a16z's latest insight: Consumer-grade AI companies will redefine the enterprise software market

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

a16z's latest insight: Consumer-grade AI companies will redefine the enterprise software market

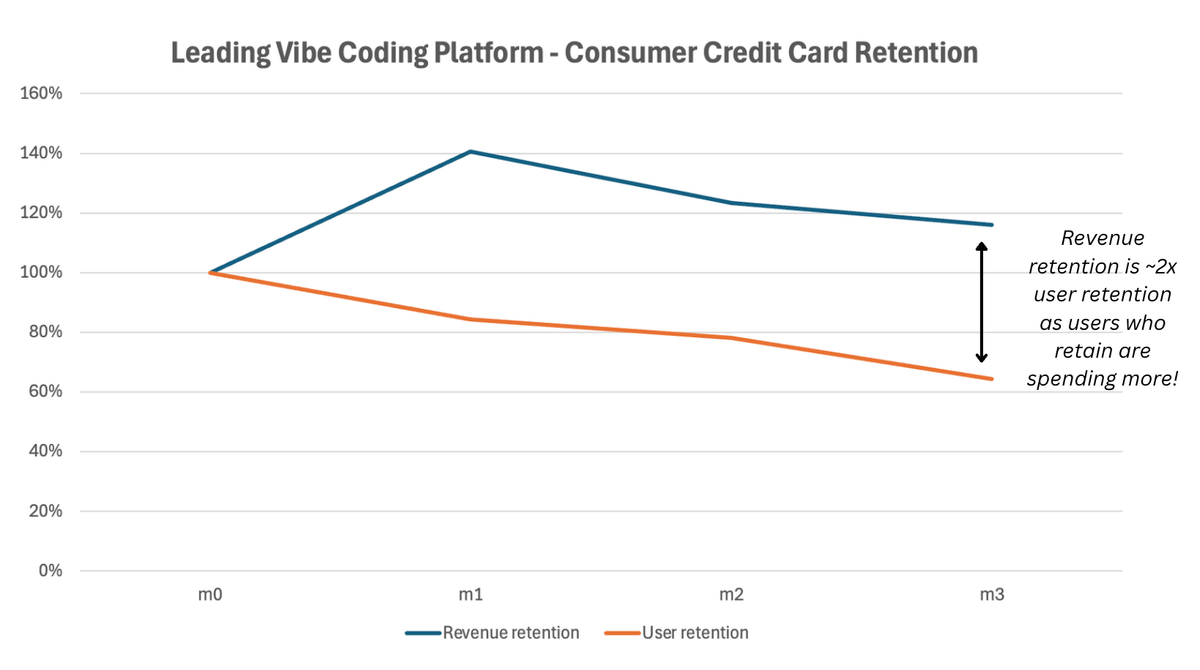

Consumer software companies no longer need to fight against user churn, but can instead rely on the continuous expansion of user value to achieve growth.

Have you ever wondered why AI consumer products that emerged in the past two years have been able to grow from zero to millions of users and surpass $100 million in annual revenue in less than two years? This pace of growth was nearly unimaginable before AI. On the surface, it’s because distribution is faster and average user revenue is higher. But I’ve noticed a deeper shift that most people have overlooked: AI has fundamentally transformed the revenue retention model for consumer software.

Recently, I read an analysis by a16z partner Olivia Moore titled “The Great Expansion: A New Era of Consumer Software,” where she refers to this phenomenon as the "Great Expansion." I believe she has identified a crucial trend. After reflecting deeply on her argument, I realize this isn’t just a business model adjustment—it represents a fundamental change in the rules of the entire consumer software industry. We are witnessing a historic turning point: consumer software companies no longer need to fight against user churn but can instead grow by continuously expanding user value. The boundary between consumer and enterprise markets is gradually blurring.

This shift has massive implications. Traditional consumer software companies used to spend enormous effort and capital every year replacing lost users—just to maintain the status quo. Now, companies leveraging AI find that their user cohorts not only retain value but actually generate more revenue over time. It’s like shifting from a leaky bucket to an inflating balloon—the growth model is entirely different.

