David Luan, Early OpenAI Employee, in Latest Interview: DeepSeek Hasn't Changed the AI Technology Narrative

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

David Luan, Early OpenAI Employee, in Latest Interview: DeepSeek Hasn't Changed the AI Technology Narrative

Achieving more intelligence at lower costs does not mean you will stop pursuing intelligence.

Author: MD

Produced by: Mingliang Company

Recently on Redpoint Ventures' podcast "Unsupervised Learning," Redpoint partner Jacob Effron interviewed David Luan. They discussed from a technical perspective the implications DeepSeek has brought to research and practice in the large model field, sharing insights into current bottlenecks in AI models and potential breakthrough directions.

David Luan is an early employee of OpenAI. After graduating from Yale in 2009, he first joined iRobot working on robotics, then worked at several companies (including Microsoft), before joining the still-early-stage OpenAI in 2017 when its research team had only 35 people. In this interview, he mentioned that his reason for joining an AI company stemmed from his interest in robotics, believing that "the biggest limitation of robots lies in the intelligence level of underlying algorithms."

In 2020, David Luan left OpenAI and joined Google, but didn't stay long—he co-founded Adept with two colleagues he met during his time there, serving as CEO. Last August, he joined Amazon as head of the AGI San Francisco Lab.

Below is the translated transcript of the interview compiled by Mingliang Company (slightly edited):

Limits of Large Models and the Value of Reinforcement Learning

Jacob: David Luan leads Amazon's AGI Lab. Previously, he was co-founder and CEO of Adept, which raised over $400 million to develop AI Agents. He served as VP of Engineering at OpenAI, contributing to many key breakthroughs. I'm Jacob Effron.

Today on the show, David and I explore many interesting topics—his views on DeepSeek, predictions about future model advancements, the state of Agents and how to make them reliable, and when they'll become ubiquitous. He also shares some fascinating stories about OpenAI’s early days and its unique culture. This is a particularly fun conversation because David and I have known each other for over a decade. I think listeners will really enjoy it. David, thanks for joining our podcast.

David: Thanks for having me. This will be great—we’ve known each other for over ten years.

Jacob: I remember when you first joined OpenAI—I thought it seemed interesting, but wasn’t sure if it was a smart career move. Then clearly, you always see opportunities earlier than others.

David: I was very lucky because I've always been interested in robotics, and back then, the biggest limitation of robotics was the intelligence level of underlying algorithms. So I started working in artificial intelligence, seeing these technologies advance within our lifetime—it's truly exciting.

Jacob: Today I want to discuss many things with you. Let's start with a recent hot topic. Obviously, there's been a huge reaction to DeepSeek in the past few weeks. People are talking about it nonstop; stocks plummeted. Some say it's bad news for OpenAI and Anthropic. I feel like emotions have calmed down since the initial panic. But I’m curious—what do people get right or wrong about the impact of this event in broader discussions?

David: I still remember that morning when everyone was focused on DeepSeek news. When I woke up and checked my phone, there were five missed calls. I thought, what happened? The last time this occurred was during SVB’s collapse, when all investors called asking me to pull funds from SVB and First Republic Bank. So I figured something terrible must have happened. I checked the news and found stocks dropped due to the release of DeepSeek R1. I immediately realized people completely misunderstood this. What DeepSeek did was excellent, but it's part of a broader narrative—first we learn how to make new large models smarter, then we figure out how to make them more efficient.

So this is actually a turning point. Where people go wrong is thinking just because you can achieve more intelligence at lower cost means you’ll stop pursuing intelligence. Quite the opposite—you use even more intelligence. Once the market realizes this, we return to rationality.

Jacob: Given that base models appear to be trained based on OpenAI’s work, you can make base DeepSeek models behave like ChatGPT in various ways. Looking ahead, due to knowledge distillation, will OpenAI and Anthropic stop openly releasing these models?

