Multicoin Capital: From UGC to UGP — Web3 Consumer Brands and Co-Creation

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Multicoin Capital: From UGC to UGP — Web3 Consumer Brands and Co-Creation

Successful Web3 consumer brands will be built together with their communities, formalizing the co-creation process and, in turn, rewarding their communities—growing together and sharing the pie.

Author: ALEKSIJA VUJICIC

Compiled by: TechFlow

Many argue that co-creation will ultimately democratize the creator class, redefine fan culture, and turn fans into creators. However, this discussion often overlooks the impact of co-creation on brands—which may be far greater than its effect on the co-creators themselves.

In the past, brands created products—and more broadly, culture—then promoted them through centralized, top-down media. Social media disrupted media distribution, naturally disrupting how culture spreads, which in turn triggered the first wave of large-scale co-creation between brands and their communities. Just as consumers could now showcase products on social media to signal participation in a particular culture, they could also shape that culture—and consequently the brands creating it—by sharing feedback, ideas, and suggestions. Thus, brands influenced consumers, who in turn influenced brands, and the cycle of co-creation began.

Yet, despite contributing value during the co-creation process, consumers received no economic return; brands captured 100% of the financial upside. In short, successful Web2 brands were built on communities but consumed the entire cake.

Successful Web3 consumer brands, however, will be built with their communities, formalizing the co-creation process and rewarding them in return—growing together and sharing the cake.

How Is Brand Culture (Co-)Created?

Starbucks is clearly much more than just a brand. It’s a “third place” lifestyle, a semi-public utility, a social “third space.” Simply put, Starbucks is a culture. But once, it was just… coffee.

When defining “how brands are born,” Marc de Swaan Arons argues that the 20th century brought standardization of high-quality products for consumers, “requiring companies to find new ways to differentiate from competitors”—thus giving birth to modern marketing. Marketers shifted focus from functional product value to building emotional connections with consumers as a point of differentiation. Brands then began aligning with subcultures and projecting those identities onto their consumers—in other words: brand culture was created top-down.

“Under the CPSE model, corporations brand products. They identify subcultures to justify the existence of products and use data-driven marketing to categorize people into demographic segments resembling starter packs. Subcultures become consumer subcultures composed of products. In the new cultural economy, culture itself becomes the product. It consists of practices, ideas, and discourses. Products are secondary, supportive, but not primary.” – Toby Shorin, Life After Lifestyle

As religious beliefs declined in the Western world, consumers began seeking meaning, identity, and belonging elsewhere—such as from influencers, or more importantly, from brands. For brands, merely associating with a subculture was no longer enough; they realized they needed to *become* the culture itself. At the same time, as the internet drove production and distribution costs toward zero, the only scarce resource became consumer attention, making community-centric marketing more valuable than ever before.

These trends have had profound implications for brands. Communities grew increasingly important, and brands could no longer create culture without consumers—making brand culture inherently co-created.

“People co-create their identities with brands just as they do with religion, community, and other meaning systems. This constructivist view is incompatible with popular forms of postmodern critique, yet it opens up new critical possibilities. We live in an era where brands don’t just reflect our values—they must act upon them. Trust in businesses is no longer based on visual signals of authenticity, but solely on demonstrated action.” – Toby Shorin, Life After Lifestyle

From User-Generated Content (UGC)

Culture has always been transmitted through content. When information was broadcast via top-down media like radio, television, and newspapers, culture spread in a top-down manner. The rise of social media changed that. On platforms like Instagram and TikTok, content creation became democratized and decentralized—and so did culture. As brands recognized the need to co-create culture with their communities, they turned to social media and UGC to achieve it.

Rather than simply encouraging consumers to post photos wearing their branded apparel, brands began soliciting immediate feedback, ideas, requests, and more directly from their communities. In response, communities started shifting from co-creating content to co-creating products.

Glossier defined the direct-to-consumer (DTC) era using exactly this approach—their decision to use pumps instead of jars, and to launch mineral-based sunscreen, came directly from input in their Slack community. Since then, community co-creation has become a standard practice in modern marketing handbooks, adopted across industries by brands such as Samsung, Supergoop, Chipotle, IKEA, LEGO, Unilever, and many others—indeed, there’s even a book dedicated entirely to this topic.

Yet a crucial question remains unanswered: What did the inventor of the Hazelnut Macchiato receive after submitting their idea to Starbucks?

Moving Toward User-Generated Products (UGP)

Co-creation faces an attribution problem—and Web3 solves it.

Borrowing an idea from Marty Bell, founder of Vacation and Poolsuite, future brands will resemble “open companies,” where brands build the products their communities want, together. He said:

“For years, I thought the right way to build brands and businesses was to hide away, work quietly, and then launch a finished product saying, ‘Here’s our new thing…’ What I hope NFTs will enable going forward is involving people in the creative process and building with them. I believe all of this should be open, not done behind closed doors. Right now, we might have 20 ideas about what to do next. We’re equally excited by all of them—it doesn’t matter to us. What matters most is what excites our community the most.”