From this perspective, I personally believe this presents a huge opportunity for global expansion, because consumer products can now leverage PLG (Product-Led Growth) to drive both growth and revenue, effectively bypassing the common weakness of Chinese teams in overseas SLG (Sales-Led Growth). Even though these are enterprise-facing offerings, their growth mechanics resemble those of consumer products. I speak from personal experience—my own project, a B2B vibe coding product targeting enterprises, has been live for a month and achieved strong data feedback through PLG-driven customer acquisition.

The Fundamental Flaw in Traditional Models

Let’s first revisit how consumer software made money before AI. Moore identifies two primary models in her analysis, which I find accurate. The first is the ad-driven model, commonly used by social apps, directly tied to usage volume, resulting in relatively flat per-user value over time. Instagram, TikTok, and Snapchat are representative examples. The second is single-tier subscription models, where all paying users pay the same fixed monthly or annual fee for access. Duolingo, Calm, and YouTube Premium follow this approach.

In both models, revenue retention is almost always below 100%. A certain percentage of users churn each year, while remaining users continue paying the same amount. For consumer subscription products, maintaining 30–40% user and revenue retention at the end of the first year is considered “best practice.” These numbers sound bleak.

I’ve always felt there’s a structural flaw in this model: it creates a fundamental constraint where companies must constantly replace lost revenue just to maintain growth, let alone expand. Imagine having a leaky bucket—you must pour water in faster than it leaks just to raise the water level. That’s the dilemma traditional consumer software companies face: trapped in an endless cycle of acquiring users, losing them, and then re-acquiring them.

The problem isn’t just numerical—it affects overall company strategy and resource allocation. Most energy goes toward acquiring new users to offset churn, rather than deepening relationships with existing users or enhancing product value. This explains why so many consumer apps aggressively push notifications or use various tactics to boost engagement—they know revenue vanishes the moment users stop using the product.

I believe this model fundamentally underestimates the potential value of users. It assumes user value is fixed—once they subscribe, their revenue contribution caps out. But in reality, as users become more familiar with a product, their needs often grow, and so does their willingness to pay. The traditional model fails to capture this upward value trajectory.

AI Rewrites the Rules of the Game

AI has completely changed this dynamic. Moore calls this shift the “Great Expansion,” a name I find very fitting. The fastest-growing consumer AI companies now report revenue retention rates exceeding 100%—something nearly inconceivable in traditional consumer software. This happens in two ways: first, consumer spending increases as usage-based pricing replaces fixed “access” fees; second, consumers bring tools into the workplace at unprecedented speed, where they can be reimbursed and supported by larger budgets.

A key behavioral shift I’ve observed is the fundamental change in user engagement patterns. In traditional software, users either use the product or don’t; they’re either subscribed or canceled. But with AI products, user engagement and value contribution grow progressively. They might start by occasionally using basic features, but as they recognize the AI’s value, they become increasingly dependent, and their needs expand.

The divergence in trajectories is dramatic. As Moore notes, at 50% revenue retention, a company must replace half its user base annually just to stay flat. At over 100%, each user cohort expands, with growth compounding on itself. This isn’t just a marginal improvement—it represents an entirely new growth engine.

I believe several deep factors drive this change. AI products exhibit a learning effect—they become more valuable with use. The more time and data users invest, the greater the product’s value to them. This creates a positive feedback loop: increased usage leads to greater value, which drives further usage and higher willingness to pay.

Another critical factor is the practical nature of AI products. Unlike many traditional consumer apps, AI tools often directly solve specific user problems or enhance productivity. This makes the benefits tangible, increasing users’ willingness to pay. When an AI tool saves you hours of work, paying for additional usage feels entirely justified.

Smart Pricing Architecture Design

Let me dive deeper into how the most successful consumer AI companies structure their pricing. Moore points out that these companies no longer rely on a single subscription fee but instead use hybrid models combining multiple subscription tiers with usage-based components. If users exhaust their included credits, they can purchase more or upgrade to a higher plan.

I see an important lesson here from the gaming industry. Game companies have long derived most of their revenue from high-spending “whales.” Limiting pricing to one or two tiers likely leaves significant revenue on the table. Smart companies build tiers around variables like number of generations or tasks, speed and priority, or access to specific models, while also offering credit packs and upgrade paths.

