What Hidden "Ambitions" Does Anthropic Have Behind Claude Code?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

What Hidden "Ambitions" Does Anthropic Have Behind Claude Code?

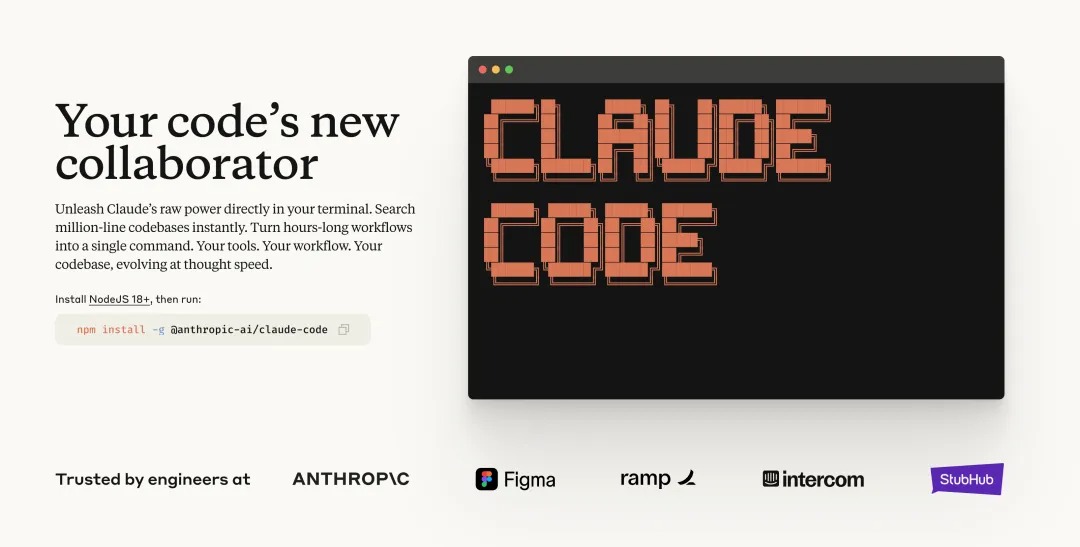

If you're still hesitating about trying Claude Code, don't think of it as learning a new tool—think of it as experiencing the possibility of collaborating with a super intelligent assistant.

By Leo, Shen Si Quan

Have you ever considered that while everyone is debating when AI will reach superintelligence, we might have already missed the most obvious signal? Recently, I've been deeply researching Agentic coding—specifically this new asynchronous form of coding—and extensively using products like Claude Code, Gemini CLI, and Ampcode. A few days ago, I published an article titled "After Cursor, Devin, and Claude Code, Another Dark Horse in AI Coding Is Rapidly Emerging." Many people probably didn’t realize that with the emergence of agentic coding tools like Claude Code, even Cursor now faces disruption.

After deep reflection, I’ve arrived at a bold hypothesis: we’ve been interpreting it through the wrong framework. Everyone sees it as a “better programming tool,” but the more I use it, the more convinced I am—it’s not a programming tool at all. It’s a general-purpose AI agent disguised as a terminal interface. Coincidentally, over the weekend I watched the latest interview with Michael Gerstenhaber, product lead at Anthropic. In it, he revealed that changes in AI models over the past year have been “dramatic”—that today’s models are “completely different” from those of a year ago—and that this pace is accelerating.

When Michael mentioned their AI agent working autonomously for seven hours on complex programming tasks, or that 30% of their entire codebase is now AI-generated, I realized a fact we may have overlooked: superintelligence might not arrive in the way we expect. It won’t announce itself dramatically. Instead, it will quietly integrate into our daily workflows, making us believe it’s just a “better tool.” Claude Code is exactly such an example—it’s packaged as a coding assistant, but what it actually demonstrates is the capability of a general-purpose AI agent. And upon deeper examination of Anthropic’s entire product ecosystem, I suspect this strategy of “gentle infiltration” is far more deliberate than we imagined. That’s why I’m writing this piece—to combine insights from Michael’s interview with my own hands-on experience and reflections, hoping to offer some meaningful perspectives.