David: What I think will happen is people always want to build the smartest models, but sometimes those models aren't always inference-efficient. So I expect we’ll increasingly see, even if not openly discussed, massive “teacher models” being trained internally in labs using all available compute resources. Then efforts will focus on compressing them into efficient models suitable for customers.

The biggest issue I see now is imagining AI use cases as concentric circles of complexity. The innermost layer might be simple chat conversations with basic language models, which GPT-2 already handled well. Each added layer of intelligence—like mental arithmetic, programming, later Agents, or even drug discovery—requires smarter models. But every prior level of intelligence becomes so cheap it can be quantized (reducing numerical precision to lower resource consumption).

Jacob: That brings me to the trend of test-time compute. It seems like a very exciting path forward, especially in verifiable domains like programming and math. How far can this paradigm take us?

David: There's a series of papers and podcasts documenting my long-standing thoughts on building AGI (Artificial General Intelligence).

Jacob: Let's add something new to those discussions.

David: Now we can prove we're having this conversation today. But back in 2020, when we began seeing GPT-2 emerge, GPT-3 may have already been in development or completed. We started thinking about GPT-4, living in a world where people weren't sure whether predicting the next token alone could solve all AGI problems.

My view—and that of some around me—is “no.” The reason is, if a model is trained on next-token prediction, it's essentially penalized for discovering new knowledge, since that knowledge isn’t in the training set. Therefore, we need to look at other known machine learning paradigms capable of truly discovering new knowledge. We know reinforcement learning (RL) can do this; RL does it in search, right? Yes, or like AlphaGo, which may have first shown the public that we can use RL to discover new knowledge. The question has always been, when will we combine large language models (LLMs) with RL to build systems that possess all human knowledge and can build upon it?

Jacob: For domains harder to verify, like healthcare or law, can this test-time compute paradigm enable models to handle such tasks? Or will we become extremely good at programming and math, yet still fail to tell a joke?

David: That’s debatable, but I have a very clear opinion.

Jacob: What’s your answer?

David: These models generalize better than you think. Everyone says, “I used GPT-1, it seemed better at math, but when waiting for it to think, maybe slightly worse than ChatGPT or other models.” I think these are just minor bumps on the road to much stronger capabilities. Today, we’re already seeing signs that explicitly verifying whether a model correctly solved a problem (as seen in DeepSeek) indeed enables transfer to slightly fuzzier problems in similar areas. I believe everyone is trying hard—my team and others—to address human preference challenges in more complex tasks to satisfy those preferences.

Jacob: Yes. And you always need to build a model that can verify outputs like “this is good legal advice” or “this is a solid medical diagnosis,” which is clearly much harder than checking if a math proof or code runs correctly.

David: I think what we’re leveraging is the gap between a model’s ability to judge whether it did a good job versus its ability to generate correct answers—same neural network weights. We consistently observe these models are stronger at judging whether they “did a good job” than at generating good answers. To some extent, we leverage this via certain RL techniques so the model develops an internal sense of whether it did something well.

Jacob: What research problems need solving to truly launch such models?

David: So many problems—I might only list three. First, I think the main challenge is knowing how to build an organization and process to reliably produce models.

I always tell my team and collaborators, today, if you run a modern AI lab, your job isn’t building models—it’s building a factory that reliably produces models. When you think this way, it completely changes your investment direction. Until reproducibility is achieved, I don’t think much progress occurs. We’ve just transitioned from alchemy to industrialization—the way models are built has changed. Without this foundation, models simply won’t work.

I think the next part is you must go slow to go fast. But I believe this comes first. I always believed people are drawn to algorithms because they seem cool and sexy. But if we examine what truly drives progress, it’s engineering. For example, how do you perform large-scale cluster computing ensuring reliable long-running operations? If one node crashes, you shouldn’t waste too much time on your task. Pushing the frontier of scale is a real challenge.

