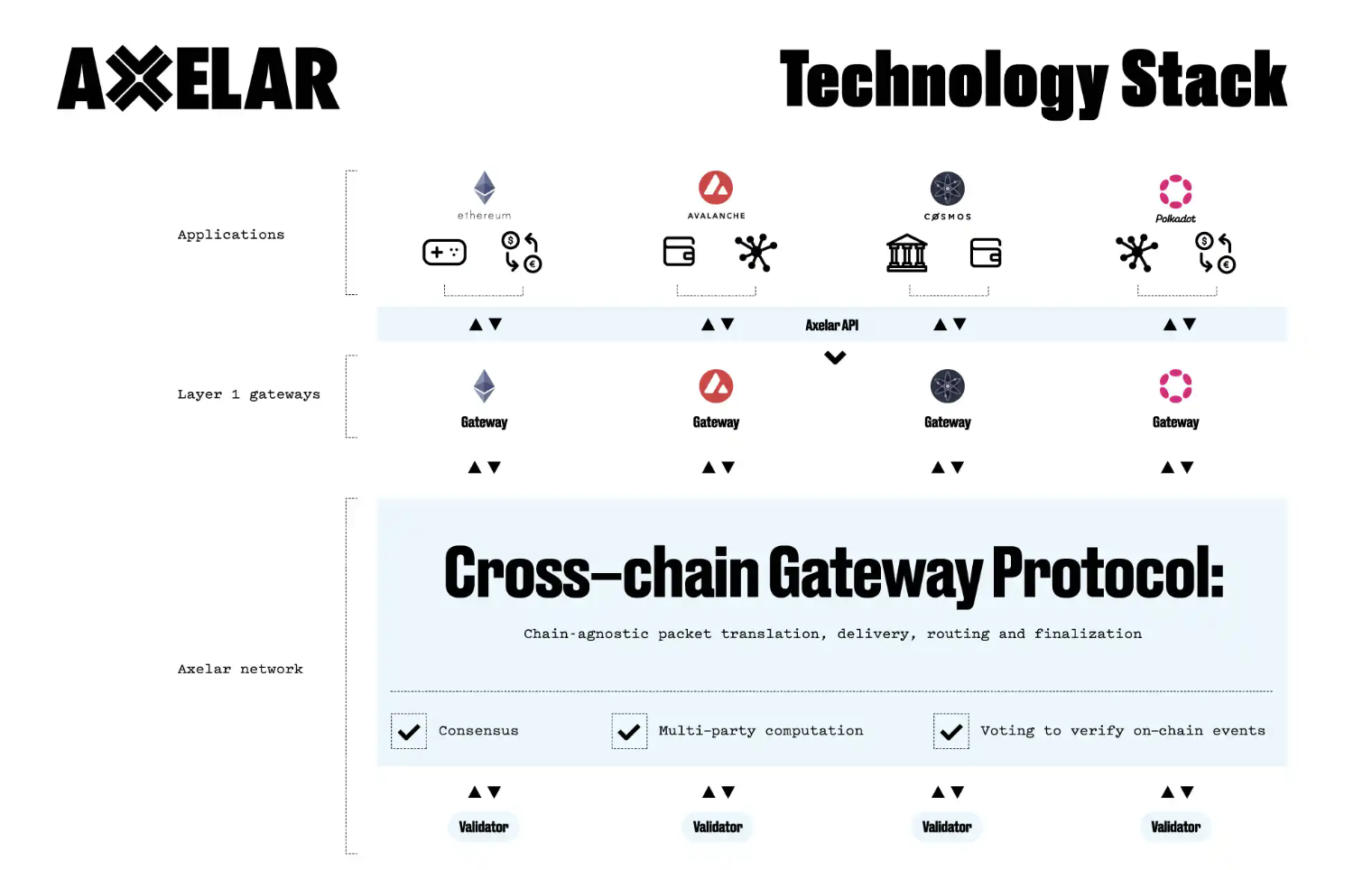

Compared to other cross-chain protocols, Axelar is a POS-based public chain. Axelar bundles verification messages from other networks and sends them to its mainnet for validation before forwarding to the destination chain. Notably, verification cost is inversely proportional to security. As the volume of verification data increases, more nodes are required to maintain network security. In theory, there's no upper limit on node count, but increasing nodes drastically raises transfer costs—a challenge Axelar may face in the future.