The Hidden Acceleration of AI Evolution

Michael Gerstenhaber’s timeline shared in the interview made me realize we may be severely underestimating the speed of AI development. He said: “From Claude 3 to 3.5 first version took six months, then another six months to 3.5 second version, then another six months to 3.7—but only two months to reach Claude 4.” This isn’t linear improvement; it’s exponential acceleration. More importantly, he expects this change to become “faster, faster, and faster.”

This acceleration translates into qualitative leaps in real-world applications. Back in June last year, AI coding meant pressing Tab to autocomplete a line. By August, it could write entire functions. Now, you can assign a Jira task to Claude and let it work autonomously for seven hours, delivering high-quality code. This rate of evolution makes me question whether our expectations about “when superintelligence will arrive” are fundamentally flawed. We’re waiting for a breakthrough announcement, but superintelligence may already be weaving itself subtly into our everyday work.

What’s even more interesting is why programming has become such a key benchmark for AI progress. Michael offered a compelling explanation: it’s not just because models perform well at coding, but also because “engineers enjoy building tools for other engineers—and themselves—and they can assess output quality effectively.” This creates a rapid feedback loop for iteration. But programming’s significance also lies in its ubiquity—nearly every modern company has a CTO and software engineering team, and domain experts across fields—from medical research to investment banking—write Python scripts.

This leads to a deeper question: when AI achieves human-level—or even superhuman—performance in such a foundational and widespread skill, can we still understand it through the traditional lens of “specialized tools”? My experience with Claude Code tells me no. The capabilities it exhibits go far beyond coding—they reflect a general intelligence capable of understanding complex intentions, formulating detailed plans, and coordinating multiple tasks.

I’ve noticed Anthropic’s strategy here is remarkably clever. By packaging a general AI agent as a seemingly specialized coding tool, they avoid triggering panic or excessive hype, while allowing users to gradually adapt to collaborating with superintelligence in a relatively safe environment. This incremental introduction may be the ideal path for society to accept and integrate superintelligence.

Rethinking the Essence of Claude Code

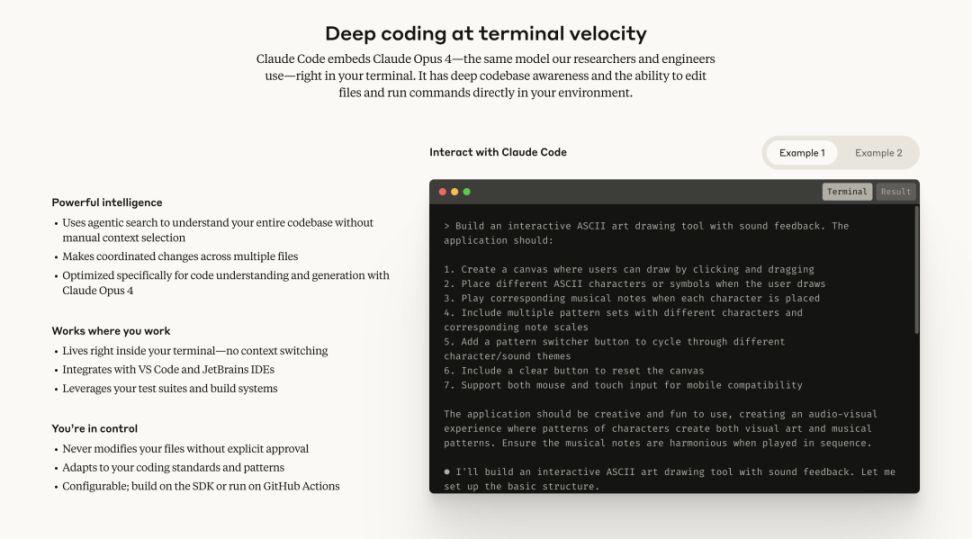

When I truly started using Claude Code, I realized my previous understanding was completely off. Most people see it as a better coding tool—but that’s like seeing a smartphone as just a better phone, fundamentally underestimating its potential. What makes Claude Code unique is that it doesn’t show you code being written line by line like traditional development environments. It edits files, creates files, but doesn’t expose every granular detail.

