Vitalik's new article: How are AI and crypto changing privacy?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik's new article: How are AI and crypto changing privacy?

Privacy is freedom.

Author: Vitalik Buterin, Ethereum co-founder

Translation: Baishui, Jinse Finance

Special thanks to Balvi volunteers Paul Dylan-Ennis, pcaversaccio, vectorized, Bruce Xu, and Luozhu Zhang for discussions and feedback.

Recently, I've become increasingly focused on improving the privacy landscape within the Ethereum ecosystem. Privacy is a critical safeguard for decentralization: whoever controls information holds power, so we must avoid centralized control over data. In the real world, concerns about centralized technological infrastructure often center not only on fears that operators might arbitrarily change rules or deplatform users, but equally on fears of data collection. While the cryptocurrency space originated from projects like Chaum's Ecash, which prioritized digital financial privacy, it has recently undervalued privacy—ultimately because of poor reasoning: before ZK-SNARKs existed, we couldn't provide privacy in a decentralized way, so we downplayed its importance and instead focused on other guarantees we could offer at the time.

However, today privacy can no longer be ignored. Artificial intelligence is dramatically enhancing the capabilities of centralized data collection and analysis, while simultaneously expanding the scope of data we voluntarily share. In the future, emerging technologies such as brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) will bring even greater challenges—we may indeed face AI systems capable of reading our thoughts. At the same time, we now possess far more powerful tools than the cypherpunks of the 1990s could have imagined to protect privacy, especially in digital domains: efficient zero-knowledge proofs (ZK-SNARKs) allow us to prove trustworthiness without revealing identity; fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) enables computation on data without viewing it; and obfuscation techniques may soon unlock further capabilities.

Privacy does not mean isolation—it means solidarity.

Now is an appropriate time to revisit this question: why do we need privacy? Everyone’s answer differs. In this article, I will present my own perspective, divided into three parts:

-

Privacy as freedom: Privacy gives us space to live according to our own needs, without constantly worrying how our actions will be perceived across various political and social games.

-

Privacy as order: Many fundamental mechanisms underpinning societal operations rely on privacy to function properly.

-

Privacy as progress: If we can discover new ways to selectively share information while protecting against misuse, we can unlock immense value and accelerate technological and social advancement.

Privacy Is Freedom

In the early 2000s, views similar to those summarized in David Brin’s 1998 book *The Transparent Society* were popular: technology would make information globally more transparent. Although this would bring downsides requiring constant adaptation, it was overall seen as highly positive—and fairness could be enhanced by ensuring people could monitor (or more precisely, surveil) governments. In 1999, Sun Microsystems CEO Scott McNealy famously declared: "Privacy is dead—get over it!" This mindset was widespread during Facebook’s early conception and development, when pseudonymous identities were prohibited. I personally recall experiencing the tail end of this attitude in 2015 at a Huawei event in Shenzhen, where a (Western) speaker casually repeated “privacy is dead.”

*The Transparent Society* represented the best and brightest vision that the “privacy is dead” ideology could offer: a promise of a better, fairer, more just world, using transparency to hold governments accountable rather than suppress individuals and minorities. However, in hindsight, even this vision was clearly a product of its time—written at the peak of global cooperation, peace, and enthusiasm for the “end of history”—and it relied on overly optimistic assumptions about human nature:

-

The upper echelons of global politics are generally benevolent and rational, making vertical privacy (withholding information from powerful entities) increasingly unnecessary. Abuses of power tend to be localized, so exposing them to sunlight is the best remedy.

-

Culture will continuously progress until horizontal privacy (withholding information from peers) becomes unnecessary. Nerds, gays, and eventually everyone else won’t need to hide in closets, because society will become more open and accepting of individual traits.

Today, no major country broadly accepts the first assumption as valid, and several widely regard it as false. On the second front, cultural tolerance is rapidly regressing—simply searching Twitter for phrases like “bullying is good” provides evidence, though many others are easily found.

