Is AI infrastructure a bubble or "banding together to buy time"? Dissecting the financial structure behind 3 trillion dollars

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Is AI infrastructure a bubble or "banding together to buy time"? Dissecting the financial structure behind 3 trillion dollars

As tech giants spend over $300 billion this year building AI computing power, with total expected investments exceeding $3 trillion in the next three years, a question arises: is this a replay of the 2000 dot-com bubble, or the largest productivity bet in human history?

This is not a simple binary debate of "bubble vs. no bubble"—the answer may be more complex and sophisticated than you think. I don't have a crystal ball to predict the future. But I've tried to deeply unpack the underlying financial structure of this boom and build a framework for analysis.

The article is long and detailed. Here are the key conclusions upfront:

-

In broad terms, I don’t believe this is a major bubble. But certain segments carry high risk.

-

More precisely, current AI infrastructure resembles a "rallying together + buying time" long march. Tech giants (Microsoft, Google, Meta, Nvidia, etc.) use financial engineering to leverage massive capital, but outsource primary credit risk to special-purpose vehicles (SPVs) and capital markets, tightly aligning incentives across all participants.

-

"Buying time" means they’re betting that their cash flows and external investors’ patience will last until the day when "AI genuinely boosts productivity."

-

If they win, AI delivers on its promise and tech giants reap the biggest rewards. If they lose (AI progress falls short or costs remain too high), the first to suffer are the external financiers providing capital.

-

This isn’t a 2008-style bubble caused by excessive bank leverage and single-point failure. It’s a massive direct-financing experiment led by the smartest, most cash-rich companies on Earth, using complex off-balance-sheet financing strategies to break risks into tradable pieces and distribute them among various investors.

-

Even if it's not a bubble, that doesn't mean all AI infrastructure investments will yield good ROI.