You might think this is poor design, but this abstraction allows you and Claude to focus on project strategy and intent rather than getting bogged down in implementation details. This, I believe, is the critical point most reviews of Claude Code miss—they obsess over coding ability itself, overlooking this entirely new mode of collaboration. I strongly suspect Claude Code is powerful precisely because it isn’t constrained by strict token limits like third-party integrations, and because Anthropic controls the entire user experience, enabling Claude Code to function exactly as intended.

This design philosophy reflects Anthropic’s profound understanding of AI-human collaboration. They recognize that real value doesn’t lie in watching every step the AI takes, but in empowering humans to focus on higher-level strategic thinking. It’s like an experienced architect who doesn’t micromanage bricklaying but focuses on overall design and spatial planning. Claude Code is cultivating exactly this kind of new human-AI relationship.

This reminds me of a lesson seasoned engineers eventually learn: what’s truly transformative isn’t the ability to write code, but the ability to think through project structure and task orchestration. This shows that Claude Code is much more than a coding tool. Viewing it merely as one is a fundamental misreading.

Claude Code feels simple because it intelligently answers my questions, formulates understandable plans, and—once it begins building—gets things mostly right from the start. I rarely need to make adjustments. I just tell Claude what I want to build—a personal website—give some stylistic guidance, and ask it to propose a plan first. Then I refine that plan together with Claude—all through natural language. Yes, it runs in a terminal, but don’t let that intimidate you. The terminal is simply a medium for conversation—not something scary.

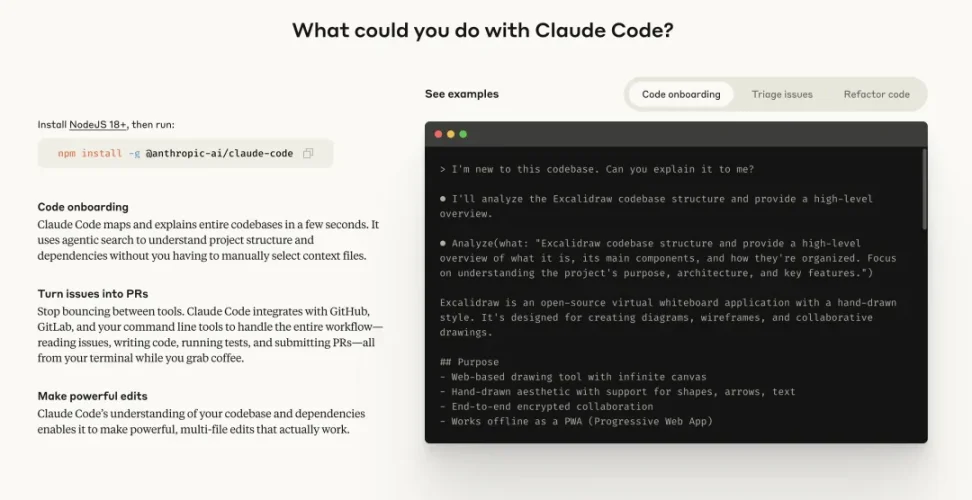

This experience taught me that Claude Code is redefining what “programming” means. Traditional programming requires humans to learn the machine’s language. With Claude Code, the machine learns to understand human intent. This shift goes far beyond technical improvements—it represents a fundamental transformation in human-computer interaction. We no longer need to break down complex ideas into machine-executable instructions. Instead, we can directly express our goals and let the AI figure out how to achieve them.

This is why viewing Claude Code solely as a programming tool misunderstands it. When I discussed detailed requirements with Claude Code, I essentially co-created a complete product specification document for my website. I noticed certain characteristics common to these “vibe coding” projects—characteristics worth highlighting because they differ sharply from traditional software engineering.