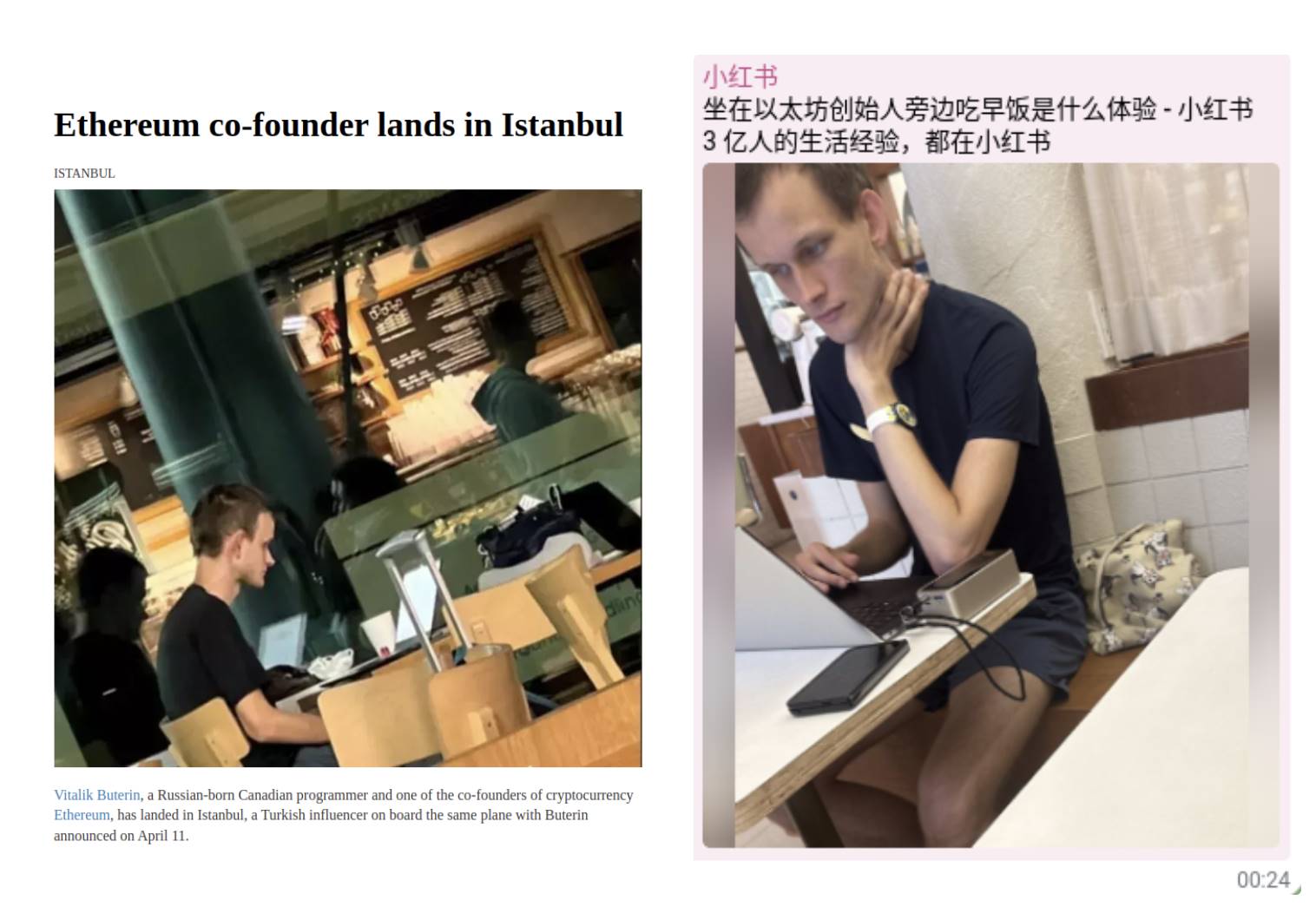

I’ve unfortunately experienced the downsides of the “transparent society” frequently, as nearly every move I make in public risks becoming a media spectacle:

Worst of all, someone filmed me using my laptop in Chiang Mai for one minute and posted it on Xiaohongshu, instantly gaining thousands of likes and shares. Of course, my situation is far from typical—but privacy has always been this way: people living relatively normal lives need less privacy, while those whose lives deviate from the norm require more, regardless of direction. Once you sum up all significant dimensions, the number of people who genuinely need privacy becomes substantial—and you never know when you might become one of them. This is also a key reason privacy is often underestimated: it’s not just about your current circumstances and information, but about unknowns regarding what might happen to that information in the future (and how it might affect you).

