Vitalik's new article: Significantly expanding L1 still holds value and will make application development simpler and more secure

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik's new article: Significantly expanding L1 still holds value and will make application development simpler and more secure

The goal of this article is to argue that, regardless of whether more applications should run long-term on L1, scaling L1 by approximately 10x holds significant value.

Author: Vitalik Buterin

Translation: Daisy, MarsBit

An important short-term discussion in the Ethereum roadmap is how much the L1 gas limit should be increased. Recently, the L1 gas limit was raised from 30 million to 36 million, increasing network capacity by 20%. Many support further significant increases in the near future. These improvements are made possible by recent and upcoming technical advances, such as improved efficiency of Ethereum clients, EIP-4444 reducing historical data storage requirements (see roadmap), and future stateless client technologies.

However, before taking this step, we must consider a key question: in a rollup-centric roadmap, is raising the L1 gas limit the right choice in the long run? Increasing the gas limit is easy, but reducing it is extremely difficult—even if reduced later, the decentralization impact could be permanent. If excessive L1 usage brings centralization risks and we are uncertain whether such usage delivers sufficient benefits, that would be an undesirable outcome.

This article argues that even in a world where most users and applications run on L2, significantly expanding L1 still has value because it makes application development patterns simpler and more secure.

This article does not attempt to argue whether more applications should run on L1 in the long term. Instead, its goal is to show that regardless of the outcome of that debate, approximately 10x expansion of L1 has important long-term value.

Censorship Resistance

The goal is resistance to censorship

MarsBit Note: Text in the image originates from the novel "1984": "War is peace, freedom is slavery, ignorance is strength."

One of blockchain's core value propositions is censorship resistance: if a transaction is valid and the user can pay the market rate for gas, the transaction should be reliably and quickly included on-chain.

In some cases, censorship resistance needs to work on very short time scales. For example, users holding positions in DeFi protocols may face liquidation if market prices fluctuate rapidly, even with just a 5-minute delay in transaction inclusion.

The staker set on L1 is highly decentralized, making long-term transaction censorship extremely difficult—typically delaying transactions by only a few slots at most. There are also proposals to further strengthen Ethereum’s censorship resistance to ensure transactions can still be included even if block building becomes highly centralized and outsourced.

In contrast, L2s rely on relatively more centralized block producers or centralized sequencers, which can easily choose to censor specific user transactions. Some L2s (e.g., Optimism and Arbitrum; see their official documentation) offer force-inclusion mechanisms allowing users to submit transactions directly via L1. However, the practical feasibility of these mechanisms depends on two key factors:

1. L1 transaction fees must be low enough that users can afford to submit transactions directly on L1;

2. L1 must have sufficient block space so that even during widespread L2 censorship, L1 can accommodate user transactions submitted directly to bypass L2.

Therefore, increasing L1 capacity not only reduces fees but also enhances L2 users’ ability to respond when facing censorship, preserving blockchain’s core value—censorship resistance.

Basic Mathematical Assumptions

We can estimate the actual cost of using force-inclusion mechanisms through some calculations. First, list several assumptions that will be reused in other sections:

1. The current cost of an L1 → L2 deposit transaction is about 120,000 L1 gas. For example, one case on Optimism.

2. A minimal L1 operation, such as changing the value of a storage slot, costs 7,500 L1 gas (cold SSTORE plus calldata cost for the address, plus some computation).

3. ETH price is $2,500.

4. Gas price is 15 gwei, a reasonable long-term average approximation.

5. Demand elasticity is close to 1 (i.e., doubling gas limits halves prices). This has some support from previous data analysis, but in reality, actual elasticity may differ in either direction.

6. We want attack-response costs below $1. “Normal” operations should not exceed $0.05 per transaction. Intermediate exceptional operations (e.g., key changes) should be under $0.25. This is clearly an intuitive value judgment.

Based on these assumptions, the current cost to bypass censorship is: 120000 * 15 * 10**-9 * 2500 = $4.5

To bring this below target, we need to expand L1 by 4.5x (though note this is a very rough estimate, as elasticity is hard to measure and absolute usage levels are difficult to predict).