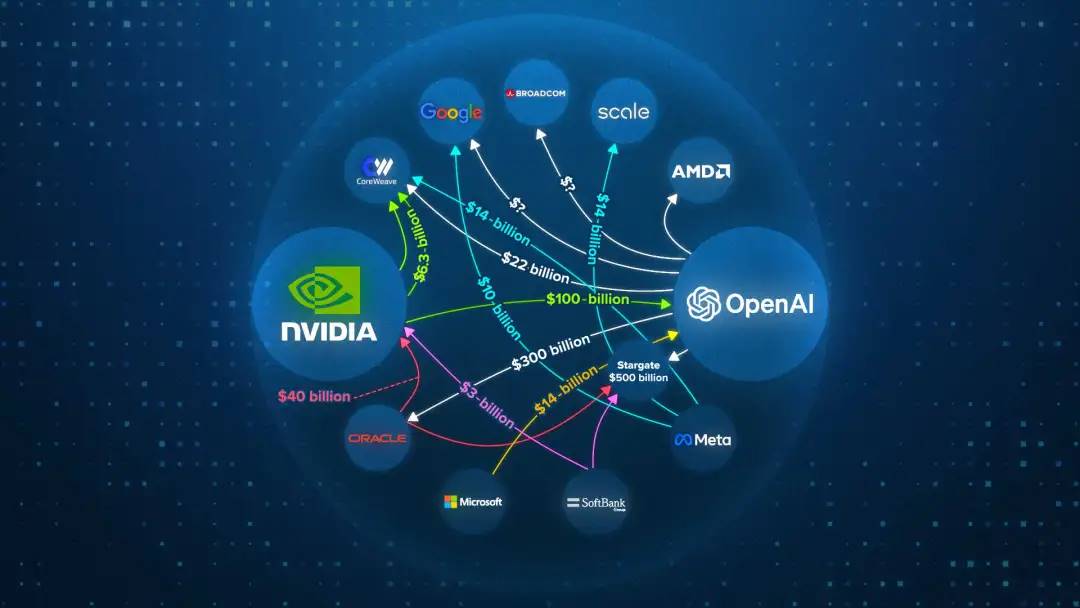

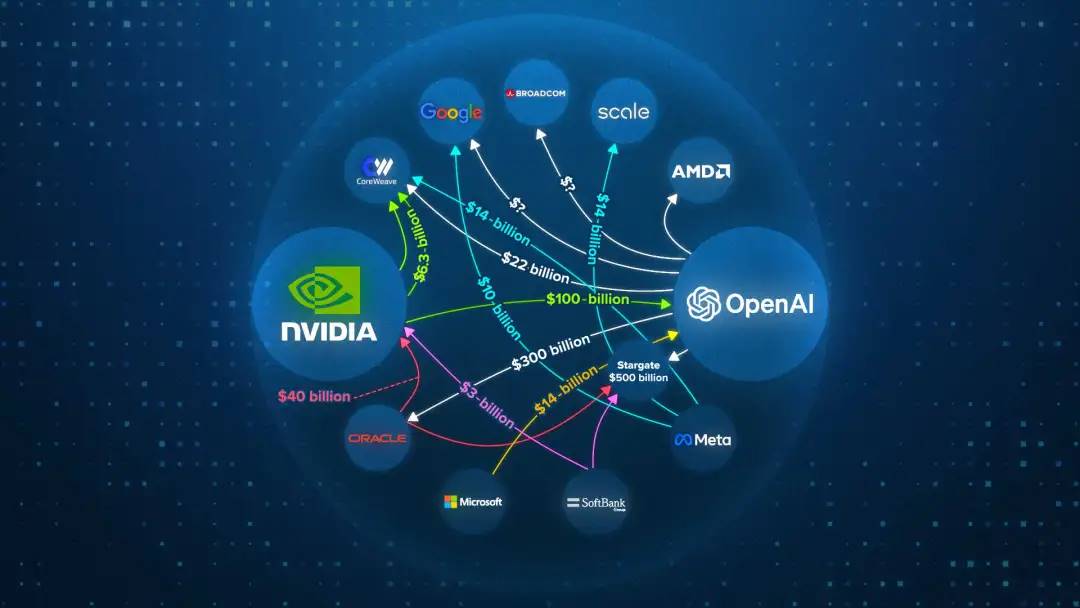

01 Understanding the Core: The "Rallying Together" Incentive Mechanism

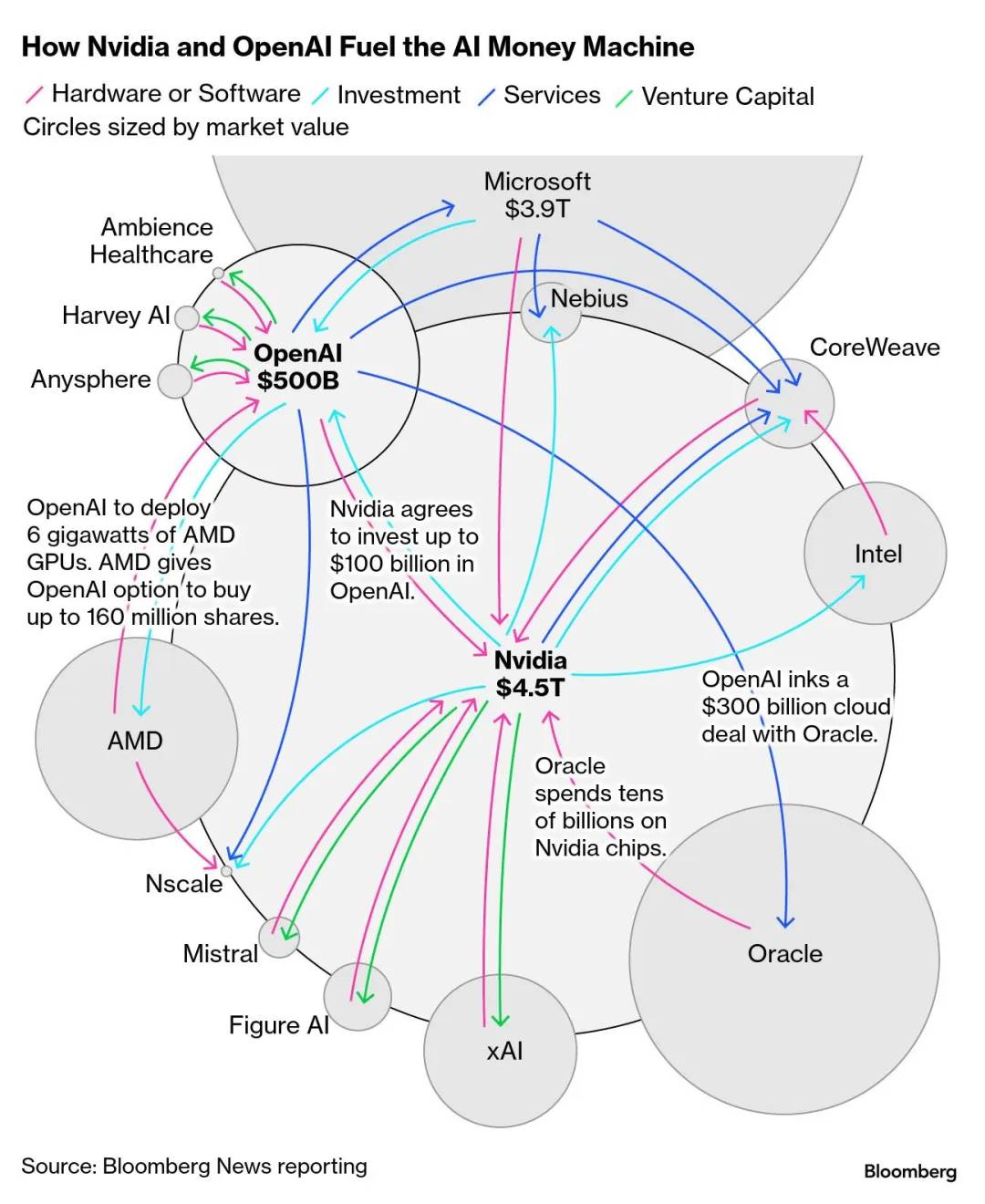

"Rallying together" refers to how this AI infrastructure tightly binds the interests of five parties:

-

Tech giants (Meta, Microsoft, Google) and their large model partners (OpenAI, xAI): They need computing power but don’t want to make one-time massive investments.