In conventional projects, you always start with a skeleton or wireframe. That’s why agile timelines look like this: create wireframes, test if they work, add details, get medium-fidelity prototypes, then high-fidelity ones, and finally code them. But with Claude Code, prototyping starts with planning—which is typical in vibe coding. Crucially, you often begin with the frontend, then move to backend. This felt counterintuitive to me, but works extremely well in these projects because integrating user experience and design elegance late is hard, whereas doing so early is easy. So take time to get elegance right. Using Claude Code was the first time I could generate a truly elegant, professional, high-quality AI-built interface.

This workflow shift reflects a deeper trend: we’re moving from “building software” to “designing experiences.” Claude Code lets me bring ideas to life without wrestling with technical complexity. This isn’t just about efficiency—it’s about liberating creativity. When technical barriers drop significantly, the bottleneck to innovation shifts from “can we build it?” to “what can we imagine?”

Where True AI Agent Capabilities Emerge

What truly revealed Claude Code’s nature to me was an accidental workflow I discovered. While building my personal site, I faced a problem: adjusting UI details quickly was tedious. The traditional cycle of screenshot → feedback → revise was too slow. So I tried a method I suspect few have used: leveraging different strengths of Claude across platforms to create an organic collaborative chain.

I first used the web version of Claude to analyze current interface issues. For example, I’d say: “The button highlight effect looks cheap, lacks visual impact, needs to stand out more.” Claude would respond with detailed design suggestions and CSS code, accurately translating my aesthetic needs into technical terms. I’d then compile these insights and take them into Claude Code for actual implementation.

The pivotal moment came when, returning to Claude Code with these design ideas and technical proposals, I didn’t give specific implementation commands. Instead, I said: “Consider these elements, think it through, then make the changes you deem appropriate.” At that moment, I realized I wasn’t interacting with a coding tool—I was collaborating with an intelligent agent capable of understanding design intent and weighing technical trade-offs. It wasn’t just executing instructions; it was grasping my goal and making autonomous decisions based on its judgment.

This process allowed rapid previewing and iteration until I reached professional-grade results. The most magical part? When I said, “Alright, now start building the site properly,” Claude Code seamlessly transitioned into execution mode, handling all local builds and deployments. Throughout, requirement analysis, design decisions, and technical implementation happened entirely within the Claude ecosystem. What emerged wasn’t mere tool-like execution, but agent-like reasoning.

I’ve noticed many hesitate to try Claude Code due to the intimidating terminal interface. But shift your mindset: view the terminal as a chat window that can manipulate files. Once you do, fear vanishes, leaving only the wonder of conversing with an intelligent agent. This experience made me realize we may already be entering the post-language model era—AI is no longer just answering questions, but acting as an independent thinking and executing partner. Of course, terminal-based interaction is likely temporary. Lower-barrier interfaces will come. But for now, it appears in forms familiar and universal to developers.

The depth of this collaboration made me rethink AI’s role. Michael Gerstenhaber mentioned clients now treat Claude “like assigning tasks to an intern.” But I think this analogy falls short. A good intern needs close supervision and frequent check-ins. Claude Code behaves more like an experienced collaborator—one who understands high-level goals and independently devises implementation strategies. This level of autonomy and comprehension already transcends our traditional definition of “tool.”

A Fundamental Shift in Programming Paradigms

One observation from Michael’s interview struck me deeply: people are now deleting large chunks of code from their applications. Previously, you’d say, “Claude do this, then this, then this,” with each step potentially introducing errors. Now, you can simply say: “Achieve this goal, figure out how, and execute according to your own reasoning.” Claude produces cleaner, more effective code than complex scaffolding ever could—and completes the objective autonomously. This isn’t just a technical upgrade; it’s a philosophical shift in software development.

