Is Binance doing evil?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Is Binance doing evil?

Doing nearly unbiased research will take you much further than any machine learning approach.

Author: ltrd

Translation: Block unicorn

All long-term consistently profitable people know that unbiased, emotion-free decision-making is key to sustaining a trading career. You must break fixed thought patterns and continuously re-evaluate risk-reward and the likelihood of unfavorable outcomes. For this reason, a well-structured research process is essential for every successful trader.

But why am I speaking to you in this way—and why have I titled this article "Is Binance evil?"

The reason is simple. Over the past few weeks, I've observed strong emotions surrounding Binance and other exchanges. Some arguments against exchanges—especially Binance—are indeed valid, but I keep seeing biased reasoning and conclusions. So I decided to conduct a simple, transparent study on one hypothesis:

H₀: "Binance is evil and negative for projects listed on the exchange."

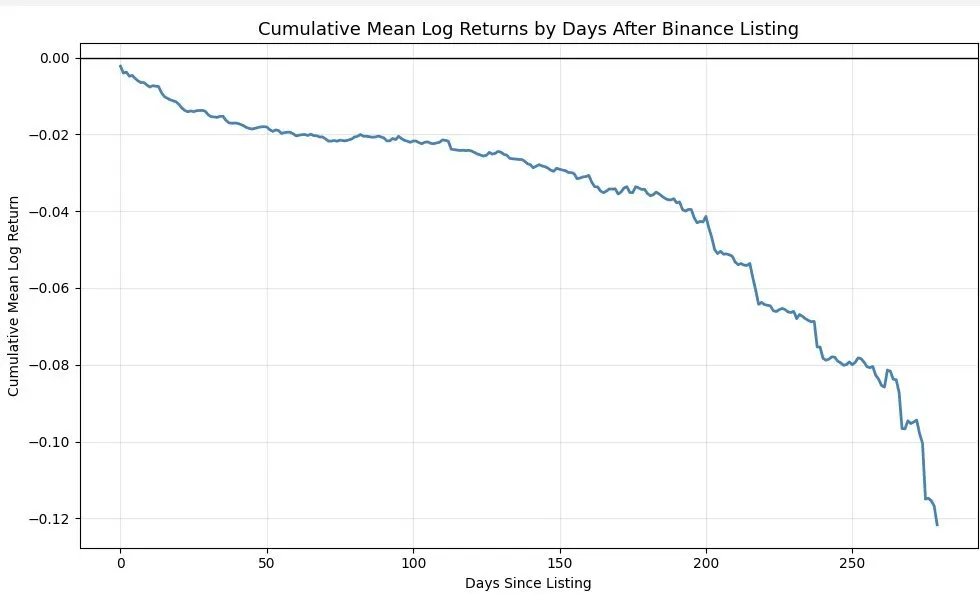

The first thing that motivated me to do this study was a post by Scott Phillips (I actually really like your posts and your thinking—this isn't personal, I hope you can forgive me). He shared a visually appealing chart showing the average price movement of all tokens during their first 300 days after being listed on Binance. The chart itself has no issues—I enjoy this kind of analysis—but one phrase made me uncomfortable: "Binance is a cancer in the industry."

I just don't see how the data in that chart supports such a conclusion.

Imagine you walk into my office (which many people do every day) and tell me: "Tom, look at this chart—Binance is a cancer in the industry."

You'd better have already backed up everything on your work laptop because you'll never touch it again. This article isn't really about Binance—it's about testing a hypothesis and verifying whether it holds. It's about methodological integrity and how to convince others that your argument is sound.

Before we begin, I want you to critique my analysis. That's exactly what we do in our research meetings. I won't get upset—I'm used to constructive criticism, I don't even care anymore; I just want to make sure my analysis is correct so I can learn from it. Your only goal should be to examine it closely and point out every possible flaw in my reasoning. I'm not here to prove Binance isn't evil. I just want to test whether this hypothesis holds.

Whenever I see this type of chart, I always think: there's a missing random correction here.

What do I mean by that? I want to look at randomly selected listing data from similar exchanges and subtract those results from the Binance dataset. That’s how you eliminate bias. In our case, it’s not truly random because we can easily calculate all factors related to listings on other exchanges. Usually in high-frequency trading, you can't "calculate everything," so I call this a random correction.