-

Chip suppliers (Nvidia): They require sustained large orders to justify their valuations.

-

Private equity funds (Blackstone, Blue Owl, Apollo): They need new asset classes to grow assets under management (AUM) and collect higher fees.

-

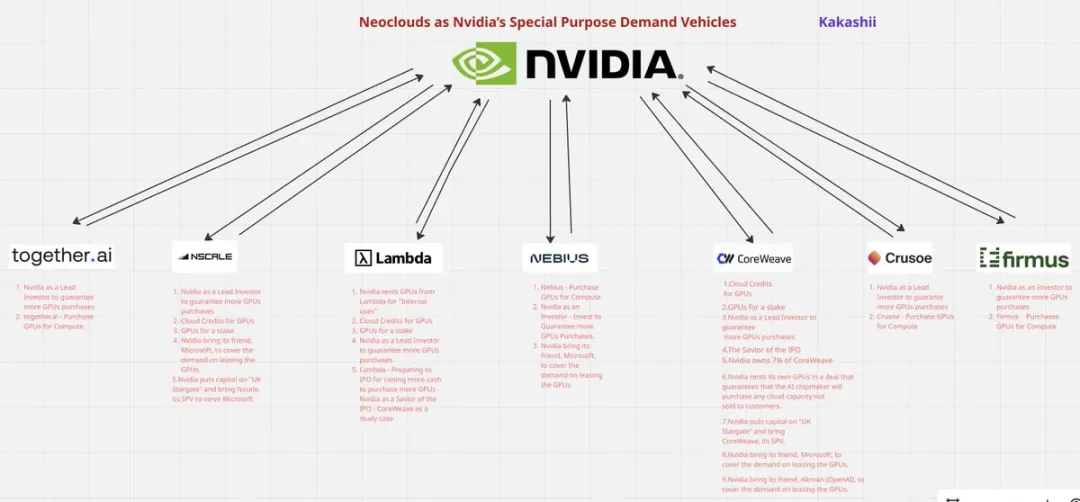

Neoclouds (CoreWeave, Nebius) and hybrid cloud providers (Oracle Cloud Infrastructure): They provide infrastructure and compute capacity, but also rely on long-term contracts from big tech to secure financing.

-

Institutional investors (pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, traditional funds like BlackRock): They seek stable returns above government bond yields.

These five parties form an "interest共同体," for example:

-

Nvidia gives CoreWeave priority supply and invests in its equity

-

Microsoft signs long-term contracts with CoreWeave and helps it raise funding

-

Blackstone provides debt financing while raising capital from pension funds

-

Meta and Blue Owl jointly establish an SPV, sharing risks

-

OpenAI and other large model players continuously raise the bar for model parameters, inference capability, and training scale—effectively increasing the industry-wide threshold for computing demand. Especially under deep collaboration with Microsoft, this “outsourced technology, internalized pressure” model allows OpenAI to become the ignition point of a global capital expenditure race without spending money. It is not a funder, yet acts as the de facto curator driving up leverage across the board.

No one can stay immune—this is the essence of "rallying together."

02 Capital Architecture — Who Is Paying? Where Does the Money Flow?

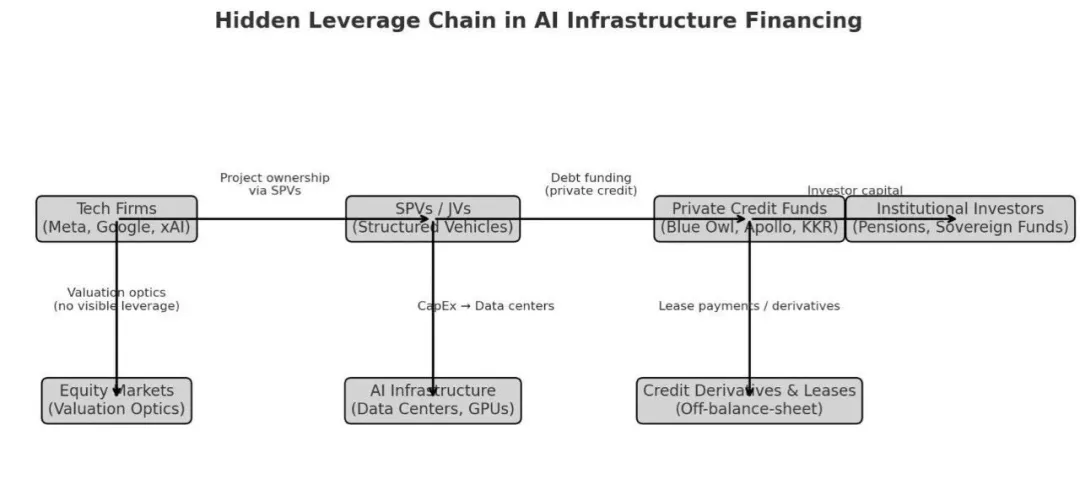

To understand the overall architecture, let’s start with the fund flow diagram below.