Now, across the entire reinforcement learning (RL) field, we’re rapidly approaching a world with many data centers, each performing massive inference on base models, perhaps testing in new environments brought by customers to learn how to improve models, feeding this new knowledge back centrally so models learn to become smarter.

Jacob: People like Yann LeCun have recently criticized the limitations of large language models (LLMs). I’d like you to summarize this criticism for our audience, then share your thoughts on those who claim these models can never achieve true original thinking.

David: I think we already have counterexamples—AlphaGo demonstrated original thinking. If you recall early OpenAI work, we used RL to play Flash games—if you’re from that era, you might remember MiniClip and similar games. These were once middle-school pastimes, but seeing them become foundations of AI was fascinating. We studied how to use our algorithms to beat these games simultaneously, and quickly discovered they learned to speed-run by exploiting glitches like walking through walls—things humans never did.

Jacob: On verification, it's mainly about finding clever ways to verify across different domains.

David: You just use the model.

How to Build Reliable Agents

Jacob: I’d like to shift to the world of Agents. How would you describe the current state of these models?

David: I remain incredibly excited about Agents. It reminds me of 2020–2021 when the first wave of truly powerful models like GPT-4 emerged. Trying them gave a strong sense of potential—they could write great rap songs, deliver sharp roasts, and handle basic three-digit addition. But when you asked it to “help me order a pizza,” it merely mimicked Domino’s customer service dialogue patterns, unable to complete actual tasks. This clearly exposed a major flaw in these systems, right?

Since then, I’ve firmly believed Agent issues must be solved. While at Google, we began researching what later became known as “tool use”—how to expose action interfaces to large language models (LLM) so they autonomously decide when to act. Though academia called them “Agents,” the public lacked unified understanding. We tried coining “Large Action Model” instead of “Large Language Model”, sparking some discussion. But eventually the industry settled on “Agent,” a term now so overused it’s lost its meaning—a shame, but it was cool being the first modern Asian company exploring this space.

When we founded Adept, the best open-source LLMs performed poorly. Since multimodal LLMs (like image-input models such as later GPT-4v) didn’t exist, we had to train our own model from scratch—we had to do everything ourselves, akin to starting an internet company in 2000 and needing to call TSMC to manufacture your own chips. It was insane.

So along the way, we learned that without today’s RL techniques, large language models are essentially behavioral cloners—they do what they saw in training data, meaning once they encounter unseen situations, their generalization suffers and behavior becomes unpredictable. So Adept has always focused on useful intelligence. What does usefulness mean? Not launching flashy demos that go viral on Twitter. Rather, putting these technologies into people’s hands so knowledge workers no longer need to do tedious tasks like dragging files on computers. Knowledge workers care about reliability. So one early use case was: Can we help people process invoices?

Jacob: Everyone loves processing invoices (laughs). For general-purpose models, this seems a natural starting point.

David: It’s a great “Hello World.” At the time, no one had really done this—we picked an obvious “Hello World” use case. We did Excel and other projects. If a system deletes a third of your QuickBooks entries once every seven times, you’ll never use it again. Reliability remains an issue—even today, systems like Operator are very impressive, seemingly outperforming other cloud computer Agents. But looking at both, they focus on end-to-end task execution, e.g., inputting “find me 55 weekend getaway spots,” and attempting to complete it. But end-to-end reliability is very low, requiring significant human intervention. We haven’t reached the point where enterprises can truly trust these systems to “set and forget.”

Jacob: We must solve this. Maybe explain to our audience what actually needs to be done to turn an existing base multimodal model into a Large Action Model?

David: I can discuss this at a high level, but essentially two things are needed. First is an engineering challenge—how to present available actions in a way the model can understand. For example, here are callable APIs, here are UI elements you can interact with. Let’s teach it a bit about how Expedia.com or SAP works. This involves research engineering. This is step one—giving it awareness of its capabilities and basic action skills.

