MonadBFT Analysis (Part 1): How to Solve the Tail Forking Problem

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

MonadBFT Analysis (Part 1): How to Solve the Tail Forking Problem

The tail fork distorts the economic incentives for block proposers and poses a potential threat to network liveness. MonadBFT ensures that any block proposed by an honest leader and receiving a quorum of votes will not be abandoned or skipped, through the introduction of a re-proposal mechanism and No-Endorsement Certificates (NEC).

The core of blockchain lies in achieving a strict global consensus: regardless of where network nodes are located or which time zone they're in, all participants must ultimately agree on a single set of objective outcomes.

But real-world distributed networks are far from ideal: nodes go offline, some lie, and others deliberately cause disruptions. Under such conditions, how does the system still manage to "speak with one voice" and maintain consistency?

This is exactly what consensus protocols aim to solve. At their core, they are sets of rules that guide a group of independent—and even partially untrusted—nodes to reach unified decisions on the order and content of every transaction.

Once this "strict consensus" is established, blockchains can unlock key features such as digital property rights protection, inflation-resistant monetary models, and scalable social coordination structures. But this hinges on the consensus protocol itself guaranteeing two fundamental properties:

- No two conflicting blocks should ever both be confirmed;

- The network must keep progressing forward without getting stuck or halting.

MonadBFT represents the latest technical breakthrough toward achieving these goals.

A Brief Review of Consensus Protocol Evolution

The field of consensus mechanisms has been studied for decades. Early protocols like PBFT (Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance) were already capable of handling very realistic scenarios: even if some nodes fail, act maliciously, or send false messages, the system can still achieve consensus—as long as faulty nodes remain below one-third of the total.