Tech giants need astronomical amounts of computing power and have two options:

-

Build data centers in-house: This is the traditional model. Advantages include full control; disadvantages are slow construction and placing all capital expenditures and risks directly on their balance sheets.

-

Seek external supply: Giants aren’t simply renting servers—they’ve created two core models of "external suppliers." This is the current trend and our main focus.

The first is SPVs (Special Purpose Vehicles)—purely financial instruments. Think of them as special entities established specifically for a "single project, single customer."

-

Business model: For instance, if Meta wants to build a data center but doesn’t want to pay a huge sum upfront, it partners with an asset manager to create an SPV. The SPV’s sole mission is building and operating a data center exclusively for Meta. Investors receive high-quality debt backed by rental cash flows (a hybrid of corporate bonds and project finance).

-

Customer type: Extremely concentrated, usually just one (e.g., Meta).

-

Risk level: Survival depends entirely on the creditworthiness of a single customer.

The second is Neoclouds (like CoreWeave, Lambda, Nebius)—independent operating companies (OpCos) with their own operational strategies and full decision-making autonomy.

-

Business model: For example, CoreWeave raises capital (equity and debt) to buy large quantities of GPUs and leases them to multiple customers under "minimum commitment/reserved capacity" contracts. More flexible, but with volatile equity value.

-

Customer type: Theoretically diversified, but early on heavily reliant on tech giants (e.g., Microsoft’s early support for CoreWeave). Due to smaller scale and lacking a single wealthy backer like SPVs, Neoclouds are more dependent on upstream suppliers (Nvidia).

-

Risk level: Risks are spread across multiple customers, but survival depends on operational ability, technology, and equity valuation.

Despite differing legal and operational structures, both share the same business essence: serving as "external compute suppliers" for tech giants, moving massive GPU procurement and data center construction off the giants’ balance sheets.

So where do SPVs and Neoclouds get their money?

The answer is not traditional banks, but private credit funds. Why?

After 2008, Basel III imposed strict capital adequacy requirements on banks. Providing large-scale, highly concentrated, long-tenor loans like these would require prohibitively high capital reserves.

The business that banks "can’t do" or "dare not do" created a huge vacuum. Private credit giants like Apollo, Blue Owl, and Blackstone stepped in—they aren’t bound by banking regulations and can offer more flexible, faster, albeit higher-interest financing, secured by project rents, GPUs/equipment, or long-term contracts.

For them, this is an attractive opportunity—many already have experience in traditional infrastructure financing, and this theme allows AUM to grow several-fold, significantly increasing management fees and carried interest.

Where do these private credit funds ultimately source their capital?

The answer lies with institutional investors (LPs)—pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, insurers, and even retail investors (e.g., through BlackRock’s private credit ETFs, which include Meta’s 144A private bond: Beignet Investor LLC 144A 6.581% 05/30/2049).

Thus, the risk transmission chain is clear:

(Ultimate risk bearers) Pension funds / ETF investors / Sovereign funds → (Intermediaries) Private credit funds → (Financed entities) SPVs or Neoclouds (e.g., CoreWeave) → (End users) Tech giants (e.g., Meta)

