Why Gamblers Ultimately Lose Everything: Survival Rules in Non-Ergodic Systems

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Why Gamblers Ultimately Lose Everything: Survival Rules in Non-Ergodic Systems

We always feel that one more round will turn things around, precisely because we mistakenly treat the group average as individual destiny.

Author: Xue'e, DataCafe

Imagine you start a coin-flipping game with 1,000 yuan and can choose to keep playing indefinitely:

In each round, you flip a coin once.

If it lands heads, your wealth increases by 80%.

If it lands tails, your wealth decreases by 50%.

This sounds like a sure-win game!

But in reality…

If 100,000 players participate and each plays 100 rounds, you’ll find that while their average wealth is indeed growing exponentially, the vast majority end up with less than 72 yuan—or even go bankrupt!

Why does average wealth grow while most individuals get poorer over time?

This is a classic example of the non-ergodicity trap. The illusion that “just one more round” will turn things around stems precisely from our mistaken belief that group averages reflect individual destinies.

The Trap of Non-Ergodicity: Long-Term Average ≠ Your Actual Fate

What is ergodicity?

The concept of ergodicity originated in statistical physics and has since had profound implications in probability theory, finance, behavioral science, and machine learning. At its core, it asks: Does the long-term average apply to the individual? When making decisions, should we trust the "long-term average," or our own repeated real-life experiences?

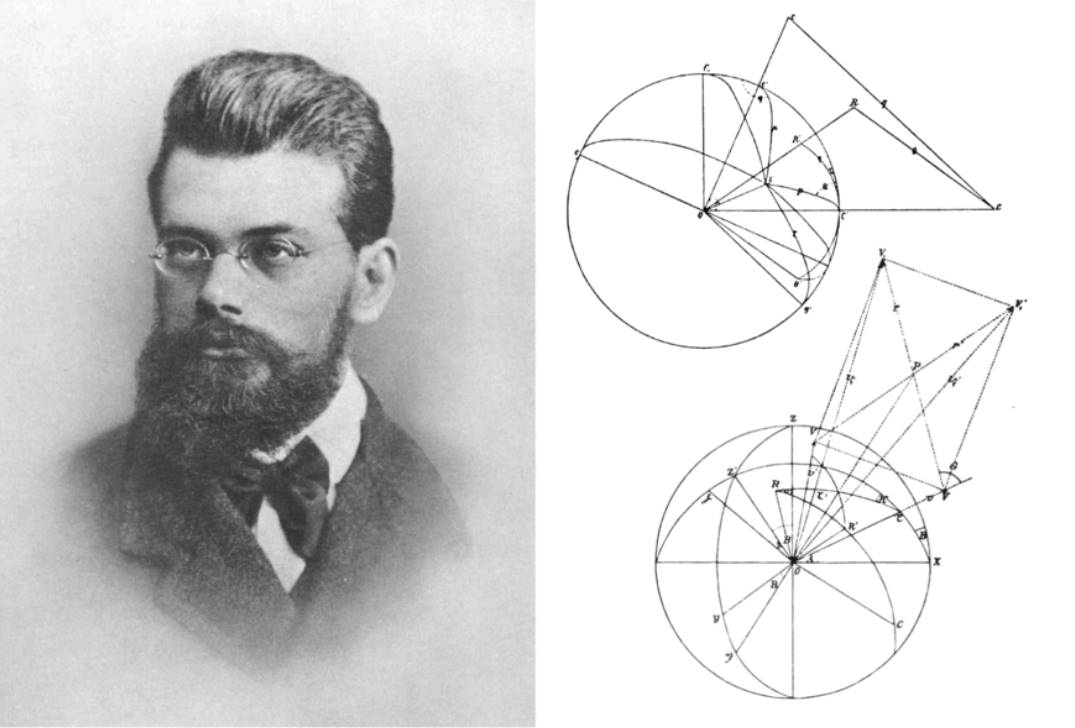

In the 19th century, physicist Ludwig Boltzmann proposed the ergodic hypothesis while studying gas molecule motion: if you observe a single gas molecule for long enough, it will eventually pass through all possible states.

Picture a sealed container filled with countless gas molecules, each undergoing different velocity trajectories as they collide. The long-term trajectory of a single molecule matches the statistical distribution of the entire gas—meaning we can use the state of all molecules at a single moment to infer the long-term behavior of any individual molecule.

This is the famous Boltzmann ergodic hypothesis.

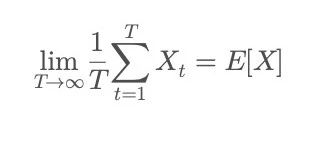

Mathematically, ergodicity means:

The left side represents the time average—the average outcome for an individual experiencing the same process repeatedly over a sufficiently long period;

The right side represents the ensemble average—the expected value derived from observing many individuals at a single point in time. In other words, when a system is ergodic, an individual's performance eventually converges to the group’s “long-term average.”

