Acemoglu, the newly awarded Nobel laureate: How to view the current development and risks of AI?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Acemoglu, the newly awarded Nobel laureate: How to view the current development and risks of AI?

Technology and society, the greatest asset is people.

Original author: Chen Qihan, reporter at The Paper

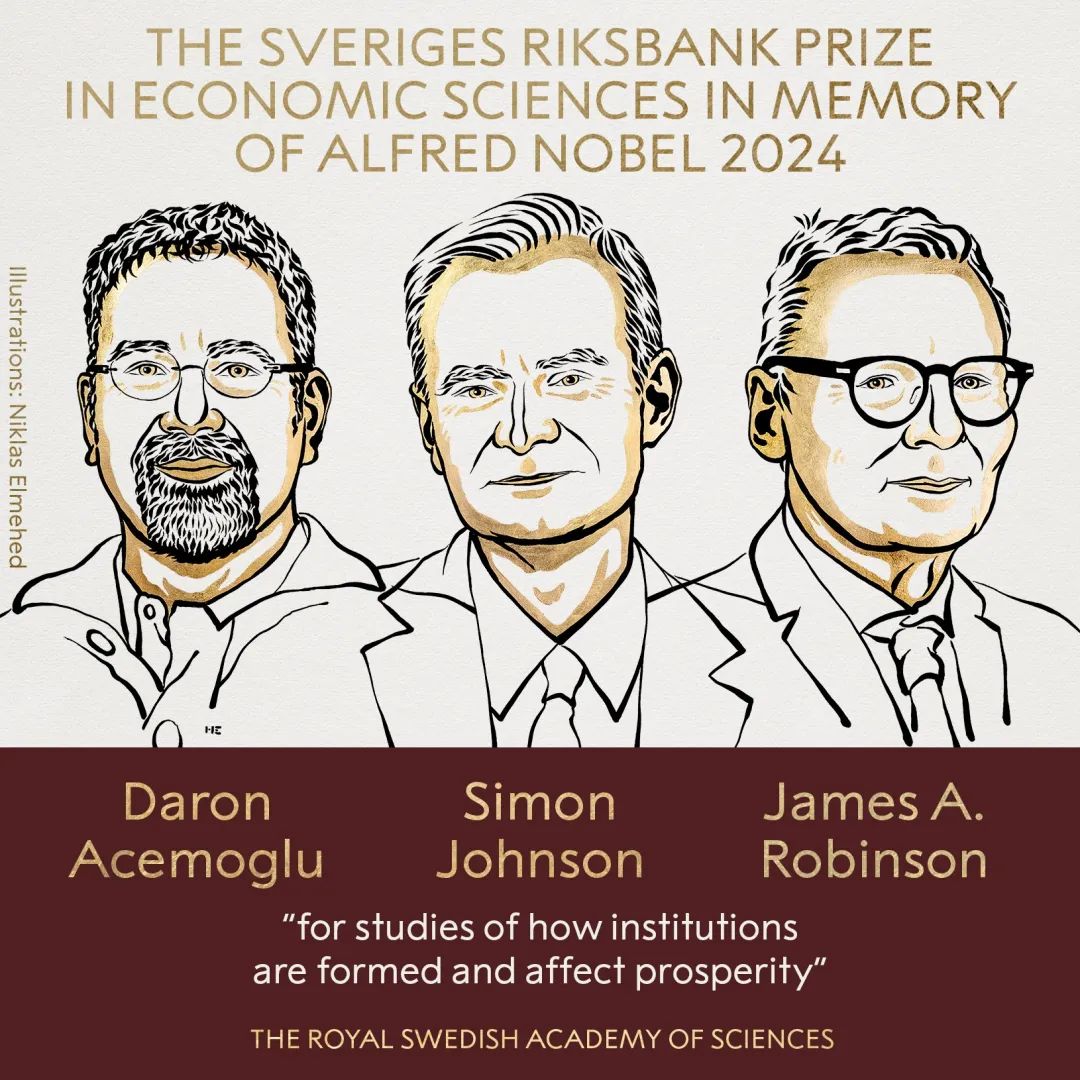

On October 14 local time, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced that the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics would be awarded to Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson for their "studies on how institutions are formed and how they affect prosperity."

In a press release, the selection committee stated that these three economists have demonstrated the importance of social institutions for national prosperity. "Societies with weak rule of law and institutions that exploit people cannot generate growth or positive change. Their research helps us understand why," it said.