2.2 Optimistic Verification (Second Type)

The success of OP demonstrates the current reliability, low cost, and speed advantages of optimistic verification. Thus, cross-chain protocols like Synapse have adopted this model. However, Synapse uses a Lock/Mint mechanism to exchange assets, which poses risks of hacker attacks—the reasons will be explained in section 2.3.1. Moreover, optimistic verification only meets present needs; in the future, we’ll require even more secure and reliable methods while maintaining speed and cost efficiency. Now, the author introduces dual verification as a successor to optimistic verification.

2.3 Dual Verification (Third Type)

The most widely discussed dual verification protocols in the market are LayerZero and Chainlink. To state the conclusion upfront, the author believes dual verification holds the brightest prospects in today’s cross-chain landscape, outperforming others in security, speed, and response time.

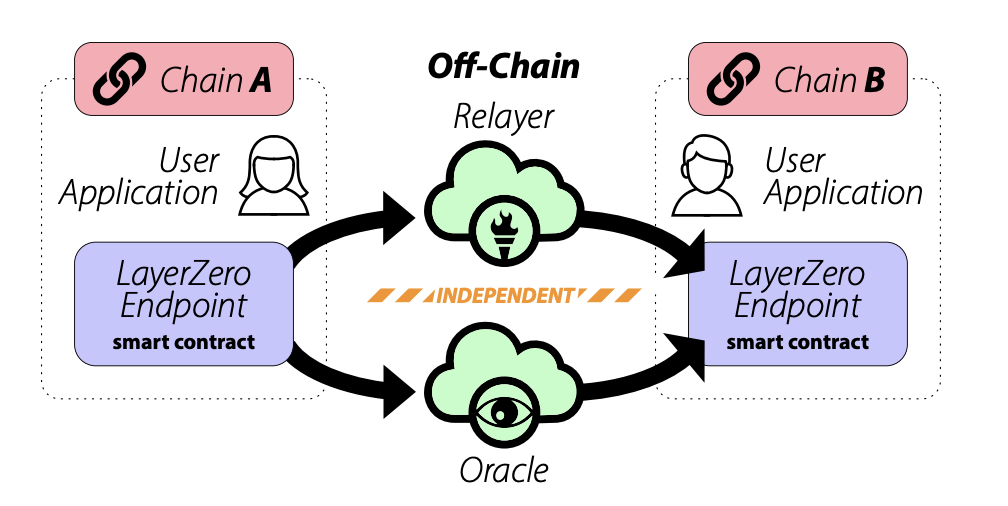

(1) LayerZero

One innovation of LayerZero is deploying ultra-light nodes across chains, transmitting data off-chain to Relayers and Oracles (provided by Chainlink) for verification. Compared to the first type, this avoids heavy computational burdens. The Oracle generates block headers and other data, while the Relayer verifies transaction authenticity. Only when both components function correctly is a transaction approved. Critically, the Relayer and Oracle operate independently. Hackers would need to compromise both simultaneously to steal assets—an extremely difficult feat. Compared to optimistic verification, this offers higher security since every single transaction is verified.

Cost and Security Advantages: The author conducted tests using Stargate (built on LayerZero technology)

1) From OP to ARB: Transaction completed in 1 minute — $1.46

2) From OP to BSC: Transaction completed in 1 minute — $0.77

3) From OP to ETH: Transaction completed in 1 minute 30 seconds — $11.42

In summary, the dual verification model holds an absolute lead.

(2) Chainlink

The Committing DON collects transaction data. On the destination chain, the ARM gathers information from the source chain’s ARM, reconstructs a Merkle tree, and compares it with the Merkle tree from the Committing DON. Once a sufficient number of nodes successfully verify the match, the transaction is submitted to the Executing DON for execution, and vice versa. Note: ARM is an independent system. The technology used by Chainlink shares ~90% similarity with LayerZero, both adopting a “collect + verify (each transaction)” model.