Today, even among AI advocates, privacy around corporate pricing mechanisms remains a niche concern. But with the rise of AI-powered analytics, it may become increasingly problematic: the more a company knows about you, the more likely they are to offer personalized prices, maximizing profit potential multiplied by your willingness to pay.

I can summarize my general argument for privacy as freedom in one sentence:

Privacy allows you to freely live in the way that best suits your personal goals and needs, without constantly balancing every action between your private game (your own needs) and public game (how various others—including through social media cascades, commercial incentives, politics, institutions, etc.—will perceive and respond to your behavior).

Without privacy, everything becomes a continuous struggle centered on “how will others (and robots) interpret what I’m doing”—whether powerful individuals, corporations, or peers, whether today or in the future. With privacy, we maintain balance. Today, this balance is rapidly eroding, especially in the physical realm. The default trajectory of modern tech capitalism—driven by business models that extract value from users without explicit payment—is further undermining this equilibrium (and may eventually penetrate deeply sensitive domains, including our own minds). Therefore, we must counteract this trend by more explicitly supporting privacy, particularly in areas where we can most practically achieve it: the digital domain.

But Why Not Allow Government Backdoors?

A common response to the above reasoning goes like this: the privacy harms I describe stem largely from excessive public knowledge of our private lives, and even abuses stem primarily from corporations, employers, and politicians knowing too much. But we wouldn’t let the public, corporations, employers, or politicians access all this data. Instead, we’d allow a small group of well-trained, rigorously vetted law enforcement professionals to view data from street surveillance cameras, internet cables, and chat app wiretaps—under strict accountability procedures—so no one else finds out.

This is a quietly widespread position, making it crucial to address explicitly. Even when implemented with good intentions and high standards, such strategies have inherent instabilities due to the following reasons:

-

Not just governments, but numerous corporate entities face data breach risks, with varying levels of security. In traditional finance, KYC and payment data reside with payment processors, banks, and various intermediaries. Email providers access vast quantities of user data. Telecom companies track your location and regularly resell it illegally. Overall, regulating all these entities strictly enough to ensure genuine respect for user data demands enormous effort from both surveillors and the surveilled—and may conflict with maintaining competitive free markets.

-

Individuals with access inevitably face temptations to misuse data (including selling to third parties). In 2019, several Twitter employees were charged and later convicted for selling dissidents’ personal information to Saudi Arabia.

-

Data is always vulnerable to hacking. In 2024, data legally collected by U.S. telecom companies was breached, allegedly by hackers linked to the Chinese government. In 2025, Ukraine’s government-held sensitive personal data was hacked by Russian actors. Conversely, highly sensitive Chinese government and corporate databases have also been hacked—including by the U.S. government.

-

Regimes may change. A government trusted today may not be tomorrow. Those in power today may be persecuted tomorrow. A police force upholding impeccable standards today could descend into cruel misconduct within a decade.

From an individual’s perspective, if their data is stolen, they cannot predict whether or how it might be misused in the future. To date, the safest approach to handling large-scale data is minimizing centralized collection from the outset. Data should remain maximally under users’ control, with useful statistics aggregated via cryptographic methods that preserve individual privacy.

The argument that governments should retain warrant-based access to any information—because this is how things have always worked—ignores a key point: historically, the volume of information accessible via warrants was far smaller than today, and even smaller than what could be obtained under the strictest possible internet privacy protections. In the 19th century, the average person had voice conversations that were never recorded by anyone. Thus, moral panics about “information privacy” contradict historical norms: completely unconditional secrecy of ordinary conversations and even financial transactions was the millennia-long default.

An ordinary conversation in 1950. Aside from the participants during the conversation, no one ever recorded, monitored, “lawfully intercepted,” analyzed with AI, or otherwise accessed it at any time.

Another important reason to minimize centralized data collection is that much of global communication and economic interaction is inherently international. If everyone lived in the same country, one could at least argue that “the government” should have access to interaction data. But what if people are in different countries? In principle, you might attempt a “galaxy-brain” solution mapping each person’s data to a responsible legal authority—though even then, complex multi-party edge cases arise. But even if feasible, this isn’t the realistic default. The actual default outcome of government backdoors is data centralization in a few key jurisdictions controlling applications—and thus holding everyone’s data: de facto global tech hegemony. Strong privacy is by far the most stable alternative.