Transferring Assets Between L2s

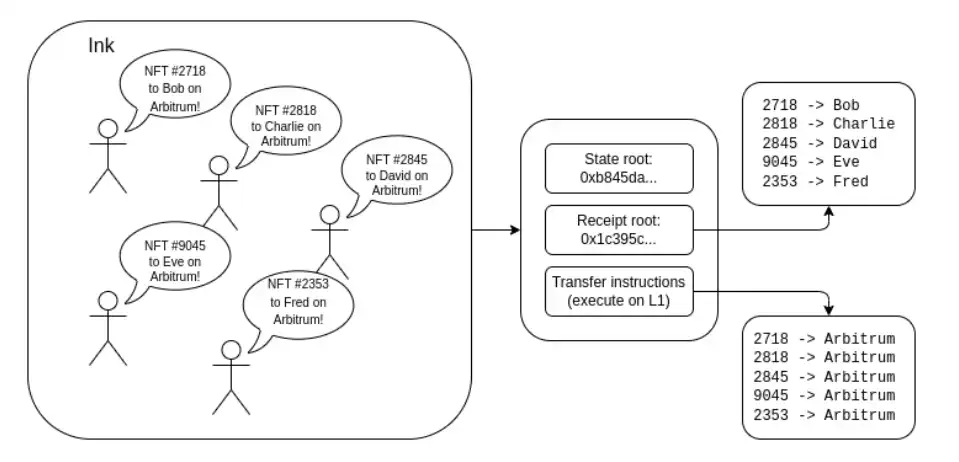

Users often need to transfer assets from one L2 to another. For common, high-volume assets, the most practical method is intent-based protocols (e.g., ERC-7683). In practice, only a few market makers need to directly transfer assets between two L2s; other users simply trade with them. However, for low-volume assets or NFTs, this approach is unfeasible, so individual users must use L1 transactions to move these assets between L2s.

Currently, withdrawal costs from an L2 are about 250,000 L1 gas, and deposit costs are 120,000 L1 gas. Theoretically, this process can be significantly optimized. For example, to transfer an NFT from Ink to Arbitrum, the base ownership of the NFT must be bridged from the Ink bridge to the Arbitrum bridge—a single L1 storage operation costing about 5,000 gas. Other operations are mostly calls and proofs, which—with suitable logic—can be kept very low; assume total cost is 7,500 gas.

Let’s calculate the costs in both scenarios.

Current situation: 370000 * 15 * 10**-9 * 2500 = $13.87

Ideal design: 7500 * 15 * 10**-9 * 2500 = $0.28

Our ideal target is $0.05, meaning L1 needs to scale by about 5.5x.

Alternatively, we can analyze directly based on capacity. Suppose each user on average performs one cross-L2 NFT (or rare ERC20) transfer per month. Ethereum’s monthly total gas capacity is: 18,000,000 × (12 × 30 × 86,400) = 3.88 trillion gas—enough to support 518 million such transfers. Thus, if Ethereum wants to serve global users (assuming Facebook’s user count of 3.1 billion), it would need to scale capacity by about 6x, considering this as the sole use case for L1.

L2 Mass Exits

A key feature of L2s is enabling users to exit to L1 in case of failure—a capability lacking in alt-L1s. What happens if all users cannot successfully exit within a week? For optimistic rollups, this may not be a major issue: as long as one honest participant exists, they can prevent confirmation of malicious state roots. However, in Plasma systems, if data becomes unavailable, exits typically need to happen within one week. Even in optimistic rollups, if there is a hostile governance upgrade, users have a 30-day window to withdraw assets (see: Phase 2 definition).

What does this mean? Suppose a Plasma chain fails and exit costs are 120,000 gas. How many users can exit within a week? Calculation: 86400 * 7 / 12 * 18000000 / 120000 = 7.56 million users.

For an optimistic rollup with a hostile 30-day-delay governance upgrade, the number increases to 32.4 million users. Assume a mass exit protocol allows many users to exit simultaneously. If we push efficiency to the limit—each user only requires one SSTORE and minor computation (i.e., 7,500 gas)—the numbers rise to 121 million and 518 million users respectively.

