A Ten-Thousand-Word In-Depth Analysis of Cross-Chain in the Multi-Chain Landscape

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

A Ten-Thousand-Word In-Depth Analysis of Cross-Chain in the Multi-Chain Landscape

Let's look forward to the endless possibilities of blockchain together!

Author: @jesse_meta

This article is an entry for the DiFieye×celer writing competition.

I. A Multi-Chain Future with One Dominant Chain and Several Strong Competitors

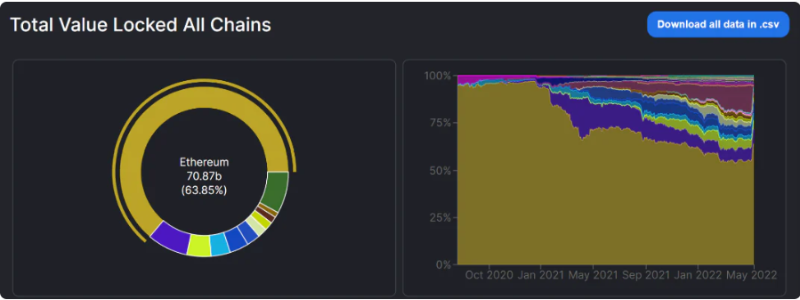

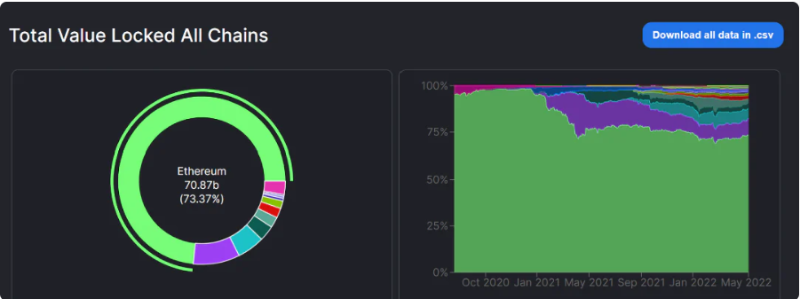

In early 2020, Ethereum's fees were still friendly for most DeFi users. However, as the Ethereum ecosystem rapidly expanded during the "DeFi Summer," the surge in Total Value Locked (TVL) and new users led to skyrocketing gas fees for contract interactions, deterring smaller investors. Ethereum’s limited transactions per second and block production speed also constrained interaction efficiency. This prompted investors and developers to seek cheaper and faster alternatives to absorb value overflow from Ethereum. As shown in Figure 1, we can clearly see that Ethereum’s share of total market TVL has been steadily declining (excluding the impact of Terra’s collapse in mid-May).

Figure 1: TVL Across All Public Blockchains. Data source: DefiLlama

According to Blockchain-Comparison.com, by May 14, 2022, there were already 115 Layer 1 public blockchains on the market. For some users, low transaction fees are the top priority, while decentralization may not be crucial. This creates opportunities for EVM-compatible Layer 1 chains. Based on DefiLlama data, BSC, Avalanche, and Fantom rank among the leading EVM chains, locking up significant capital. In the EVM chain market, non-Ethereum EVM Layer 1 chains captured about 25% of Ethereum’s market share between January and May 2021. However, as Figure 2 shows, Ethereum’s market share has remained stable at around 75% since May 2021, maintaining its dominant position.

Figure 2: Comparison of Ethereum TVL vs. EVM Layer 1 TVL. Data source: DefiLlama

According to DefiLlama, the ratio of Non-EVM Layer 1 TVL / (Ethereum TVL + Non-EVM Layer 1 TVL) increased from 24% in February 2022 to 30% on May 3, 2022 (due to the collapse of Terra’s algorithmic stablecoin, this ratio dropped to 16.8% based on data from May 14). Chains like Solana and Near have seen significant TVL growth under strong capital support, attracting many new external users and existing Ethereum users unable to afford high fees due to their low gas costs.

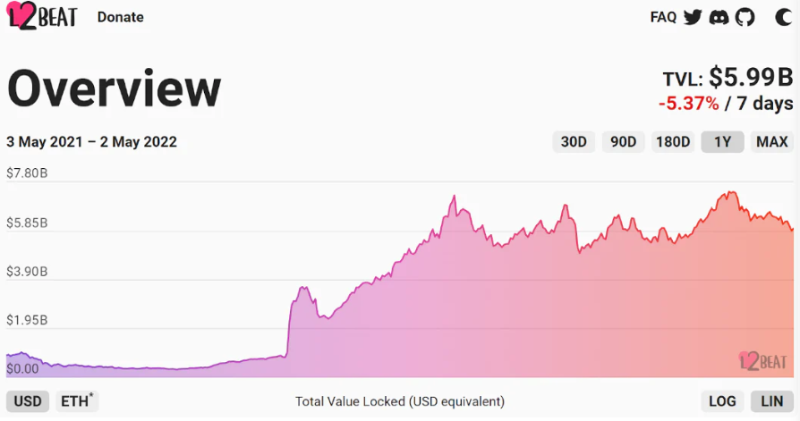

According to L2Beat, Layer 2 TVL grew from $890 million on May 3, 2021, to $5.99 billion on May 2, 2022—an increase of 6.7x. During the same period, Ethereum’s TVL only rose from $90 billion to $110 billion. With incentive programs such as Optimism’s token distribution and continuous improvements in ecosystems like Arbitrum, Zksync, and StarkNet, Layer 2 TVL is expected to keep growing.