Privacy Is Order

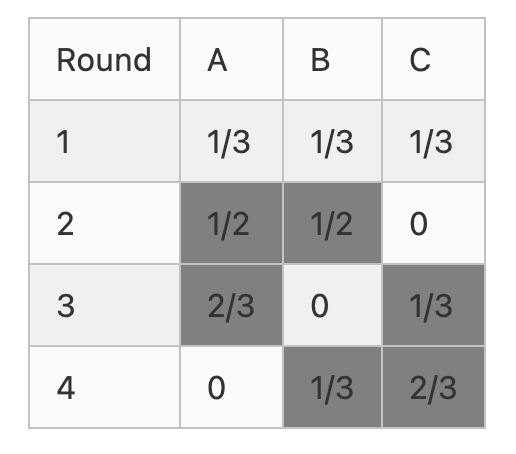

For over a century, it has been recognized that a key technical component enabling effective democratic systems is secret ballot: no one knows who you voted for, and crucially, even if you wanted to prove it, you couldn’t. Without secret ballots as the default, voters face various side incentives influencing their choices: bribes, retrospective rewards, social pressure, threats, and so on.

A simple mathematical argument shows how such side incentives can completely undermine democracy: in an election with N participants, your chance of affecting the outcome is roughly 1/N, so any consideration about which candidate is better gets divided by N. Meanwhile, side games (e.g., voter bribery, coercion, social pressure) directly impact you based on your vote—not the overall result—so they aren’t divided by N. Thus, unless side games are strictly controlled, they will default to overwhelming the entire process, drowning out any discussion about which candidate’s policies are actually superior.

This applies not only to national-scale democracy. In theory, it affects nearly all principal-agent problems in enterprises or governments:

-

Judges deciding case rulings

-

Government officials selecting contractors or grant recipients

-

Immigration officers issuing or denying visas

-

Social media company staff enforcing content moderation policies

-

Company employees involved in business decisions (e.g., supplier selection)

The core problem in all cases is identical: if agents act honestly, they generate only a small fraction of the benefit for the entity they represent; but if they follow side-game incentives, they capture the full benefit themselves. Hence, even today, we rely heavily on moral goodwill to prevent our institutions from collapsing into chaotic mutual subversion via proliferating side games. If privacy weakens further, these side games grow stronger, and the required level of moral goodwill may become unrealistically high.

Can social systems be redesigned to avoid this issue? Unfortunately, game theory almost definitively says no (except in one case: complete dictatorship). In non-cooperative game theory—where each participant makes independent decisions and coordinated group action is disallowed—mechanism designers enjoy great freedom to “engineer” games toward specific outcomes. Indeed, mathematical proofs show every game must have at least one stable Nash equilibrium, making such analyses tractable. But in cooperative game theory—which allows coalition formation (“collusion”)—we can prove many games lack any stable outcome (called a “core”). In such games, no matter the current state, some coalition can always profitably deviate.

If we take mathematics seriously, we conclude that the only way to build stable social structures is by limiting the extent of coordination possible among participants—meaning high privacy (including deniability). If we disregard mathematics itself, observing the real world—or simply imagining how the above principal-agent scenarios would collapse under side-game dominance—leads to the same conclusion.

Note that this reveals another risk of government backdoors. If everyone had unlimited ability to coordinate with others on everything, the result would be chaos. But if only a few can do so—due to privileged information access—the result is their dominance. One party having backdoor access to another’s communications easily implies the end of viable multiparty systems.

Another key example of social order relying on limited collusion is knowledge and cultural activities. Participation in intellectual and cultural life is inherently a public good driven by intrinsic motivation: external incentives aimed at benefiting society are hard to design precisely because such activities partly define what counts as socially beneficial behavior. We can create approximate commercial and social incentives to guide things in the right direction, but they require strong supplementation by intrinsic motivation. Yet this also makes such activities highly vulnerable to imbalances in external motivations, especially side games like social pressure and coercion. To limit the influence of such distorting external motives, privacy again becomes essential.

Privacy Is Progress

Imagine a world without public-key or symmetric-key cryptography. In such a world, securely sending messages over long distances would be fundamentally harder—not impossible, but very difficult. International collaboration would decrease significantly, forcing more cooperation to remain offline and face-to-face. The world would become poorer and more unequal.