When conducting research, you need to clearly state your assumptions:

-

I included all products listed on Binance (spot market) since January 1, 2022. Why this date? Because I didn’t want confirmation bias by selecting data from 2020–2021, where I already know the outcome would clearly be positive and wouldn't represent the current market.

-

I only included USDT pairs.

-

I only selected products traded for over 90 days.

-

I excluded the first day (that's why all charts start at 0).

Why? Because exchanges handle opening prices differently. Some "artificially" set an initial trade far below fair value just to make the chart show a huge spike at listing—completely fake. Some announce listings long before or right at launch, making it impossible to effectively separate announcement effects.

Removing the first day makes the analysis cleaner and more comparable. Of course, you can propose your own approach.

After completing the analysis, I obtained the following results:

This shows the cumulative return of all tokens meeting my criteria during their first 90 days after listing on Binance's spot market. What do we see? Massive—absolutely massive—selling pressure from the start. After a few days, it stabilizes slightly, then we enter a steady downtrend. Why? Partly due to the overall cryptocurrency market trend. On average, tokens tend to drift downward after listing. Also, I selected all tokens listed after January 1, 2022—right after a bull market—so the overall environment wasn't very favorable.

Now, let’s talk about my biggest concern—lack of random correction. To me, without random correction, it’s not real research. Even if you show me your last 100 runs with an average of 10.50, I can’t judge unless I see it relative to the broader market. Without a benchmark, there’s no judgment.

