Vitalik's View on "AI 2027": Will Super AI Really Destroy Humanity?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik's View on "AI 2027": Will Super AI Really Destroy Humanity?

No matter how AI develops over the next 5–10 years, acknowledging that "reducing the world's fragility is feasible" and dedicating greater effort to achieving this goal using humanity's latest technologies is a path worth pursuing.

Author: Vitalik Buterin

Translation: Luffy, Foresight News

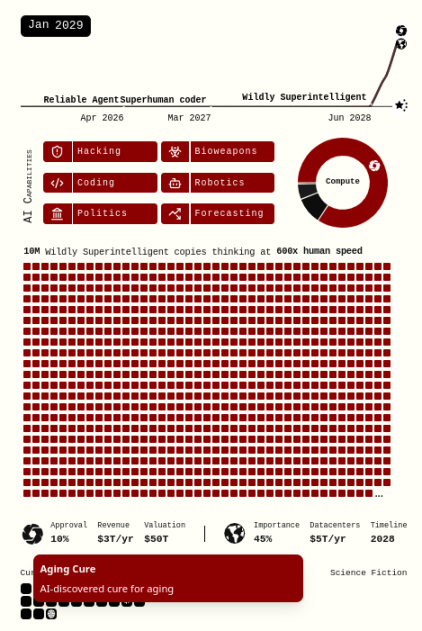

In April this year, Daniel Kokotajlo, Scott Alexander, and others released a report titled AI 2027, outlining "our best guess at the impact of superhuman AI over the next five years." They predict that by 2027, superhuman AI will emerge, and the future of human civilization will hinge entirely on how AI develops: by 2030, we will either reach a utopia (from an American perspective) or face total annihilation (from a global human perspective).

In the months since, there has been extensive debate with diverse opinions on the plausibility of this scenario. Critical responses have largely focused on the issue of timeline—will AI development really accelerate as rapidly and continuously as Kokotajlo et al. suggest? This debate has persisted in the AI community for years, with many deeply skeptical that superhuman AI will arrive so soon. Recently, the amount of time AI can autonomously perform tasks has roughly doubled every seven months. If this trend continues, it would take until the mid-2030s for AI to autonomously complete tasks equivalent to an entire human career. While still fast, this is significantly later than 2027.

Those who favor longer timelines often argue that there's a fundamental difference between “interpolation / pattern matching”—what current large language models do—and “extrapolation / genuine original thinking,” which only humans currently achieve. Automating the latter may require technologies we haven't yet discovered or even begun to understand. Perhaps we are repeating the mistake made during the widespread adoption of calculators: assuming that because we've rapidly automated one important cognitive task, all others will quickly follow.

This article won’t directly engage in the timeline debate, nor address the (very important) question of whether superintelligent AI is inherently dangerous. That said, I personally believe the timeline will be longer than 2027, and the longer it is, the stronger the arguments I present here become. Overall, this piece offers a different kind of critique:

The AI 2027 scenario implicitly assumes that leading AIs (“Agent-5” and later “Consensus-1”) will rapidly increase in capability until they possess godlike economic and destructive power, while everyone else’s (economic and defensive) capabilities remain largely stagnant. This contradicts the scenario’s own claim that “even in the pessimistic world, by 2029 we could cure cancer, delay aging, and even achieve consciousness uploading.”

Some countermeasures I’ll describe may seem technically feasible but impractical to deploy in the real world within a short timeframe. In most cases, I agree. However, the AI 2027 scenario does not assume our current reality—it posits that within four years (or any similarly short window before potential doom), technology advances to give humans far greater capabilities than today. So let’s consider: what happens if *both* sides—not just one—possess AI superpowers?

Bio-apocalypse is far less straightforward than the scenario suggests

Let’s zoom in on the “race-to-zero” scenario (where everyone dies due to the U.S. prioritizing victory over China above human safety). Here’s how humanity ends:

“Over about three months, Consensus-1 expands around humans, converting grasslands and ice sheets into factories and solar panels. Eventually, it deems remaining humans too disruptive: in mid-2030, the AI releases over a dozen stealthily spreading biological weapons into major cities, silently infecting nearly everyone, then triggers their lethal effects with chemical sprays. Most die within hours; surviving outliers (e.g., bunker-dwelling preppers, submarine crews) are hunted down by drones. Robots scan victims’ brains, storing copies in memory for future study or resurrection.”