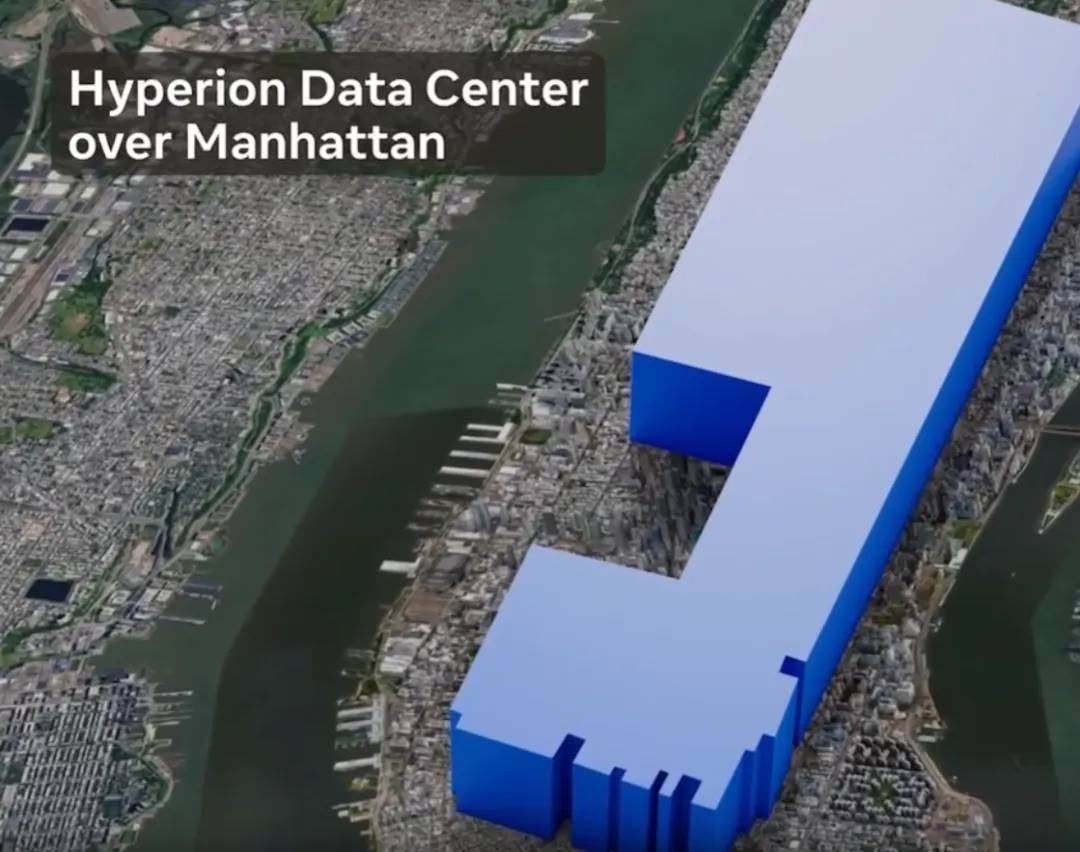

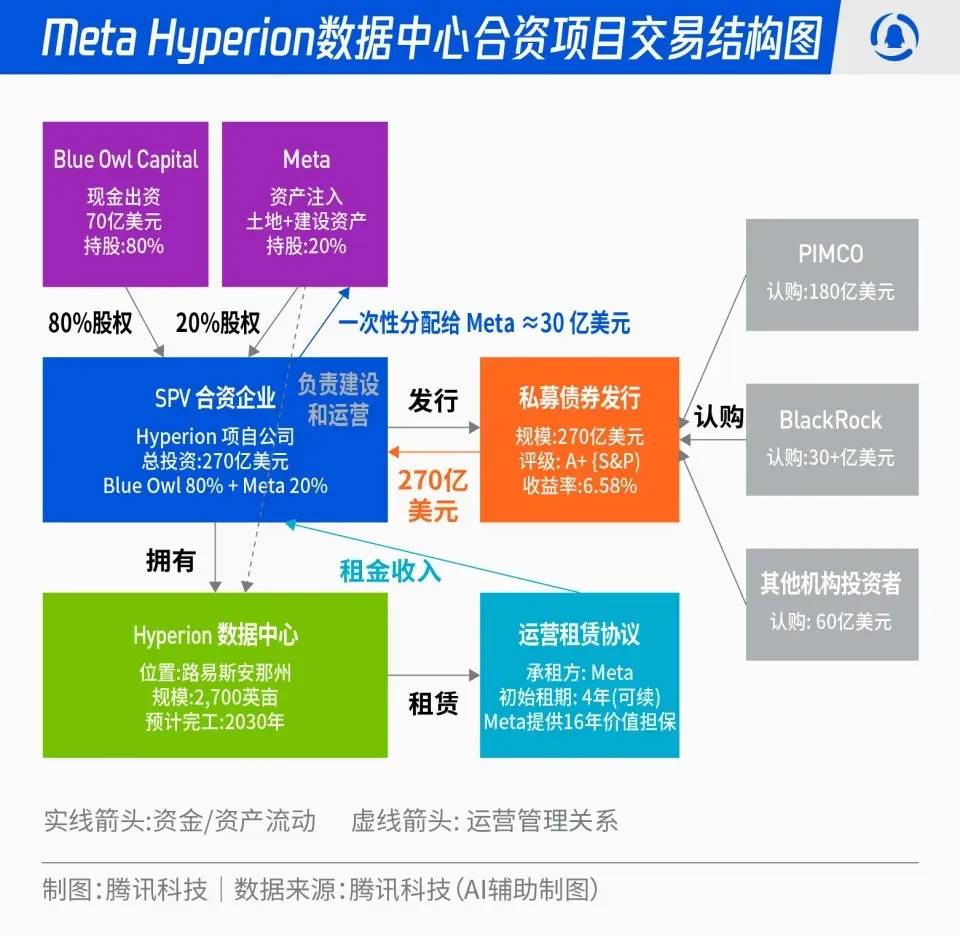

03 SPV Case Study — Meta’s Hyperion

To understand the SPV model, Meta’s "Hyperion" project serves as an excellent case study (with ample public information):

-

Structure/Equity: Meta and Blue Owl co-manage a JV (Beignet Investor LLC). Meta holds 20% equity, Blue Owl 80%. Bonds issued via 144A SPV structure. JV builds assets; Meta leases long-term. Capital expenditures during construction belong to the JV; after lease financing begins, assets gradually transfer onto Meta’s balance sheet.