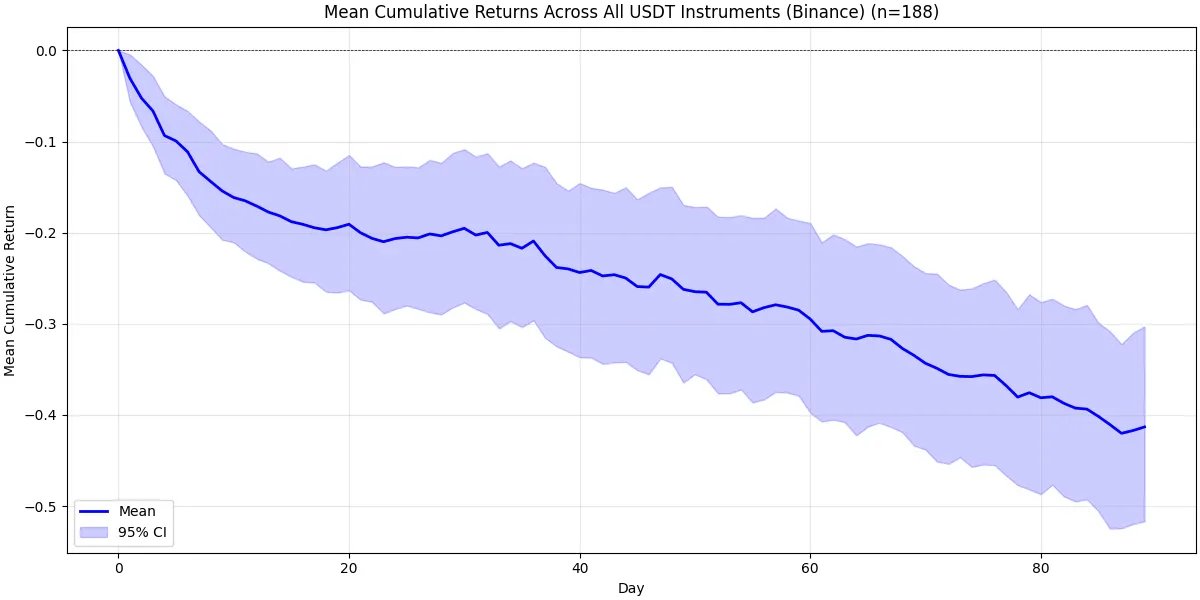

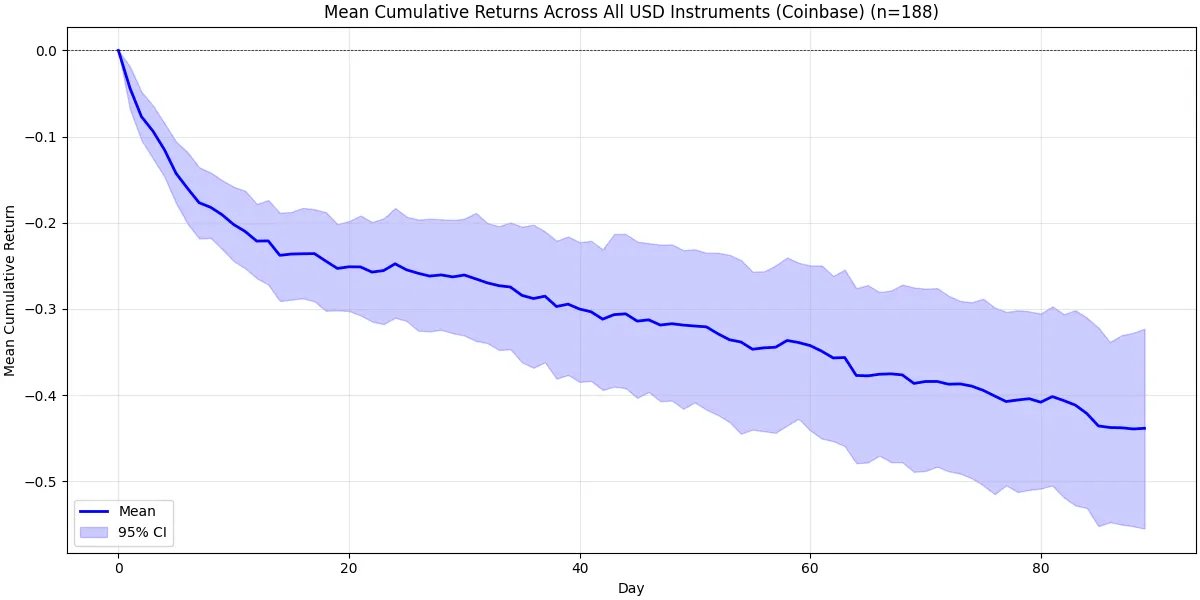

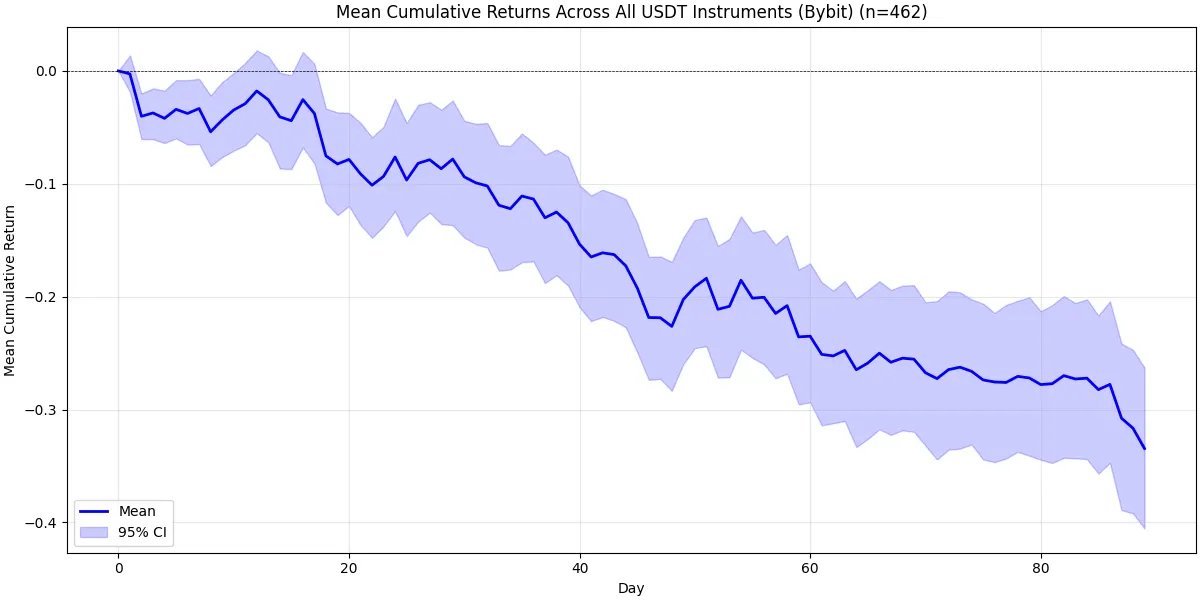

In this case, the "broader market" should be other comparable exchanges—such as Coinbase and Bybit. Therefore, to do this properly, we need to perform the exact same calculation for Bybit and Coinbase (under identical conditions). Let’s look at the charts below.