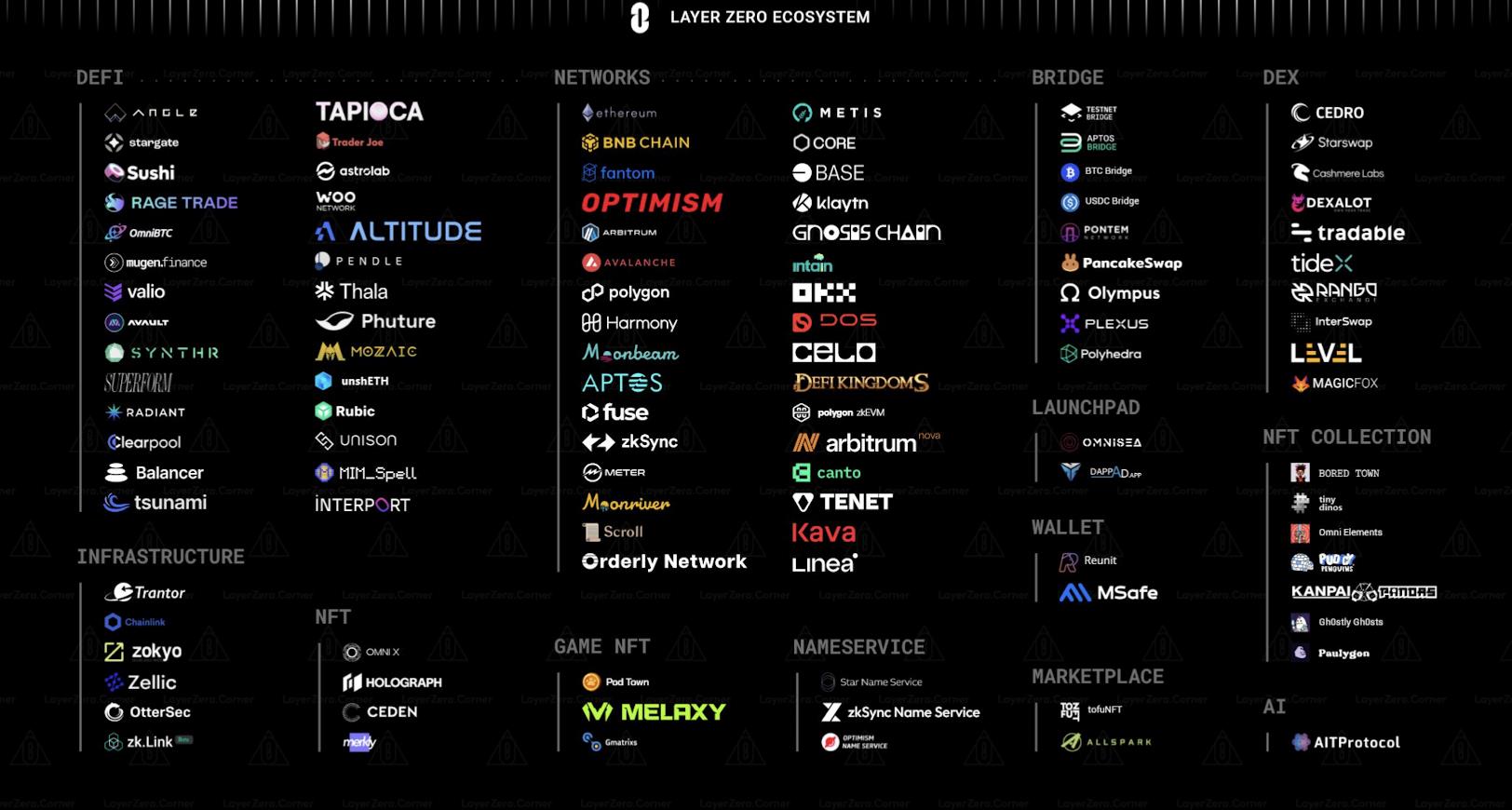

Currently, Chainlink supports projects such as Synthetix (cross-chain transfer of sUSD) and Aave (cross-chain governance voting). From a security standpoint, although ARM and Executing DON are separate systems, both are controlled by Chainlink, raising potential self-theft risks. Additionally, given similar technical foundations, Chainlink tends to attract established legacy projects seeking deep integration, creating lock-in effects. Meanwhile, LayerZero appeals more to new projects looking to deploy quickly. However, in terms of supported networks and ecosystem breadth, LayerZero currently leads. Furthermore, most project teams naturally prefer deploying their products within popular ecosystems.

2.3.1 The Impossible Triangle of LayerZero

Security: There are four models for cross-chain asset transfers:

1) Lock/Mint: The cross-chain protocol deploys liquidity pools on various chains. When a user wants to transfer ETH from chain A to chain B, the ETH on chain A is locked, and an equivalent amount of wrapped ETH (wETH) is minted on chain B. When returning from B to A, wETH is burned and the original ETH is unlocked. The risk here is that security fully depends on the bridge. If the locked value becomes large enough, hackers will inevitably target the pool.

