Why was your position suddenly liquidated under extreme market conditions?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Why was your position suddenly liquidated under extreme market conditions?

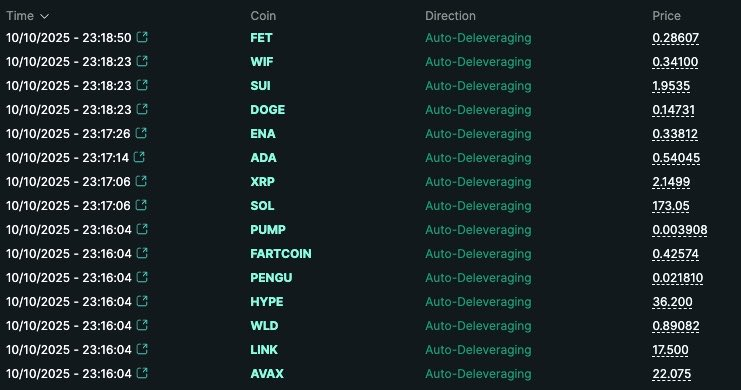

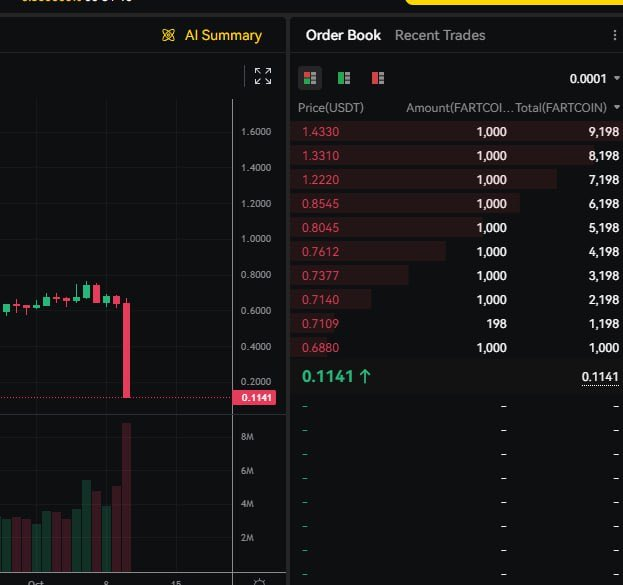

Cash games without BTC, where the automatic deleveraging mechanism kicks in when long-short imbalance occurs.

Author: Doug Colkitt

Translation: TechFlow

Given that many people woke up to find their perpetual positions liquidated and are wondering what "Auto-Deleveraging" (ADL) means, here's a concise beginner's guide.

What is ADL? How does it work? Why does it exist?

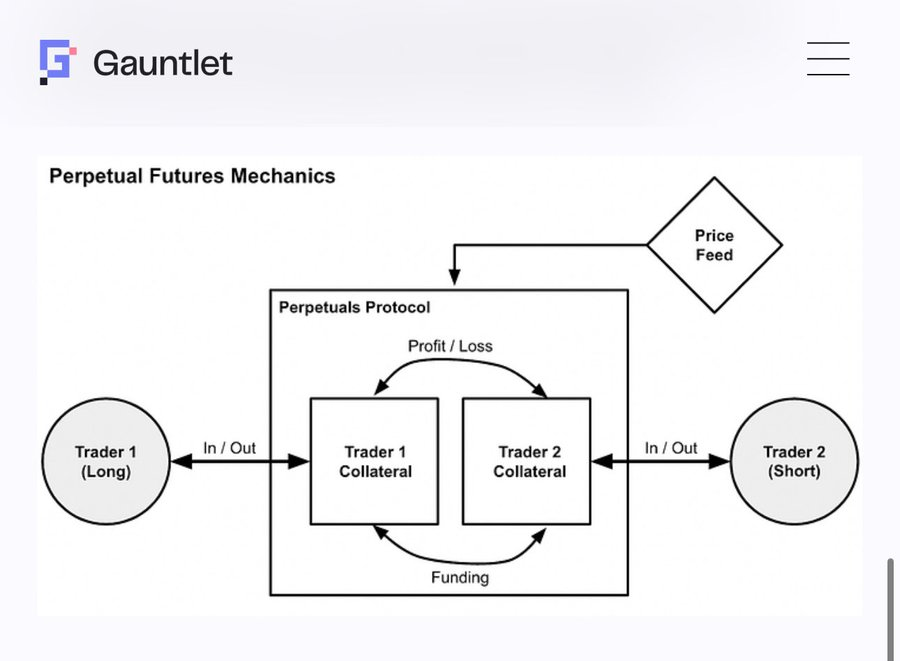

First, we need to understand at a higher level what a perpetual market is and what it does. Take the BTC perpetual market as an example—interestingly, there isn't actually any real BTC in this system. There's just a large pool of idle cash.

What the perpetual market (or more broadly, any derivatives market) does is redistribute this pile of cash among participants. It operates via a set of rules designed to create synthetic instruments that behave like BTC within a system that doesn't actually contain BTC.