-

Scale: Approximately $27.3 billion in bonds (144A private placement) plus ~$2.5 billion in equity—one of the largest single corporate bond/private credit project financings in U.S. history. Maturity in 2049—this ultra-long tenor essentially "locks in the hardest time-related risks."

-

Interest rate/Rating: Debt rated A+ by S&P (high rating enables insurer allocations), coupon rate ~6.58%.

-

Investor composition: PIMCO subscribed $18 billion; BlackRock ETFs collectively over $3 billion. For these investors, it offers highly attractive, stable, high-quality returns.

-

Cash flow and lease: What Blue Owl values is not potentially depreciating GPUs (I believe some market concerns about overly optimistic GPU depreciation assumptions miss the point—GPUs are just hardware, while AI’s overall value lies in hardware + models; falling prices of older GPUs due to iteration don’t necessarily mean declining value of final AI applications), but rather the SPV’s cash flows supported by Meta’s long-term lease (starting from 2029). Construction-phase funds are pre-allocated to U.S. Treasuries to reduce risk. This structure blends corporate bond liquidity with project finance protections, and remains 144A-for-life (limited investor pool).

Why is short-term risk extremely low in such structures?

Because in this setup, Hyperion has a simple task: collect rent from Meta on one hand, pay interest to Blue Owl on the other. As long as Meta survives (extremely unlikely to fail in the foreseeable future), cash flows remain rock solid. No need to worry about AI demand fluctuations or GPU price drops.

This 25-year ultra-long-term, rent-amortized debt structure locks in near-term refinancing risks as long as rent keeps flowing and interest payments continue. This is the essence of "buying time" (allowing AI-generated value to gradually catch up with financial structures).

Meanwhile, Meta uses its credit strength and strong cash flows to obtain massive long-term financing without going through traditional capex routes. Although under modern accounting standards (IFRS 16), long-term leases eventually appear as "lease liabilities" on the balance sheet, the advantage is that tens of billions in upfront capex pressure, construction risks, and financing operations are initially shifted to the SPV.

By converting a one-time massive capex into 25 years of installment lease payments, cash flow is greatly optimized. Then it bets whether these AI investments can generate sufficient economic returns within 10–20 years to cover principal and interest (given the bond’s 6.58% coupon rate, considering operating expenses, EBITDA-based ROI needs to be at least 9–10% for equity holders to achieve decent returns).

04 Neocloud Buffer — OpCo Equity Risk

If the SPV model is about "credit transfer," then the Neocloud model (CoreWeave, Nebius) represents "further risk layering."

Take CoreWeave as an example—its capital structure is far more complex than SPVs. Multiple rounds of equity and debt financing involve Nvidia, VCs, growth funds, and private credit funds, forming a clear risk buffer hierarchy.

If AI demand disappoints or new competitors emerge, causing CoreWeave’s revenue to plummet and unable to meet high interest payments:

-

First, equity value evaporates: CoreWeave’s stock crashes. This is the "equity buffer"—absorbing the initial shock. The company may be forced to raise capital at a discount, severely diluting existing shareholders or wiping them out entirely. Compared to SPVs, which lack access to public markets, Neoclouds have thinner equity buffers.

-

Next, creditors take losses: Only after equity is fully wiped out and CoreWeave still cannot repay debts do private lenders like Blackstone face losses. However, these funds typically demand strong collateral (latest GPUs) and senior repayment rights.

CoreWeave and Nebius both follow a "secure long-term contracts first, then raise financing" approach, rapidly expanding via capital markets. The brilliance of this structure is that tech giant customers achieve better capital efficiency—leveraging future purchase commitments to drive additional capex without spending money upfront, limiting systemic contagion risk.

Conversely, Neocloud shareholders must recognize they occupy the most volatile—and thrilling—seat at the table. They bet on hypergrowth, pray for flawless financial execution (debt rollovers, equity issuances), and carefully monitor debt maturity profiles, collateral scope, contract renewal windows, and customer concentration to better assess risk-return trade-offs.

We might also ask: If AI demand grows slower than expected, which marginal capacity will be abandoned first—SPV or Neocloud? And why?

05 Oracle Cloud: The Unexpected Challenger Among Cloud Players

While everyone focuses on CoreWeave and the three major cloud giants, an unexpected "dark horse" is quietly rising: Oracle Cloud.

It’s neither a Neocloud nor part of the top-tier tech giants, yet through highly flexible architectural design and deep collaboration with Nvidia, it has secured compute contracts with Cohere, xAI, and even parts of OpenAI’s workload.

Especially when Neoclouds face tightening leverage and traditional cloud capacity becomes insufficient, Oracle positions itself as a neutral, interchangeable alternative, becoming a crucial buffer layer in the second wave of AI compute supply chains.

