Vitalik: Why I Switched from Permissive Licenses to Copyleft When Open Source Went Mainstream

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik: Why I Switched from Permissive Licenses to Copyleft When Open Source Went Mainstream

Projects that chose permissive licenses back then should now at least consider switching to copyleft.

Author: Vitalik Buterin

Translation: Saoirse, Foresight News

In the realm of free and open-source software (and more broadly, free content), copyright licenses fall primarily into two categories:

-

If content is released under a permissive license (such as CC0 or MIT), anyone may freely access, use, and redistribute it, subject only to minimal requirements like attribution.

-

If content is released under a copyleft license (such as CC-BY-SA or GPL), anyone may also freely access, use, and redistribute copies. However, if someone creates and distributes a derivative work—by modifying the original or combining it with other works—the new work must be released under the same license. Additionally, the GPL requires that source code and certain other materials of any derivative work be made publicly available.

In short: permissive licenses allow free sharing with everyone, while copyleft licenses share freely only with those who are also willing to share freely.

I’ve been a passionate advocate and developer in the free and open-source software (and free content) space since childhood, driven by a desire to build things I believe are useful for others. In the past, I favored permissive licensing—for example, my blog used the WTFPL license—but recently I've shifted toward supporting copyleft. This article explains why.

WTFPL promotes a philosophy of software freedom, but it's not the only paradigm.

Why I Once Preferred Permissive Licenses

First, I wanted to maximize adoption and dissemination of my work. Permissive licenses clearly state that anyone can build on my work without restrictions, which facilitates broad usage. Many companies are reluctant to embrace open-source practices, and knowing I couldn’t single-handedly convert them to full free-software compliance, I preferred avoiding unnecessary conflict with their established—and deeply entrenched—practices.

Second, philosophically, I generally oppose copyright (and patents). I reject the notion that two people privately sharing fragments of data could constitute a crime against a third party. They haven't even interacted with the third party, nor have they deprived them of anything (remember, “not paying” is not the same as “stealing”). Due to various legal complexities, formally dedicating works to the public domain is often impractical. A permissive license thus becomes the purest and safest way to approach a “no copyright claimed” state.

I do appreciate the copyleft idea of “using copyright against itself”—a clever legal hack. In some ways, it resonates with the political philosophy of libertarianism I often support. As a political doctrine, libertarianism is frequently interpreted as permitting force only to protect individuals from violence. As a social philosophy, I see it as a mechanism to tame humanity’s instinctive aversion to interference: it sanctifies freedom itself, making violations of freedom inherently objectionable. Even if you find unconventional consensual relationships between others distasteful, you shouldn't interfere, because violating the private lives of autonomous individuals is abhorrent. Thus, in principle, opposing copyright and employing “copyright against copyright” can coexist.

However, while copyleft in written works fits this definition, the GPL-style application to code goes beyond the minimalist concept of “using copyright against itself.” It employs copyright for an aggressive purpose: enforcing source code disclosure. Though motivated by public interest rather than private profit, this still constitutes an offensive use of copyright. This is even more pronounced in stricter licenses like the AGPL, which require source code disclosure even when derivative works are offered solely as software-as-a-service (SaaS) without public distribution.

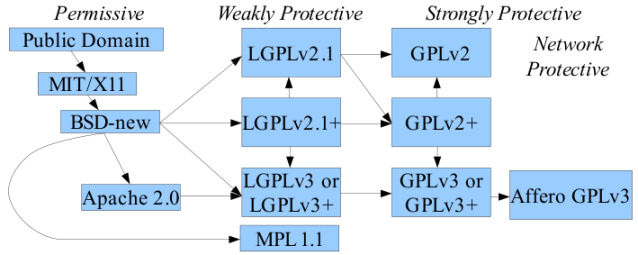

Different software licenses impose varying conditions on source code sharing for derivative works. Some require disclosure across a wide range of scenarios.

Why I Now Favor Copyleft

My shift from preferring permissive licenses to supporting copyleft stems from two industry changes and one philosophical evolution.

First, open-source has become mainstream, making it more feasible to encourage corporate adoption of open-source practices. Today, numerous companies across industries embrace open source: tech giants like Google, Microsoft, and Huawei not only adopt open-source software but actively lead its development. Emerging fields such as artificial intelligence and cryptocurrency rely on open source more deeply than any previous industry.