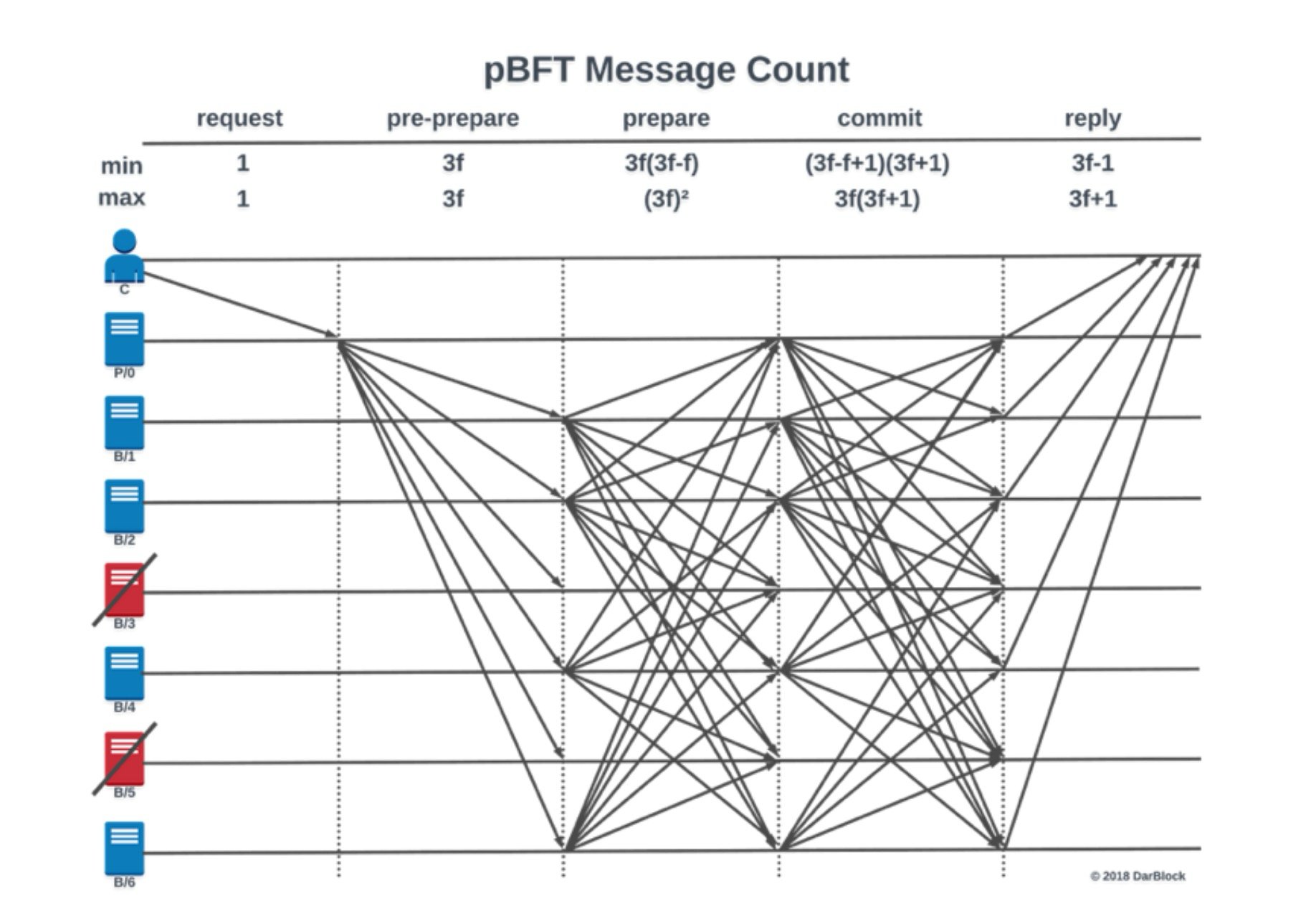

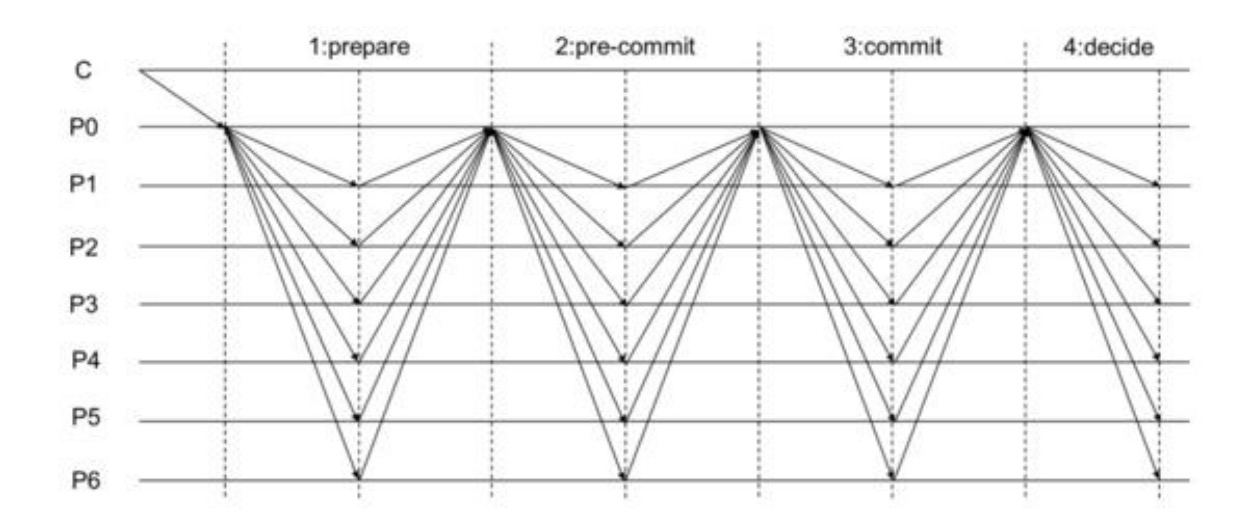

These early designs followed a relatively "traditional" approach: each round elects a leader who proposes a block, while other validators engage in multiple rounds of voting to confirm the transaction order step by step.

The entire voting process typically involves several phases—pre-prepare, prepare, commit, reply. In each phase, all validators must communicate with each other. In other words, everyone has to talk to everyone else, causing message volume to explode in a mesh-like pattern.

This communication structure has quadratic complexity, n²—meaning that with 100 validators, each consensus round could generate nearly 10,000 messages.

This isn't a big problem in small networks, but as the number of validators grows, the communication burden quickly becomes unsustainable, drastically reducing efficiency.