Figure 3: Layer 2 TVL. Data source: L2Beat

The above data indicate that due to Ethereum’s persistent issues with high gas fees and slow speeds, various Layer 1 and Layer 2 solutions have benefited from value spillover. Ethereum’s biggest moat remains its $110 billion TVL, anchored by major native lending platforms and deep liquidity pools—positions unlikely to be shaken soon. Ethereum will continue to attract top developers and remain the largest public blockchain for the foreseeable future, serving as the settlement and consensus layer for the blockchain world. Other blockchains will seize this opportunity to develop into specialized application-specific chains based on their unique mechanisms, capturing niche market shares. For example, Terra and Kava focus on finance, Avalanche and WAX target gaming, Flow and Immutable specialize in NFTs, while Aztec and Oasis offer privacy solutions. The massive demand for the metaverse provides ample room for growth, paving the way for a diverse, multi-chain future.

II. Cross-Chain Needs and Concepts in a Multi-Chain Landscape

Major public blockchains, benefiting from high valuation ceilings, have attracted investments from numerous institutions and experienced rapid ecosystem development over the past year. However, due to technical and competitive reasons, most blockchains cannot directly interoperate, causing users, assets, data, and dApps to remain isolated within their respective ecosystems—like standalone computers—creating a “silos” effect, which contradicts the core principles of blockchain interoperability and scalability.

Under these conditions, cross-chain needs among blockchain natives begin to emerge, prompting exploration into the feasibility of blockchain interoperability.

Cross-Chain vs. Cross-Layer

We must first clarify the definitions and differences between cross-chain and cross-layer.

Cross-chain refers to transferring messages between different blockchains. Different chains maintain separate ledgers and accounting units. Sidechains do not report their records back to the mainchain, only communicating when a cross-chain event occurs.

Cross-layer refers to information transfer between Layer 1 and Layer 2. It involves changes within the same ledger system. Layer 2 shares the same accounting unit as its Layer 1, and its records are periodically reported to the mainchain.

In practice, however, many users overlook this distinction and classify cross-layer operations under the broader category of cross-chain.

Classification of Cross-Chain Behaviors

User cross-chain behaviors can be divided into narrow and broad categories. Narrow cross-chain behavior refers to token bridging (token swapping, token transfers), while broad cross-chain behavior encompasses message passing across chains.

Narrow Cross-Chain Behavior

- Token Swapping

Each public blockchain has its native token as a value carrier, allowing users to swap tokens within the chain. Before cross-chain bridges existed, users could only perform cross-chain token swaps via centralized exchanges. For instance, if Alice wanted to exchange BTC for ETH, she would deposit BTC into a centralized exchange, convert it to ETH, and then withdraw it onto the Ethereum chain.

With the advent of hash time-lock contracts enabling atomic swaps, Alice can now conduct decentralized token swaps directly on-chain, exchanging BTC for ETH. Inter-chain token swapping is a critical prerequisite for realizing the “Internet of Value.”

- Token Transfer

Blockchains are inherently closed systems; native assets on one chain cannot be directly transferred to another. Using cross-chain bridge technology, users lock native assets on the source chain and mint equivalent wrapped assets on the destination chain, achieving token transfer. A classic example is Wrapped BTC (wBTC) on Ethereum.

Both token swapping and token transfer solve the problem of value isolation between chains. Additionally, token transfer enhances DeFi openness. For example, wrapped BTC can be used in DeFi applications on other chains, DAI can be moved to Venus—a faster, cheaper, higher-yielding platform—for yield farming, or ETH can be transferred to Oasis to pursue transaction privacy.

Broad Cross-Chain Behavior

Message Passing Across Chains

Here, “messages” refer to any complex cross-chain requests made by users.

The essence of cross-chain behavior is a combination of message transmissions. Through cross-chain messaging, Chain A can read Chain B’s state and information, using them as triggers for execution. For example, token transfer is completed through two cross-chain messages: first locking funds on Chain A and sending confirmation to Chain B, then Chain B verifies the authenticity and mints the corresponding wrapped token, finally feeding back the status to Chain A.