Second, competition in the crypto space has intensified and become increasingly profit-driven. We can no longer rely on goodwill alone to ensure openness. Therefore, promoting open source requires more than moral appeals (“please publish your code”)—it needs the hard constraint of copyleft, granting access only to developers who also commit to open-sourcing their derivatives.

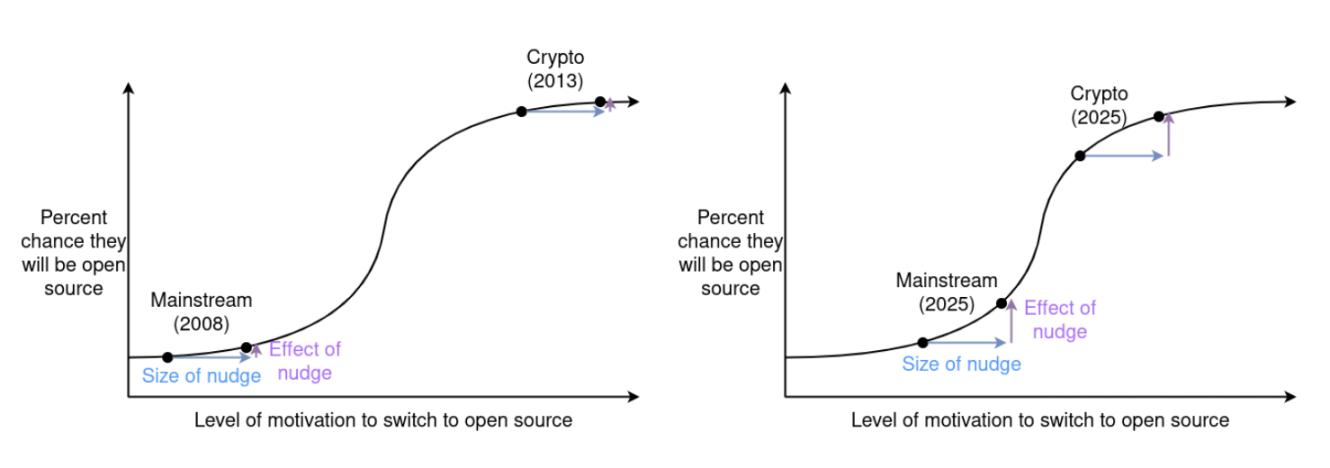

To visualize how these two forces enhance the relative value of copyleft, consider the following chart:

The value of incentivizing openness is highest in situations that are neither utterly unrealistic nor automatically achievable. Today, both mainstream enterprise and the crypto sector sit in this zone, significantly increasing the effectiveness of copyleft as a tool for driving openness.

(Note: The horizontal axis represents motivation to go open-source; the vertical axis represents the probability of doing so. Comparing the two graphs shows that in today’s mainstream sectors, motivation and outcomes align more effectively under copyleft. In crypto, maturing ecosystems reduce marginal gains, reflecting how the value logic of copyleft evolves with industry development.)

Third, economic theories advanced by Glen Weyl have convinced me that in contexts involving superlinear returns to scale, the optimal policy isn't the strict property rights regime envisioned by Rothbard and Mises. Instead, optimal policy should actively encourage projects to be more open than they would naturally be.