If the world were ergodic, everyone's wealth would eventually approach the societal average. In such a world, everyone would experience all possible economic states (rich, poor, success, failure), and individual fates would converge to the group’s long-term average.

But real life is often non-ergodic: individuals have limited resources and frequently exit the game entirely before experiencing all possible paths due to a single failure.

We often hear seemingly persuasive statements like:

"The average annual income in this industry exceeds one million."

"Someone achieved financial freedom by age 30 after just two years of entrepreneurship."

"This index fund offers high long-term annualized returns—if you just keep investing, you'll get rich."

…

These plausible statistics appear to reveal a certain truth—that action alone ensures the long-term average applies to you. But these cases represent path-dependent, non-replicable, non-ergodic processes. Imitators cannot replicate the same historical context, network connections, lucky breaks, or even know how many unseen failures exist behind the scenes.

Data shows you the group’s long-term average, but reality is full of short-term “cliff-like collapses.”

This is the most insidious trap of non-ergodicity—big data averages ≠ individual reality.

A single collapse may be irreparable for an individual; one failure could knock you out permanently, preventing any return to the “average state.” Each of us lives only one life path—we can't rely on the casino-style law of large numbers where probabilities even out across many gamblers.

Why Do Most Individuals End Up Worse Than the “Average”?

In non-ergodic systems, individual long-term outcomes are typically worse than the group average. This isn’t random—it’s a systemic structural feature. The appealing average is often inflated by rare outliers: entrepreneurial successes, investment windfalls, rags-to-riches stories—while the silent majority of failures never make it into the statistics.

Real-world systems are mostly multiplicative and exhibit path dependence—such as compound interest in investing, health deterioration, or reputational damage. These systems share a key trait: upside is limited, downside is unbounded.

One bankruptcy can ruin a lifetime;

One wrong decision can alter destiny forever;

One betrayal can destroy trust completely;

Yet gains in wealth, performance, or advantage are always finite.

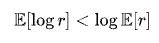

This is why mathematically, the long-term growth rate in multiplicative processes does not equal the “arithmetic average return,” but instead closely follows:

In contrast, the group average typically uses arithmetic mean:

And because the logarithmic function is strictly concave, Jensen’s inequality implies:

Therefore, the long-term growth rate (i.e., geometric mean) in multiplicative systems is always less than the arithmetic mean. The greater the volatility, the wider this gap. The arithmetic mean tells you 'what happens if you’re lucky forever,' while the geometric mean reveals 'how much remains after weathering real-world storms.'

This means individual long-term outcomes consistently fall far below the “group average return”—not due to bad luck, but structural necessity.

How to Make Optimal Decisions? Kelly’s Golden Rule

So in life decisions, what can we do to avoid eventual ruin in long-term games? How can we survive without going bankrupt while achieving sustainable compounding?

The answer: Never go all-in. Learn to bet using the Kelly Criterion!

The Kelly Criterion is an optimal betting strategy for repeated games, designed to maximize long-term growth while avoiding short-term ruin. It was first introduced in 1956 by John L. Kelly Jr. at Bell Labs, originally to solve the problem of “how to allocate signal power in noisy communication channels” to maximize information transmission efficiency.

Soon after, the theory crossed boundaries.

Mathematician and investing genius Edward Thorp realized the Kelly formula could optimize wealth growth paths. He brought it into casinos, systematically beating blackjack dealers in his book *Beat the Dealer*, then took it to Wall Street, continuing to “harvest” profits in *Beat the Market*.

The criterion is essentially equivalent to maximizing expected logarithmic utility, thus balancing growth and risk dynamically. It helps you find the optimal balance between “staying alive” and “earning enough.”

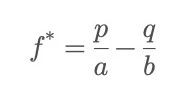

Kelly Formula:

Where p is the probability of winning, q = 1−p is the probability of losing; b is the net odds received on the bet (gain per unit wagered, excluding principal), and a is the fraction lost upon loss (usually 1, if the entire bet amount is lost).

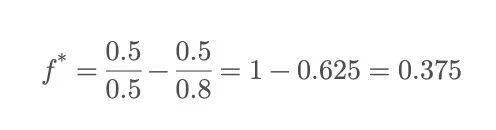

Returning to the coin-flip game introduced earlier, suppose you can choose to bet a fixed fraction of your bankroll repeatedly—but what fraction is optimal?

In other words, the Kelly formula recommends betting 37.5% of your current capital each time. Betting too much—even with an edge—can lead to ruin from a few consecutive losses; betting too little misses out on potential growth.