The second part is where it gets interesting—how to teach it planning, reasoning, replanning, following user instructions, even inferring users’ true intentions and completing those tasks. This is a tough R&D challenge, vastly different from regular language modeling, where the goal is “generate some text,” even today’s reasoning tasks like math have a final answer.

So it’s more of a single-step process—even with multi-step thinking, it just gives you the answer. This is a fully multi-step decision-making process involving backtracking, predicting consequences of actions, realizing deleting might be dangerous—you must implement all this in basic setups.

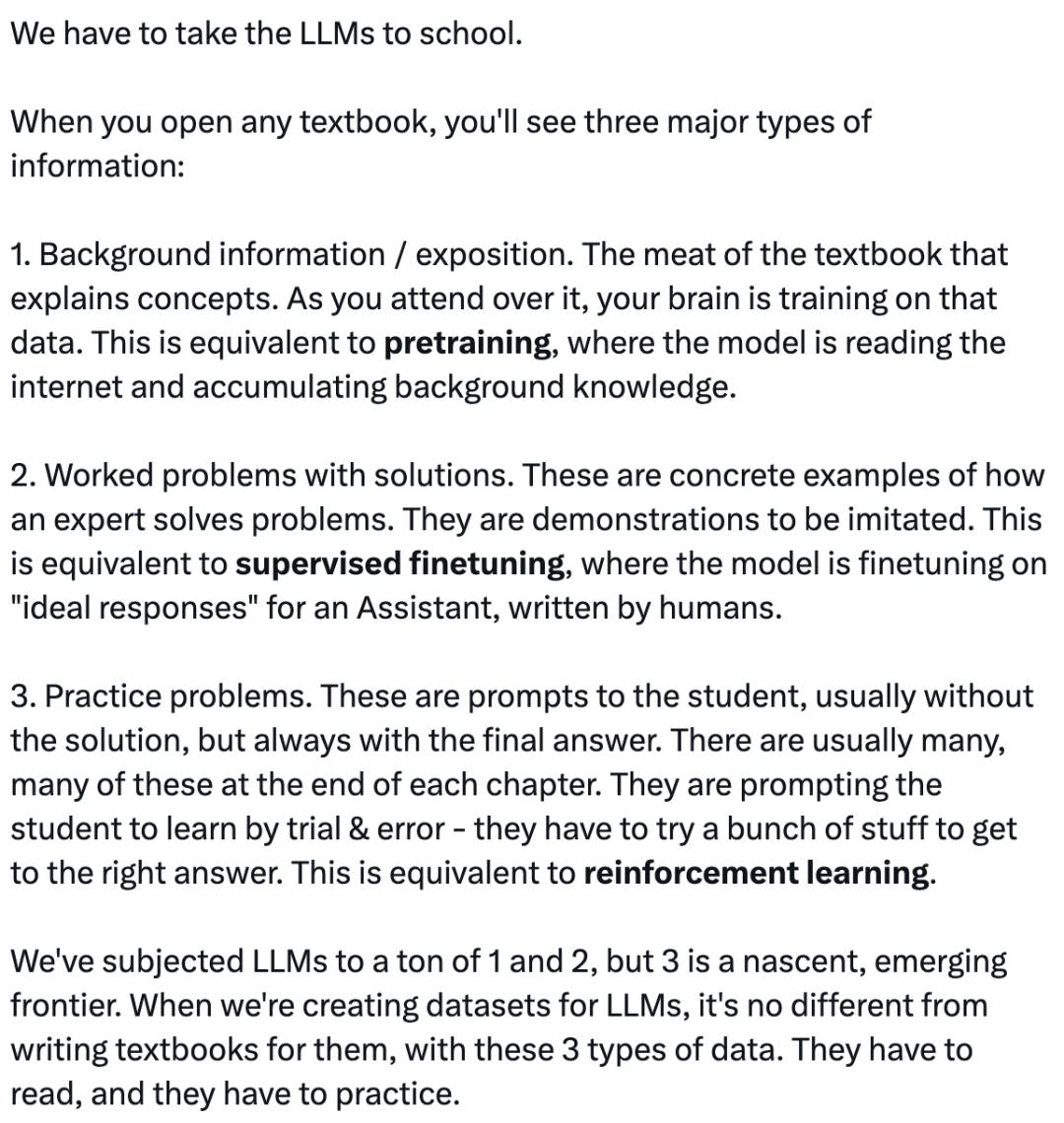

Then place it in sandboxed environments to learn under its own conditions. The best analogy is Andrej Karpathy saying modern AI training resembles textbook structure: first, full explanations of physical processes, then sample problems. The first part is pretraining, sample problems are supervised fine-tuning, and the final step is open-ended questions, maybe with answers in the back. We’re just following this process.

Andrej Karpathy's description of large models (Source: X.com, Mingliang Company)

Jacob: I’m sure you’ve deeply considered how these Agents truly enter the world. Let me ask a few questions. First, you mentioned part of the problem is letting models know what they can access. Over time, how will models interact with browsers and programs? Will it resemble human interaction? Or purely through code? Are there other methods?

David: Commenting on this field, I think the biggest current issue is lack of creativity in how people interact with increasingly intelligent large models and Agents. Remember when iPhone launched, App Store came out, people made all sorts of apps—press a button to burp, tilt phone to pour beer into mouth. Our interfaces today feel similarly poor, because chatting is a highly constrained, low-bandwidth interaction method, at least in certain aspects. For instance, I don’t want to go through seven rounds of dialogue to choose pizza toppings.

This lack of creativity frustrates me. I partly think it’s because talented product designers who could help solve these issues don’t yet fully grasp the models’ limitations. This is rapidly changing, but conversely, those pushing technical boundaries often treat it as “delivering a black box” rather than “delivering an experience.”