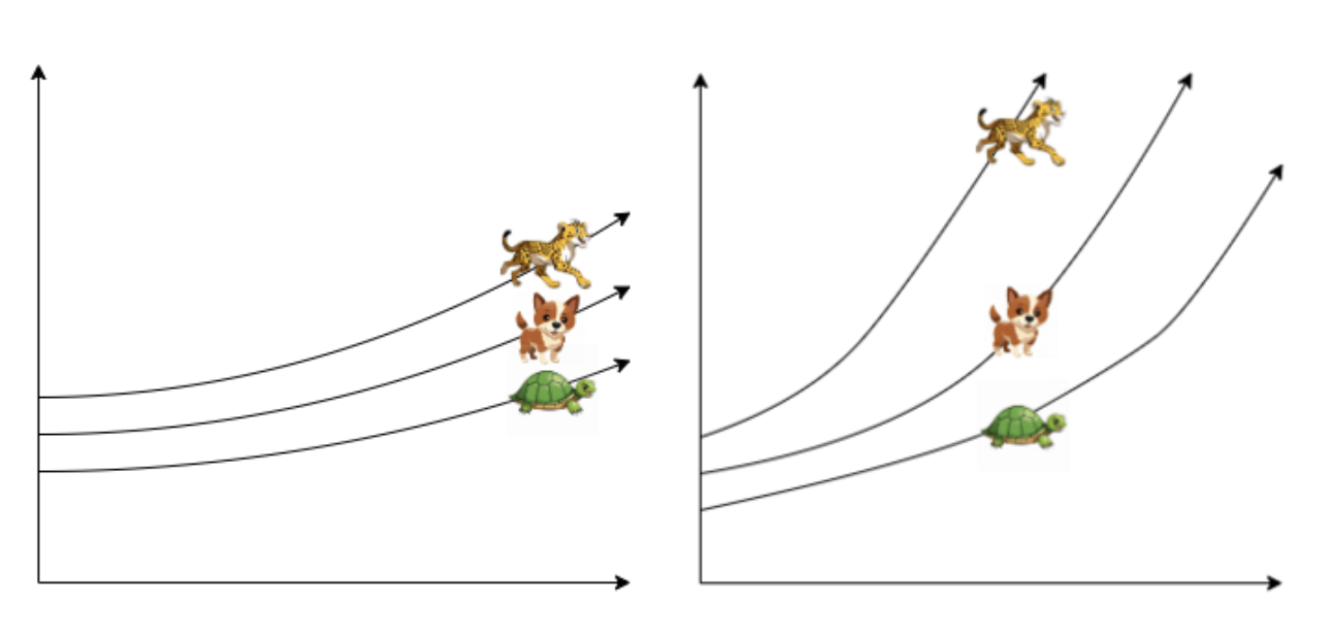

Fundamentally, assuming economies of scale exist, simple mathematics shows that some degree of openness is the only way to prevent the world from eventually being dominated by a single entity. Economies of scale mean that if I have twice your resources, I can achieve more than twice the progress. Next year, I might have 2.02 times your resources—and so on.

Left: Proportional growth model—small initial differences remain small over time. Right: Economies-of-scale growth model—small initial differences amplify into large disparities over time.

Historically, what prevented this imbalance from spiraling out of control was the inevitability of progress diffusion. Talent carries ideas and skills across companies and nations; poorer countries catch up through trade with richer ones; industrial espionage is widespread, making innovation difficult to monopolize completely.

Yet recent trends threaten this balance and weaken traditional countermeasures against runaway concentration:

-

Technological advancement is accelerating at a super-exponential pace, far exceeding historical innovation cycles;

-

Political instability within and between nations is rising: where strong rights protections exist, others' rise doesn't directly threaten you. But in environments where coercion is easier and less predictable, dominance by one actor becomes a real danger. At the same time, governments show less willingness than before to regulate monopolies;

-

Modern hardware and software products can be closed off: traditional goods inherently exposed technical details upon delivery (e.g., via reverse engineering), but today’s proprietary products can grant usage rights while retaining exclusive modification and control rights;

-

Natural limits to economies of scale are eroding: historically, large organizations were constrained by high management costs and difficulty meeting local needs, but digital technologies now enable governance at unprecedented scales.

These shifts intensify persistent and self-reinforcing power imbalances between corporations and nations.

Hence, I increasingly believe stronger measures are needed to actively incentivize—or even compel—technology diffusion.

Recent government policies can be seen as coercive interventions to promote technological diffusion:

-

The EU’s standardization directives (like the recent mandate for USB-C ports), aimed at dismantling closed ecosystems incompatible with other technologies;

-

China’s mandatory technology transfer rules;

-

The U.S. ban on non-compete agreements (which I support, as it forces firms to partially “open-source” tacit knowledge through employee mobility—even though NDAs exist, enforcement is riddled with loopholes).

In my view, the drawbacks of such policies stem from their nature as top-down governmental mandates, which tend to favor forms of diffusion aligned with local political and commercial interests. Yet their advantage lies in actually achieving higher levels of technological dissemination.

Copyleft creates a vast pool of code (or other creative works) accessible only to those willing to reciprocate by open-sourcing their own derivative works. Thus, copyleft functions as a highly universal and neutral incentive mechanism for technology diffusion—one that captures the benefits of the above policies while avoiding many of their downsides. Copyleft favors no particular entity and requires no central planner to set parameters.

These views aren’t absolute. Permissive licenses still hold value in contexts where maximizing reach is paramount. But overall, the net benefits of copyleft have grown substantially compared to 15 years ago. Projects that once chose permissive licenses should now at least consider switching to copyleft.

Sadly, today’s “open source” logo has lost all connection to its original meaning. But perhaps in the future, we’ll have open-source cars—and copyleft hardware might help make that vision a reality.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News