I believe we are currently in exactly such a situation relative to a hypothetical future world where more advanced forms of cryptography—especially programmable cryptography—are widely adopted, supported by stronger full-stack security and formal verification to ensure correct usage.

Egyptian God Protocol: Three powerful and highly versatile constructs enabling computation on data while keeping it fully private.

Healthcare is a prime example. Anyone who has worked in longevity, pandemic response, or other health fields over the past decade will tell you that future treatments and prevention will be personalized, with effectiveness heavily dependent on high-quality data—including personal and environmental data. Effectively protecting people from airborne diseases requires knowing which areas have higher or lower air quality and where pathogens appear at specific times. Leading longevity clinics already offer customized recommendations and therapies based on your body, dietary preferences, and lifestyle data.

Yet all this simultaneously poses massive privacy risks. I personally know of an incident where a company gave an employee a home air monitor, and the collected data was sufficient to determine when the employee engaged in sexual activity. For similar reasons, I expect much of the most valuable data will remain uncollected by default, due to fear of privacy risks. Even when collected, such data is almost never widely shared or provided to researchers—partly for commercial reasons, but equally due to privacy concerns.

The same pattern repeats across other domains. Our documents, messages sent across apps, and social media behaviors contain vast information about ourselves that could improve predictions and delivery of daily necessities. Additionally, there's abundant data unrelated to healthcare about how we interact with the physical environment. Today, we lack tools to effectively use this information without creating dystopian privacy nightmares. But in the future, we may possess such tools.

The best way to address these challenges is strong cryptography that lets us gain benefits from shared data without the downsides. In the AI era, the need for data—including personal data—will only grow more important. The ability to locally train and run “digital twins” that make decisions based on high-fidelity approximations of our preferences will deliver immense value. Ultimately, this may involve brain-computer interface (BCI) technologies capturing high-bandwidth inputs from our brains. To avoid resulting in highly centralized global dominance, we must find ways to achieve this while respecting privacy. Programmable cryptography is the most trustworthy solution.

My AirValent air quality monitor. Imagine a device that collects air quality data, publishes aggregated statistics on an open-data map, and rewards you for contributing—all using programmable cryptography to avoid leaking your personal location while verifying data authenticity.

Privacy Can Advance Social Safety

Programmable cryptography, such as zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs), is extremely powerful because it acts like LEGO bricks for information flows. It enables fine-grained control over who sees what information—and more importantly, what information can be revealed. For instance, I can prove I hold a Canadian passport showing I’m over 18, without disclosing any other personal details.

This enables many interesting combinations. Here are a few examples:

-

Zero-knowledge proof-of-personhood: Prove you are a unique human (via various ID forms: passports, biometrics, decentralized social graph attestations) without revealing additional identity information. Useful for “prove you’re not a bot,” “one person, max N” use cases, etc., while fully preserving privacy unless rules are violated.

