Vitalik's new article: A brief discussion on the mathematical principles of reasonably categorizing L2 stages

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik's new article: A brief discussion on the mathematical principles of reasonably categorizing L2 stages

Combining human governance with mechanisms makes the second phase of L2 more antifragile.

Author: Vitalik Buterin

Translation: Wenser, Odaily Planet Daily

Editor's note: The discussion around the three stages of Ethereum rollup security has long been a focal point within the Ethereum ecosystem community. This is not only crucial for the operational stability of the Ethereum mainnet and L2 networks but also closely tied to the real development status of L2 networks. Recently, Ethereum community member Daniel Wang proposed on X a naming label #BattleTested for L2 networks at Stage 2, suggesting that only L2 networks whose code and configuration have been live on the Ethereum mainnet for over six months, consistently maintaining a total value locked (TVL) exceeding $100 million—with at least $50 million in ETH and major stablecoins—should earn this designation. This status would be dynamically evaluated to prevent the emergence of "ghost chains" on-chain. Subsequently, Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin provided a detailed explanation and shared his views on the matter, which are translated below by Odaily Planet Daily.

The Three Stages of L2 Networks: From 0 to 1 to 2, Security Determined by Governance Share

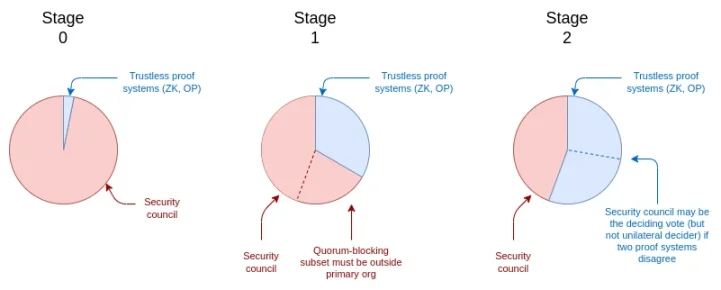

The three stages of Ethereum rollup security can be determined by when the security council can override trustless (i.e., purely cryptographic or game-theoretic) components:

-

Stage 0: The security council holds full control. There may be an operational proof system (Optimism or ZK mode), but the security council can overturn it via a simple majority vote. Thus, the proof system is merely "advisory."

-

Stage 1: The security council requires 75% approval (at least 6 out of 8 members) to override the system. A quorum-blocking subset (e.g., ≥3 members) must exist outside the primary organization. Therefore, taking control of the proof system is relatively difficult, though not impossible.

-

Stage 2: The security council can act only in cases of provable errors. For example, a provable error could occur if two redundant proof systems (e.g., OP and ZK) contradict each other. In such cases, the council can only choose one of the submitted answers—it cannot arbitrarily respond to any mechanism.

We can represent the "voting share" held by the security council across these stages with the following chart:

Governance voting structure across the three stages

An important question is: what are the optimal timings for an L2 network to transition from Stage 0 to Stage 1, and then from Stage 1 to Stage 2?

The only valid reason not to immediately enter Stage 2 is a lack of complete trust in the proof system—a understandable concern: the system consists of a large amount of code, and if there are bugs, attackers might steal all user assets. The more confidence you have in the proof system (or conversely, the less confidence you have in the security council), the more you would want to push the entire network ecosystem toward the next stage.

In fact, we can use a simplified mathematical model to quantify this. First, let's list the assumptions:

-

Each member of the security council has a 10% chance of "individual failure";

-

We treat liveness failures (refusing to sign contracts or key unavailability) and safety failures (signing incorrect data or compromised keys) as equally likely. In practice, we assume only one category of "failure," where a failed council member both signs incorrect data and fails to sign correct progress;

-

In Stage 0, the decision threshold for the security council is 4 out of 7; in Stage 1, it is 6 out of 8;

-

We assume a single unified proof system (as opposed to a 2/3 design where the security council breaks ties when the two disagree). Therefore, in Stage 2, the existence of the security council is irrelevant.

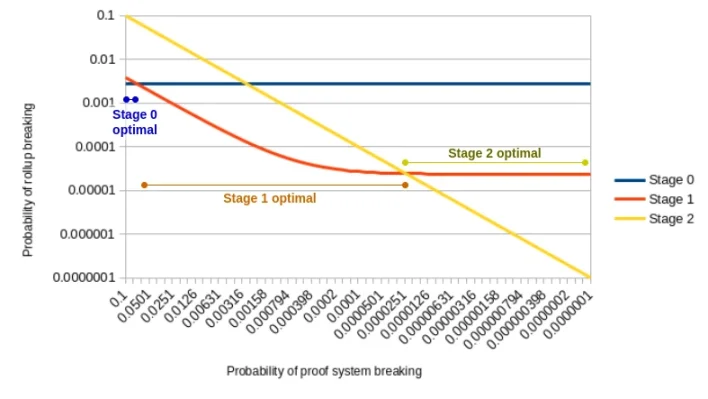

Under these assumptions, given a specific probability of proof system failure, we aim to minimize the likelihood of L2 network failure.

We can use the binomial distribution for this calculation:

-

If each security council member has a 10% independent failure chance, the probability that at least 4 out of 7 fail is ∑𝑖=4^7(7 𝑖)∗0.1^𝑖∗0.9^(7−𝑖)=0.002728. Thus, the integrated system in Stage 0 has a fixed failure probability of 0.2728%.

-

Stage 1 integration may also fail if the proof system fails and the security council’s validation mechanism suffers ≥3 failures, preventing network computation override (probability ∑𝑖=3^8(8 𝑖)∗0.1^𝑖∗0.9^(8−𝑖)=0.03809179 multiplied by the proof system failure rate), or if the security council itself suffers 6 or more failures, enabling it to forcibly generate an incorrect computation result (fixed probability ∑𝑖=6^8(8 𝑖)∗0.1^𝑖∗0.9^(8−𝑖)=0.00002341);

-

The failure probability of Stage 2 integration matches that of the proof system.

This is illustrated in the chart below:

Probability of proof system failure across different L2 network stages

As inferred above, as proof system quality improves, the optimal stage shifts from Stage 0 to Stage 1, and then from Stage 1 to Stage 2. Running a network at Stage 2 using a Stage 0-quality proof system yields the worst outcome.

Now, note that the assumptions in the above simplified model are imperfect:

-

In reality, security council members are not fully independent—they may suffer from "common-mode failures": they might collude, or all face the same coercion or hacking attempts, etc. The purpose of requiring a quorum-blocking subset outside the main organization is to mitigate this, but it remains imperfect.

-

The proof system itself might consist of multiple independent subsystems (as I previously advocated in my blog). In such cases, (i) the probability of proof system failure becomes extremely low, and (ii) even in Stage 2, the security council remains important as it serves as the key dispute resolver.

Both arguments suggest that Stages 1 and 2 are more attractive than the chart indicates.

If you trust the math, the justification for ever remaining in Stage 1 almost never holds—you should go straight to Stage 1. The main objection I hear is: if a critical bug occurs, it might be difficult to quickly obtain signatures from 6 out of 8 security council members to fix it. But there is a simple solution: grant any single council member the authority to delay withdrawals for 1 to 2 weeks, giving others sufficient time to take corrective action.

At the same time, however, jumping prematurely into Stage 2 is also wrong, especially if the transition effort comes at the expense of strengthening the underlying proof system. Ideally, data providers like L2Beat should display proof system audit and maturity metrics (preferably at the proof system implementation level rather than the entire rollup, so they can be reused), along with associated stage indicators.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News