Through cross-chain message transmission, chains become interconnected instead of isolated. One chain can read and verify the information and states of another, enabling advanced functionalities such as cross-chain lending, cross-chain NFTs, cross-chain aggregators, cross-chain governance, and cross-chain derivatives—making the vision of blockchain as an Internet of Value truly possible.

III. Key Cross-Chain Messaging Protocols

In the previous section, we learned that the essence of cross-chain behavior lies in inter-chain message transmission. Now, let’s examine how several important cross-chain messaging protocols currently available in the market achieve this.

The Inter-Blockchain Communication Protocol (IBC)

If we consider Ethereum as a supercomputer, Cosmos is the internet connecting independent servers—essentially a blockchain internet. Cosmos itself is not a blockchain but rather a foundational protocol for designing application-specific blockchains (called Zones).

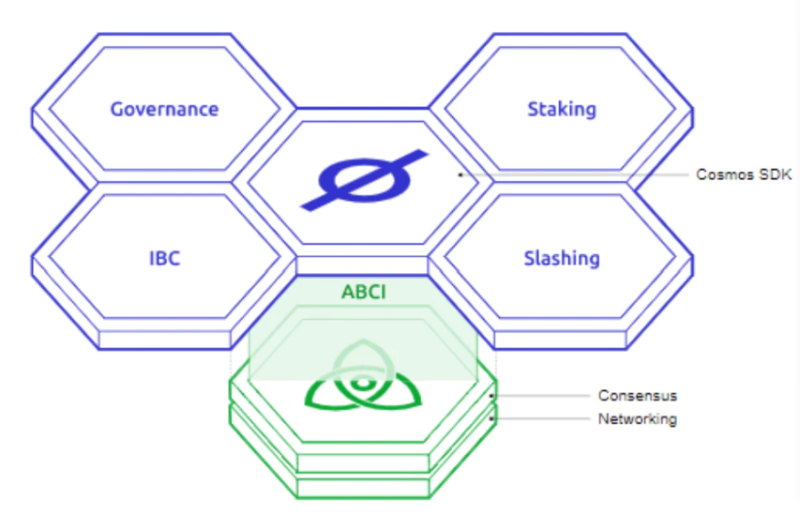

Cosmos consists of three core components: the Tendermint consensus engine, the Cosmos SDK, and the Inter-Blockchain Communication (IBC) protocol.

The Cosmos SDK (Software Development Kit) offers basic blockchain modules such as staking, governance, and token distribution, reducing redundant development efforts and allowing developers to focus on building application-specific chains.

Figure 4: Cosmos SDK Modules

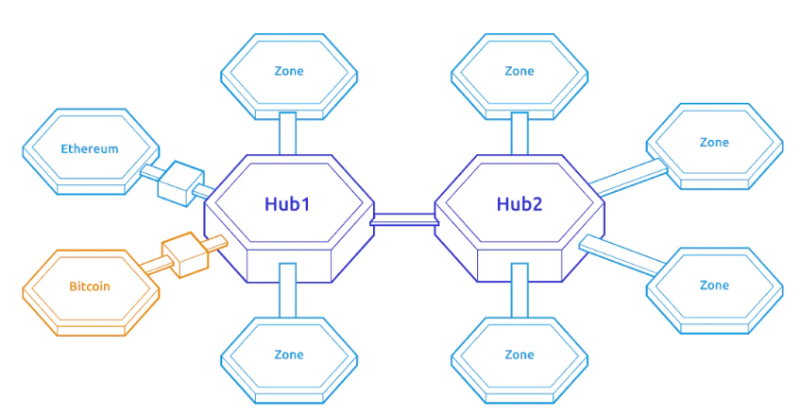

As shown above, IBC is actually a key module within the SDK. Chains within the Cosmos ecosystem can use IBC for reliable, ordered token transfers, cross-chain data availability proofs, shared security, and other forms of interoperability. As illustrated in Figure 5, communication between Hub1 and Hub2, or between Hubs and application-specific Zones, occurs via the IBC protocol.

Figure 5: Structure of Cosmos Hub and Zones

It should be noted that only blockchains with fast finality (transactions quickly confirmed and irreversible) are compatible with IBC. Proof-of-Work chains like Bitcoin and Ethereum are not suitable for IBC communication. These types of blockchains interact with Cosmos through Peg-Zones. Due to space limitations, we won’t elaborate further here.

How does IBC work specifically? Communicating blockchains run lightweight clients to receive each other’s block headers and track validator sets. When Chain A wants to transfer tokens to Chain B, it must first stake the tokens on Chain A and send proof to Chain B. Chain B verifies the proof using Chain A’s block header, locks the original tokens on Chain A, and mints corresponding wrapped tokens on Chain B. When returning tokens to Chain A, a similar mechanism unlocks them.