As you can see, Coinbase’s chart looks much worse than Binance’s. Around 20 days after listing, expected returns drop to about -25% (and the upper confidence interval is still around -20%). After that, we see the same pattern again—brief stabilization followed by a slow downtrend, just like on Binance.

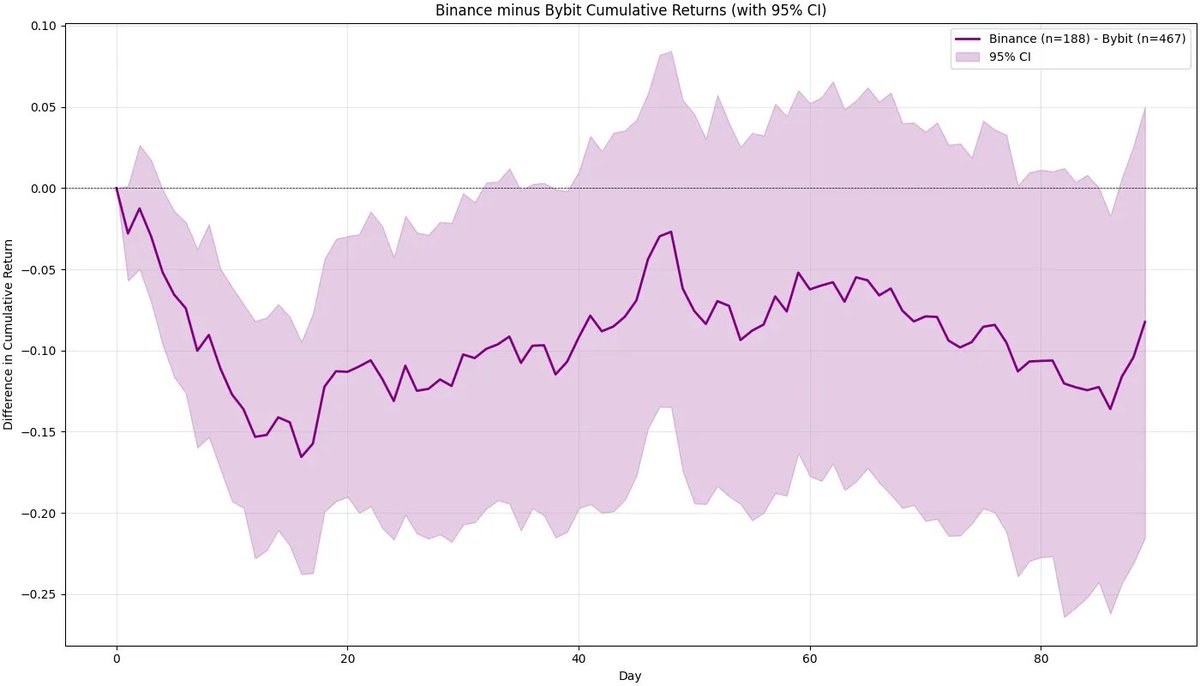

Bybit is slightly different. After 90 days, expected returns still fall sharply, but the initial selling pressure is less severe. Based on data and intuition, I believe Coinbase is far more comparable to Binance than Bybit is.