Consider some concrete examples. Google AI offers a $20/month Pro subscription and a $249/month Ultra plan, charging extra fees for Veo3 credits when users inevitably exceed their included amounts. Additional credit packs range from $25 to $200. From what I understand, many users end up spending as much on extra Veo credits as on the base subscription. This perfectly illustrates how revenue can scale with user engagement.

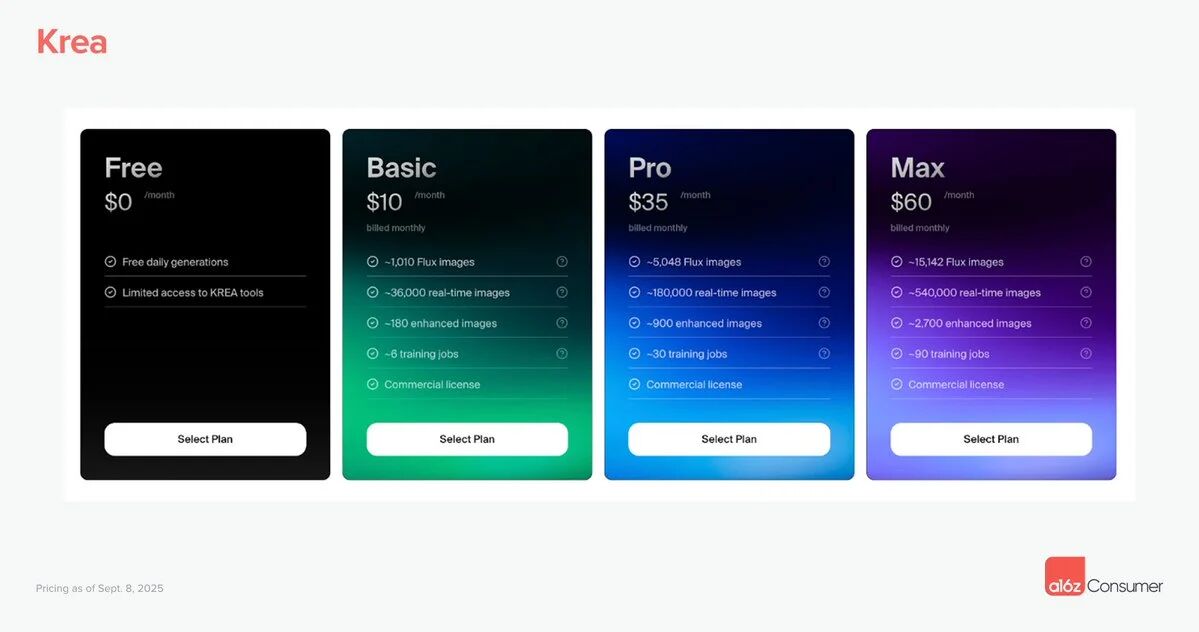

Krea’s model is also interesting, offering plans from $10 to $60 per month based on expected usage and training jobs, with optional add-on credit packs priced from $5 to $40 (valid for 90 days) if users exceed their compute units. The elegance of this model lies in providing affordable entry points for light users while allowing heavy users room to scale.