Acemoglu was born in Istanbul, Turkey's capital, in 1967. He has been teaching at MIT since 1993 and received the Clark Medal in 2005. His research spans political economy, economic development, economic growth, technological change, inequality, labor economics, and network economics. He has co-authored numerous papers with the two other laureates and written bestsellers such as *Why Nations Fail* and *The Narrow Corridor* with Robinson.

In recent years, one focus of Acemoglu’s research has been the impact of automation technologies like industrial robots on labor markets. In 2023, he co-authored *Power and Progress* with Simon Johnson, a book addressing the dilemmas posed by AI—the most significant technology of our era.

"Much of my research focuses on the interaction between political economy and technological change—two powerful forces shaping our capabilities and opportunities for advancement, while also influencing our political and economic choices," Acemoglu told The Paper in an exclusive interview in June this year.

His research reveals that the current trajectory of AI is repeating and amplifying some of the worst technological mistakes made over the past few decades. For example, excessive emphasis on automation without sufficient investment in creating new tasks for workers. He believes business leaders must recognize that their greatest asset is their workforce—not cost-cutting, but rather enhancing worker productivity, skills, and influence should be the priority.

Acemoglu is deeply concerned that AI could become a mechanism transferring wealth and power from ordinary people to a small group of tech entrepreneurs. To counteract the political dominance of large tech companies, he argues that "antitrust alone is not enough; we need to redirect technology toward socially beneficial ends."

He proposes three guiding principles for AI development: first, prioritize machine usefulness; second, empower workers and citizens instead of manipulating them; third, establish a stronger regulatory framework to hold tech firms accountable.

*Below is an exclusive interview with Acemoglu conducted by The Paper on June 16, 2024, originally titled “Interview | MIT Professor: Worried AI Will Become a Tool Transferring Wealth and Power to a Few Tech Entrepreneurs”.

According to a report by Reference News citing CNN on June 15, Apple surpassed Microsoft on the 13th to become the U.S.'s most valuable publicly traded company. After announcing a series of updates—including generative AI features for iPhone—at its annual Worldwide Developers Conference last week, Apple's stock price surged.

Apple, Nvidia, and Microsoft have been fiercely competing for the title of the world’s most valuable company. After rebranding its artificial intelligence initiative as “Apple Intelligence,” Apple overtook Nvidia—whose valuation had skyrocketed due to AI chips—and then edged past Microsoft to reclaim the top spot. Apple’s current market value stands at $3.29 trillion, slightly above Microsoft’s $3.28 trillion. Generative AI has become the core driver behind the soaring valuations of these three tech giants.

In response to this AI boom, the National Bureau of Economic Research recently published a paper authored by MIT professor Daron Acemoglu, suggesting that productivity gains from future advances in artificial intelligence (AI) may be modest. The study estimates that AI will contribute no more than a 0.66% increase in total factor productivity (TFP) over the next decade.

Acemoglu notes in the paper that generative AI is a promising technology, but unless the industry undergoes fundamental reorientation—including major architectural changes to generative AI models (such as large language models, LLMs)—to focus on delivering reliable information that enhances the marginal productivity of workers across industries, rather than prioritizing general-purpose, human-like conversational tools, its potential will remain limited.

Acemoglu remains skeptical of overly optimistic forecasts about AI’s impact on productivity and economic growth. As a Turkish-born American economist renowned for his work in political economy, he has long studied the interplay between political economy and technological change.

Last year, he co-authored a new book, *Power and Progress*, with British-American economist Simon Johnson. The book discusses the AI revolution that could upend human society. They argue that AI development has already gone off track—many algorithms are designed primarily to replace humans. "But true technological progress means making machines useful to humans, not replacing them," they assert.

Mira Murati, OpenAI’s Chief Technology Officer, commented in May on the debate around developing Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), stating that their efforts focus not only on enhancing model functionality and practicality but also on ensuring safety and alignment with human values to prevent loss of control, thereby creating AGI that benefits humanity.

"The deeper I delve into AI’s capabilities and developmental direction, the more convinced I am that its current trajectory is repeating and intensifying some of the worst technological errors of the past few decades," Acemoglu said in a recent interview with The Paper (www.thepaper.cn). He added that most leading players in the AI field are driven by unrealistic and dangerous dreams—specifically, the dream of achieving AGI, which amounts to placing machines and algorithms above humans.

Some analysts regard Acemoglu as an AI pessimist. In response to The Paper, he said that as a social scientist, he naturally pays closer attention to negative societal impacts.