LayerZero

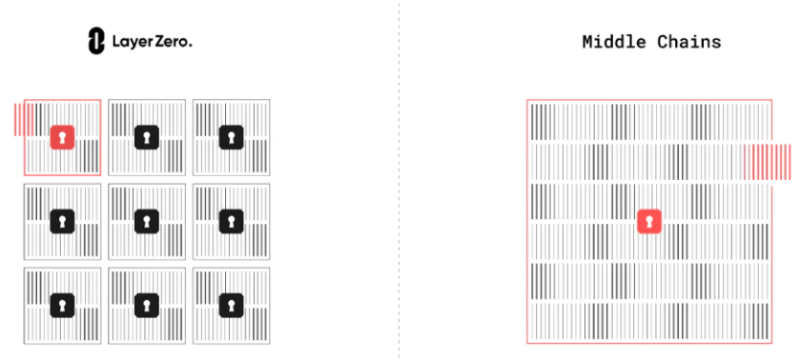

LayerZero aims to address the shortcomings of intermediary chains and IBC by enabling communication between every smart contract across all chains.

Intermediary chains hold signature authorizations for all inter-chain messages, making them vulnerable to single-point attacks given enough time. Although they offer lower cross-chain fees, they compromise on security.

Using Cosmos IBC’s transport layer to connect Ethereum and other EVM-based blockchains is safer than intermediary chains but comes at a higher cost, limiting IBC’s adoption. Moreover, as previously mentioned, IBC only allows direct communication between blockchains with fast finality.

LayerZero is a message transport layer enabling smart contracts to communicate across blockchains. It uses oracles and relayers to facilitate asset transfers and ensure security, seamlessly supporting both deterministic and probabilistic transactions, offering applications a community-driven, cheaper, and faster omnichain communication standard.

So, how does LayerZero achieve this vision?

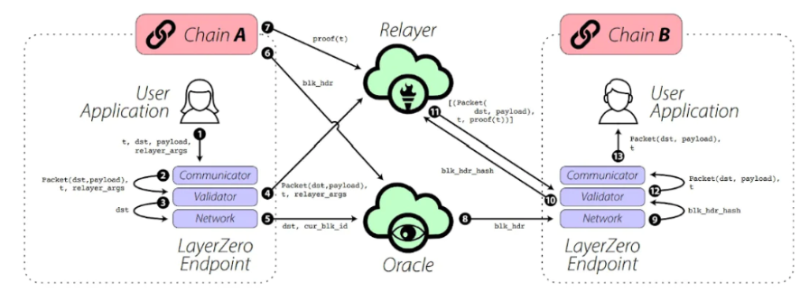

LayerZero introduces ultra-light nodes (ULNs), applying the same verification method as on-chain light nodes (ensuring security), but instead of storing all block headers sequentially, it streams block headers on-demand via decentralized oracles—reducing costs while maintaining security. LayerZero acts as a user-configurable endpoint deployed on each chain (akin to a broadcast station in every village). It relies on independent oracles and relayers for message transmission.

When a user application sends a message from Chain A to Chain B, the message originates from the endpoint (LayerZero) on Chain A, notifying the user’s oracle (partial info) and relayer (full info). The oracle forwards the block header to the LayerZero endpoint on Chain B, and the relayer subsequently submits the transaction proof. Once verified on Chain B, the message is delivered to the destination address.

Figure 6: LayerZero Message Transmission Process

By combining existing oracles with an independent relayer system, LayerZero increases security (since the relayer enables Chain B to re-validate events on Chain A). Compromising Chainlink’s DON is difficult. Even if the oracle is breached, the relayer provides backup validation. At worst, only users relying on compromised oracle A and relayer A face risks—the rest remain unaffected (unlike intermediary chains, where a single breach collapses the entire system). Applications can choose trusted oracles or even run their own relayers. Currently, Chainlink is the default oracle.

Figure 7: LazyZero’s Multi-Point Configuration vs. Single-Point Configuration of Intermediary Chains

Celer Cross-Chain Message Framework

Launched in late April, Celer’s Cross-Chain Message framework (Celer IM) is a developer-oriented infrastructure and SDK for building cross-chain applications. Celer IM SDK is plug-and-play and developer-friendly. Existing multi-chain standalone apps can become natively cross-chain by integrating a simple contract plugin. All apps integrated with Celer IM allow users to stay on one chain and perform one-click cross-chain operations without switching networks.