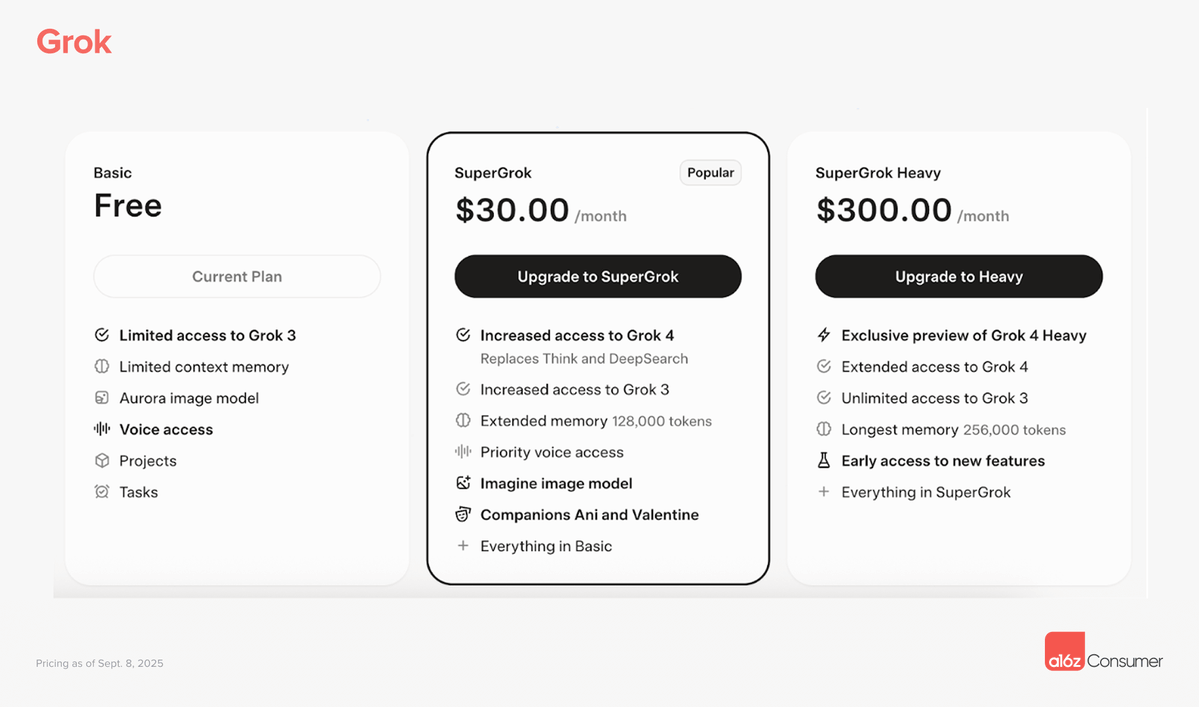

Grok takes this strategy even further: SuperGrok costs $30/month, while SuperGrok Heavy is $300/month, unlocking new models (Grok 4 Heavy), expanded model access, longer memory, and early feature testing. A 10x price difference like this would be unthinkable in traditional consumer software, but in the AI era, it makes sense due to vast differences in user needs and perceived value.

I believe the success of these models stems from recognizing the diversity and dynamism of user value. Not all users have the same needs or spending power, and individual needs evolve over time. By offering flexible pricing options, these companies capture the full spectrum of user value.

Moore mentions that some consumer companies achieve over 100% revenue retention purely through such pricing models—even before any enterprise expansion. This underscores the power of the approach. It doesn’t just solve the churn problem of traditional consumer software—it creates an intrinsic growth mechanism.

The Golden Bridge from Consumer to Enterprise

Another major trend I’ve observed is the unprecedented speed at which consumers bring AI tools into the workplace. Moore emphasizes this point: employees are actively rewarded for introducing AI tools at work. In some companies, failing to become “AI-native” is now seen as unacceptable. Any product with potential work applications—essentially anything that isn’t NSFW—should assume users will want to bring it into their teams, and they’ll pay significantly more when expenses are reimbursable.

The speed of this shift impresses me. In the past, transitioning from consumer to enterprise typically took years, requiring extensive market education and sales efforts. But AI tools are so clearly useful that users spontaneously introduce them into their work environments. I’ve seen numerous cases where employees first buy an AI tool personally, then convince their company to purchase the enterprise version for the whole team.

The shift from price-sensitive consumers to price-insensitive enterprise buyers creates massive expansion potential. But this requires core collaboration features like team folders, shared libraries, collaborative canvases, authentication, and security. I believe these features are now essential for any consumer AI product with enterprise potential.