Acemoglu often collaborates with his wife, Professor Asu Ozdaglar, who heads the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT. Though working in different fields, the couple shares broadly aligned views on AI development. However, Acemoglu admits his outlook may be somewhat more pessimistic than hers.

As commercialization of AI accelerates and large AI models proliferate, tech giants like OpenAI, Microsoft, Google, and Nvidia have clearly seized early advantages in AI development. Acemoglu expressed deep concern that AI could become a vehicle for transferring wealth and power from ordinary people to a small group of tech entrepreneurs. The inequality we see today, he says, is a "canary in the coal mine"—a warning sign of worse things to come.

Technology and Society: People Are the Greatest Asset

Q1: Your research covers multiple areas including political economy, technological change, and inequality. Under what background and circumstances did you begin focusing on technology’s impact on inequality? What were your initial views on technological development, and how did they evolve into your current stance that “the current path of AI development is detrimental to both the economy and democracy”?

Acemoglu:

My research has largely focused on the interaction between political economy and technological change—two major forces shaping our capabilities and opportunities for growth, while also influencing our political and economic decisions.

AI has become the defining technology of our time, partly because it attracts immense attention and investment, and partly due to notable advancements—especially as GPU performance improves. But also because of its pervasive influence. These factors prompted me to study this domain.

The deeper I investigate AI’s capabilities and direction, the more convinced I become that its current trajectory is repeating and exacerbating some of the worst technological missteps of the past few decades—an overemphasis on automation, similar to how we previously prioritized automation and other digital technologies without adequately investing in creating new tasks; and social platforms profiting by exploiting user data and interests, repeating all those earlier mistakes.

I’m particularly concerned that most leading players in AI are driven by unrealistic and dangerous ambitions—namely, the pursuit of Artificial General Intelligence—which places machines and algorithms above humans, often serving as a way for these dominant players to elevate themselves above others.

Q2: Advanced computing technologies and the internet have enabled massive wealth transfers for billionaires and empowered tech giants to unprecedented levels. Nonetheless, we’ve accepted these innovations because they also brought positive outcomes. While technological change always brings trade-offs, historically societies have adapted. With a new wave of technological transformation underway, why do you find inequality especially troubling?

Acemoglu:

I agree with this view regarding social platforms and AI, but I differ when it comes to the internet. I believe the internet has been misused in certain ways. That said, I don’t deny it’s an immensely beneficial technology—it has played a crucial role in connecting people, providing information, and enabling new services and platforms.

With AI, I’m deeply worried it will become a mechanism transferring wealth and power from ordinary people to a small group of tech entrepreneurs. The problem is we lack essential control mechanisms to ensure ordinary people benefit from AI—such as strong regulation, worker participation, civil society engagement, and democratic oversight. The inequality we observe today is a “canary in the coal mine,” signaling that worse consequences lie ahead.

Q3: You’ve pointed out that inequality caused by automation is “a result of choices made by businesses and societies about how to use technology.” As tech giants grow increasingly powerful—even potentially uncontrollable—what are the key responses? If you were CEO of a major tech company, how would you use AI to manage it?

Acemoglu:

My advice to CEOs is to recognize that their greatest asset is their workforce. Rather than focusing solely on cutting costs, they should seek ways to enhance worker productivity, skills, and influence. This means using new technologies to create new tasks and expand human capabilities.

Of course, automation is beneficial, and we will inevitably adopt more of it in the future. But boosting productivity isn't the only thing we can do, and automation shouldn’t be the sole focus or priority for CEOs.

Q4: U.S. antitrust enforcers have publicly voiced concerns about AI. Reports suggest the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission have reached an agreement to pave the way for antitrust investigations into Microsoft, OpenAI, and Nvidia. Can such antitrust actions against big tech truly increase market competition and prevent AI development from being dominated by a few firms?

Acemoglu:

Absolutely—they can make a difference. Antitrust is important. A root cause of problems in the tech sector is the lack of antitrust enforcement in the U.S. The five major tech companies have established solid monopolies in their respective domains by acquiring potential competitors without any regulatory oversight. In some cases, they’ve purchased and shelved competing technologies to strengthen their monopolies. We desperately need antitrust action to dismantle the political power of big tech, which has grown extremely strong over the past three decades.