Its emergence shows that this compute race isn’t limited to a three-way battle—non-traditional but strategically significant players like Oracle are quietly gaining ground.

But remember, this game isn’t played solely in Silicon Valley—it extends into global financial markets.

The coveted implicit government guarantee

Finally, in this game dominated by tech giants and private finance, there’s a potential "trump card"—governments. While OpenAI recently stated publicly it "does not and does not want" government loan guarantees for data centers—the discussions were about potential chipmaker guarantees, not data centers—I believe that in their (or similar players’) original plans, "bringing governments into the rally" was always an option.

Why? If AI infrastructure scales beyond what private credit can support, the only path forward is elevating it to a national competition. Once AI leadership is framed as "national security" or a "21st-century moonshot," government intervention becomes natural.

The most effective form of intervention isn’t direct funding, but providing "guarantees." This brings a decisive benefit: drastically lowering financing costs.

Investors around my age should recall Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae. These "government-sponsored enterprises" (GSEs) weren’t official U.S. government agencies, but markets widely believed they had "implicit government backing."

They bought mortgages from banks, packaged them into MBS, guaranteed them, sold them in public markets, and recycled capital back into mortgage lending, increasing available credit. Their existence amplified the impact of the 2008 financial crisis.

Imagine a future "National AI Compute Company" backed by implicit government guarantees. Its bonds would be treated as quasi-sovereign debt, with interest rates approaching U.S. Treasury levels.

This would fundamentally change the earlier concept of "buying time until productivity rises":

-

Extremely low financing costs: Lower borrowing costs reduce the required pace of AI productivity gains.

-

Nearly infinite time extension: More importantly, ultra-low-cost perpetual rollovers effectively buy almost unlimited time.

In other words, this makes the probability of catastrophic collapse much lower—but if collapse does occur, the fallout could be tens of times larger.

06 Trillion-Dollar Bet — The Real Key: "Productivity"

All the financial structures discussed—SPVs, Neoclouds, private credit—are ultimately answering just one question: "How do we pay?"

The fundamental question determining whether AI infrastructure becomes a bubble is: "Can AI truly enhance productivity?" and "How fast?"

All 10- to 15-year financing arrangements are essentially "buying time." Financial engineering gives tech giants breathing room—results don’t need to materialize immediately. But time comes at a cost: Investors from Blue Owl and Blackstone (pension funds, sovereign funds, ETF holders) expect steady interest returns; Neocloud equity investors demand multi-fold valuation growth.

The "expected return rates" demanded by these financiers represent the minimum productivity hurdle AI must clear. If AI-driven productivity improvements fail to keep pace with high financing costs, this intricate structure will begin collapsing from its weakest point ("equity buffer").

In the coming years, watch these two areas closely:

-

Pace of "application solutions" rollout: Powerful models (LLMs) alone aren’t enough. We need actual software and services compelling enough for businesses to pay. Widespread adoption is needed to generate cash flows large enough to service massive infrastructure debts.

-

Constraints from external limitations: AI data centers are power-hungry beasts. Do we have enough electricity to sustain exponential compute growth? Can grid upgrades keep pace? Will Nvidia GPUs and other hardware hit supply bottlenecks, falling behind financial timelines? Supply-side risks could burn through all "bought time."

In short, this is a race between finance (financing costs), physics (power, hardware), and business (real-world application).

We can roughly quantify how much productivity improvement AI must deliver to avoid a bubble:

-

According to Morgan Stanley estimates, cumulative AI investment could reach $3 trillion by 2028.

-

Meta’s SPV bond cost is around 6–7%, while Fortune reports CoreWeave’s average debt rate is about 9%. Assuming most private credit demands 7–8% returns with a 3:7 equity-to-debt ratio, AI infrastructure ROI (calculated as EBITDA against total capex) must reach 12–13% for equity returns to exceed 20%.

-

Required EBITDA = $3 trillion × 12% = $360 billion; assuming 65% EBITDA margin, corresponding revenue ≈ $550 billion;

-

With U.S. nominal GDP around $29 trillion, this implies AI-enabled output must sustainably add ~1.9% of GDP.

This bar isn’t trivial, but it’s not fantasy either (global cloud industry revenue was ~$400 billion in 2025—meaning we’d need AI to generate one to two additional cloud-sized industries). The key lies in synchronizing application monetization speed and overcoming physical bottlenecks.

Risk scenario stress test: What if "time" runs out?

All these financial structures bet that productivity will outpace financing costs. Let’s simulate ripple effects if AI productivity lags expectations:

Scenario One: AI productivity arrives "slowly" (e.g., scales in 15 years, but many financings are 10-year terms):

-

Neoclouds fall first: Highly leveraged independent operators like CoreWeave see revenues fail to cover high interest, burning through their "equity buffer," leading to debt defaults or discounted restructurings.