-

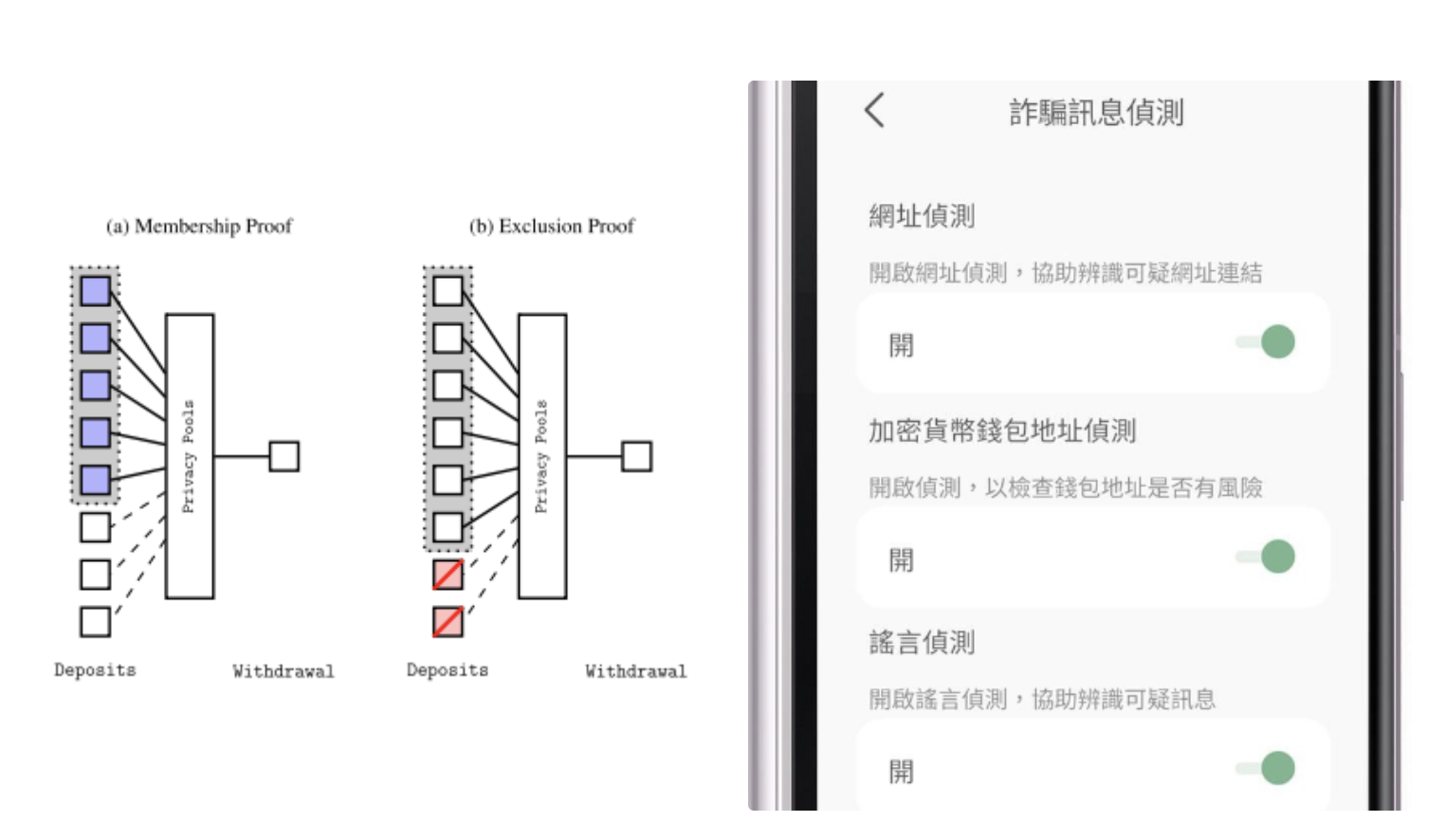

Privacy Pools: A financial privacy solution that excludes bad actors without backdoors. Users can prove their tokens weren’t sourced from publicly known hacker or theft lists during spending; only hackers and thieves themselves cannot generate such proofs, so they remain exposed. Railgun and privacypools.com currently implement such schemes.

-

On-device anti-fraud scanning: Doesn’t rely on ZKPs but fits conceptually. Use built-in device filters (including LLMs) to scan incoming messages and automatically detect misinformation and scams. When performed on-device, user privacy remains intact and operates via user permission, allowing individuals to choose which filters to subscribe to.

-

Provenance tracking for physical goods: Combine blockchain and zero-knowledge proofs to trace item attributes throughout manufacturing chains. For example, this could price environmental externalities without publicly disclosing supply chain details.

Left: Privacy Pool diagram. Right: Message Checker app, where users can toggle multiple filters—URL check, cryptocurrency address check, rumor check—from top to bottom.

Privacy and Artificial Intelligence

Recently, ChatGPT announced it would begin incorporating your past conversations into AI context for future interactions. This trend will inevitably continue: AI reviewing your past dialogues to extract insights is fundamentally useful. Soon, we may see AI products that invade privacy even more deeply: passively collecting your web browsing patterns, emails, chat logs, biometric data, and more.