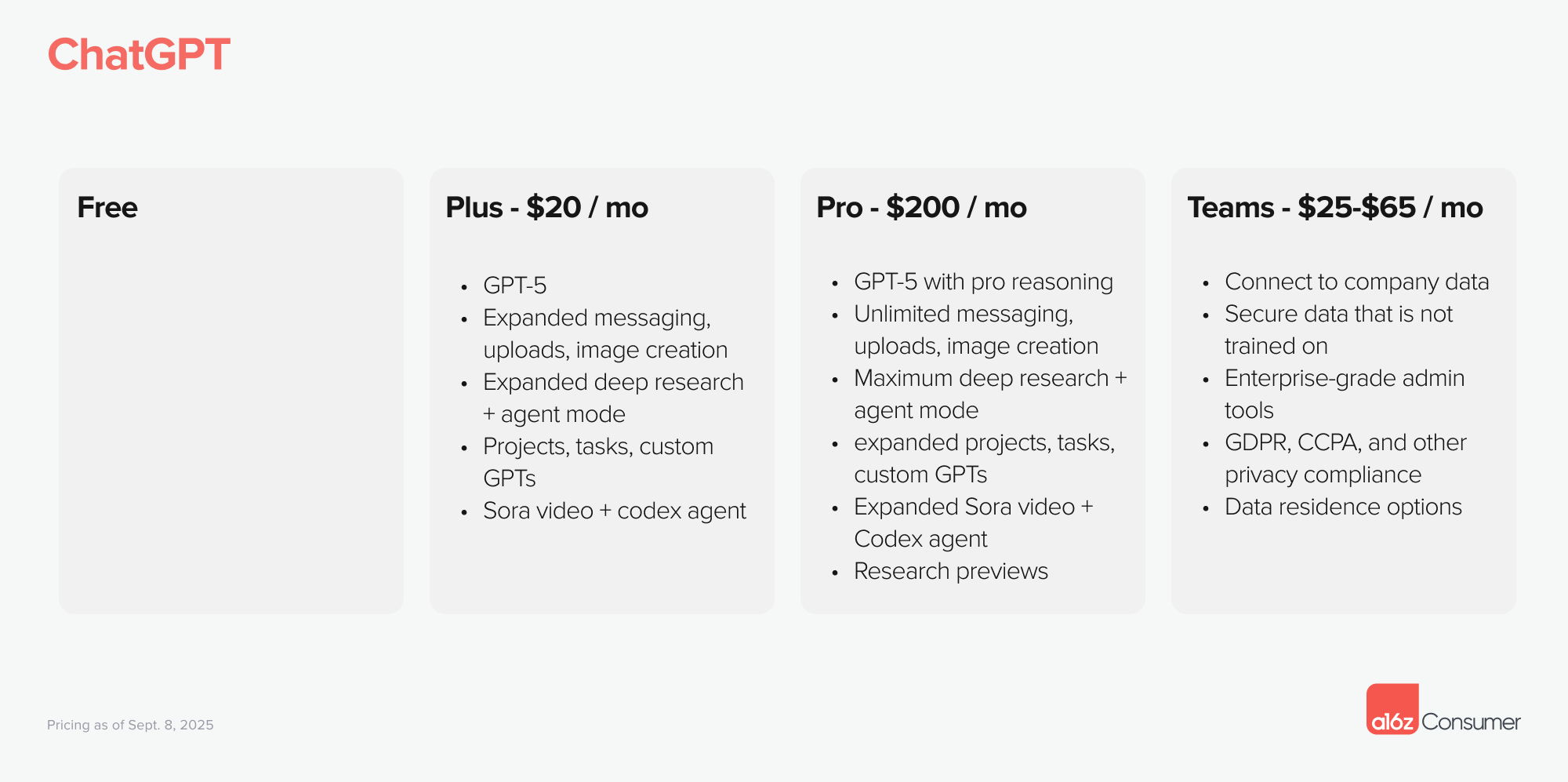

With these capabilities in place, pricing differences can be substantial. ChatGPT is a good example—even though it’s not widely seen as a team product, its pricing highlights the gap: $20/month for individuals versus enterprise plans ranging from $25 to $60 per user. Such 2–3x price differences were rare in traditional consumer software but are becoming common in the AI era.

I think some companies even price individual plans at break-even or slight loss to accelerate team adoption. Notion effectively used this strategy in 2020, offering unlimited free pages to individual users while charging heavily for collaboration features, driving its most explosive growth phase. The logic is clear: subsidize individual usage to build a user base, then monetize through enterprise features.

Take Gamma, for instance: its Plus plan is $8/month to remove watermarks—a requirement for most enterprise use—plus other features. Then users pay for each collaborator added to their workspace. This model cleverly leverages enterprise demand for professional presentation.