2) Burn/Mint: Tokens are issued in OFT (Omnichain Fungible Token) format, allowing tokens to be burned on the source chain and minted on the destination chain. This avoids the attack surface created by large pooled assets and is theoretically more secure. OFT is typically chosen at token launch, facilitating circulation among dApps. Legacy projects can convert existing tokens to OFT, but doing so involves complex stakeholder coordination—for instance, how to handle native tokens already embedded in other dApps. Hence, only new projects can realistically adopt this model. Therefore, choosing security via Burn/Mint excludes compatibility with legacy projects.

3) Atomic Swap: The protocol maintains liquidity pools on both chains with balanced reserves. During a cross-chain swap, the user deposits assets into the pool on chain A, and the corresponding amount is withdrawn from chain B’s pool and sent to the user—essentially a one-to-one exchange. It is highly secure due to immediate settlement.

4) Intermediate Token: As seen in Thorchain (Section 2.1), this causes slippage and long delays.

Currently, Atomic Swap is the most widely used, but the future trend is clearly moving toward Burn/Mint, enabling truly zero-slippage cross-chain transfers while maintaining security. Another concern for legacy projects using LayerZero is oracle price manipulation—there have been many cases of oracle attacks. Since the technology is not yet mature, most protocols remain cautious.

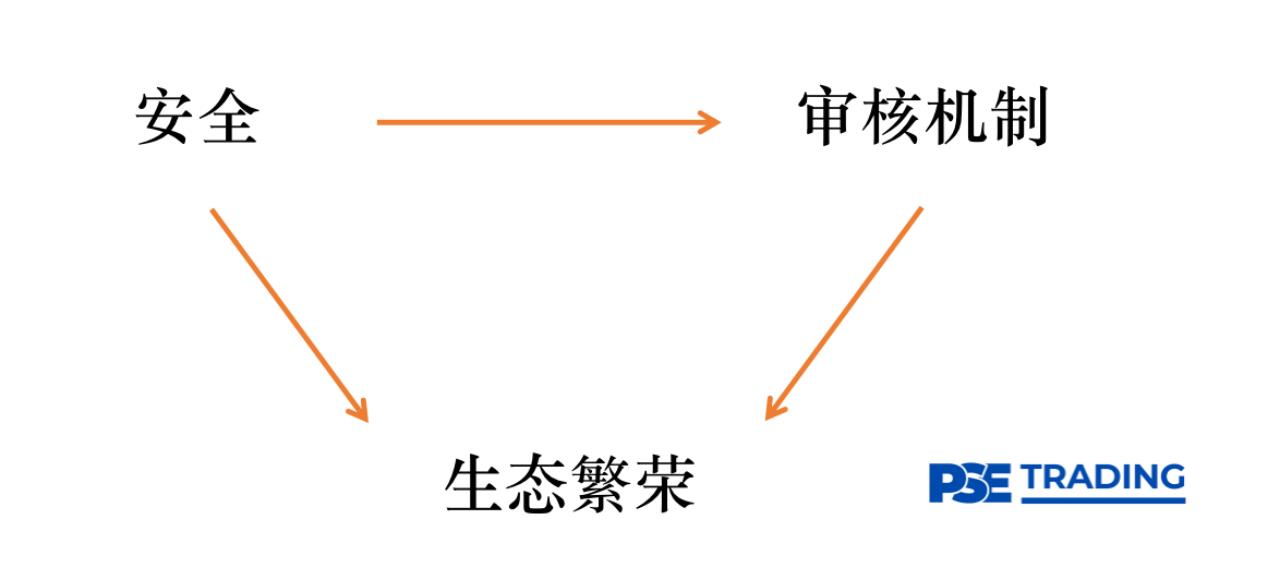

Audit: LayerZero’s Relayer and Endpoint validation parameters are set by project teams themselves, introducing risks of malicious behavior. As a result, audits are extremely strict, limiting the number of breakout projects on LayerZero. If LayerZero relaxes audits to allow legacy projects to join, security cannot be guaranteed. By prioritizing security, it becomes harder for new projects to pass audits. This creates a dilemma—LayerZero still needs time to evolve.