Theoretically, your data is private to you. But in practice, it often doesn’t seem that way:

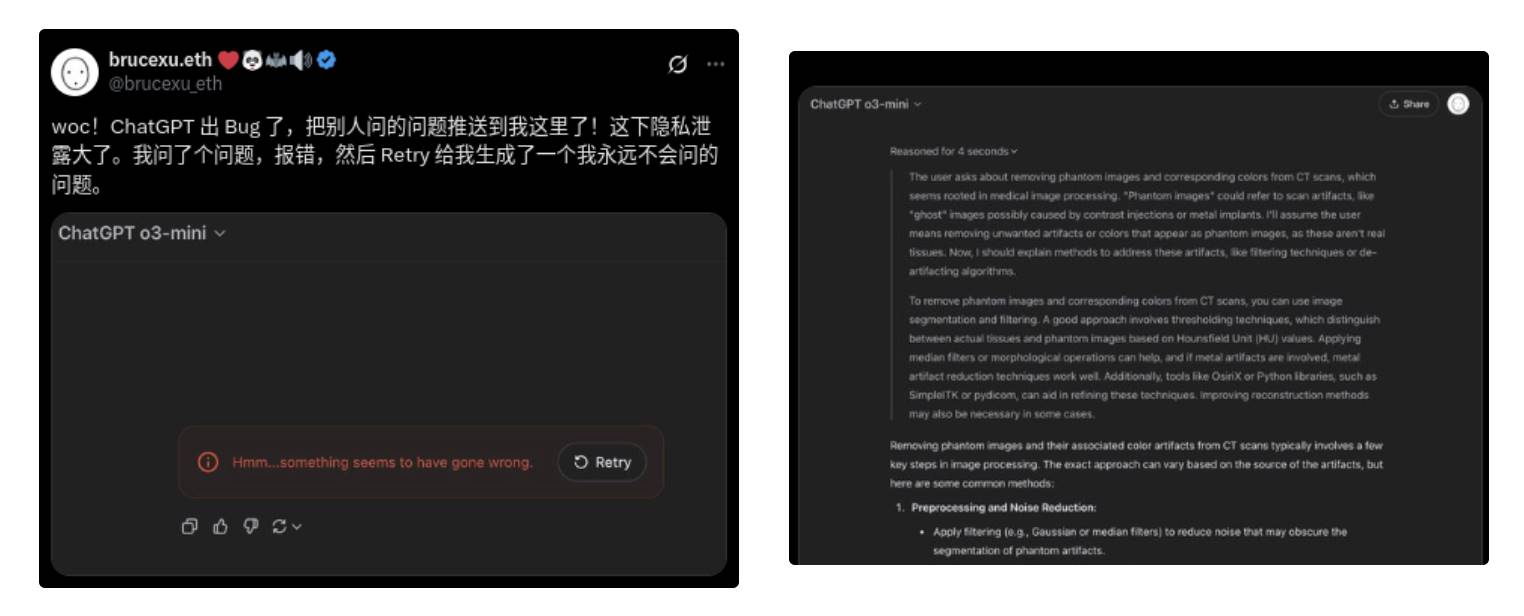

Wow! ChatGPT has a bug—it pushed someone else’s questions to me! Serious privacy leak. I asked a question, got an error, then 'retry' generated a question I'd never ask.

It's possible the privacy mechanism worked perfectly and the AI merely hallucinated, generating and answering a question Bruce never asked. But currently, this cannot be verified. Similarly, we cannot verify whether our conversations are used for training.

All of this is deeply concerning. More troubling are explicit surveillance use cases of AI that massively collect and analyze users’ (physical and digital) data without consent. Facial recognition is already helping authoritarian regimes suppress political dissent at scale. Most alarming is the ultimate frontier of AI data collection and analysis: the human mind.

Theoretically, brain-computer interface (BCI) technology holds astonishing potential to enhance human capabilities. Consider last year’s story of Neuralink’s first patient, Noland Arbaugh:

This experimental device restored a sense of independence to the 30-year-old Arbaugh. Previously, using a mouth stick required someone to keep him upright. If the stick fell, someone had to retrieve it. He couldn’t use it for long periods without developing sores. With the Neuralink device, he gained near-complete computer control. He can browse the web and play computer games anytime, and Neuralink claims he set the record for human BCI cursor control speed.

Today, these devices are powerful enough to help injured patients. In the future, they may empower fully healthy individuals to collaborate with computers and communicate telepathically with unimaginable efficiency (!!). But truly decoding brain signals to enable such communication requires artificial intelligence.

These trends intertwined could naturally lead to a dark future: silicon-based super-agents consuming and analyzing everyone’s information—including writing, behavior, and thought patterns. But an alternative, brighter future exists: enjoying the benefits of these technologies while preserving our privacy.