However, I also emphasize that antitrust alone is insufficient—we must redirect technology toward socially beneficial purposes. Simply splitting Meta into Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp won’t achieve greater competition or prevent AI dominance by a few companies. In AI, if we fear the technology being used for manipulation, surveillance, or other malicious ends, antitrust alone won’t solve it. It must be combined with a broader regulatory agenda.

Technology and Humans: How to Avoid Repeating Past Mistakes

Q5: You consistently emphasize “machine usefulness”—that is, making machines more beneficial to humans. How do you think we can achieve this goal? What consequences arise if we fail?

Acemoglu:

This ties back to my earlier advice to CEOs. We want machines that extend human capabilities. In the case of AI, there’s great potential to achieve exactly that. AI is an information technology, so we should ask: what kind of AI tools can provide useful, context-sensitive, real-time information to human decision-makers? We can use AI tools to make humans better problem-solvers, capable of handling more complex tasks. This applies not just to creative professionals, scholars, or journalists, but also to blue-collar workers, electricians, plumbers, healthcare providers, and every other occupation. Better access to information leads to smarter decisions and higher-level task execution—that’s what machine usefulness means.

Q6: You advocate fair tax treatment for labor. Is taxing equipment and software similarly to human employees, or reforming taxes to incentivize employment over automation, a practical solution?

Acemoglu:

Yes, Simon Johnson and I jointly proposed in *Power and Progress* that a fairer tax system could be part of the solution. In the U.S., the marginal tax rate faced by firms when hiring labor exceeds 30%. When they use computer equipment or machinery to perform the same tasks, the tax rate is less than 5%. This creates excessive incentives for automation while discouraging employment and investment in training and human capital. Equalizing the marginal tax rates on capital and labor is a reasonable policy idea.

Q7: You propose tax reforms to reward employment rather than automation. How would such reforms affect corporate application and investment in automation technologies?

Acemoglu:

We must be cautious not to discourage investment, especially since many countries need rapid growth and require fresh investments in areas like renewable energy and healthcare technology. But if we can encourage technology to develop in the right direction, it will ultimately benefit businesses too. My proposal is to eliminate excessive incentives for automation, aiming to do so in a way that doesn’t broadly deter business investment.

Q8: The rapid rise of social platforms has brought negative consequences such as information bubbles and the spread of misinformation. How can we avoid repeating the same mistakes as AI continues to evolve?

Acemoglu:

Three principles can help avoid repeating past errors: (1) Prioritize machine usefulness, as I’ve advocated; (2) Empower workers and citizens instead of trying to manipulate them; (3) Introduce a better regulatory framework to hold tech companies accountable.

Technology and Industry: Digital Advertising Tax to Boost Competition

Q9: Technology expert Jaron Lanier emphasizes user ownership of internet data. In terms of policy, how should individual data ownership and control be better protected?

Acemoglu:

I think this is an important direction. First, we’ll need increasing amounts of high-quality data, and the best way to produce such data is by rewarding those who create it—data markets can facilitate this. Second, data is currently being extracted by tech companies in an unfair and inefficient manner.

However, the key point is that data markets aren’t like fruit markets. My data is often highly substitutable for yours, so if tech companies negotiate individually to buy personal data, a “race to the bottom” will occur, resulting in very high administrative costs. Therefore, I believe a well-functioning data market requires some form of collective data ownership—such as data unions, data industry associations, or other collective organizations.

Q10: What do you think about introducing a digital advertising tax to curb profit-making from algorithm-driven misinformation? What impact might such a tax policy have on the digital advertising industry and information dissemination?

Acemoglu:

I support a digital advertising tax because the business model based on digital ads is highly manipulative. It aligns with strategies that provoke emotional outrage, digital addiction, extreme jealousy, and information silos. It also synergizes with business models exploiting personal data, leading to mental health issues, social polarization, declining civic engagement in democracies, and other negative outcomes.

Worse still, if we want to redirect AI development as I suggest, we need new business models and platforms. But today’s ad-based model makes that nearly impossible. You can’t launch a new social platform based on user subscriptions or replicate Wikipedia’s success because you’re up against companies offering free services with massive user bases. So, I see the digital advertising tax as a way to make the tech industry more competitive: if the “low road” of harvesting user data and profiting from digital ads is curbed, new business models and more diverse products will emerge.

Q11: Can you share some positive changes you foresee from future technological developments, and how we should prepare for and promote them?

Acemoglu:

If we use AI correctly, it can enhance the professional skills of workers across all industries and improve the process of scientific discovery. I also believe there are ways to use AI democratically.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News