When this changes, I expect to see systems where interacting with an Agent synthesizes a multimodal UI listing what it needs from you, establishing shared context between human and AI—not today’s paradigm of mere chatting. It’s more like doing something together on a computer, watching the screen, more parallel than vertical.

Jacob: You mentioned Operator is impressive now but imperfect. When do you think we’ll have reliable intelligent Agents?

David: I think Operator is amazing, but currently the whole field lacks the final piece.

Jacob: Considering autonomous driving history, perhaps as early as 1995 they demonstrated cross-country self-driving, completing 99% of the journey.

David: Yes.

Jacob: Do we need another 30 years?

David: I don’t think so, because I believe we actually already have the right tools.

Jacob: You previously mentioned AGI isn’t actually far off.

David: My key milestone for Agents is I can give any task to this Agent during training, come back days later, and it’s 100% completed. Yes, like humans giving a 5% reliability boost, but the Agent has already learned how to solve it.

Jacob: As you noted, when founding Adept, there weren’t truly open models, let alone multimodal open ones. Do you think someone starting an Adept-like company today could succeed? Or will foundational model companies and hyperscale cloud providers ultimately drive progress?

David: I have significant uncertainty about this. But my current view is, personally, AGI isn’t actually far off.

Jacob: When you mention AGI, how do you define it?

David: One definition is a model capable of performing any useful human task on a computer—that’s part of it. Another definition I like is a model able to learn such tasks as quickly as humans. I don’t think these are far off, but I also don’t believe they’ll rapidly diffuse throughout society. As we know, per Amdahl’s Law, once you accelerate one thing, others become bottlenecks, limiting overall speedup.

So I think what will happen is we’ll possess the technology, but humanity’s ability to effectively use it will lag significantly. Many colleagues call this “capability overhang”—a massive surplus of capability.

Jacob: Have you done any preliminary thinking about potential acceleration factors once we have these capabilities?

David: It depends on people—about co-designing interactions with models and how to use them. It will be about social acceptance. Imagine a model emerges tomorrow claiming: “I invented a whole new way of doing things—everyone should adopt it.” Humans need to reconcile with it and decide if it’s truly a better solution—it won’t happen as fast as we imagine.