This "everyone talks to everyone" quadratic communication model is highly inefficient. For example, in a network of 100 validators, each consensus round may require handling tens of thousands of messages.

This might be manageable within a small closed group, but in a global, open-chain network, the communication load quickly becomes unacceptable. As a result, early BFT protocols like PBFT and Tendermint are typically limited to permissioned networks or systems with very few validators to remain functional.

To make BFT protocols viable in permissionless, public chain environments, newer designs have shifted toward lighter communication models: each validator communicates only with the leader, rather than exchanging messages with all peers.

This reduces message complexity from n² down to n—significantly easing system burden.

The HotStuff protocol, introduced in 2018, was designed specifically to address this scalability issue. Its design goal was clear: replace PBFT's complex voting flow with a simpler, leader-driven communication structure.

HotStuff’s key innovation is linear communication. In its mechanism, each validator sends their vote only to the current leader, who then aggregates these votes into a Quorum Certificate (QC), a cryptographic proof representing majority agreement.

This QC acts as a collective signature, proving to the entire network: "Most nodes have agreed on this proposal."

In contrast to PBFT’s "broadcast to all" model—where everyone speaks at once, creating chaos—HotStuff operates more like "one collects, one packages." No matter how large the network, it remains efficient.

Beyond linear communication, HotStuff can be further enhanced into a pipelined version (pipelined HotStuff) to boost efficiency.

In basic HotStuff, the same validator often serves as leader across multiple rounds until a block is fully confirmed. This follows a "one block per round" model, focusing all effort on advancing just one block at a time.

In pipelined HotStuff, the mechanism becomes more flexible: a new leader is elected each round, and each leader has two responsibilities:

- Collect votes from the previous round and package them into a Quorum Certificate (QC), broadcasting it to the network;

- Propose a new block, preparing for the next round.

In other words, instead of waiting to fully confirm one block before starting the next, it works like an assembly line, with different leaders handling different stages. The previous leader proposes a block; the next confirms it and proposes a new one—the consensus process passes like a baton in a relay race.

This is where the term "pipeline" comes from: while one block is still being confirmed, the next is already being prepared. Multiple steps proceed in parallel, increasing throughput.

To summarize, protocols like HotStuff represent major improvements over traditional BFT in two dimensions:

- Lighter communication: each validator only needs to communicate with the leader;

- Higher processing efficiency: multiple block confirmation processes can run concurrently.

This has made HotStuff a foundational design template for many modern PoS blockchain consensus mechanisms. However, every advantage comes with trade-offs—the pipelined structure, while high-performing, quietly introduces a subtle structural risk.

Next, we’ll dive deep into this critical issue: tail forking.

Tail Forking

While HotStuff—especially its pipelined version—solves the scalability challenges of consensus protocols, it also introduces new issues. The most critical and easily overlooked is known as "tail forking."

What is tail forking? Simply put, it's an unexpected block reorganization (reorg) occurring at the "tip" of the blockchain.

Specifically, there is a valid block that has been successfully propagated to most validators and received sufficient votes. It appears ready to be confirmed and written into the main chain—but in the end, it gets skipped, orphaned, and replaced by another block at the same height.

This isn’t a bug or an attack. Rather, it stems from a structural possibility inherent in the protocol design. That sounds unfair—so how does it happen?

As mentioned earlier, each leader in pipelined HotStuff has two tasks:

- A. Propose a new block (e.g., Bₙ₊₁)

- B. Collect votes for the previous leader’s block and generate a QC (e.g., finalize Bₙ)

These tasks proceed in parallel, passing responsibilities like a relay. But here lies the problem.