2.4 Modular Cross-Chain Protocol (AMB Verification, Fourth Type)

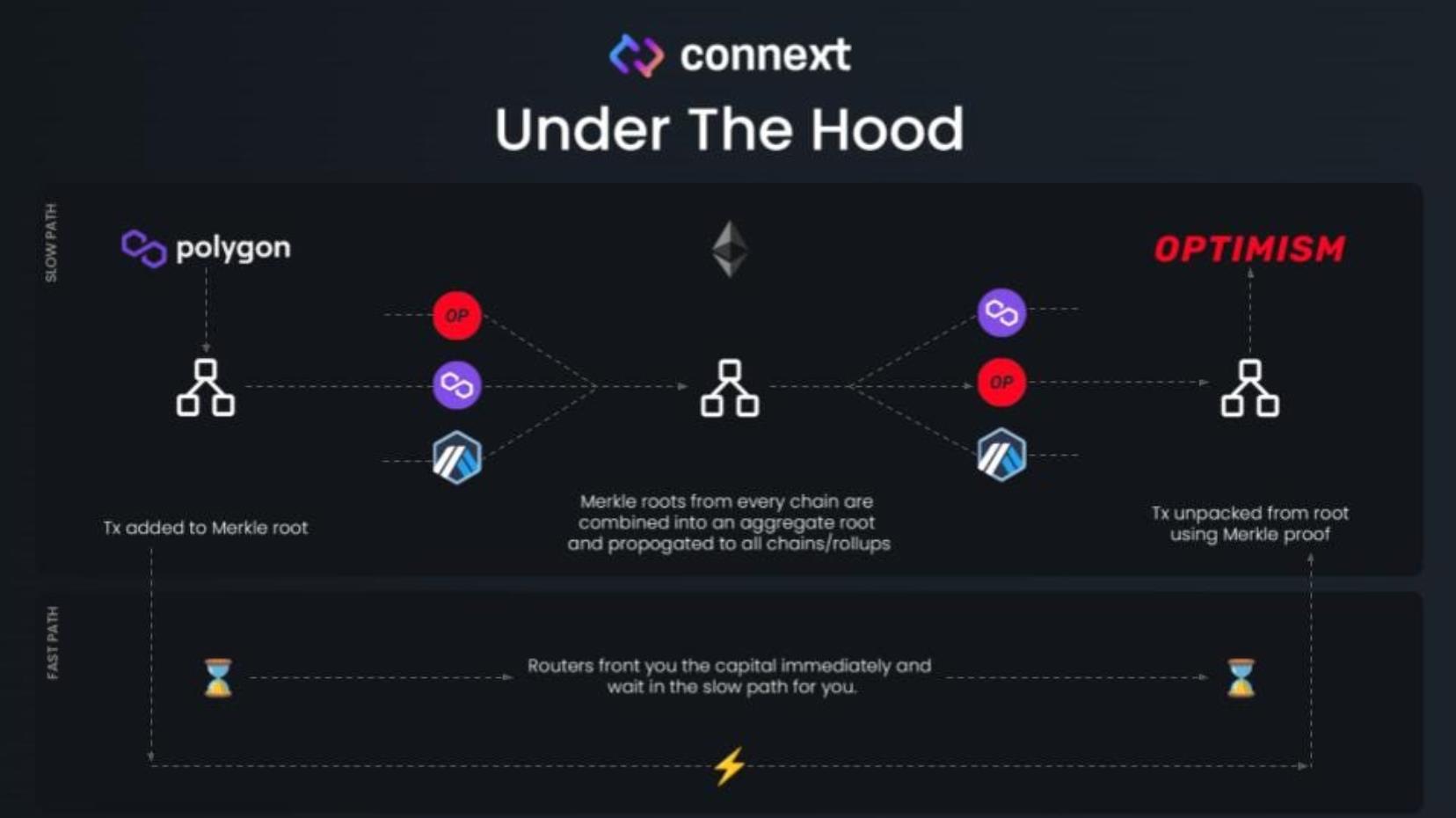

Connext is a modular cross-chain interoperability protocol with a hub-and-spoke architecture. Chains A and B perform verification via their respective AMBs (Arbitrary Message Bridges)—the spokes—while Merkle proofs generated by these AMBs are stored on the Ethereum mainnet, which acts as the hub.