Jacob: As you said, even if labs first develop these models, there may be an opportunity for startups to bridge the gap between model capabilities and what end users actually want to interact with.

David: I’m basically certain this is what will happen. Because ultimately, I still firmly believe that in a world with AGI, human relationships matter deeply. Ultimately, understanding and owning customers, being closer to them and understanding their needs, will matter more than merely controlling a tool owned by many other labs.

Jacob: How do you think humans will use computers in the next ten years? All these models meet your definition of AGI. Will I still sit at a computer? What’s your vision for future human interaction with these technologies?

David: I think we’ll gain new toolkits for computer interaction. Today, some still use command lines, right? Like people still use GUIs. In the future, people will still use voice interfaces. But I think ambient computing will also grow. And I believe one metric we should watch is the leverage humans gain per unit energy spent interacting with computers. I think this metric will continue growing as these systems evolve.

Jacob: Maybe briefly discuss this future model world—will we end up with any domain-specific models?

David: Take a hypothetical legal expert model. You’d probably want it to know basic facts about the world.

Jacob: Many people get a general degree before law school.

David: Exactly. So I think there will be domain-specific models, but I don’t want to miss the point—just saying there will be some. I think there will be domain-specific models for technical reasons, but also for policy reasons.

Jacob: That’s interesting—what do you mean?

David: Some companies really don’t want their data mixed together. Imagine a large bank with sales & trading and investment banking divisions—AI employees or LLMs supporting these departments shouldn’t share information through weights, just like human employees today can’t share information.

Jacob: What else do you think needs solving? On the model side, you seem confident that scaling current compute power gets us close to solving needed problems. But are there other major technical hurdles to overcome to keep expanding model intelligence?

David: Actually, I disagree with the idea that simply porting existing tech to next-year’s compute clusters will magically make everything work. While scale remains important, my confidence comes from assessing core open problems—judging how hard they are to solve. For example, are there super-hard problems requiring disruptive innovation? Like replacing gradient descent entirely (note: gradient descent is the core algorithm optimizing deep learning model parameters by iteratively updating in the negative gradient direction of the loss function), or requiring quantum computers for AGI? But I don’t think these are necessary paths.

Jacob: When new models come out, how do you evaluate them? Do you have fixed test questions, or how do you judge their quality?

David: My evaluation methodology rests on two core principles: Methodological Simplicity: This is the most fascinating trait in deep learning—when a study includes methodology documentation (increasingly rare today), simply reviewing its implementation path may reveal a simpler, more effective solution than traditional approaches. Such breakthroughs often enter deep learning canon, creating moments of insight like “this truly shows the beauty of algorithms.”

Benchmark Misalignment: Hype in the field has led to numerous benchmarks misaligned with actual model needs, yet overly emphasized in R&D pipelines. These tests are essentially games. The complexity of evaluation and measurement is severely underestimated—deserving far greater academic recognition and resources compared to many current research directions.

Truly Differentiated Technical Accumulation Is Rare

Jacob: It seems everyone has internal benchmarks they don’t publicly release—things they trust more. Like seeing OpenAI’s models perform better on many programming benchmarks, yet everyone uses Anthropic’s models, knowing they’re better. Watching this field evolve is fascinating. I’d love to hear about your recent experiences at Amazon—how do you see Amazon’s role in the broader ecosystem?

David: Yes, Amazon is a very interesting place. Actually, I’ve learned a lot there. Amazon is deeply committed to building general intelligent systems, especially general intelligent Agents. I think what’s truly cool is that everyone at Amazon understands computation itself is shifting from familiar primitives to calling large models or large Agents—likely the most important computational primitive of the future. So people care deeply about this—it’s fantastic.

I find it interesting—I lead Amazon’s Agent business, and it’s cool to see how widely Agents touch a large company like Amazon. Peter and I opened a new research lab for Amazon in San Francisco, largely because many senior Amazon leaders genuinely believe we need new research breakthroughs to solve the main problems toward AGI we discussed earlier.