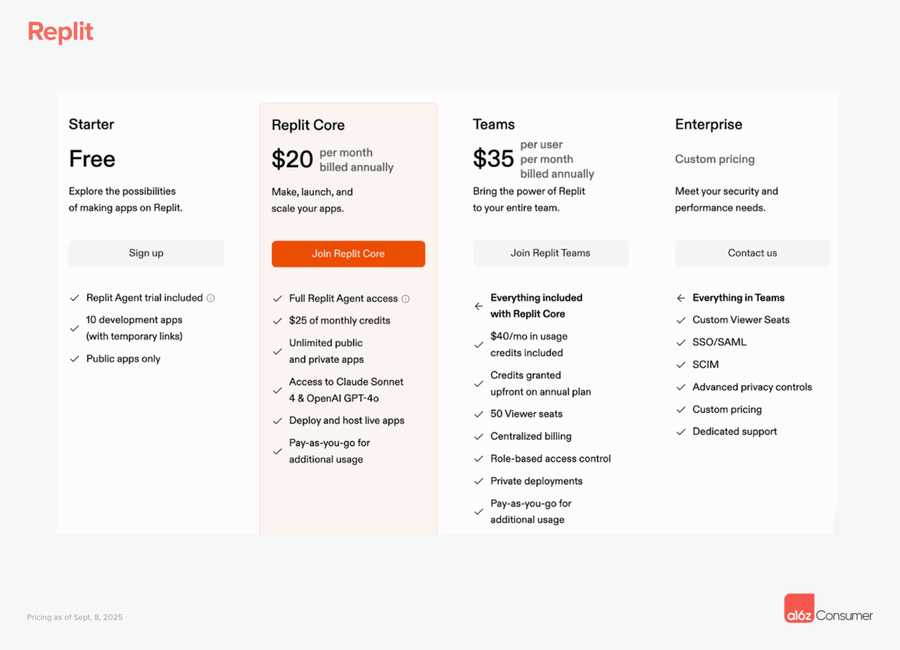

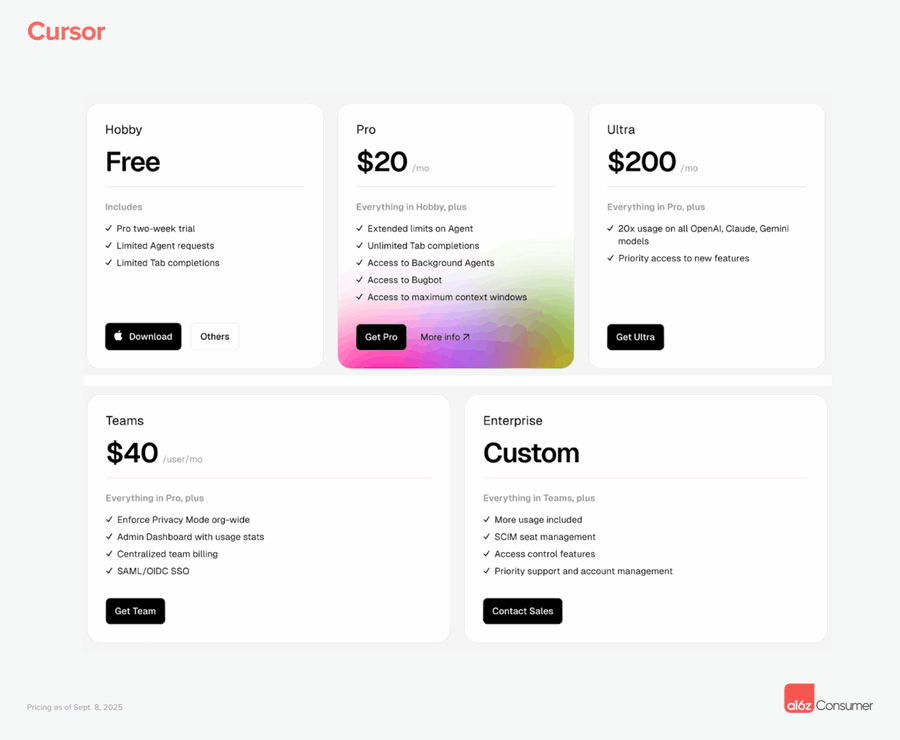

Replit offers a $20/month plan for Core users. Team plans start at $35/month, including extra credits, viewer seats, centralized billing, role-based access control, private deployments, and more. Cursor offers a $20/month Pro plan and a $200/month Ultra plan (with 20x usage increase). Team users pay $40/month for Pro, with organization-wide privacy modes, usage and management dashboards, centralized billing, and SAML/SSO.