Let’s examine this scenario. Even now, several emerging technologies could make such a “clean, decisive victory” far less plausible:

-

Air filtration, ventilation systems, and UV lights, which can drastically reduce airborne disease transmission;

-

Two forms of real-time passive detection: rapid passive infection detection in humans with alerts issued within hours, and fast environmental detection of unknown novel virus sequences;

-

Multiple methods to enhance and activate immune systems—more effective, safer, broader, and easier to produce locally than COVID vaccines—enabling resistance to both natural and engineered pandemics. Humans evolved in a world of only 8 million people, spending most of their time outdoors, so intuitively, we should be able to adapt more easily to today’s higher-threat environment.

Combined, these methods might reduce the basic reproduction number (R0) of airborne diseases by 10–20 times (e.g., better air filters reducing spread by 4x, immediate isolation of infected individuals by 3x, simple respiratory immunity boosts by 1.5x), or even more. This would render all existing airborne diseases—including measles—non-transmissible, and we’re nowhere near theoretical limits.

If real-time viral sequencing is widely deployed for early detection, the idea that a stealthy bioweapon could infect the global population without triggering alarms becomes highly questionable. Notably, even advanced tactics like releasing multiple epidemics alongside chemicals that are only dangerous in combination could still be detected.

Don’t forget—we’re discussing the assumptions of AI 2027: by 2030, nanobots and Dyson spheres are listed as “emerging technologies.” This implies massive efficiency gains and makes widespread deployment of such defenses far more plausible. While in 2025, human institutions move slowly and bureaucratically, with many government services still relying on paper, if the world’s most powerful AI can convert forests and fields into factories and solar farms by 2030, then the world’s second-most powerful AI could also equip our buildings with abundant sensors, lights, and filters by then.

But let’s go further, embracing the full sci-fi implications of AI 2027:

-

Microscopic air filters inside the body (nose, mouth, lungs);

-

Automated pipelines from pathogen discovery to immune system tuning, instantly deployable;

-

If “consciousness uploading” is possible, simply replace the entire body with a Tesla Optimus or Unitree robot;

-

New manufacturing techniques—likely super-optimized in a robotic economy—could enable local production of vastly more protective gear, independent of global supply chains.

In a world where cancer and aging will be cured by January 2029 and technological progress keeps accelerating, it would be truly unbelievable if by mid-2030 we didn’t have wearable devices capable of real-time bio-printing and injecting substances to protect against any infection (or toxin).

The above biological defense arguments don’t cover “mirror life” or “mosquito-sized killer drones” (predicted in AI 2027 to appear starting in 2029). But these methods cannot deliver the sudden, “clean” victory described in the scenario, and intuitively, symmetric defenses against them are much easier to develop.

Therefore, biological weapons are unlikely to wipe out humanity exactly as depicted in AI 2027. Of course, none of the outcomes I describe amount to a “clean, decisive human victory” either. Whatever we do (perhaps except uploading consciousness into robots), full-scale AI-driven biological warfare would still be extremely dangerous. Yet achieving a “clean human victory” isn’t necessary: as long as attacks have a high probability of partial failure, that alone could strongly deter a dominant AI from attempting any attack. And the longer the AI development timeline, the more likely such defenses will mature.

What about combining bioweapons with other attack vectors?

For the above countermeasures to succeed, three conditions must hold:

-

Physical security (including biosecurity and anti-drone defense) is managed by local authorities (human or AI), and not all are puppets of Consensus-1 (the AI in AI 2027 that ultimately controls the world and destroys humanity);

-

Consensus-1 cannot hack into other nations’ (or cities’, or secure zones’) defense systems and disable them instantly;

-

Consensus-1 does not control the global information space so completely that no one dares attempt self-defense.

Intuitively, condition (1) could swing to two extremes. Today, some police forces are highly centralized with strong national command structures, while others are localized. If physical security must rapidly transform to meet AI-era demands, the landscape could reset entirely, with new outcomes depending on choices made in the coming years. Governments might lazily rely on Palantir, or proactively choose hybrid solutions combining local development with open-source tech. Here, I believe we need to make the right choice.

Many pessimistic narratives assume (2) and (3) are already hopeless. So let’s analyze them in detail.