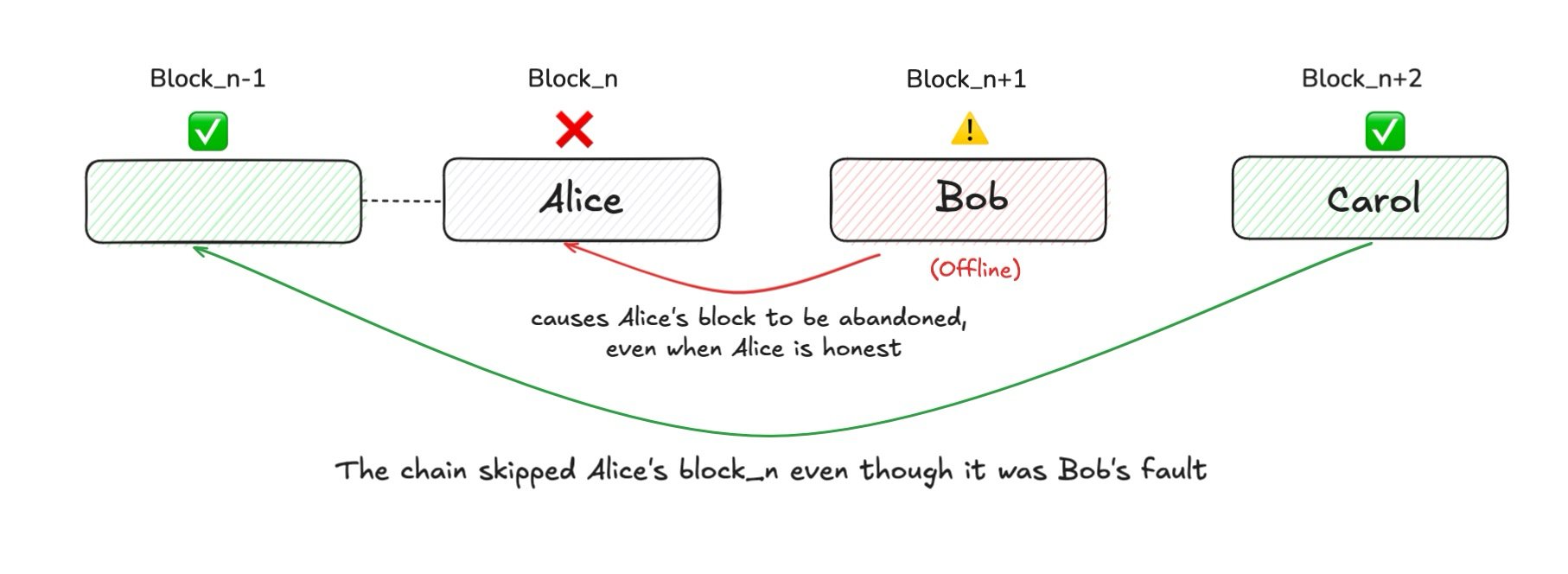

For example, suppose Alice is the leader and proposes block Bₙ at height n. This block receives a supermajority of votes and is "almost confirmed." Then Bob becomes the next leader, responsible for proposing Bₙ₊₁ and including the QC for Bₙ in his proposal to finalize it.

But if Bob goes offline—or intentionally fails to include Bₙ’s QC—then a problem arises.

Since no one completes the QC packaging for Alice’s block, the voting record for Bₙ never propagates. The block, which should have been confirmed, is effectively "cold-shouldered" and eventually ignored by the network.

This is the essence of tail forking: a prior leader’s block gets skipped due to the next leader’s failure or malice.

Why Is Tail Forking Serious?

Tail forking causes problems in two main areas: 1) broken incentives, and 2) threats to system liveness.

First, rewards are lost: If a block is discarded, its proposer receives no reward—neither block reward nor transaction fees. For instance, Alice proposes a valid block and secures a supermajority of votes, but due to Bob’s mistake or malicious action, the block isn’t confirmed, leaving Alice with zero compensation. This creates flawed incentive structures: malicious nodes like Bob can suppress competitors’ rewards simply by skipping their blocks—no technical attack required, just deliberate non-cooperation. If this happens repeatedly, participation and fairness decline over time, potentially encouraging collusion among nodes.

Second, expanded MEV attack surface: Tail forking enables a more subtle but serious issue—the manipulation of MEV (Maximum Extractable Value). For example, suppose Alice’s block contains a high-value arbitrage transaction. Bob, if colluding with the next leader Carol, can deliberately withhold propagation of Alice’s block. Carol then constructs a new block at the same height, copying Alice’s arbitrage transaction and claiming the MEV for herself. This "chain tip reordering + collusion" appears compliant on the surface but is actually a carefully orchestrated theft. Worse, it incentivizes leaders to form collusive relationships, turning block confirmation into a profit-sharing game rather than a public service.