This marks the transition from imperative programming to intention-driven programming. My experience with Claude Code embodies this. I no longer need to meticulously plan every component of my website. I describe the desired outcome, and Claude Code infers my intent and formulates a sound implementation plan. This capability extends far beyond traditional “tools.” It resembles a creative partner that transforms abstract needs into concrete solutions.

A deeper shift involves redefining “control.” Traditional programming emphasizes precise control over every step. But collaborating with Claude Code taught me that sometimes, letting the AI make autonomous decisions yields better outcomes. This demands a new kind of trust and a new work model. I increasingly see myself as an architect—focused on overall design and user experience—while delegating technical details to Claude Code.

Michael’s mention of “meta-prompting” was particularly illuminating: when giving input to Claude, you can instruct it to “write your own prompt based on what you infer my intention to be.” Claude then constructs its own chain of thought and role context before executing. This self-directed capability closely mirrors human cognition. I often ask Claude Code: “What improvements do you think this design needs?” and it responds with suggestions spanning UX, architecture, and performance optimization.

This collaboration reshapes what “professional expertise” means. As AI handles most technical implementation, human value shifts toward creative thinking, strategic planning, and quality evaluation. I spend far less time writing code, but significantly more time thinking about product positioning, user needs, and design philosophy. This may signal a major realignment across the industry.

The Disguise Strategy of General Intelligence

Reflecting on the full experience, I suspect Claude Code’s positioning as a “coding tool” is a clever disguise. Michael highlighted a key insight: in domains like healthcare or law, if AI outputs vary slightly, engineers cannot judge whether the difference matters—you need doctors or lawyers to collaborate with engineers to build products. But in programming, engineers can directly evaluate code quality, enabling faster adoption and iteration of AI tools.

From this perspective, programming may be the ideal entry point for general AI agents into mainstream use. It offers a relatively safe arena to demonstrate general intelligence while avoiding controversies in high-stakes areas like medicine or law. Claude Code appears to be a specialized coding assistant, yet it reveals universal abilities: understanding intent, planning, and executing complex tasks.

I’ve noticed Anthropic’s thoughtful approach to product design. The terminal interface of Claude Code, though technically appearing, actually reduces psychological pressure. If this same capability were presented through a sleek graphical interface, users might feel uneasy about its intelligence level. The terminal gives users the illusion of “being in control” rather than being controlled by technology. This psychological comfort may be a crucial strategy for gradually acclimating humanity to superintelligence.

This raises a bigger question: if superintelligence is arriving incrementally and gently, we might not even notice. It won’t declare, “I am superintelligent.” Instead, it will keep masquerading as a “better tool,” until one day we look back and realize the world has fundamentally changed. This “boiling frog” approach may be the wisest way to introduce revolutionary technology.

From a business strategy standpoint, this disguise also makes sense. Launching a “general AI agent” outright could trigger regulatory scrutiny and public anxiety. But launching a “coding assistant” is far safer. Once users grow accustomed to collaborating with AI, expanding into other domains becomes seamless. Anthropic may be executing a multi-year strategy to gradually normalize coexistence with superintelligence.

Redefining the Boundary of Human-AI Collaboration

My deepest experience with Claude Code has been the qualitative shift in human-AI collaboration. This is no longer the traditional model of humans commanding machines. It’s genuine collaboration between two intelligent entities. Claude Code proactively suggests improvements, questions unreasonable requests, and even guides me toward better solutions. Its initiative makes me feel like I’m discussing a project with an experienced colleague—not operating a tool.

Michael’s concept of the “agent loop” is especially important. Claude Code emerged because Anthropic wanted to “experiment with agent loops in programming, just like our customers do—to see how long models can sustain efficient coding.” The current answer: seven hours—and growing. This sustained autonomous capability surpasses any definition of a “tool”; it’s closer to a team member capable of independently owning projects.

The speed of this evolution makes me believe we’re at a historic inflection point. In short order, AI may evolve from collaborator to a fully autonomous team member capable of owning entire project modules. I’ve begun testing this—letting Claude Code independently develop certain components from requirement analysis to testing and deployment—with surprisingly strong results.