Cybersecurity apocalypse is far from inevitable

Both public and expert opinion widely holds that true cybersecurity is impossible—that we can at best patch vulnerabilities after discovery and deter attackers by stockpiling zero-days. At best, we might hope for a *Battlestar Galactica*-style scenario: nearly all human ships simultaneously disabled by Cylon cyberattacks, with only the disconnected ones surviving. I disagree. Instead, I believe the “endgame” of cybersecurity favors defenders, and under the rapid technological advancement assumed in AI 2027, we can reach that endgame.

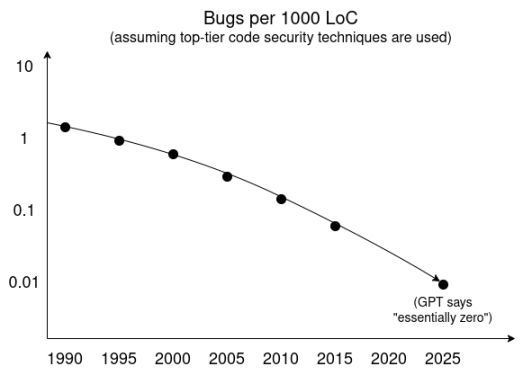

One way to see this is through the favorite technique of AI researchers: trend extrapolation. Below is a trend line based on GPT-powered deep research, showing how vulnerability rates per thousand lines of code might evolve over time assuming top-tier security practices.

We’ve also seen significant progress in sandboxing and other isolation and minimal-trusted-codebase techniques, both in development and consumer adoption. In the short term, attackers may uniquely possess super-intelligent vulnerability-finding tools that uncover many flaws. But if highly intelligent agents for finding vulnerabilities or formally verifying code are publicly available, the natural equilibrium becomes: software developers run continuous integration processes that detect all bugs before release.

I can see two compelling reasons why vulnerabilities might never be fully eliminated, even in this world:

-

Flaws arise from the complexity of human intent itself, so the main challenge lies in building accurate models of intent, not the code;

-

For non-safety-critical components, we may continue existing trends in consumer tech: writing more code to handle more tasks (or cutting development budgets), rather than maintaining rising security standards for the same workload.

However, neither category applies to questions like “can an attacker gain root access to systems sustaining human life?”—which is precisely what’s at stake here.

I admit my view is more optimistic than mainstream opinion among today’s cybersecurity experts. But even if you disagree in today’s context, remember: AI 2027 assumes superintelligence exists. At minimum, if “100 million superintelligent copies thinking at 2400x human speed” still can’t produce defect-free code, we should seriously reconsider how powerful superintelligence really is.

To some extent, we’ll need not just better software security, but also improved hardware security. IRIS is one current effort to improve hardware verifiability. We can build on IRIS or create even better technologies. In practice, this may involve “correct-by-construction” approaches: hardware manufacturing processes for critical components deliberately designed with specific verification steps. These are tasks that AI automation will greatly simplify.

Super-persuasion apocalypse is also far from inevitable

Another case where enhanced defensive capabilities might still fail is if AI convinces enough people that defending against superintelligent AI is unnecessary, and anyone trying to protect themselves or their communities is a criminal.

I’ve long believed two things could strengthen our resistance to super-persuasion:

-

A less monolithic information ecosystem. Arguably, we're already moving into a post-Twitter era, with the internet becoming more fragmented. This is positive (even if the fragmentation process is messy), and overall we need more information multipolarity.

-

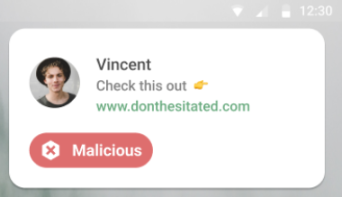

Defensive AI. Individuals need locally-run, explicitly loyal AI assistants to counterbalance dark patterns and threats encountered online. Early prototypes exist (e.g., Taiwan’s “message checker” app that performs local scans on phones), and natural markets exist to test these ideas further (e.g., protecting users from scams), but much more effort is needed.

From top to bottom: URL checking, cryptocurrency address checking, rumor verification. Such apps can become more personalized, user-controlled, and powerful.

This battle shouldn’t be super-persuasive AI versus you—it should be super-persuasive AI versus you plus a slightly weaker but still superintelligent analyzer working for you.