These features matter because they unlock enterprise-level ARPU (Average Revenue Per User) expansion. I believe any consumer AI company today that isn’t planning for enterprise expansion is missing a huge opportunity. Enterprise users not only pay more but are also typically more stable and have lower churn.

Invest in Enterprise Capabilities from Day One

Moore offers a seemingly counterintuitive yet highly insightful suggestion: consumer companies should consider hiring a sales lead within one to two years of founding. I fully agree, even though this contradicts traditional consumer product strategies.

Individual adoption can only take a product so far; ensuring widespread organizational adoption requires navigating enterprise procurement and closing high-value contracts. This demands professional sales expertise—not just relying on organic product spread. I’ve seen too many excellent consumer AI products miss big opportunities due to lack of enterprise sales capability.

Canva, founded in 2013, waited nearly seven years before launching its Teams product. Moore notes that in 2025, such delays are no longer viable. The pace of enterprise AI adoption means that if you delay enterprise features, competitors will seize the opportunity. Competitive pressure is vastly accelerated in the AI era, as market changes happen faster than ever.

I believe several key features often determine success. For security and privacy: SOC-2 compliance, SSO/SAML support. For operations and billing: role-based access control, centralized billing. For product: team templates, shared themes, collaborative workflows. These may sound basic, but they’re often decisive in enterprise purchasing decisions.

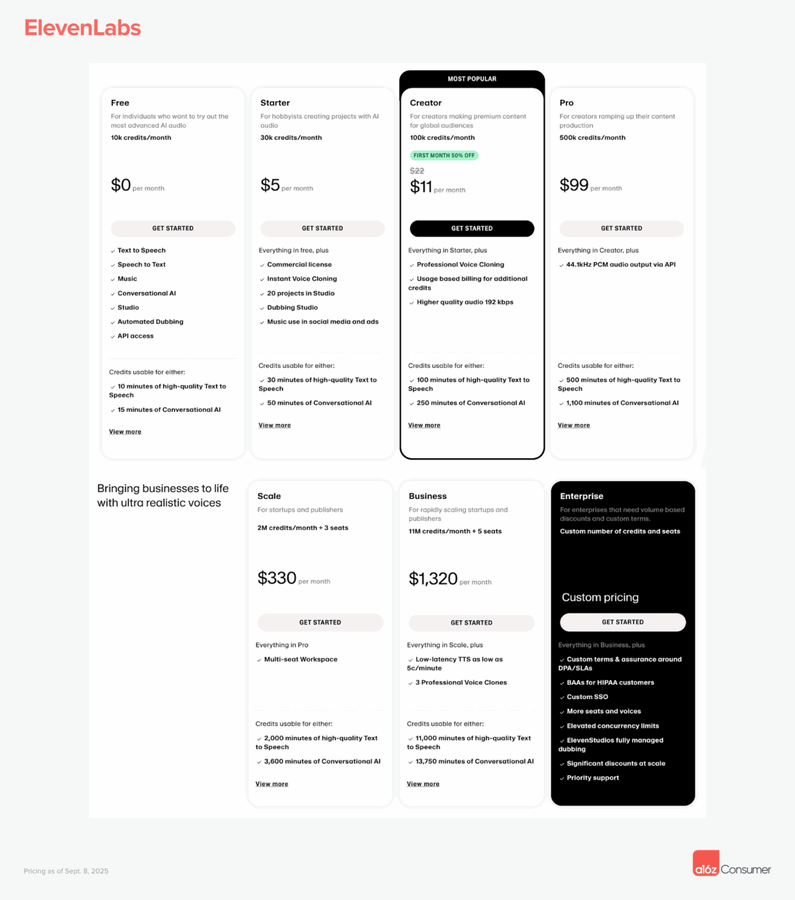

ElevenLabs is a great example: starting heavily focused on consumers, the company quickly built enterprise-grade capabilities, adding HIPAA compliance for its voice and conversation agents and positioning itself to serve healthcare and other regulated industries. This rapid enterprise transformation allowed them to capture high-value clients beyond consumer revenue.

I’ve observed an interesting pattern: consumer AI companies that invest early in enterprise capabilities often build stronger moats. Once enterprise customers adopt a tool and integrate it into workflows, switching costs become high. This leads to stronger customer stickiness and more predictable revenue streams.