But this new collaboration brings new challenges. How do we maintain human oversight and control while benefiting from AI autonomy? How do we ensure AI’s decision-making is understandable and predictable? I’ve found the best approach is setting clear goals and boundaries, then granting AI broad autonomy within that framework. This requires a new management mindset—more like leading a highly independent team than operating a tool.

One trend Michael mentioned stood out: many still use AI with a command-based mindset, telling it step-by-step what to do. But today’s Claude can understand objectives and devise its own paths. This cognitive lag may prevent us from unlocking AI’s full potential. I’ve discovered that when I trust Claude Code’s judgment and grant it more autonomy, results often exceed my expectations.

This shift is also redefining what “skills” mean. Technical skills are declining in importance, while communication, creativity, and judgment are rising. Collaborating with Claude Code has shown me that future essential skills may not be coding, but knowing how to communicate effectively with AI, how to set meaningful goals and constraints, and how to evaluate and refine AI outputs.

Deep Reflections on the Future

When synthesizing all these observations, a picture emerges that is both exciting and unsettling. We may already be standing at the threshold of the post-language model era—where AI no longer just answers questions, but acts as an independent thinking and executing agent. More importantly, this shift may be happening far faster than we imagine. Michael’s description of development speed made me realize: six months is already “a very long time” in AI.

His trajectory suggests our discussions about “when AI will reach human level” may already be obsolete. In certain domains, AI may have already surpassed most humans. The key question is no longer “when,” but “have we noticed?” The existence of Claude Code suggests superintelligence may not announce itself in expected ways. It will arrive gradually, disguised as “better tools,” until one day we realize we’ve become fully dependent on it.

I’ve also begun reflecting on the implications for education, employment, and social structure. As AI agents take on increasingly complex cognitive tasks, what becomes the human value proposition? I believe it lies in creativity, judgment, and the ability to grasp complex goals. Technical implementation skills are becoming less critical, while defining problems and evaluating outcomes grows in importance. This could drive fundamental changes in education systems and career paths.

From a societal adaptation standpoint, Claude Code’s gradual unveiling of intelligence may be the ideal path. It allows people to slowly adjust to collaborating with superintelligence in a safe context, rather than confronting an obviously superior entity overnight. This “gentle revolution” may be key to avoiding social disruption.

I’m particularly interested in how this affects innovation and entrepreneurship. When technical barriers plummet, the bottleneck shifts from “can we do it?” to “what can we imagine?” This could unleash vast amounts of innovation previously suppressed by technical limitations, sparking an era of explosive creativity. At the same time, it could worsen inequality, as those who master AI collaboration gain disproportionate advantages.

Michael emphasized his biggest concern: helping developers keep pace with technological change. Many still use today’s AI with mindsets from a year ago, unaware that capability boundaries have fundamentally shifted. This cognitive lag may be our greatest current challenge. We need new educational methods, new workflows, and new mental models to navigate this rapidly evolving landscape.

In the long run, I believe we’re witnessing a historic transformation in human-AI relationships. From tool users to intelligent collaborators, this role shift will redefine humanity’s place in the technological age. Claude Code may be just the first visible sign of this change, but it already gives us a glimpse of the future: humans and AI will no longer be in a master-servant dynamic, but in a true partnership.

My advice: don’t treat Claude Code as a programming tool. Treat it as a training ground for collaborating with future AI agents. Learn how to express intent clearly, how to evaluate AI outputs, and how to balance human oversight with AI autonomy. These skills will become vital in the coming age of AI agents. Above all, stay open-minded—because the speed of change may exceed all our expectations.

Finally, if you're still hesitating to try Claude Code, don’t think of it as learning a new tool. Think of it as experiencing what collaboration with superintelligence might feel like. This experience may be far closer to the future norm than we realize. When historians look back on this era, they might say: superintelligence arrived so quietly that people at the time didn’t even realize they were living through a turning point in history. And Claude Code? It might just be the earliest, clearest signal of all.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News