The significance of the Kelly formula lies in: finding the sweet spot where you grow the most while still surviving.

One caveat: the Kelly formula is highly sensitive to win rates and payout odds, which are often uncertain or changing in reality. Thus, many prudent practitioners use half the Kelly recommendation (“half-Kelly strategy”) to achieve smoother equity curves.

Simulation: 100,000 Coin Flips—How Many Players “Survive”?

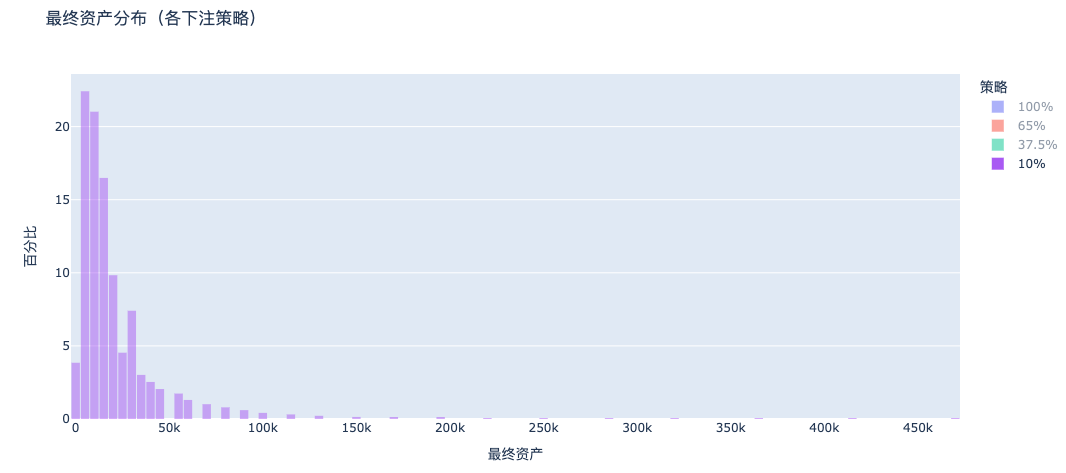

To better understand how different betting strategies affect individual fates, I simulated 100,000 players participating in the initial coin-flip game over 200 rounds, each playing independently.

The rules remain: starting capital of 1,000 yuan, +80% on heads, −50% on tails. Players choose fixed betting fractions: e.g., 100%, 65%, 37.5%, etc.

The result… nearly all players who bet 100% go bust!

Final wealth follows a “power-law distribution”: a tiny number become extremely wealthy, while the vast majority go bankrupt.