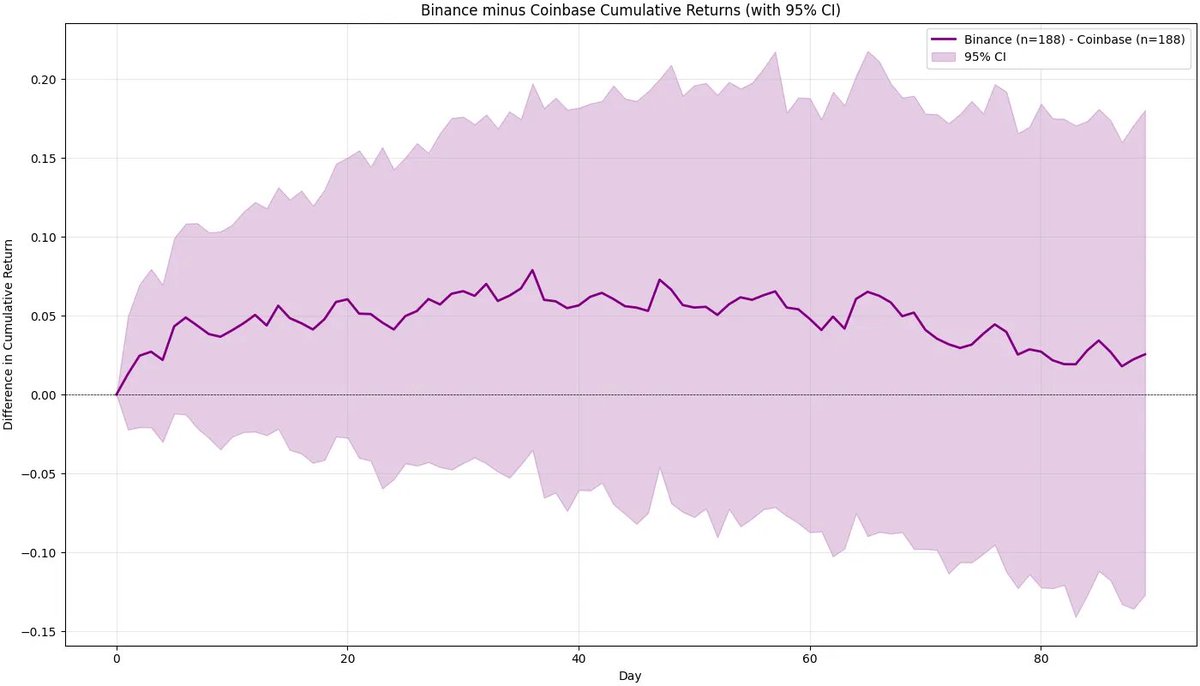

Now, let’s directly compare these exchanges with Binance. For random correction, simply subtract the above results from the main Binance analysis. The figure below illustrates this. Intuitively, what we now get is the net impact of Binance relative to each exchange (Bybit / Coinbase).

You can clearly see—especially in the case of Coinbase—that Binance’s impact is positive, not negative. Selling pressure on Coinbase is far greater than on Binance. Of course, once confidence intervals are considered, this difference isn't statistically significant at the 95% confidence level—but the conclusion remains quite clear: listings on Binance perform better than listings on Coinbase.

For Bybit, we see it performs noticeably better in the first few days after listing. However, the difference grows quickly, and while we might say Bybit outperforms Binance in the short term, the effect isn't particularly strong.

After applying random correction, we absolutely cannot conclude that Binance is "evil" compared to other exchanges—especially Coinbase—since projects listed on Coinbase clearly perform worse. Now, let’s discuss something important—something we don’t talk about enough.

The Curse of Being the Ultimate Goal

Imagine talking to a project team that hasn’t launched yet. What would you expect them to say? The answer is almost always:

"Our ultimate goal is to list on Binance (or Coinbase, Upbit)."

This statement is crucial when discussing Binance’s impact on a project. Everyone waits for this moment. If you're a major investor or project founder and you truly believe you’ll eventually land on Binance, Coinbase, or Upbit, what motivation do you have to sell tokens after listing on Bybit? I’d say almost none—except perhaps a small portion forced by operational expenses.

This is why you see massive selling pressure on Binance and Coinbase, while Bybit sees almost none (Bitget, KuCoin, or Gate probably also have little). Yet, according to our methodology, even after removing announcement-day effects, Binance listings perform better than Coinbase listings. Now, I’d definitely ask you:

"What percentage of tokens do you estimate an average large investor or founder wants to sell after achieving their ultimate listing goal?"