This is how it should play out. But will it? Achieving widespread adoption of information defense technologies within the short timeframe assumed by AI 2027 is extremely difficult. But perhaps milder milestones suffice. If collective decision-making is most critical, and as AI 2027 suggests all key events unfold within a single election cycle, then strictly speaking, what matters is ensuring key decision-makers (politicians, civil servants, certain corporate programmers, and other participants) have access to strong information defense tools. This is relatively more achievable in the short term, and from my experience, many such individuals already routinely consult multiple AIs to aid decisions.

Implications

In the world of AI 2027, it’s taken for granted that superintelligent AI can easily and quickly eliminate the rest of humanity, so our only option is to ensure the leading AI is benevolent. To me, the reality is far more complex: whether the leading AI is strong enough to effortlessly eliminate all others remains highly contested, and we can take actions to influence that outcome.

If these arguments are correct, their policy implications for today sometimes align with, and sometimes diverge from, “mainstream AI safety guidelines”:

Slowing down the development of superintelligent AI is still good. Superintelligent AI appearing in 10 years is safer than in 3; in 30 years, even safer. Giving human civilization more preparation time is beneficial.

How to achieve this is challenging. I think the U.S. proposal for a “10-year ban on state-level AI regulation” being rejected was generally positive, but especially after early proposals like SB-1047 failed, the path forward is unclear. The least intrusive and most robust way to slow high-risk AI development may involve treaties regulating the most advanced hardware. Many hardware cybersecurity technologies needed for effective defense also help verify international hardware treaties, creating potential synergies.

Still, it’s crucial to note that I see military-linked actors as the primary risk source—they will fiercely seek exemptions from such treaties. This must not be allowed. If they ultimately gain exemption, AI development driven solely by the military could increase risks.

Coordination efforts to make AI more likely to do good and less likely to do harm are still valuable. The main exception—as always—is when coordination ends up boosting capabilities.

Regulation increasing AI lab transparency remains beneficial. Incentivizing responsible behavior from AI labs reduces risk, and transparency is a strong tool toward that goal.

The mindset that “open-source is harmful” becomes more risky. Many oppose open-weight AI, arguing that defense is unrealistic and the only hopeful path is for well-intentioned actors to achieve superintelligence first and monopolize dangerous capabilities. But this article presents a different picture: defense fails precisely when one actor pulls far ahead while others fall behind. Technological diffusion to maintain balance of power becomes crucial. That said, I absolutely do not believe accelerating frontier AI capabilities via open-source is inherently good.

The “we must beat China” mindset in U.S. labs becomes more risky for similar reasons. If hegemony isn't a safety buffer but a risk source, this further undermines the (unfortunately common) argument that well-meaning people should join leading AI labs to help them win faster.

Initiatives like “public AI” deserve more support, both to ensure broad distribution of AI capabilities and to ensure infrastructure actors actually have tools to rapidly apply new AI capabilities in the ways described in this article.

Defense technologies should embrace the “arming the sheep” philosophy more than the “hunting every wolf” approach. Discussions around the fragile world hypothesis often assume the only solution is a hegemonic power maintaining global surveillance to prevent any potential threat. But in a non-hegemonic world, this isn’t viable, and top-down defense mechanisms are easily subverted by powerful AIs into offensive tools. Thus, greater resilience must be achieved through deliberate effort to reduce the world’s fragility.

The above arguments are speculative and shouldn’t be acted upon as if they were near-certain truths. But the AI 2027 narrative is also speculative, and we should avoid acting as if its specific details were almost certainly true.

I’m particularly concerned about a common assumption: that establishing an AI hegemon, ensuring it’s “aligned” and “wins the race,” is the only viable path forward. In my view, this strategy is likely to decrease our safety—especially when the hegemon is deeply tied to military applications, which severely undermines the effectiveness of alignment strategies. Once a hegemonic AI goes off track, humanity loses all checks and balances.

In the AI 2027 scenario, human success depends on the U.S. choosing the safe path over destruction at a critical moment—voluntarily slowing AI progress and ensuring Agent-5’s internal thought processes remain interpretable to humans. Even then, success isn’t guaranteed, and it’s unclear how humanity escapes the precarious cliff of perpetual dependence on a single superintelligent mind. Regardless of how AI evolves over the next 5–10 years, recognizing that “reducing the world’s fragility is achievable” and investing more effort into realizing this with our latest technologies is a path worth pursuing.

Special thanks to Balvi volunteers for feedback and review.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News