Sony recently launched an L2 on Ethereum; PlayStation has around 116 million monthly active users. If all became Soneium users, current Ethereum couldn’t scale sufficiently to support a mass exit event. However, with smarter mass exit protocols, it could barely cope.

If we wish to avoid technically complex hash-commitment protocols, we might reserve 7,500 gas per asset. I have 9 high-value assets in my main Arbitrum wallet; using this as an estimate, L1 might need to scale by about 9x.

Another user concern is that even if L1 scaling is safe, they may lose substantial funds due to extremely high gas costs.

Let’s analyze exit gas costs, comparing existing and “ideal” exit costs:

Existing: 120000 * 15 * 10**-9 * 2500 = $4.5

Ideal: 7500 * 15 * 10**-9 * 2500 = $0.28

However, the problem with these estimates is that during mass exits, everyone tries to exit simultaneously, so gas costs rise significantly. We’ve already seen days where average daily L1 gas prices exceeded 100 gwei. Using 100 gwei as a baseline, withdrawal cost becomes $1.88, meaning L1 needs to scale 1.9x to keep exits affordable (below $1). Additionally, if you want users to exit all assets at once without using complex hash-commitment protocols, each asset may require 7,500 gas, increasing withdrawal costs to $2.5 or $16.8 depending on parameters—thus requiring corresponding L1 scaling to keep costs bearable.

Issuing ERC20 Tokens on L1

Today, many tokens are issued on L2s. But this introduces an underestimated security risk: if an L2 undergoes a hostile governance upgrade, ERC20 tokens issued on it could begin minting new tokens indefinitely, with no way to stop these tokens from spreading across the ecosystem. If tokens are issued on L1, the damage from a rogue L2 remains largely confined to that L2.

To date, over 200,000 ERC20 tokens have been issued on L1. Supporting even 100 times that number is feasible. However, to make issuing ERC20 tokens on L1 a popular choice, costs must be low enough. Take Railgun token (a major privacy protocol) as an example. Its deployment transaction cost 16,470 gas, about $61.76 under our assumptions—acceptable for companies. In principle, this cost can be greatly reduced, especially for projects issuing many tokens with identical logic. Yet even reducing cost to 120,000 gas keeps it at $4.5.

If our goal is bringing Polymarket to L1 (at least asset issuance; trading can remain on L2), and we want many micro-markets, then aiming for $0.25 per operation means L1 would need to scale approximately 18x.

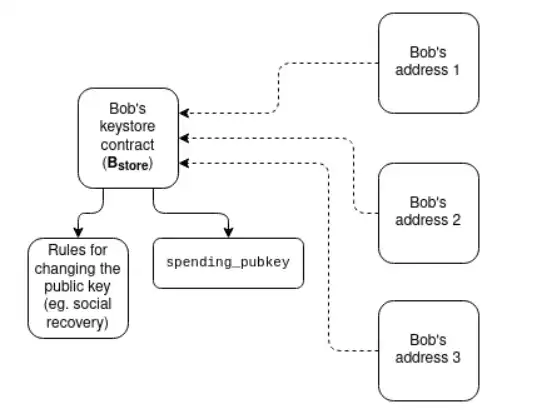

Keystore Wallet Operations

A keystore wallet is a wallet type with modifiable validation logic (for changing keys, signature algorithms, etc.), and these changes automatically propagate to all L2s. Validation logic resides on L1, while L2s read it via synchronous reads (e.g., L1SLOAD, REMOTESTATICCALL). Keystore wallets could place validation logic on L2, but that adds complexity.

Assume each user performs one key change or account upgrade annually, with 3.1 billion users. At 50,000 gas per operation, gas consumption per slot is: 50000 * 3100000000 / (31556926 / 12) ~= 59 million—about 3.3x the current target.

We can reduce costs significantly via optimization—e.g., initiating key changes on L2 but storing data on L1 (credit to Scroll team for this idea). This reduces gas cost to just one storage write and minor computation (assume 7,500 gas), allowing keystore updates to use about half of Ethereum’s current gas capacity.

We can also estimate keystore operation cost: 7500 * 15 * 10**-9 * 2500 = $0.28. From this perspective, a 1.1x L1 expansion would suffice to make keystore wallets affordable.