Third, compromised finality and user experience: Compared to Nakamoto-style protocols, BFT’s key advantage is deterministic finality—once a block is committed, it cannot be reverted. Tail forking undermines this guarantee, especially for blocks that have received votes but not yet formal confirmation. High-throughput dapps often rely on reading data immediately after a block receives votes to reduce latency. If such a block is suddenly dropped, user states may roll back—such as account balances reverting, leveraged trades disappearing, or game states resetting unexpectedly.

Fourth, potential for cascading failures: Normally, tail forking might only delay a block by one round, with limited impact. But in edge cases, if multiple consecutive leaders choose to skip the prior block, the system could stall—no one is willing to "pick up" the previous block. The entire chain halts until a leader finally steps up to assume responsibility, allowing progress to resume.

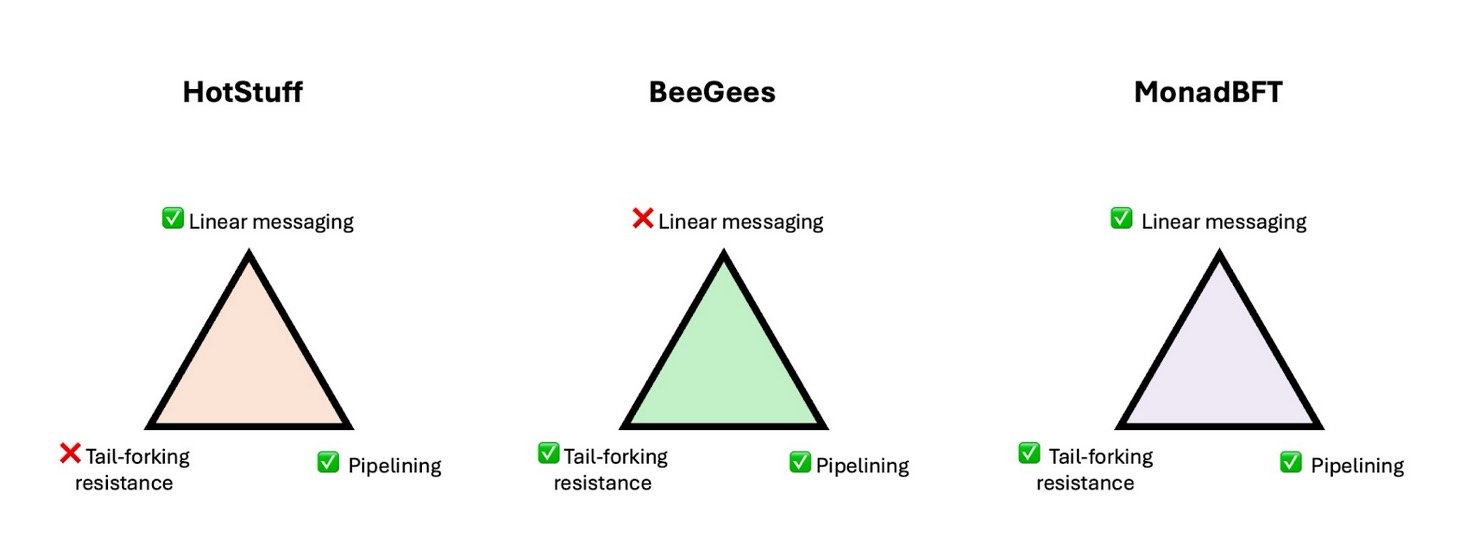

Although some prior solutions exist—such as the tail-forking avoidance mechanism in the BeeGees protocol—they often sacrifice performance, for example by reintroducing quadratic communication complexity, making the trade-off unfavorable.

What Is MonadBFT?