Jacob: Are you following any alternative architectures or more cutting-edge research areas?

David: Let me think. I always watch things that might help us better map model learning to computation. Can we use more computation more efficiently? This provides huge multiplicative effects on what we can do. But I actually spend more time on data centers and chips—I find it very interesting. There are some exciting moves happening now.

Jacob: Seemingly one of the main drivers advancing models is data labeling, and clearly all labs spend heavily here. In the test-time compute paradigm, is this still relevant? What’s your view?

David: Two data labeling tasks come to mind. First is teaching models foundational knowledge of how to complete tasks by cloning human behavior. With high-quality data, you can better elicit things the model already saw during pretraining. Second, teaching models what’s good vs bad for ambiguous tasks. I think both remain very important.…

Jacob: You’ve clearly been at the forefront of this field for the past decade. Is there one thing you changed your mind about in the past year?

David: I’ve been thinking about team culture. We always knew this, but I’ve become more convinced that hiring truly smart, energetic, intrinsically motivated people—especially early in their careers—is actually a key engine of our success. In this field, the optimal strategy shifts every few years. So if people are too adapted to previous optimal strategies, they actually slow you down. So compared to my prior thinking, betting on newcomers works better.

Another thing I changed my mind on: I once thought building AI would yield real long-term technical differentiation you could accumulate upon. I thought if you excelled at text modeling, it should naturally make you a winner in multimodal domains. If you succeeded in multimodal, you should dominate reasoning and Agent fields… These advantages should compound. But in practice, I see little accumulation. I think everyone tries similar ideas.

Jacob: Implying that just because you break through on A doesn’t guarantee advantage on B. For example, OpenAI broke through on language models, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll break through on reasoning.

David: They’re related, but it doesn’t mean you’ll automatically win the next opportunity.

When Will Robots Enter Homes?

Jacob: I want to ask—you originally entered AI through robotics. So, what’s your view on the current state of AI robotics?

David: Similar to my view on Digital Agents, I think we already have many raw materials. And interestingly, Digital Agents give us a chance to solve tricky problems before tackling physical Agents.

Jacob: Elaborate—how does reliability in digital Agents carry over to physical Agents?

David: A simple example: suppose you have a warehouse to reorganize and a physical Agent you ask to calculate the optimal rearrangement plan. Learning in the physical world, or even in robot simulators, is difficult. But if you’ve already done this in digital space, possessing all training recipes and algorithm tuning knowledge for learning from simulation data, it’s like you’ve already completed this task with training wheels.

Jacob: That’s interesting. I think when people think of robots, there are two extremes. Some believe the scaling laws discovered in language models will also appear in robotics, we’re on the brink of massive change. You often hear Jensen (NVIDIA founder Huang Renxun) talk about this. Others think it’s like 1995 autonomous vehicles—great demo, but long way to real functionality. Where on this spectrum do you stand?

David: Returning to what I mentioned earlier, what gives me the most confidence is our ability to build training recipes enabling 100% task completion. We can do this in digital space. Though challenging, it will eventually transfer to physical space.

Jacob: When will we have robots in homes?

David: I think this actually returns to what I mentioned earlier. I believe the bottleneck for many problems isn’t modeling, but diffusion of modeling.

Jacob: What about video models? Clearly many are entering this field—it seems a new frontier involving understanding world models and physics for more open exploration. Perhaps share what you’re seeing and your views.

David: I’m very excited. I think it solves a major problem we mentioned earlier—today we can make reinforcement learning work on problems with verifiers, like theorem proving.

Then we discussed extending this to Digital Agents, where you lack verifiers but may have reliable simulators—because I can launch a staging environment of an app and teach the agent how to use it. But the remaining big question is: what happens when there’s no explicit verifier or simulator? I think world modeling is our answer to this question.