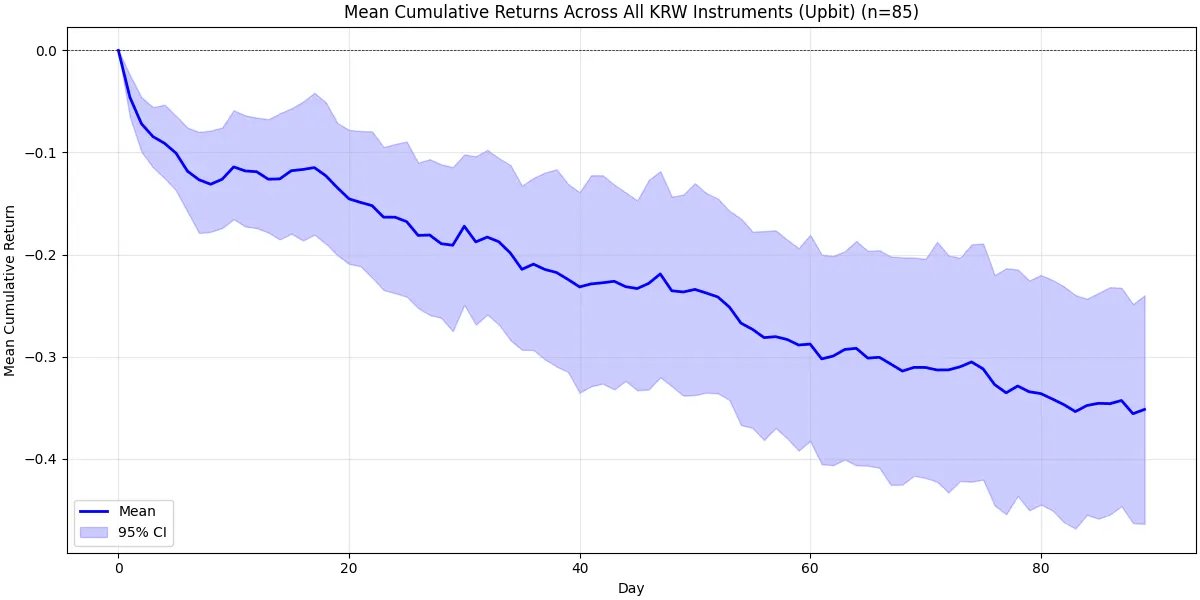

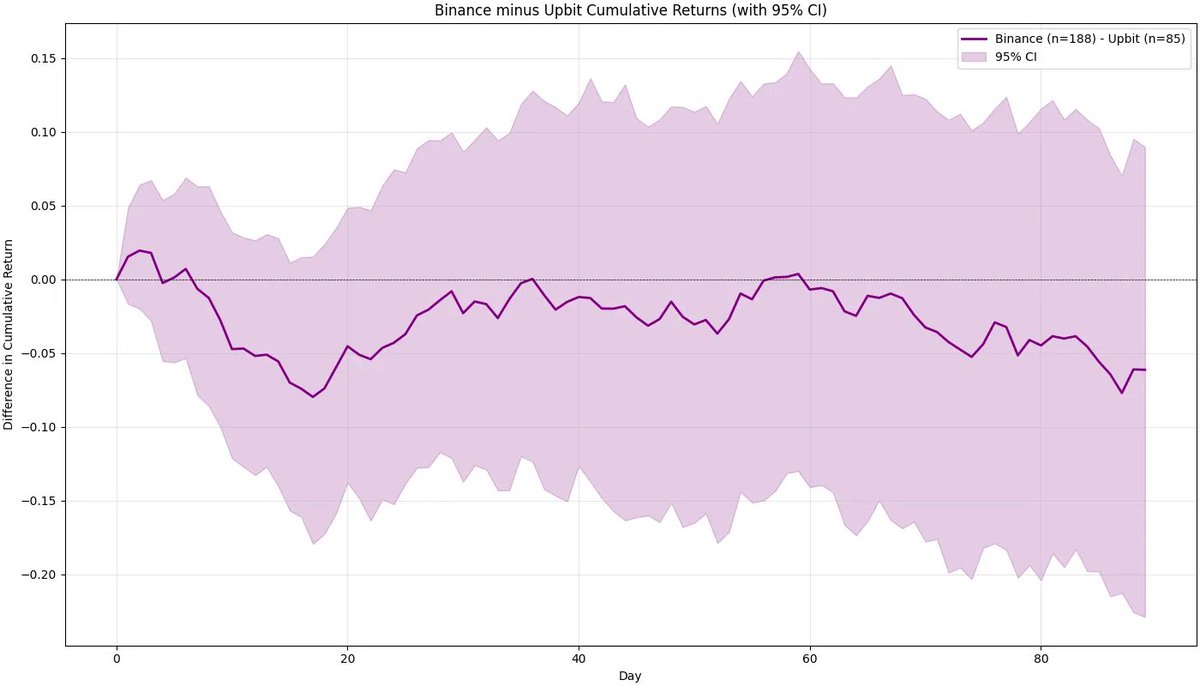

We can't directly answer this—there's no clear data yet. But you should at least have an estimate in mind, think through the logic, and come up with a number. I mentioned earlier that Upbit is also a "ultimate goal" exchange, and people love listing in Korea. Unfortunately, we still see strong post-listing selling pressure. For projects, this is almost always an endgame—maybe not as severe as Binance, but still significant—you can clearly see this in the data. The figure below shows Upbit’s performance and the difference between Binance and Upbit.

Ninety days later, Upbit performs slightly better than Binance, but the difference is so small that we can't reasonably claim Upbit is a superior listing venue. In both cases, we see strong selling pressure—which, upon reflection, is completely logical.

How to Price Liquidity?

One thing almost nobody considers.

After listing on Binance, liquidity far exceeds any other exchange. Binance allows founders and investors to partially exit positions as needed, or to make larger purchases when buying back (honestly, I wish this happened more often). So how should a project or investor value this significant increase in liquidity?

This is something (almost) only Binance can offer—and something every market participant should be willing to pay for, directly or indirectly.

