"Wealthy yet naive": Singapore, a hunting ground for scammers

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

"Wealthy yet naive": Singapore, a hunting ground for scammers

Singapore, this "wealth haven," is becoming a "hunting ground" in the eyes of scammers.

Singapore, this "wealth haven," is becoming a "hunting ground" in the eyes of scammers.

As the number of family offices surges and high-net-worth individuals flood in, sophisticated scams are quietly emerging in Singapore: from fraudsters posing as investment advisors infiltrating the core of family wealth, to orchestrating virtual asset schemes and impersonating bank staff for cross-border fraud.

Criminals target regulatory loopholes and blind spots of trust, setting traps layer by layer, leaving some wealthy individuals and ordinary citizens deeply ensnared and suffering massive financial losses. On the surface, Singapore appears to have robust rule of law and mature systems, yet it now faces a dual challenge concerning wealth security and regulatory upgrades.

"Six out of ten people have encountered scams"

In late 2024, Lee, a sales professional, suddenly received a message on WhatsApp from a foreign number offering her an online side job. Considering her job mundane, Lee readily agreed.

Soon after, another man contacted her, claiming to be a married Malaysian living in Singapore with a child. Although she suspected it might be a scam, she decided to play along. "I just wanted to scare the scammers. I thought I could outsmart them."

For months, the man sent her encouraging and cheerful messages daily. Gradually, Lee began seeing him as a real friend. "He would ask every day, 'Sister, how are you? Want to try this online job?' Over time, I convinced myself it was just a part-time gig that could earn me extra money."

The job allegedly required her to deposit collateral in cryptocurrency and complete surveys linked to about 30 brands, after which she could withdraw both the deposit and commission. Initially, Lee’s deposited funds quickly generated returns far exceeding her principal, prompting her to increase her investments. It wasn’t until she had deposited over $11,000 that the cryptocurrency platform suspended transfers and warned her via email that she might have been defrauded.

Yet Lee still trusted the man—until the platform demanded a $120,000 investment, which she couldn't afford. That's when she finally realized the truth. By then, she had already transferred $78,000, only to be told she couldn’t withdraw any funds until the task was completed.

Devastated, Lee pleaded for the return of her hard-earned money but was refused and instead advised to borrow from banks or licensed lenders.

Lee isn’t alone. Several others lost $167,000 simply by clicking on fraudulent ads on Facebook or Instagram.

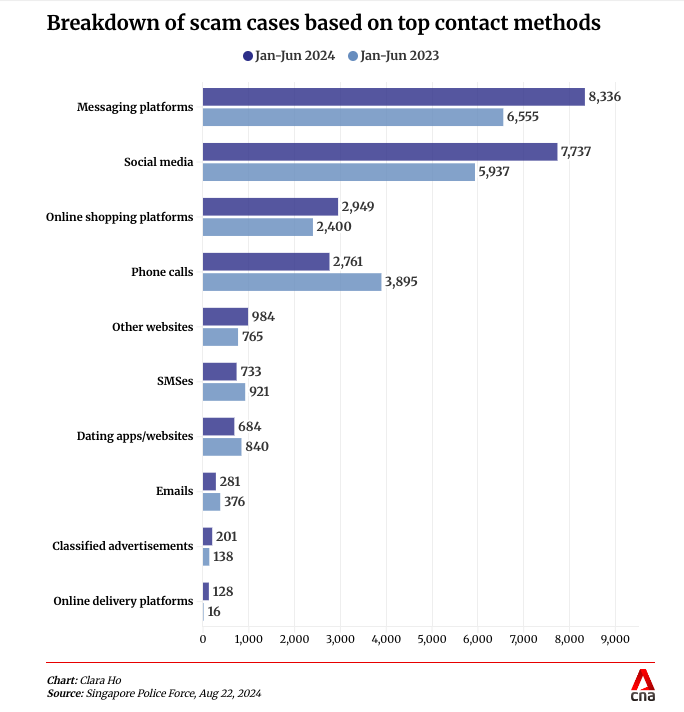

Data shows that in Singapore, six out of every ten people have experienced scams. The government reports nearly half of these scam cases originate from Meta platforms—Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram.