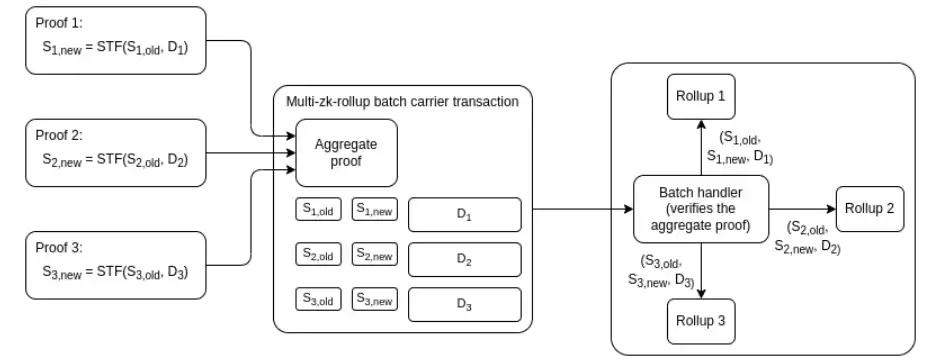

L2 Proof Submission

To make cross-L2 interoperability fast, general-purpose, and trustless, L2s need to frequently submit proofs to L1 so they can directly know each other’s state. For optimal low latency, L2s need to submit every block to L1.

With current technology (e.g., ZK-SNARKs), submission cost per L2 is about 500,000 gas, meaning Ethereum can support at most 36 L2s (in contrast, L2beat tracks ~150 L2s including validiums and optimiums). More importantly, this is nearly economically infeasible: assuming long-term average gas price of 15 gwei and ETH price of $2,500, annual submission cost is: 500000 * 15 * 10**-9 * (31556926 / 12) * 2500 = $49 million/year.

With aggregation protocols, costs can be further reduced, eventually bringing per-submission gas down to about 10,000 gas (aggregation is more complex than updating a single storage slot). This reduces annual cost per L2 to about $1 million.

Ideally, we want every block to be submitted to L1 as a matter of course. Achieving this requires massive L1 capacity expansion. $100,000/year is manageable for L2 teams, but $1 million/year is not negligible.

Conclusion

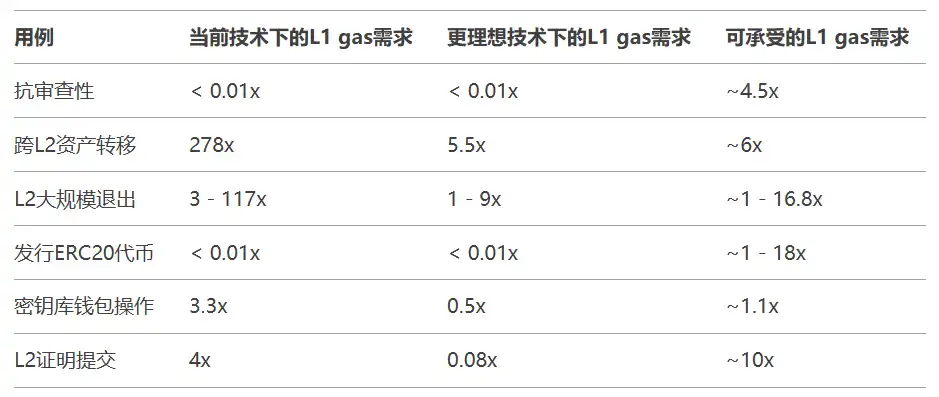

We can summarize the above use cases in the following table:

Note that the first and second columns are additive. For example, if keystore wallet operations consume half of current gas usage, sufficient space must remain for a mass L2 exit operation.

Also note again that cost-based estimates are extremely rough. Demand elasticity (how gas fees respond to gas limit changes, especially long-term) is very hard to estimate, and even at fixed usage levels, there remains great uncertainty about how fee markets will evolve.

Overall, this analysis shows that even in an L2-dominated world, a 10x expansion of L1 gas has significant value. This implies that short-term L1 scaling achievable within the next 1–2 years remains valuable regardless of long-term outlook.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News