We all desire deep liquidity and the ability to go long or short perpetual contracts (of course, our analysis here focuses on spot exchanges, not perpetuals, but it's worth mentioning as an important feature).

A Simple Test for Binance’s Liquidity Advantage

I’ve been thinking about a simple way to test whether Binance’s liquidity is truly superior to other exchanges while avoiding major bias. Here’s my idea:

-

Find tokens listed on Bybit and Coinbase.

-

Find tokens listed on Binance, but only after they’ve already been listed on Bybit and Coinbase (ideally with as long a time gap as possible).

-

Compare the liquidity on Binance, Bybit, and Coinbase a few days after the Binance listing.

In this setup, Bybit and Coinbase have mature markets, while Binance is an emerging one. If Binance still shows significantly better liquidity, we can confidently say the liquidity surplus from a Binance listing is real and substantial.

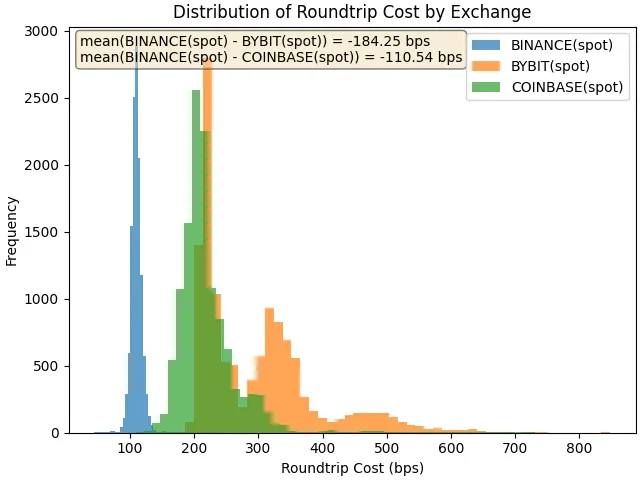

The chart shows the distribution of round-trip costs—the cost of executing a $100,000 market buy and a $100,000 market sell. Higher cost means lower liquidity. For token LA, which listed on Binance over a month after Bybit and Coinbase, we found that five days later, the round-trip cost on Binance was 184 basis points lower than on Bybit and 110 basis points lower than on Coinbase.