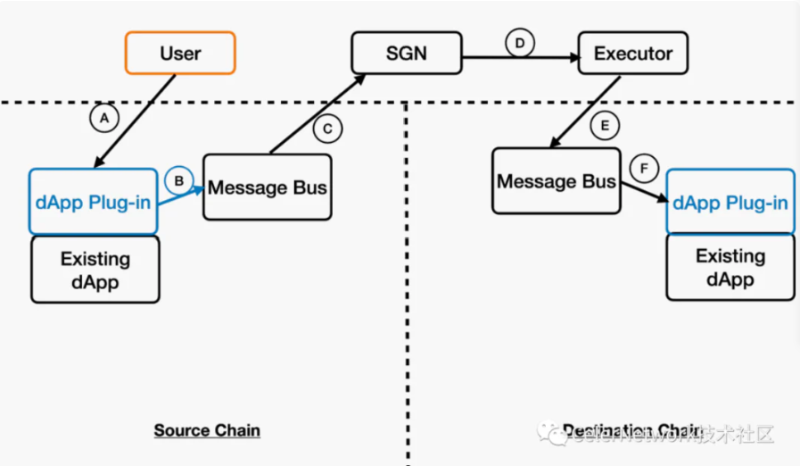

Celer IM’s architecture mainly consists of two parts: on-chain Message Bus smart contracts acting as “mailboxes,” and the State Guardian Network (SGN)—the “messenger” linking chains and transmitting messages. SGN itself is a PoS chain built on Cosmos Tendermint, requiring nodes to stake CELR tokens to participate in consensus.

In Celer IM, users no longer interact directly with existing dApp smart contracts. Instead, they engage with a new dApp Plug-in contract (marked A in Figure 8), expressing desired cross-chain logic. This is typically the only transaction a user makes to initiate cross-chain interaction. The dApp Plug-in becomes part of the overall business logic, interacting with the dApp’s existing smart contracts on the source chain. The Plug-in sends the user’s cross-chain request as a message to the “outbox” Message Bus smart contract on the source chain. This “outbox” is monitored by SGN, whose validating nodes reach consensus on the message’s existence and generate a weighted multisig proof. This proof is stored on the SGN chain until an Executor relays it to the target chain’s Message Bus (“inbox”). The inbox contract validates the message and delivers it to the recipient dApp contract on the target chain, triggering corresponding actions.

Figure 8: Celer IM Message Transmission Process

Celer IM’s security relies on SGN. The security model resembles that of other Tendermint-based L1 blockchains like Cosmos and Polygon: malicious nodes are penalized and slashed through battle-tested consensus mechanisms, incurring substantial financial loss. This is safer than other multisig solutions like LayerZero, which lack economic penalties for bad actors. Celer IM leverages SGN’s lightweight yet robust security model, ensuring fast performance, backed by a consensus algorithm already securing billions in assets across other blockchains.

What if a majority of staked nodes turn malicious? While unlikely, Celer IM includes a secondary safety layer inspired by Optimistic Rollups to guard against black swan events. Every cross-chain message undergoes a mandatory “quarantine period.” When a message reaches the target chain via SGN, it isn’t immediately executed but held temporarily. During this window, app developers and SGN node operators can verify the message on the source chain. This trade-off of latency for enhanced trust-minimization ensures system-wide security—as long as at least one honest participant exists among all SGN and monitoring nodes. In practice, Celer’s cBridge employs both models: small transfers rely on immediate SGN execution, while large transfers go through enforced quarantine periods. We’ll explore cBridge’s technical details later.

From the above, we understand that LayerZero is purely a message-passing layer moving data from Chain A to Chain B. In contrast, Celer IM features intelligent message routing—messages pass through SGN, which performs computations and transformations based on real-time data from multiple chains before executing more complex operations on the target chain. For example, ChainHop, a cross-chain DEX built on Celer IM, runs its price calculation entirely on SGN. Since SGN has direct access to real-time liquidity across chains, it can monitor and adjust pricing dynamically, enabling more powerful applications than simple message relaying.

These are three key cross-chain messaging protocols. Earlier, we stated that cross-chain behavior fundamentally consists of message transmission sequences. Next, let’s discuss how token bridging—the most common cross-chain activity—is implemented.

IV. Token Bridging Solutions

- Centralized Exchanges: The safest cross-chain solution, eliminating post-transfer concerns. However, drawbacks include centralization, exposed user privacy, limited supported chains, and cumbersome processes. (DeFieye’s deposit/withdrawal dashboard displays real-time withdrawal fees across major CEXs: https://tools.defieye.io/transferfee)

- Official Bridges, such as Avalanche’s Avalanche-Ethereum Bridge (AEB), Solana’s Wormhole, NEAR’s Rainbow Bridge. These bridges offer relatively high security under dedicated mechanisms but come with higher fees and less convenience. For example, withdrawing assets from Arbitrum back to Ethereum via the official bridge requires a seven-day waiting period.

- Specialized Asset Bridges: Designed to bring native tokens from blockchains without smart contract capabilities (e.g., BTC, Dogecoin, Zcash) onto smart-contract-enabled chains for DeFi use. Protocols in this space include BitGo, Ren Protocol, Keep Network—but they carry risks of centralized control.

- Third-Party Bridges: Dedicated solely to token bridging, offering low fees, fast speeds, and wide token support. However, security levels vary significantly. Projects include Celer Network, Hop Protocol, Multichain, Synapse Protocol, etc.