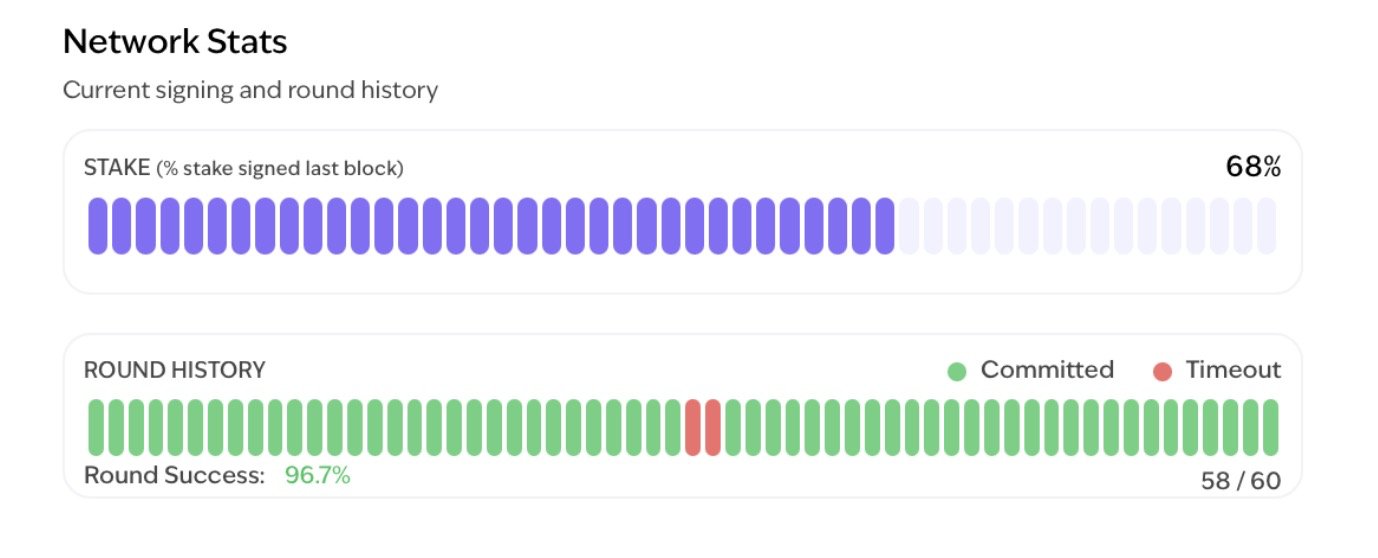

MonadBFT is a next-generation consensus protocol specifically designed to solve the tail-forking problem. Its breakthrough lies in eliminating structural vulnerabilities without sacrificing the performance benefits of pipelined HotStuff. In other words, MonadBFT doesn’t start from scratch—it builds upon HotStuff’s core framework and refines it. It retains three key features:

- Rotating leader: a new leader is elected each round to advance the chain;

- Pipelined commits: multiple block confirmation processes can overlap;

- Linear messaging: each validator only communicates with the leader, significantly reducing network overhead.

However, these three alone aren’t enough for full security. To close the structural gap left by tail forking, MonadBFT adds two critical mechanisms:

- Re-proposal mechanism

- No-Endorsement Certificate (NEC)

Re-Proposal Mechanism

In BFT protocols, time is divided into rounds (called views), with one leader per view responsible for proposing a new block. If the leader fails—for example, by not proposing a block on time or submitting an invalid proposal—the system switches to the next view and elects a new leader.

MonadBFT introduces a mechanism ensuring that during view changes, any honestly proposed block won’t be lost simply due to leader rotation.

When the current leader fails, validators send signed view-change messages indicating the current view has timed out.

Critically, these messages don’t just say "timeout"—they must also include the block the validator last voted for, effectively stating: "I didn’t receive a valid proposal; this is the latest block I’ve seen."

The new leader collects these timeout messages from a supermajority (2f+1) of validators and combines them into a Timeout Certificate (TC). This TC represents the network’s collective snapshot of the "head block" when the previous view failed. The new leader selects the highest block (or latest view) from this set—the so-called high_tip.

MonadBFT requires that the new leader’s proposal must include a valid TC and must re-propose the highest pending block from the TC, giving it another chance to be confirmed.

Why? As previously noted—we don’t want a nearly confirmed block to disappear.