The most important rule is: there are longs and shorts in the market, and long and short positions must be perfectly balanced, or the system cannot function. In addition, both longs and shorts must deposit cash (as margin) into this pool.

This pool of funds gets redistributed among participants as the price of BTC moves up and down.

During this process, when BTC price moves too drastically, some participants will lose all their funds. At that point, they are forcibly removed ("liquidated").

Remember, longs can only profit if there are shorts with funds left to lose (and vice versa). So when funds run out, you can no longer stay in the market.

Moreover, every short must be perfectly matched with a solvent long. If one long in the system has no funds left to lose, then by definition, the corresponding short also has no source of profit (and vice versa).

Therefore, if a long is liquidated, one of the following two things must happen in the system:

A) A new long enters the system, bringing fresh capital to replenish the pool;

B) The corresponding short position is closed, restoring balance to the system.

In ideal cases, this can all happen through normal market mechanisms. As long as willing buyers can be found at fair market prices, no one needs to be forced into action. In standard liquidations, this process typically occurs via the regular order book of the perpetual market.

In a healthy, liquid perpetual market, this works perfectly fine. The liquidated long position is sold into the order book, the best bid fills it, becoming the new long in the system and bringing in fresh capital to replenish the pool. Everyone is happy.

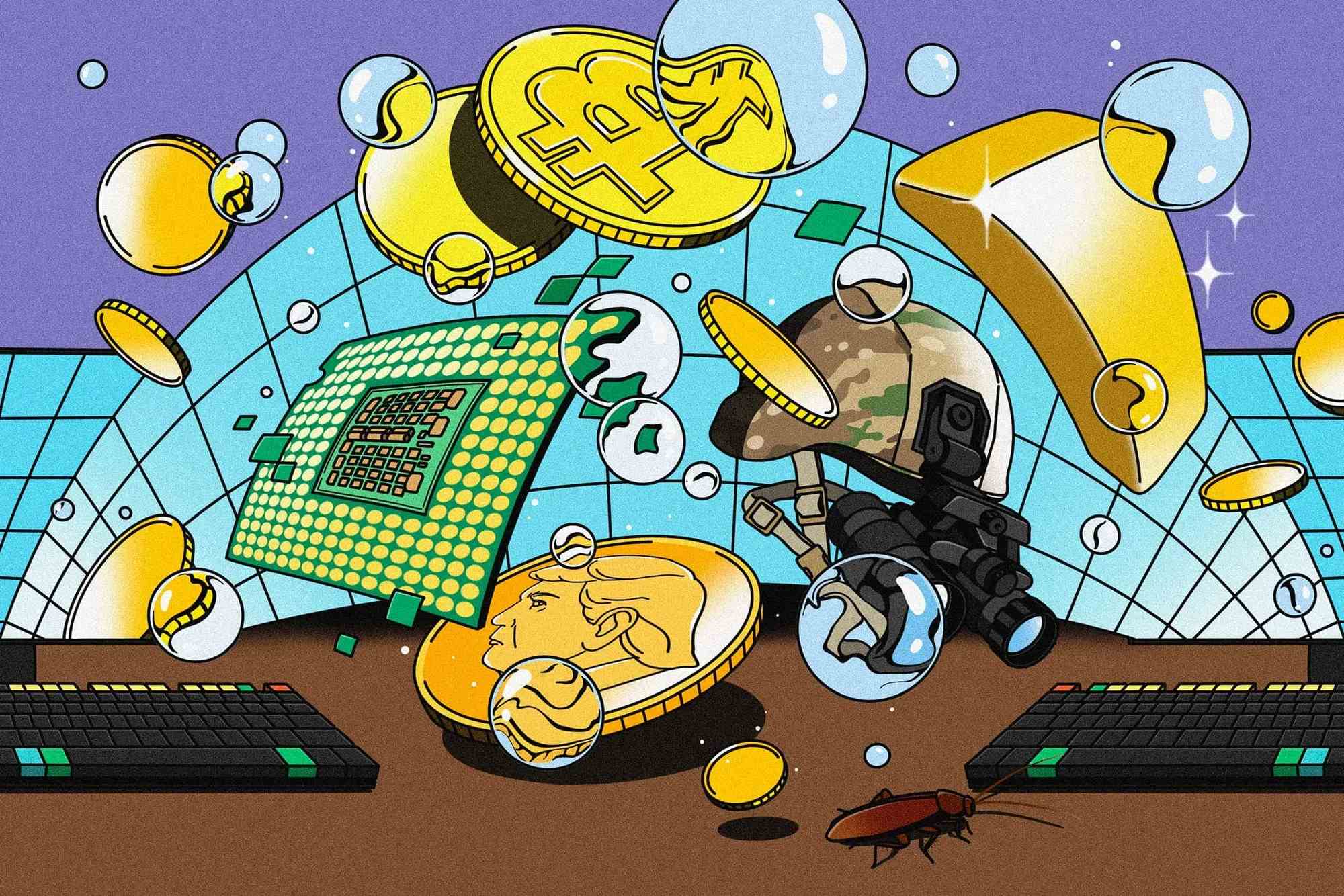

But sometimes, the order book lacks sufficient liquidity, or at least not enough to execute the trade without the original position losing more than its remaining equity.