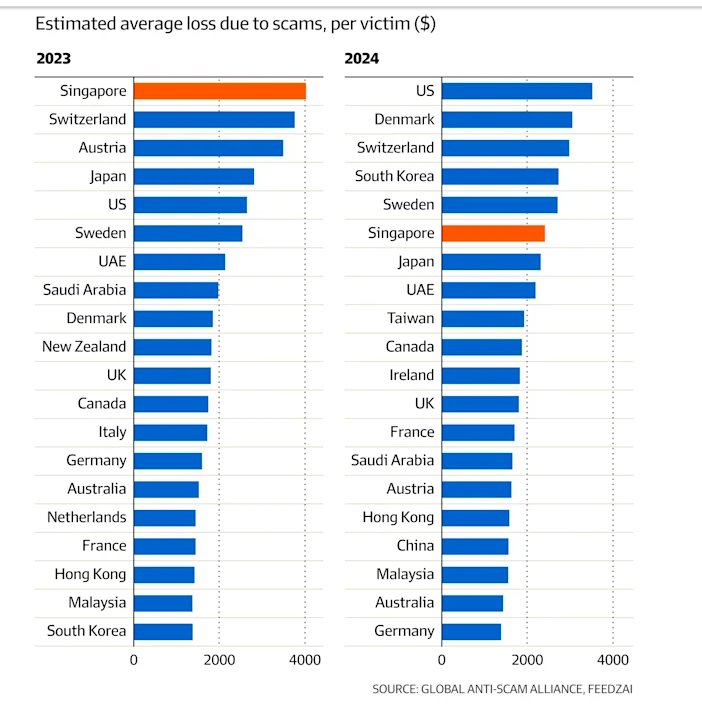

Historically and currently, Singaporeans rank among the world's most heavily targeted populations for scams. In 2023, the average loss per person in Singapore reached $4,031—the highest national average globally.

Since 2019, both the number of scam cases and total losses in Singapore have hit record highs annually. In 2024, there were 51,501 reported scam cases involving over $1.1 billion—the first time annual scam losses surpassed the $1 billion mark. Police recovered only about $182 million, while more than two-thirds of victims did not report the crimes.

In 2025 alone, between January and April, over 13,000 scam cases were reported in Singapore, with victims losing more than $313.7 million.

"Wealthy yet naive"

Even the "wealthy" are not immune to scams.

Mike (a pseudonym), a Singaporean actor, always reminded himself to stay vigilant against scams, especially online ones. But when he met a young Filipino woman named Debra on a dating site, he couldn’t resist engaging with her.

Over several months, Debra convinced Mike to invest nearly S$40,000 ($30,000) in cryptocurrency into an e-commerce venture. When he discovered his investment had yielded nothing, Mike requested a video call—only to find the person on screen bore little resemblance to the photos in her profile.

Mike is not the only affluent individual who has fallen victim.

Since 2017, a criminal group invited Chinese entrepreneurs to Singapore to sign contracts, charging them "management fees" or "administrative fees." They leased office spaces in locations like Marina Bay Financial Centre to create a legitimate appearance, supported by fake contracts mimicking high-end operations. At least 10 business owners were defrauded, totaling over S$2.5 million.

In March 2025, during a cross-border operation, a finance director in Singapore was tricked into transferring approximately S$499,000 after being contacted via Deepfake technology simulating a video and phone call from his multinational company's CEO. Fortunately, through international cooperation, police successfully recovered the funds.

In early 2025, a Singapore-based financial advisor was scammed out of S$1.2 million by imposters posing as agents from the Anti-Scam Centre, who falsely claimed he was involved in money laundering and needed to cooperate with an investigation.

In March 2025, Singapore’s High Court ordered private trustees handling the bankruptcy estate of Ng Yu Zhi, a suspect in a major fraud case, to accept a US$12 million claim from creditors—an amount previously rejected. Ng Yu Zhi had operated a series of Envy-branded companies running a fictitious nickel trading scheme, raising around S$1.5 billion since 2017.

The scheme promised quarterly returns of 15%, using forged transaction records and histories. Early investors receiving payouts helped lure in more victims. The case involves nearly 300 (high-net-worth) victims and S$1.5 billion in total funds, remains under trial, and is considered the “largest metal fraud in Singapore’s history.”

In March 2025, a Chinese billionaire sued four former employees, accusing them of siphoning funds from his Singapore-based family offices, Panda Enterprise and LFI, through fraudulent transactions and false claims over many years. This incident highlights vulnerabilities within certain family office structures.

The billionaire, Zhong Renhai, who controls Panda Enterprise and LFI, alleged that the four ex-employees abused his trust over years, transferring S$74 million (approximately RMB 400 million) into their own accounts or misappropriating his funds without authorization.

Indeed, these "wealthy individuals" often prove easier targets. As one asset recovery insider put it: "They are wealthy yet naive."

Even Temasek got scammed

In 2025, Senior Minister of State Liu Yanling and Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund Temasek issued public warnings about an investment scam involving a manipulated photo of Liu, a fake app, and a WeChat group—all promoting Chinese financial products.

In the altered image, Liu appeared at a ceremony where two fictional organizations—a Chinese Chamber of Commerce and an asset management firm called Taibai—signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU).

On May 12, Temasek clarified that although Tai Bai Investments is one of its wholly owned subsidiaries, it has no connection to the Tai Bai app or WeChat chat groups. Liu Yanling stated on her Facebook post the same day that the original photo was taken at the Singapore-China Economic Partnership Conference on February 1, 2024, and included comparisons of the authentic and doctored images.