OpenAI’s Organizational Growth Journey

Jacob: Great. I’d like to shift topics slightly and discuss OpenAI and your time there. Clearly, you participated in a very special period and played similar roles in many advances. I think in the future we’ll see many analyses of OpenAI’s culture—what made the era developing GPT-1 to GPT-4 so special? What will those analyses say? What made this organization so successful?

David: When I joined OpenAI, the research community was still very small. It was 2017, OpenAI had existed just over a year. I knew the founding team and some early members—they were looking for someone who could blur the line between research and engineering, which fit me perfectly.

Joining OpenAI was incredibly fortunate. The team had only 35 people, all exceptionally talented—many had done extensive supercomputing work and other achievements I could list individually. They were all outstanding members of that early team.

Interestingly, initially my role was helping OpenAI build scalable infrastructure, growing from a small team to larger scale. But quickly, my role shifted to defining a differentiated research strategy allowing us to make correct judgments in machine learning for this era. I think we realized earlier than others that the previous research model—writing a world-changing paper with your three best friends—was over. We needed to seriously consider this new era, using larger teams combining researchers and engineers to tackle major scientific goals, regardless of whether academia deemed the solution “novel.” We were willing to take responsibility. When GPT-2 first launched, people said it looked like a Transformer—“Yes, it’s a Transformer.” And we were proud of that.

Jacob: So why did you join OpenAI at the time?

David: I was extremely excited—I wanted to stand at the research frontier. The options then were OpenAI, DeepMind, or Google Brain. …As I mentioned earlier, betting on truly intrinsically motivated individuals, especially early in their careers, proved a very successful strategy—many defining figures at the time lacked PhDs or 10 years of experience.

Jacob: Did you notice common traits among these outstanding researchers? What made them excel? What did you learn about assembling them into teams to achieve goals?

David: Largely intrinsic motivation and intellectual flexibility. One person was deeply passionate and engaged in his research on our team—I won’t name him. About a month and a half later, I had a one-on-one with him—he suddenly mentioned he moved to the Bay Area to join us but hadn’t installed Wi-Fi or electricity in his apartment yet. He spent all his time in the office running experiments—this was completely unimportant to him.

Jacob: That kind of passion is truly impressive. I recall you mentioning Google didn’t capitalize on the GPT breakthrough despite inventing Transformers. At the time, the technology’s potential was obvious, but Google as a whole struggled to rally around it. What are your thoughts?

David: Credit goes to Ilya—he was our scientific leader in foundational research, later instrumental in GPT, CLIP, and DALL·E. I remember him frequently visiting offices, like a missionary telling people: “Hey, I think this paper matters.” He encouraged people to experiment with Transformers.

Jacob: With foundational model companies doing so much now, could another “recipe” emerge at some point?

David: I think losing focus is very dangerous.

Jacob: You’re probably one of NVIDIA and Jensen’s (Huang Renxun) biggest fans. Beyond widely known achievements, what do you think NVIDIA does that’s under-discussed but critically important?

David: I really admire Jensen—he’s a true legend. I think he made many correct decisions over a long period. The past few years have been a huge inflection point for NVIDIA—they internalized interconnect technology and chose to build businesses around systems, a very wise move.

Jacob: We usually end interviews with a quick Q&A. Do you think model progress this year will be more, less, or the same as last year?

David: On the surface, progress may seem similar, but it’s actually more.

Jacob: What do you think is overhyped or underappreciated in AI today?

David: Overhyped: “Skills are dead, we’re doomed, stop buying chips.” Underappreciated: how we’ll truly solve ultra-large-scale simulation problems so models can learn from them.

Jacob: David, this was a fantastic conversation. I believe people will want to learn more about your work at Amazon and the exciting things you’re doing—where can they find more information?

David: For Amazon, follow the Amazon SF AI Lab. I don’t use Twitter much, but I plan to restart. So follow my Twitter @jluan.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News