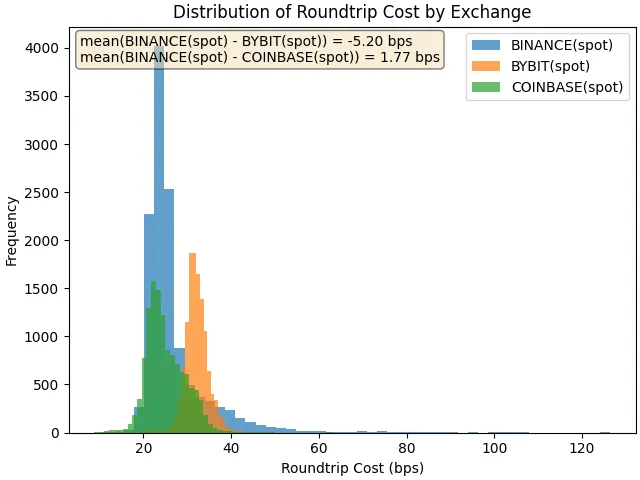

For ONDO, the round-trip cost between Binance and Coinbase is roughly similar—Coinbase has a slight edge (only 1.77 basis points, likely due to tick size differences).

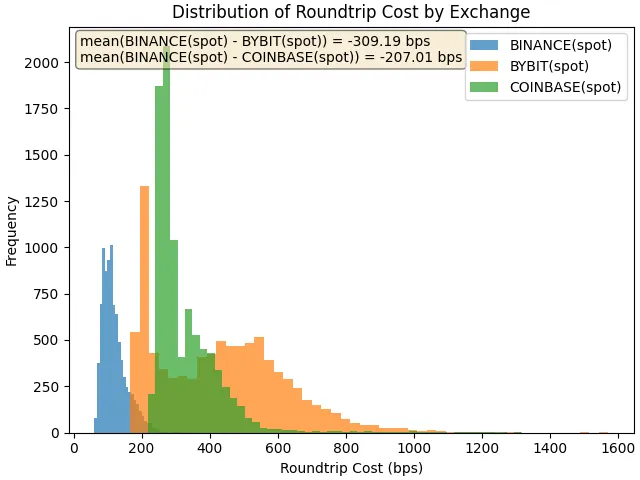

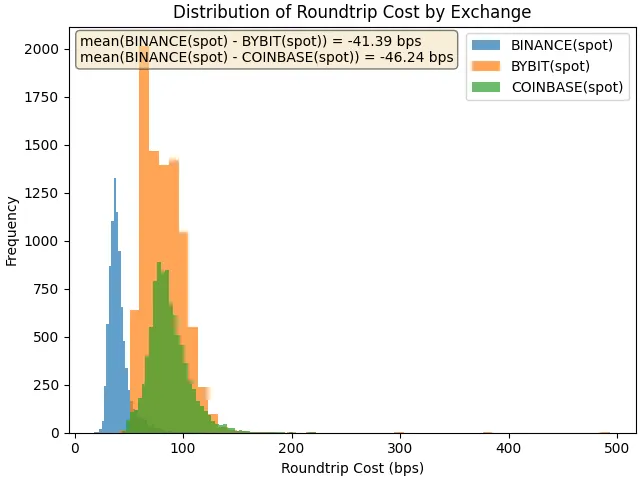

Now let’s look at the less liquid product AXL. Here, the cost difference is huge. For a $100,000 trade, the difference is 309 basis points versus Bybit and 207 basis points versus Coinbase. For a $20,000 trade, the difference remains 41 and 46 basis points respectively. From the perspective of any existing or potential holder, these numbers are staggering.

What’s Next?

This is clearly not the only way to research this topic—but it's a biased starting point. If we want to go deeper, here are some open questions (I won’t answer them now—time, as always, is limited):

-

How should we incorporate broader market trends and their relationship with listing performance?

-

How can we quantify the announcement effect and include it in our analysis?

-

How should we weigh individual cases? Is ONDO more important than AXL? If so, by what metric (perhaps market cap)?

-

Should we make our analysis more robust—for example, by winsorizing outliers?

-

Would excluding BSC tokens from Binance data significantly change the results?

We could keep asking such questions endlessly—that's the beauty of research.

There’s always room for improvement, but ultimately, creativity and research ethics matter more than any specific model. Conducting nearly unbiased research will take you further than any machine learning method. It’s always about your ideas, your data preparation, and your culture of reasoning.

Conclusion

We’re not here just to talk about research—we’re here to talk about Binance.

Whether you believe Binance is "evil" or "a cancer in the industry" is entirely up to you. Critically examine yourself. Don’t let bias and emotion hold you back. Because that’s not where profits are made.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News