Web3 enables co-creation—and thus the future “open company”—through two key mechanisms: improved human coordination and better attribution.

-

Human Coordination: In any heterogeneous organization (which describes much of Web3), communities face challenges around making collective decisions—especially in co-creation, which requires precise and effective human coordination. Tokens serve as a powerful coordination tool, enabling brands to verify membership, authenticate credentials, grant permissions, and enable voting mechanisms.

-

Attribution: As discussed throughout this article, brands already engage in co-creation with consumers—the issue lies in the lack of social and financial recognition for these contributors. Yet, as Sari Azout wrote in her piece *Attribution +*:

“The real power of Web3 technology lies in reshaping how value is created, shared, and distributed on the internet, making distributing value as easy as sending and receiving email. This is a foundational technical unlock that allows internet creators to capture more of the value they generate.”

Tokens allow brands not only to attribute social credit by recording provenance and origin points of creativity but also to pass financial value directly to those who contributed the ideas.

We see entrepreneurs, developers, and brand builders leveraging new collaborative strategies to build a new class of brands that increase engagement, sales, loyalty, and retention—while aligning their value with that of their communities. Co-creation falls into three main categories: individual creation, group creation, and community creation.

1. Individual Creation: In the future, brands will release blank-canvas digital products (mutable NFTs) as “templates” designed for consumers to remix according to their tastes. Imagine a blank Porsche car or Air Jordan shoe that consumers can fully customize based on their unique vision.

Each consumer will own a uniquely designed digital item and have the option to produce a 1:1 physical version. Additionally, the community may vote on a collection of designs to select one for mass-market release.

Strong examples include Nike x RTFKT’s “Your Force One” project, where CloneX holders could design their own Air Force 1, with a chance to see it produced in real life. Similarly, Porsche’s latest NFT allows holders to design their dream car, with the community voting on favorites, culminating in seeing that car speed down the highway.

2. Group Creation: A group can consist of any set of individuals—ideally between 5 and 50 people—with a shared goal of producing one product or a limited series. This echoes Yancey Strickler’s concept of MetaLabel, which he defines as “a group of people using a shared identity to pursue a common goal, focused on public releases that express their worldview.” In this case, a cohort collaborates with a brand on product development.

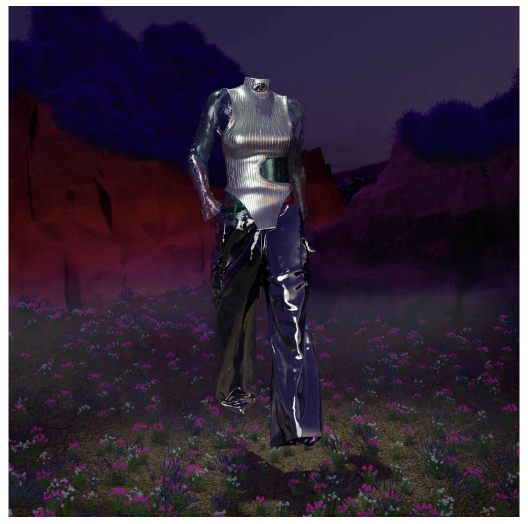

Digital fashion co-creation platform Effekt recently launched its first group creation project, paving the way forward. Twenty members from its global community gathered in a Discord chat to help co-create the brand’s first in-house fashion item. Over several weeks, the cohort collaborated on mood boards and inspiration, submitted design suggestions, and advanced the design process through voting, written proposals, image submissions, and other feedback systems. While the queue provided all input and feedback, the final product was produced by Effekt, allowing them to engage the community while retaining some control over the outcome. The resulting digital fashion item will be sold as a limited-edition NFT, with revenue shared between Effekt and the co-creators.

Moving from real-world cases to hypothetical ones, we can imagine a brand like Rebecca Minkoff recruiting a small cohort of around 20 consumers to co-create a capsule collection. Members might be selected based on prior credentials—such as holding an Access NFT, purchase history, winning a design contest, etc. Once chosen, members could gather in a private chat to provide design input, fabric feedback, and vote on outcomes, possibly mediated via governance tools like JokeDAO. Access NFTs could embed smart contracts enabling revenue-sharing from product sales, or each team member could receive a portion of the collection via digital marketplaces like DressX. The surface area for collaboration here is vast.

3. Community Creation: An even broader possibility involves a brand emerging entirely from a tokenized community, collectively deciding what kind of product they want to see—akin to CPG Club or Poolsuite. While decentralized ideation has advantages, we believe execution still requires a degree of centralization, led by capable teams who turn ideas into reality. With built-in mass distribution and engaged consumers playing an active role, this could be the magical formula for launching the next wave of successful consumer brands.

Conclusion

As the volume of co-created products grows, we expect builders to leverage blockchain—through both fungible and non-fungible tokens—to establish social and financial alignment with their communities.

On-chain co-creation will give rise to better products, stronger communities, and a beautiful flywheel of consumer capitalism. To incentivize this behavior, brands must first recognize and reward it—Web3 makes this possible through membership, provenance, reputation, revenue sharing, and more.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News