Additionally, enterprise customers provide valuable product feedback. Their needs are often more complex, pushing the product toward more advanced development. I’ve seen many consumer AI products discover new directions and feature requirements through serving enterprise clients.

My Deep Reflections on This Transformation

After carefully analyzing Moore’s insights and my own observations, I believe we’re witnessing not just a business model tweak but a fundamental restructuring of the software industry’s infrastructure. AI hasn’t just changed what products can do—it has transformed how value is created and captured.

What fascinates me most is how this shift challenges traditional assumptions about consumer software. For years, consumer software was assumed to be inherently low-priced, high-churn, and hard to monetize. But the reality of the AI era shows that consumer software can achieve enterprise-scale revenue and growth. The implications are profound.

From a capital allocation standpoint, this means investors can now deploy more capital earlier into consumer AI companies, as they can reach meaningful revenue scales faster. Traditionally, consumer software companies had to wait until achieving massive user scale before effective monetization. Now, strong revenue growth is possible even with relatively small user bases.

I’ve also reflected on how this impacts startup strategy. Moore notes that many of the most important companies of the AI era may have started as consumer products. I find this insight deeply perceptive. The traditional B2B startup path usually involves extensive market research, customer interviews, and long sales cycles. Starting with a consumer approach enables faster product iteration and market validation.

Another advantage of this path is that it fosters more natural product-market fit. When consumers voluntarily use and pay for a product, it signals strong product-market alignment. Then, when they bring it into their workplaces, enterprise adoption becomes more organic and sustainable.

I’ve also noticed an interesting shift in competitive dynamics. In the traditional software era, consumer and enterprise markets were largely separate, with different players and strategies. But in the AI era, the boundaries blur. A single product can compete in both markets simultaneously, creating new advantages and challenges.

Technically, I believe the dual nature of AI products—consumer-friendly usability plus enterprise-grade functionality—is raising new standards in product design and development. Products must be simple enough for individual users to pick up easily, yet powerful and secure enough to meet enterprise demands. Achieving this balance isn’t easy, but those who do gain significant competitive advantages.

I’ve also considered the impact on established enterprise software companies. Traditional enterprise vendors now face competition from AI-first consumer-originated companies that often offer better UX and faster iteration. This could force the entire enterprise software industry to elevate its product standards and user experience.

Finally, I believe this shift reflects a fundamental change in how we work. Remote work, increased individual autonomy in tool selection, and higher expectations for productivity tools are all blurring the lines between consumer and enterprise tools. AI is simply accelerating a trend already underway.

Future Opportunities and Challenges

While I’m excited about the “Great Expansion” phenomenon Moore describes, I also see important challenges and opportunities ahead.

On the challenge side, competition will intensify. When a successful path becomes clear, more companies will attempt to replicate it. Those who can establish strong differentiation and network effects will win in the long run.

From a regulatory perspective, the rapid adoption of AI tools in enterprise settings may trigger new compliance and security concerns. Companies must ensure their AI tools meet various industry standards and regulations. This could increase development costs and complexity, but it may also create new competitive barriers.

On the opportunity side, I see vast space for innovation. Companies that creatively combine consumer ease-of-use with enterprise functionality will open new market categories. I also believe vertical-specific AI tools hold great promise—deep optimization for particular industries or use cases may prove more valuable than general-purpose tools.

I also see opportunities in data and AI model network effects. As user numbers grow and usage deepens, AI products can become smarter and more personalized. This data-driven improvement can create powerful competitive advantages, as newcomers struggle to replicate accumulated intelligence.

From an investment standpoint, I believe this trend will continue attracting significant capital. But investors will need to be smarter in identifying companies with truly sustainable competitive advantages, not just short-term growth leaders. The key will be recognizing which companies can build real moats, not just capitalize on early market momentum.

In the end, I believe Moore’s “Great Expansion” is only the beginning of the AI revolution. We are redefining the essence of software—from tools to intelligent partners, from features to outcomes. Companies that grasp and execute on this transformation will build the next generation of tech giants. This isn’t just business model innovation—it’s a reimagining of the relationship between humans and technology. We are in an exciting era where software is becoming smarter, more useful, and more indispensable than ever.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News