This protocol offers the highest level of security because it relies on the proven security of the Ethereum network, leveraging shared security principles. In contrast, using LayerZero requires trust in the project team itself. Theoretically, this makes Connext more secure than so-called dual verification models. In the long term, some OP-based cross-chain protocols may face security concerns. The industry trend will likely shift toward ZKP or dual verification models. On the other hand, verifying native tokens across chains using individual AMB modules may result in inconsistent message delivery times. Official AMBs often require longer verification periods—sometimes up to four hours or more—which could hinder overall economic efficiency and widespread adoption, potentially limiting Connext’s scalability.

3. ZKP-Based Cross-Chain Interoperability Protocols

The current cross-chain protocol space is already highly competitive. Many teams are now turning to ZKP, aligning with the ZK rollup narrative and leveraging technologies like ZKrelayer and ZKlight-endpoint, touting superior security. However, the author believes that ZKP applications in cross-chain interoperability are premature and unlikely to compete effectively with existing solutions over the next 5–10 years, for the following reasons:

(1) Proof generation time and cost are too high. Zero-knowledge proofs come in two forms: ZK-STARK and ZK-SNARK. STARKs generate larger proofs but faster, whereas SNARKs produce smaller proofs but take longer (larger proofs mean higher costs). Most ZKP cross-chain protocols opt for ZK-SNARK to avoid excessive fees—if cross-chain costs are too high, users won’t adopt it. How do they solve the long proof time issue? Some protocols introduce a "fast lane," similar to optimistic models: approve first, verify later. But this isn't true ZKP—it’s essentially an OP Plus version.

(2) High infrastructure requirements. ZKP demands intensive computation and performance resources. Widespread adoption would strain available computing power, forcing protocols to spend heavily on infrastructure—currently uneconomical.

(3) Uncertainty around technological evolution. Among existing cross-chain protocols, dual verification already provides sufficient security for current needs. While ZKP may seem unnecessary now, future tech advancements could change that. Much like building overpasses in third-tier cities twenty years ago—short-term demand may be absent, but long-term, ZKP could become foundational to cross-chain development. Thus, while it's not yet time for ZKP, research teams should continue exploring and monitoring progress, as the pace of technological advancement is unpredictable.

4. Conclusion and Reflection

Cross-chain interoperability protocols are vital to blockchain development. Among all types, dual verification excels in security, cost, and speed, especially with industry leaders LayerZero and Chainlink. Although their underlying technologies are largely similar, LayerZero boasts a richer ecosystem, giving it a current competitive edge. However, LayerZero’s strong security and rigorous audit processes slow ecosystem growth—but more opportunities lie ahead. As for ZKP-based cross-chain solutions, while practical applications remain distant, the trajectory points in that direction, warranting sustained attention.

The author remains optimistic about LayerZero and the broader cross-chain space, but raises several concerns. Most existing cross-chain protocols belong to L0 (transport layer), primarily enabling asset transfers and information relay (social, governance, etc.). Regarding asset transfers, current bridges are pseudo-cross-chain solutions. The author argues that true cross-chain means an asset genuinely moves from one chain to another (via Burn/Mint), not through Lock/Mint or Atomic Swap. Achieving this would require dismantling all legacy systems and replacing them with new projects issuing OFT-mode tokens—a massive transition requiring extensive time and coordination.

Ultimately, we still live in a world dependent on "third parties," with blockchains remaining siloed. Regarding information transfer, chains can rely on transport layers for messaging, but current demand is limited. For example, Lens and Cyber might need cross-chain communication, but first, social dApps must achieve scale. Moreover, if most dApps deploy within the Lens ecosystem, they can communicate natively—eliminating the need for cross-chain. Cross-chain demand only becomes significant in highly competitive environments.

This leads to the emerging topic of Layer2 superchains. For instance, the success of OP Superchain may inspire more Layer2s to adopt similar architectures, enabling seamless asset interoperability. Future blockchain success may see OP and other rollups unable to handle growing user and transaction volumes, prompting even more Layer2s. Seamless connectivity here stems from sharing a common settlement layer. In this case, asset transfers bypass third parties entirely—transaction data comes from the shared settlement layer and is validated independently on each chain. Similarly, cross-chain protocols benefit most when OP, ARB, ZKsync, and Starknet coexist competitively without clear dominance, ensuring robust demand for cross-chain movement. Otherwise, if one Layer2 captures 80% of activity, cross-chain becomes redundant. Of course, much remains uncertain—the author simply shares some forward-looking considerations, subject to future developments.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News