- Bridge Aggregators: Aggregate major cross-chain bridges and recommend optimal routes based on user needs. (DeFieye’s bridge tool helps users find the lowest-cost option across mainstream bridges: https://tools.defieye.io/bridge/)

Types of Third-Party Bridges

Third-party bridges represent the most capital-attractive and widely used segment in token bridging. Let’s examine the main types.

Hash Time-Lock Atomic Swaps

HTLC is a cryptographic method enabling atomic transactions. The process works as follows:

1. User A generates a random secret r, computes its hash m = hash(r), and sends m to User B.

Simultaneously, User A initiates a transaction sending 1 BTC to User B, which succeeds only if User B reveals r within a preset timeframe; otherwise, it fails automatically.

2. Upon seeing A’s transaction, User B sends 10 ETH to User A, conditioned on User A revealing r within the deadline; otherwise, the transaction also fails.

Note: Hash functions are irreversible—knowing m doesn’t reveal r. But knowing m allows creating a transaction requiring r as proof. After A reveals r, the contract checks whether hash(r) matches m, verifying authenticity.

3. Seeing B’s transaction, User A reveals r, claiming the 10 ETH, thereby disclosing r.

4. With r now known, User B claims the 1 BTC from A’s transaction.

Thus, two transactions across separate chains are unified into a single atomic event—either both succeed or both fail. This is considered the safest and most trustless form of token transfer.

However, this approach has four drawbacks:

- Requires finding a peer counterparty, resulting in potential delays and low efficiency.

- Counterparties can selectively complete trades based on favorable exchange rates, making it unsuitable for large transactions.

- Complex underlying mechanics lead to higher fees.

- Supports only token swaps, not token transfers.

cBridge 1.0 used this method.

Liquidity Pool Aggregation

These bridges deploy smart contracts across multiple blockchains and incentivize users to provide liquidity, dynamically allocating funds based on demand.

This model avoids the fragmented liquidity issue of atomic swaps, offering lower fees and higher cross-chain efficiency. Its success hinges on: decentralized asset management, efficient cross-chain fund balancing, and sufficient liquidity.

Potential risks involve whether the bridge can maintain constant asset control and whether smart contracts across chains contain vulnerabilities.

Lock-and-Mint

Native tokens are locked in a designated contract on the source chain, and synthetic tokens are minted on the target chain. This method is primarily used for token transfers. Examples include $WBTC and $WETH.

Here’s how token transfer works:

1. Users send tokens to the bridge’s contract on the source chain, specifying their receiving address on the target chain.

2. Validators on the target chain verify this information and mint the corresponding wrapped tokens to the user’s specified address, completing the transfer.

3. To return tokens to the source chain, users send the wrapped tokens to the bridge’s contract on the target chain, indicating their wallet address on the source chain.

4. Validators destroy the wrapped tokens, unlock the originally locked tokens on the source chain, and send them to the user’s wallet.

Security depends on network validators. If validators act maliciously or are too centralized and hacked, severe financial losses may occur.

Analysis of Representative Bridges

Gravity Bridge

Built specifically for the Cosmos ecosystem, Gravity Bridge is a neutral bridge connecting Ethereum and Cosmos SDK-based blockchains, filling the gap that prevented Cosmos from communicating with PoW chains. Gravity Bridge deploys immutable Solidity contracts that cannot be altered by any malicious actor. Users lock tokens on Ethereum, and validators sign transactions to mint wrapped tokens across any Cosmos-based chain (e.g., Cosmos, Osmosis, Stargaze), such as $wBTC, $wETH, $DAI, $USDC. These tokens can then be used in Cosmos dApps like Akash Network, Sentinel, Regen, and Osmosis. Similarly, Cosmos-native tokens can be transferred to Ethereum for DeFi yield farming.

Why Use Gravity Bridge?

- Security: Advanced slashing mechanisms ensure validators cannot sign unauthorized bridge messages. The Cosmos ecosystem has active validators who must stake valuable collateral—malicious actors face economic penalties. Anyone can submit evidence via non-protocol messages to slash validators. Node staking is permissionless and censorship-resistant. Each validator proves every deposit event on Ethereum.

- Non-Custodial: No third party controls funds. Users only need to trust the security of Ethereum and Cosmos—both of which are well-established and highly secure.

- Interoperable: BNB was long the only token available across both Ethereum and Cosmos ecosystems. Only after Gravity Bridge launched did Cosmos dApps become accessible to Ethereum users.

- Neutral: The validator set governs the bridge. The Gravity community prioritizes bridge security and efficiency over promoting specific chain DeFi apps, aggregating liquidity across multiple chains.

- Low Fees: Gravity batches withdrawals, bundling multiple messages into single batches, reducing gas costs by 96%.

Stargate

Stargate is the first protocol built on LayerZero, enabling users to securely and easily transfer and swap native tokens across blockchains instantly.