This becomes a problem because it means there isn't enough cash in the pool to meet other participants' needs.

Typically, the next "rescue mechanism" involves an "insurance vault" or "insurance fund." This is a special pool backed by the exchange that steps in during extreme liquidity events, absorbing the other side of the liquidation.

The vault is often quite profitable over time because it can buy at steep discounts and sell at high prices during volatile moves. For instance, Hyperliquid’s vault earned about $40 million in a single hour tonight.

But the vault isn't magic—it's just another participant in the system. Like everyone else, it must deposit funds into the pool, follow the same rules, and its risk capacity and contributed capital are limited.

Therefore, the system must have a final "last resort" step.

This is what we call "Auto-Deleveraging" (ADL). It's a last resort—and a situation (hopefully) rarely encountered—because it involves forcing people out of their positions rather than paying them. It happens so infrequently that even experienced perpetual traders often barely notice it exists.

You can think of it like an overbooked flight. First, the airline uses market mechanisms to resolve the issue, such as increasing compensation to incentivize passengers to take a later flight. But if no one volunteers, some passengers must be forcibly removed.

If long-side funds are exhausted and no one is willing to step in and take their place, the system has no choice but to force at least some shorts to exit and close their positions. The processes different exchanges use to select which positions to close and at what prices vary widely.

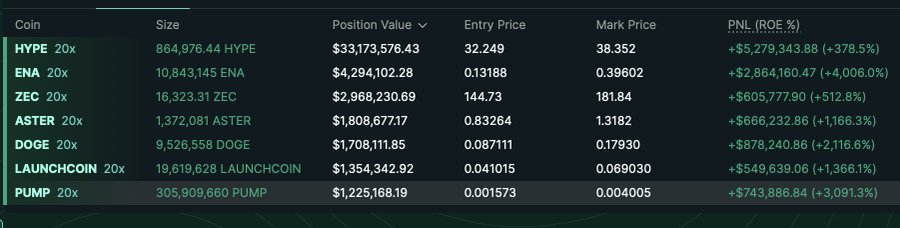

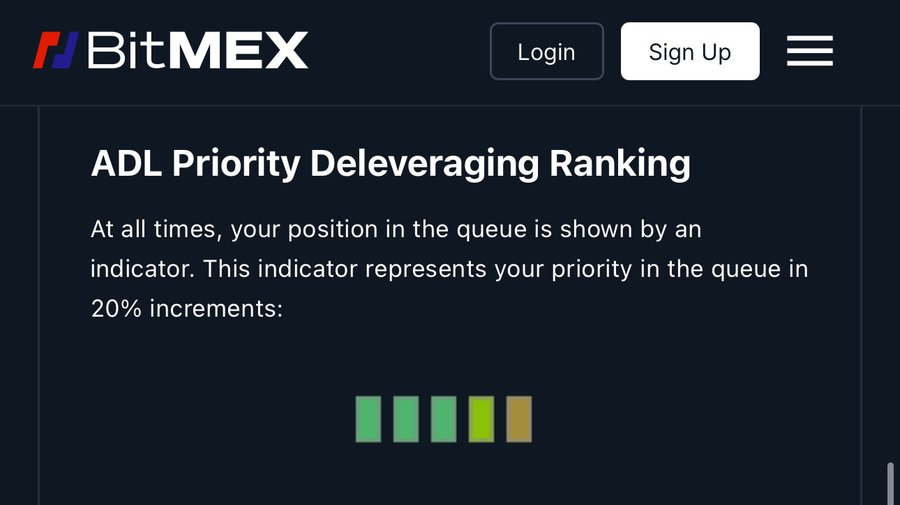

Typically, ADL systems use a ranking mechanism to select profitable positions for closure based on criteria such as: 1) highest profit; 2) leverage level; 3) position size. In other words, the largest, most profitable "whales" get sent home first.

Naturally, people feel upset about ADL because it seems unfair. You're riding a winning streak and suddenly get forced out. But to some extent, it's necessary. Even the best exchanges can't guarantee an infinite supply of losers to keep the pool funded.

You can think of it like a winning streak in Texas Hold'em. You enter the casino, beat everyone at the table, move to the next table, win again, then move to another. Eventually, everyone else runs out of chips. That's the essence of ADL.

The beauty of perpetual markets is that they are always zero-sum, so the system as a whole never becomes insolvent.

There isn't even real BTC that can devalue. Just a pile of boring cash. Like the laws of thermodynamics, value within the system is neither created nor destroyed.

ADL is a bit like the ending of the movie *The Truman Show*. Perpetual markets build a very convincing simulation that feels like a real world tied to the spot market.

But ultimately, it's all virtual. Most of the time, we don't need to think about this... but sometimes, we hit the edge of the simulation.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News