Tai Bai Investments and Temasek confirmed they do not sell or market investment products in China, nor have they authorized any third party to do so. Reports indicate multiple individuals have already lost substantial sums through the Tai Bai Wealth Management app.

Beyond this, Temasek previously suffered losses investing in two fraudulent firms—FTX and eFishery—and decided to cut its investments in early-stage companies by 88% over three years.

As one of FTX’s largest investors, Temasek joined SoftBank, BlackRock, and other institutional investors—including Sequoia Capital—as victims of what became the biggest cryptocurrency scam in history.

This investment accounted for about 0.1% of Temasek’s portfolio in FY2023, resulting in millions in losses—an outcome described as “embarrassing.”

According to its financial report ending March 31, 2023, Temasek recorded a net loss of $7.3 billion for FY2023. After writing off the FTX investment, some Singapore lawmakers questioned the organization’s due diligence processes.

Although Temasek said it conducted “extensive due diligence” on FTX from February to October 2021—lasting about eight months—it acknowledged: “It is clear from this investment that our trust in Sam Bankman-Fried’s behavior, judgment, and leadership stemmed from our interactions with him and views expressed in discussions with others—but in hindsight, that trust appears misplaced.”

The impact of this failed investment went beyond finances. Then-Finance Minister Lawrence Wong (now Prime Minister) publicly stated the investment damaged Temasek’s reputation. Subsequently, Temasek implemented pay cuts for its investment team and senior management.

Even more shocking was Temasek’s failed investment in Indonesian agritech startup eFishery. The company, which developed automated feeding systems for fish and shrimp farming, was exposed for allegedly falsifying sales and profit data. Media reports in April revealed that one of eFishery’s founders admitted to fabricating figures in the company’s financial statements.

Portrait of the "Hunters"

In Singapore, scams are diverse and complex, including phishing, investment frauds, impersonation scams, e-commerce fraud, job scams, romance scams, application fraud, credit card fraud, email scams, online dating fraud, identity theft, malware, sextortion, loan scams, and more.

Scam cases are “as numerous as stars,” with the Singapore Police Force (SPF) website publishing new scam alerts and case details almost daily.

For example, according to an SPF announcement on June 11, 2025, multiple victims reported falling prey to Government Official Impersonation Scams (GOIS), where fraudsters posed as staff from the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS). Victims’ funds were transferred to credit cards and used for unauthorized transactions, amounting to over $262,000 in losses.

Overall, scammers in Singapore continuously upgrade their tactics—from traditional telecom fraud to “bespoke” financial deceptions, from impersonating bank personnel to posing as seasoned fund managers or even government officials. They increasingly exploit Singapore’s own strengths as tools in their deceptive narratives.

First, impersonating professional advisors. Scammers often pose as representatives from law firms, family office consultants, audit experts, or even MAS officers. They forge documents, email domains, logos, and scripts to make victims believe they are communicating with legitimate institutions.

Second, packaging a “compliant identity.” Fraud rings leverage Singapore’s global credibility by forging local company registration details, presenting fake bank partnership proofs, and leasing prestigious office spaces such as those in Marina Bay Financial Centre to enhance the “authenticity” of their scams.

Third, building a trust loop. These scammers don’t rush to strike. Instead, they maintain long-term contact with targets, gradually establishing a seemingly solid chain of trust. By attending the same social circles, charity events, or business forums, they position themselves as “insiders,” strengthening relationships ahead of the final “harvest.”

Fourth, leveraging new technological tools. AI-generated videos, voice cloning, and ChatGPT-written investment reports have become precision weapons enabling them to deceive even seasoned investors.

Worse still, some financial institutions have unintentionally—or even knowingly—become enablers. In 2020, a Singapore trust company was fined USD 793,000 (SGD 1.1 million) for serious breaches of MAS anti-money laundering/countering the financing of terrorism regulations across multiple accounts. According to MAS, the violations occurred over more than a decade, from 2007 to 2018.

Additionally, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) revealed that the trust firm recruited clients in the U.S. for Cook Islands trusts—a type of wealth and asset management vehicle known for being highly secure and difficult to penetrate.

The dark currents beneath family office boom

Singapore, a globally renowned wealth management hub, attracts vast international capital thanks to its strict legal system, low tax environment, highly transparent financial framework, and immigration policies favorable to high-net-worth individuals. In recent years, increasing numbers of family offices have established themselves in Singapore, managing private wealth from around the world.

Data indicates that by the end of 2024, over 2,000 family offices had set up operations in Singapore.