-

SPVs face rollover risk: When debts like Hyperion mature, Meta must decide whether to refinance at higher rates (after witnessing Neocloud failures), eroding core business profits.

-

Private credit fund LPs suffer heavy losses; tech stock valuations sharply decline. This would be an "expensive failure," but not trigger systemic collapse.

Scenario Two: AI productivity is "disproven" (technological stagnation or unsolvable cost/scaling issues):

-

Tech giants may opt for "strategic default": The worst-case scenario. Giants like Meta may judge continued rent payments as a bottomless pit and forcibly terminate leases, forcing SPV debt restructuring.

-

SPV bonds crash: Bonds like Hyperion, previously seen as A+-rated, instantly decouple from Meta’s credit, collapsing in price.

-

This could completely destroy the private credit "infrastructure financing" market and very likely trigger a confidence crisis in financial markets through the linkages described earlier.

The purpose of these tests is to transform the vague "is it a bubble?" question into concrete scenario analysis.

07 Risk Thermometer: Practical Checklist for Investors

For tracking shifts in market confidence, I personally monitor five indicators as a "risk thermometer":

-

Pace of AI project productivity realization: Including acceleration or deceleration in large model firms' projected revenues (linear vs. exponential growth), and performance of different AI products and projects.

-

Neocloud stock prices, bond yields, announcements: Large orders, defaults/recontracting, debt refinancing (some private bonds mature around 2030—needs close watching), pace of equity raises.

-

Secondary market pricing/spreads of SPV bonds: Whether 144A private bonds like Hyperion trade above par, transaction activity, ETF holdings trends.

-

Changes in long-term contract quality: Take-or-pay ratios, minimum lock-up periods, customer concentration, price adjustment mechanisms (adjustments for electricity rates, interest rates, pricing relative to inflation).

-

Power infrastructure progress and potential tech breakthroughs: As the most likely bottleneck, monitor policy signals on power transformation, transmission/distribution, and electricity pricing. Also track any new technologies that could drastically reduce power consumption.

Why isn’t this a repeat of 2008?

Some may draw parallels to the 2008 bubble. I believe this analogy could lead to misjudgment:

First, the nature of core assets differs: AI vs. housing

The 2008 subprime crisis centered on "housing." Houses themselves contribute little to productivity (rental income grows very slowly). When home prices detached from household income fundamentals and were layered into complex financial derivatives, a bubble burst was inevitable.

AI’s core asset is "compute power"—a "production tool" for the digital age. As long as you believe AI has a high probability of substantially boosting societal productivity in the future (software development, drug discovery, customer service, content creation), concern is unwarranted. This is a "pre-spending" on future productivity, anchored in real fundamentals—even if not yet fully realized.

Second, the critical nodes in financial structures differ: Direct financing vs. banks

The 2008 bubble spread through key nodes—banks. Risk propagated via "indirect bank financing." The collapse of one bank (e.g., Lehman) triggered a loss of trust in all banks, freezing interbank markets and ultimately causing a systemic financial crisis (including liquidity crisis) affecting everyone.

Today’s AI infrastructure financing relies primarily on "direct financing." If AI productivity is disproven, CoreWeave collapses, and Blackstone defaults on $7.5 billion in debt, this would be a massive loss for Blackstone’s investors (pension funds).

Post-2008, the banking system is indeed healthier, but we shouldn’t oversimplify and assume risks can be fully "contained" within private markets. For example, private credit funds themselves may use bank leverage to amplify returns. If AI investments broadly fail, these funds’ massive losses could still spill over through two channels:

-

Leverage default: Fund defaults on bank leverage financing, transmitting risk back to the banking system.

-

LP shocks: Pension funds and insurers suffer massive losses, worsening their balance sheets, prompting them to sell other assets in public markets, triggering chain reactions.

Therefore, a more accurate statement is: "This isn’t a 2008-style single-point-triggered, system-wide frozen interbank liquidity crisis." The worst case would be an "expensive failure," with lower contagion and slower spread. But given the opacity of private markets, we must remain highly vigilant toward this new form of slow-moving systemic risk.

Investor implications: Which layer of this system are you on?

Let’s return to the original question: Is AI infrastructure a bubble?

Bubbles form and burst due to huge gaps between expected and actual outcomes. Broadly speaking, I don’t think it’s a bubble—it’s more like a sophisticated, high-leverage financial setup. But from a risk perspective, while certain segments warrant caution, we shouldn’t ignore the potential "negative wealth effect" from localized bubbles.

For investors, in this multi-trillion-dollar AI infrastructure race, you must know what you're betting on depending on your position:

-

Tech giant stocks: You’re betting AI productivity will outpace financing costs

-

Private credit: You earn stable interest, but bear the risk that "time may run out."

-

Neocloud equity: You’re the highest-risk, highest-return first buffer layer.

In this game, position determines everything. Understanding this chain of financial structures is the first step to finding your place. And recognizing who is "curating" this show is key to judging when the game might end.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News