Most current wrapped-token bridges lack true interoperability—they cannot interact with target chain smart contracts, suffer from high costs, and long confirmation times, leading to poor user experience.

Stargate innovatively solves the so-called “impossible triangle” of cross-chain transfers:

- Instant Transaction Confirmation: Immediate confirmation of token transfers on both source and destination chains.

- Unified Liquidity: Shared liquidity pool for the same token across different blockchains.

- Native Token Transfers: No wrapped tokens—all transacted tokens are native.

LayerZero enables Stargate’s instant message passing and seamless UX, as detailed earlier.

Stargate uses its proprietary Delta algorithm to solve unified liquidity and native token bridging. For the same token, all chains share one liquidity pool, with each chain accessing others’ liquidity. The Delta algorithm is a balancing mechanism supporting native token pools, managing liquidity via “soft partitioning” to prevent liquidity drain during concurrent trades. For example, in a network of chains X, Y, and Z, $100 of liquidity on Chain X is virtually split into $50 on Y and $50 on Z. The Delta algorithm monitors each chain’s “virtual balance sheet,” allowing borrowing and repayment across chains as long as liquidity isn’t overdrawn. When a partition balance drops below initial levels, a “debt” arises. When a transfer occurs from source Chain A to target Chain B, incoming tokens first cover any debt on A, with remaining funds distributed across all pools according to weight.

Stargate is a star project in the bridge space, backed by top-tier investors including FTX, a16z, Sequoia, Binance, and Coinbase. Within 10 days of launch, it achieved nearly $4 billion in TVL, ranking 11th among all protocols (18th as of May 14).

Notably, Stargate uses a 2/3 multisig mechanism with few validators, potentially exposing it to risks similar to the Ronin Network private key attack.

cBridge 2.0

cBridge is a cross-chain bridge built on Celer IM. The State Guardian Network (SGN), a core component of Celer IM, is a Tendermint-based PoS chain that monitors on-chain events and offers higher security than multisig or secret-sharing schemes.

SGN as the Arbitrator for cBridge Node Gateway

In version 1.0, cBridge used a centralized gateway to gather operational insights and provide “for reference only” recommendations for using cBridge nodes. However, if a node went offline before completing a transfer, it faced no penalties, and users received no compensation.

Version 2.0 resolves this by using SGN for decentralized and efficient cBridge node scheduling. Nodes register with SGN based on fee preferences and available liquidity, no longer relying on centralized gateways.

User flow during a cross-chain request:

- User queries SGN for current status, obtaining estimated fees and available liquidity.

- If acceptable, the user initiates the first half of an HTLC transfer, setting a maximum fee cap.

- SGN monitors and receives the transaction, assigning one or more registered cBridge nodes based on scheduling rules. This assignment is recorded on both SGN and the user’s HTLC contract.

- Assigned nodes accept and respond by completing the conditional transfer.

- SGN continues tracking until completion, then clears related state data. If a node goes offline prematurely, SGN slashes its bond as compensation for degraded UX and opportunity cost.

Additionally, cBridge 2.0 introduces a “node quality score” formula incorporating factors like fees, response time, and success rate, enabling prioritized node selection to enhance user experience.

This outlines the design for self-hosted LPs running their own nodes.

SGN as Shared Liquidity Pool Manager

Most LPs and users want to provide liquidity without running cBridge nodes themselves. In cBridge 2.0, the decentralized SGN manages shared liquidity pool contracts across multiple chains. LPs treat SGN and its managed pools as a single node, earning fees without operating nodes.

Is using SGN as a centralized liquidity manager safe? First, SGN uses PoS consensus. Token transfers require CELR-stake-weighted multisig signatures—funds are only at risk if over two-thirds of total stake collude maliciously. As cBridge transaction volume and network value grow, the cost of attacking increases, making it one of the highest-security designs today. Unlike multisig or secret-sharing solutions, where validators aren’t economically bonded, SGN’s security scales with network value. Furthermore, multisig signers or secret holders may collude privately for profit. SGN allows new validators to be elected and join via staking and governance without special coordination. However, during market downturns, stake value may fall sharply, potentially dipping below bridge liquidity—users and projects should remain vigilant. Still, as noted in the Celer IM section, the Optimistic Rollup-inspired “quarantine” model ensures dual safeguards: small transfers execute immediately via SGN; large ones undergo enforced delays.

Some existing bridge solutions require LPs to pair token liquidity with another protocol-controlled settlement token in on-chain AMMs, e.g., Thorchain and Hop Protocol. This incurs extra operational costs when adding, removing, or rebalancing liquidity across chains. Thorchain forces LPs to use volatile Rune as settlement token, exposing them to impermanent loss. Hop requires bonders to front liquidity, reducing efficiency since required liquidity is double actual need.