For example, suppose Alice is the leader in view 5 and proposes a valid block that receives majority votes. Then Bob, the view 6 leader, goes offline and fails to advance the chain. When Carol becomes the view 7 leader, under MonadBFT rules, she must include the TC and re-propose Alice’s block—ensuring Alice’s honest work isn’t wasted.

If Carol doesn’t have Alice’s block, she can request it from other nodes. Nodes can either:

- Provide the block, or

- Return a signed "No-Endorsement" (NE) message, indicating they don’t have the block (mechanism detailed later). (At most f Byzantine nodes may ignore requests.)

Once Carol re-proposes Alice’s block, she gains an additional proposal opportunity, ensuring she isn’t penalized for the prior leader’s failure.

The purpose of the re-proposal mechanism is clear: to ensure fair chain progression, so no valid contribution is silently discarded due to bad luck or sabotage.

No-Endorsement Certificate (NEC)

Continuing the example: after Bob’s view times out, Carol requests the high_tip block (Alice’s block) from other validators. At least 2f+1 validators will respond:

- Either by providing Alice’s block,

- Or by sending a signed NE message stating they did not receive it.

If Carol receives Alice’s block, she must re-propose it according to protocol. Only if she receives NE signatures from at least f+1 validators can she skip the block and propose a new one.

Why f+1? In a BFT system with 3f+1 validators, at most f can be malicious. If Alice’s block truly received a supermajority of votes, at least 2f+1 honest nodes must have received it.

Therefore, if Carol claims "I can’t obtain Alice’s block," she must present signatures from f+1 validators proving they didn’t receive it. This forms a No-Endorsement Certificate (NEC).

The NEC serves as the leader’s免责 (exculpatory) evidence—a verifiable proof that the prior block wasn’t ready for confirmation, showing the skip wasn’t malicious but justified.

Re-Proposal + NEC = Solving Tail Forking

By introducing the Re-Proposal mechanism and the No-Endorsement Certificate (NEC), MonadBFT establishes a rigorous and explicit rule set for handling chain tips:

Either finalize the submission of a "nearly confirmed" block, or provide sufficient evidence proving it isn’t ready for confirmation. Otherwise, skipping or replacing the prior block is not allowed.

This mechanism ensures that any block receiving a quorum of votes cannot be abandoned due to leader failure or intentional evasion. The structural risk of tail forking is systematically eliminated, and the protocol imposes clear constraints on improper skipping behavior.

If a leader attempts to skip the prior block without justification and fails to provide an NEC, the protocol immediately detects and rejects the action. Any jump without cryptographic proof is treated as invalid and will not gain network consensus.

From an economic incentive perspective, this design provides clear protection for validators:

- Any block honestly proposed and supported by votes will retain its rewards, even if subsequent steps fail;

- Even in extreme cases—such as a node deliberately skipping their own proposal round to help another seize MEV from a prior block—the protocol forces the next leader to prioritize re-proposing the original block, preventing attackers from gaining economic benefit through skipping.

More importantly, MonadBFT achieves this enhanced security without sacrificing performance.

Some prior approaches to tail forking—like the BeeGees protocol—offer partial protection but often rely on high communication complexity (n²) or trigger expensive re-communication in every round, significantly increasing system load in practice.

MonadBFT’s design is more elegant:

Additional communication (e.g., timeout messages, block re-proposal) is triggered only when a view fails or anomalies occur. Under normal conditions—with honest leaders producing blocks consecutively—the protocol remains lightweight and efficient.

This dynamic balance between performance and security is one of MonadBFT’s core advantages over previous protocols.

Summary

This article reviewed the basic mechanics of traditional PBFT consensus, traced the evolution of the HotStuff protocol, and focused on how MonadBFT structurally addresses the inherent tail-forking problem in pipelined HotStuff.

Tail forking distorts proposer incentives and poses potential threats to network liveness. MonadBFT resolves this by introducing the re-proposal mechanism and the No-Endorsement Certificate (NEC), ensuring that any block proposed by an honest leader and backed by a quorum of votes will not be abandoned or skipped.

In the next part, we will explore two additional core features of MonadBFT:

- Speculative Finality

- Optimistic Responsiveness

And further analyze their practical implications for validators and developers.

To be continued.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News