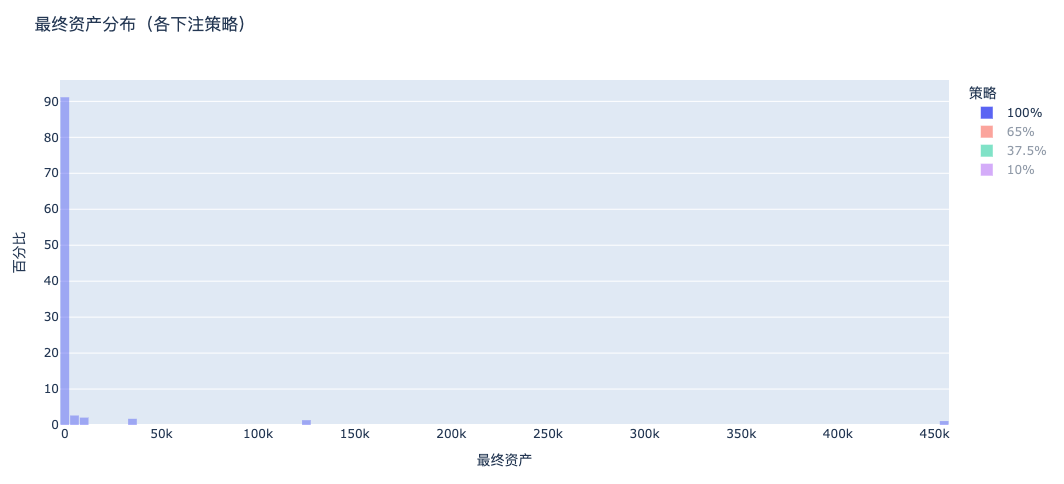

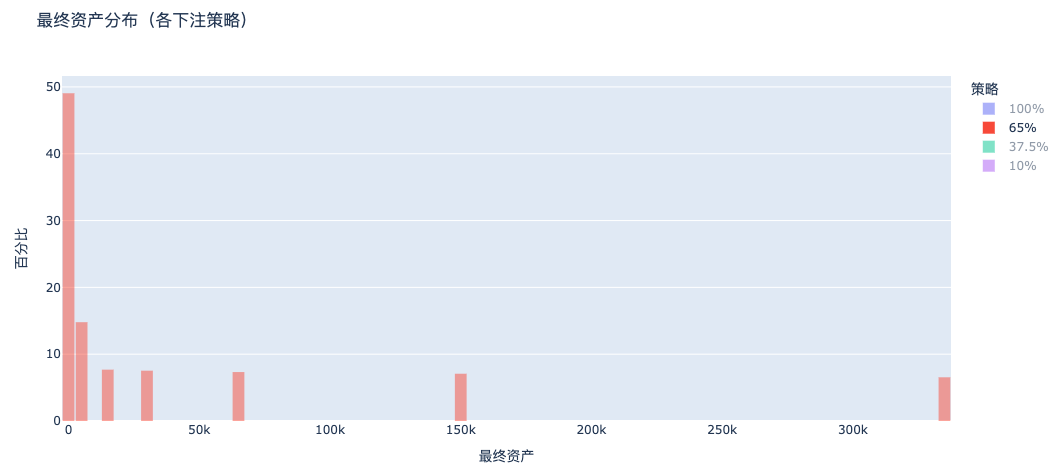

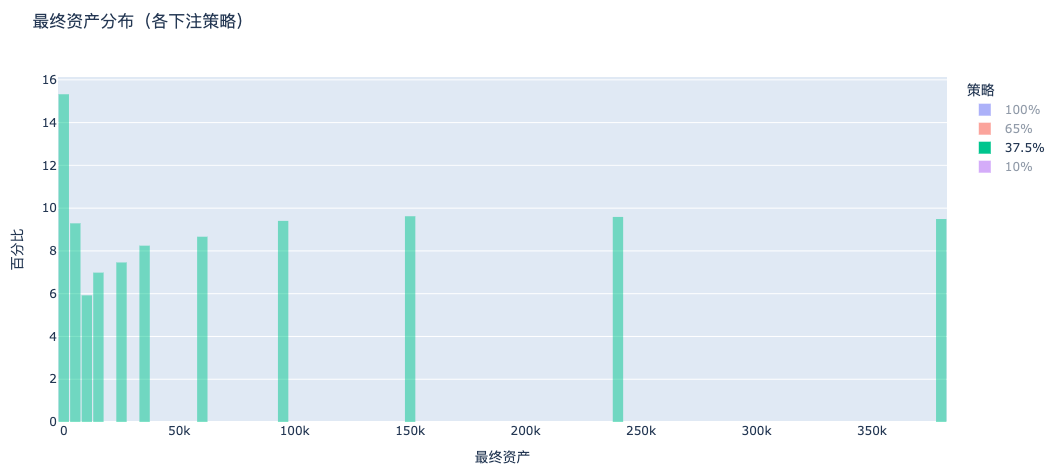

We compare four different betting strategies, with distributions skewed right indicating higher player assets.

a. Betting 100%: Almost everyone goes bankrupt

The final asset distribution under full-bet strategy shows a massive left-side poverty peak and an extremely thin right tail: most people go broke, a few take all—the true picture of asymmetric payoff + survivorship bias.

b. Betting 65%: Still highly polarized, many still go bankrupt

c. Betting 37.5% (Kelly Criterion): Steady wealth growth

Under the Kelly strategy, the asset distribution clearly shifts right—most players grow wealth with concentrated results—making it the optimal wealth accumulation model.

d. Betting 10%: Almost no one goes bankrupt, but returns are too low

Gone is the sharp left peak of ruin seen in all-in betting, but overall wealth clusters in the low-asset zone. In contrast, the 37.5% strategy produces a clear long right tail, enabling substantial asset multiplication.

Kelly betting is the only strategy that balances “surviving in most cases” and “achieving meaningful growth”—mathematically optimal for long-term survival. This is the essence of the Kelly formula: It doesn’t maximize your winnings—it ensures you stay in the game long enough to benefit from them.

Life Philosophy in the Kelly Formula

The Kelly formula teaches us that the secret to long-term success lies in managing your “bet size.” Life isn’t about who lands the biggest single hit—it’s about who keeps playing.

In careers: it’s neither quitting impulsively nor staying stuck in comfort zones, but continuously building skills, being open to change, and preserving options;

In investing: it’s not betting everything on a big score, but managing position sizes based on odds and keeping chips in play;

In relationships: it’s not placing all emotional value on one person, but giving love while maintaining self-worth;

In personal growth and discipline: it’s not relying on bursts of motivation, but steadily optimizing life structures through compounding habits.

Life is a long game. Your goal isn’t to win once—but to ensure you never get eliminated. As long as you stay in the game, good things will eventually happen.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News