When processing cross-chain requests, cBridge 2.0 uses the entire pool’s liquidity to calculate slippage and pricing, treating LPs as “virtual cBridge nodes” and allocating requests proportionally. Target chain LP balances decrease proportionally to usage, while source chain balances increase. Random sampling and approximation algorithms minimize state changes and costs, ensuring statistical fairness among LPs. This design gives every LP clear visibility into their liquidity allocation, empowering informed decisions when adjusting positions.

In cBridge 2.0, LPs use native token liquidity directly, avoiding impermanent loss. Compared to Hop Protocol, cBridge requires no additional bonder liquidity, achieving maximum capital efficiency.

As discussed, cBridge 2.0 leverages SGN’s blockchain-grade security to monitor message transmission, offering both “SGN as cBridge Node Gateway Arbitrator” (self-hosted mode) and “SGN as Shared Liquidity Pool Manager,” catering to diverse user needs.

cBridge serves as the default bridge on BNBChain’s sidechain BAS. Game projects integrating with BAS default to cBridge, reflecting Binance’s recognition of Celer’s technology.

V. Other Cross-Chain Use Cases

Beyond well-known applications like cross-chain bridges for token transfers, cross-chain messaging protocols enable numerous other inter-chain interactions.

Cross-Chain Aggregators

Help users identify lower-cost, faster cross-chain solutions. Services include Defieye’s Bridge Eye, Bungee, XY Finance.

Cross-Chain DeFi

- ChainHop allows users to one-click swap ETH on Arbitrum for BNB on BNB Chain.

- Deposit assets into Yearn vaults on Ethereum while earning yields on chains like Solana and Avalanche.

- Aperture, a community-driven DeFi strategy marketplace, lets users on any blockchain access supported strategies with one click.

- SynFutures supports multi-chain futures trading.

- Collateralize assets in Compound on Ethereum and borrow DAI on Polygon.

Cross-Chain DAO

- AAVE’s governance outcome on Ethereum is relayed via the AAVE cross-chain governance bridge, allowing Ethereum governance to control Aave markets on Polygon, replacing the previous multisig solution.

- FutureSwap, a decentralized AMM-based trading protocol, achieves cross-chain governance via Celer IM.

Cross-Chain NFTs

- Send NBA Top Shot NFTs from Flow to Ethereum’s NFTfi lending market for collateralized loans.

- Use ENS domain service on blockchains beyond Ethereum.

VI. Notable Risks

On January 8, 2022, Vitalik Buterin posted on Reddit expressing optimism about a multi-chain future but pessimism toward cross-chain. He argued that even under a 51% attack, native tokens on a blockchain remain secure—no matter how much hash power tries to steal your tokens, compliance with protocol rules prevails. Every node follows the 1% that adheres to consensus. However, if Ethereum suffers a 51% attack, Solana-WETH contracts lose their 1:1 backing guarantee, meaning 1 WETH might no longer redeem exactly 1 ETH.

Vitalik is correct. The “lock-and-mint” bridging method carries inherent unavoidable risks. The cross-chain ecosystem is still in a growth phase. As bridges connect more chains, systemic risks from 51% attacks increase. Underlying cross-chain messaging protocols must prioritize connected chain security, continuously improve core code, and build preventive mechanisms. Users should prefer bridges supporting native asset transfers whenever possible.

Vitalik also noted that when bridges accumulate massive liquidity, hackers gain strong incentives to attack for huge profits. Therefore, liquidity providers must assess risks carefully, and users should always revoke approvals after using bridges. Multichain once had a contract vulnerability—users who failed to revoke approvals lost assets.

VII. Conclusion

In 2021, major public blockchains flourished thanks to capital support and developer innovation. Moving forward, each chain will deepen its specialization based on its design, securing its niche. The multi-chain landscape is now established and irreversible. Despite potential risks, cross-chain messaging protocols that connect isolated blockchains are essential foundational infrastructure in a multi-chain world. Demand for robust cross-chain solutions remains strong. In the future, we’ll see increasingly sophisticated cross-chain applications, and the interoperability and composability between blockchains will surely bring new surprises. Let’s look forward to the infinite possibilities of blockchain!

References:

Blockchain Bridges: Building Networks of Cryptonetworks

https://medium.com/1kxnetwork/blockchain-bridges-5db6afac44f8

The Interblockchain Communication Protocol: An Overview

https://ibcprotocol.org/documentation/

What is Cosmos?

https://v1.cosmos.network/intro

Cross-Chain Bridges Explored

https://medium.com/momentum6/cross-chain-bridges-explored-929e6b68dcd1

Everything You Need to Know About the Gravity Bridge Chain

https://blog.cosmos.network/gravity-is-an-essential-force-of-the-cosmos-aligning-all-planets-in-orbits-in-the-composable-b1ca17de18cc

LayerZero- An Omnichain Interoperability Protocol

https://medium.com/layerzero-official/layerzero-an-omnichain-interoperability-protocol-b43d2ae975b6

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News