Yet, as the saying goes, “Where there is wealth, there is risk.” Behind this façade of safety and prosperity, a silent hunting operation unfolds in parallel. Targeting family offices and high-net-worth individual investors, scammers meticulously design schemes, master the art of disguise, and quietly infiltrate, seeking to extract massive illegal gains from this gilded land.

While enjoying the fruits of wealth, high-net-worth individuals are increasingly becoming prime targets in carefully orchestrated “hunts.” So why do these individuals—who intuitively should possess strong risk awareness and investment judgment—so frequently fall victim? Underlying this trend are psychological traits and structural vulnerabilities unique to the wealthy class.

First, information silos and relationship-driven decision-making. Many family offices operate based on networks of personal connections, relying on referrals from “trusted circles.” Risk assessments are often replaced by trust rather than rigorous due diligence. Scammers precisely exploit this weakness, breaking defenses through “internal recommendations.”

Second, excessive trust in the “Singapore label.” Phrases like “this is a Singapore-registered company” or “this project is registered with MAS” often serve as immunity passes. High-net-worth individuals place immense faith in local regulation, overlooking whether the entity behind the name operates legitimately.

Third, pursuit of “high confidentiality + high returns.” Some seek secretive asset allocations with high yields while evading overseas oversight. These very desires become the perfect “talking points” scammers love to exploit.

Fourth, the misconception of “delegating to children.” Many wealthy individuals entrust financial matters to younger generations or assistants, reducing direct involvement and lowering vigilance—creating openings for scammers.

Why do scammers favor Singapore?

The reasons why scammers are drawn to Singapore are no accident—they stem directly from the city-state’s unique economic structure, societal trust environment, and global reputation.

First, a financial hub with seamless capital flows. As one of the world’s most important financial centers, Singapore offers highly free capital movement, open foreign exchange policies, and a flexible banking system, making cross-border financial operations extremely convenient. For scammers, this creates an ideal environment for “money laundering.”

Second, favorable tax regime and strong privacy protections. With low tax rates and robust financial privacy—especially well-developed trust and family office frameworks—many wealthy individuals, including those with questionable sources of funds, can establish shell companies or family offices under a “legal facade” for asset allocation and fund transfers.

Third, ease of obtaining “legitimate status.” Singapore’s investment immigration program was once relatively lenient, allowing fraudsters or money launderers to gain long-term residency or citizenship through investment, thereby legitimizing their presence. This makes Singapore attractive as a “stepping stone” or “safe house” for criminals.

Fourth, social stability and trusted legal system. Compared to traditional tax havens like Caribbean island nations, Singapore enjoys higher legal integrity and financial credibility. Criminals can more easily “hide in plain sight” here, maintaining a long-term image of a legitimate high-net-worth individual.

Fifth, massive inflows of international capital create screening pressure. As a key destination for global asset allocation, Singapore absorbs vast amounts of international funds. Financial institutions face enormous anti-money laundering compliance burdens, making it difficult to scrutinize every transaction—creating exploitable gaps.

Sixth, high tolerance for “surface-level compliance.” Some banks, trusts, and family office service providers accept clients based solely on formal compliance—such as providing ID and proof of income—without probing deeper substantive issues. This allows “pseudo-high-net-worth” individuals or “fake family offices” to slip through the cracks.

Moreover, cross-border law enforcement collaboration remains challenging. Many scammers don’t commit fraud in Singapore itself but route illicit funds into the country. Since criminal acts occur elsewhere while funds reside in Singapore, local authorities often require cooperation from other jurisdictions—leading to inconsistent efficiency and enabling some criminals to evade justice.

With Singapore embracing digital transactions and cashless payments, scammers are adapting their strategies to target digital wallets and online platforms, leading to increased phishing and malware-related fraud.

A "haven"—and a battlefield

Over the past five decades, Singapore has thrived through its global and regional hub strategy. However, as Southeast Asia grapples with rising transnational crime, challenges from illicit financial flows are growing ever more severe.

Scammers flocking to Singapore is not because the country “tolerates” crime, but because its highly developed, free, and mature financial system inherently offers opportunities for bad actors to skirt the rules. Policies under intense scrutiny include the family office program and a lesser-known loophole that enables criminal activity.

For many criminals and corrupt figures across the region, Singapore is the perfect “escape destination”: a major financial center through which illicit actors can access the global financial system, move dirty money worldwide—or hide it locally through suspicious real estate deals right under the noses of Singaporean authorities.

Beyond its prestige, Singapore’s booming banking sector not only drives employment, supports the local economy, and boosts property values—but also presents persistent compliance challenges.

Following major money laundering scandals in 2022–2023, Singapore strengthened its anti-money laundering regulations. Yet striking a balance between regulation and operational freedom for financial firms remains difficult—a delicate act for a trade city with global and regional influence.

(TechFlow提醒: Content and viewpoints are for reference only and do not constitute any investment advice.)

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News