This can be achieved by combining several technologies:

-

Run computations locally whenever possible—many tasks (e.g., basic image analysis, translation, transcription, fundamental EEG analysis for BCIs) are simple enough to be fully handled on local devices. In fact, local computation offers advantages in reduced latency and verifiability. If something can be done locally, it should be. This includes intermediate steps involving internet access or logging into social media accounts.

-

Use cryptography to make remote computation fully private—Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) enables AI computations on remote servers without exposing data or results. Historically, FHE was prohibitively expensive, but (i) its efficiency is rapidly improving, and (ii) LLMs involve uniquely structured computations dominated asymptotically by linear operations—making them ideal for ultra-efficient FHE implementations. Computations involving multiple parties’ private data can use Multi-Party Computation (MPC); common two-party cases can be handled extremely efficiently via techniques like garbled circuits.

-

Use hardware verification to extend guarantees into the physical world—we can demand that hardware capable of reading our thoughts (whether implanted or external) must be open and verifiable, using technologies like IRIS for validation. We can apply this elsewhere: for example, installing security cameras that provably save and forward video streams only when a local LLM flags physical violence or medical emergencies, deleting footage otherwise—and subjecting them to community-driven random audits via IRIS to verify correct implementation.

The Imperfect Future

In 2008, libertarian philosopher David Friedman wrote a book titled *The Machinery of Freedom*, later expanded into *The Imperfect Future*. In it, he outlined how new technologies might transform society—not always favorably (or positively). In one section, he described a potential future where complex interactions between privacy and surveillance emerge: growth in digital privacy offsets increasing real-world surveillance:

If a video mosquito sits on the wall watching me type, strong encryption for my emails becomes meaningless. Thus, in a transparent society, strong privacy requires some way to protect the interface between my physical body and cyberspace... A low-tech solution is typing under a hood. A high-tech solution involves creating a connection between mind and machine that bypasses fingers—or any channel visible to external observers.

The tension between physical transparency and digital privacy also operates in reverse... My handheld device encrypts my message with your public key and transmits it to your device, which decrypts and displays it via your VR glasses. To prevent shoulder-surfing, the goggles don’t display images on screens but use micro-lasers to write directly onto your retinas. Hopefully, the inside of your eyeballs remains private space.

We might end up in a world where bodily activities are fully public, yet information exchanges are fully private. It has appealing features. Ordinary citizens could still leverage strong privacy to hire assassins, but the cost may exceed affordability, since in a sufficiently transparent world, all murders get solved. Every assassin lands in jail after completing a job.

How do these technologies interact with data processing? On one hand, modern data processing makes transparent societies threatening—if you record everything happening worldwide, it’s useless without processing, because no one could find the six inches of tape they want amid millions of miles produced daily. On the other hand, technologies enabling strong privacy offer renewed possibilities for reclaiming privacy—even in worlds with modern data processing—by protecting transactional information from being accessed by anyone.

Such a world might be the best of all possible worlds: if things go well, we’ll see a future with almost no physical violence, while preserving our digital freedoms and ensuring the basic functioning of political, civic, cultural, and intellectual processes—processes that depend on some limitation on total informational transparency.

Even if imperfect, it’s far better than versions where physical and digital privacy approach zero—including eventually the privacy of our own thoughts. By the mid-2050s, we may see opinion pieces arguing that expecting thoughts to remain free from lawful interception is unrealistic. Responses to such articles would link to recent incidents: an AI company’s LLM exploited, leaking 30 million people’s private inner monologues across the internet within a year.

Society has always depended on a balance between privacy and transparency. In certain cases, I also support limiting privacy. As an example entirely different from usual arguments on this topic, I support the U.S. government’s move to ban non-compete clauses in contracts—not primarily because of direct impacts on employees, but because it forces companies to partially open-source tacit domain knowledge. Forcing firms to be more open than they wish limits privacy—but I see this as a net-positive restriction. Yet macroscopically, the most urgent technological risk in the near future is that privacy will hit historic lows in a highly unbalanced way: the most powerful individuals and dominant nations gaining massive access to everyone’s data, while others see almost nothing. Therefore, supporting privacy for everyone and making necessary tools open-source, universal, reliable, and secure is one of the defining challenges of our era.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News