The 1987 "Black Monday" Revisited: What Happened After Herd Trading Reversed and Liquidity Shocks Struck?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The 1987 "Black Monday" Revisited: What Happened After Herd Trading Reversed and Liquidity Shocks Struck?

The danger lies in the fact that a sharp decline could become self-reinforcing and evolve into a credit crunch.

By Ying Zhao, Wall Street Insights

The "1987-style Black Monday" unfolded again yesterday, with global financial markets plunging in a crash-like manner, filled everywhere with terms like circuit breakers, bear markets, and historical records.

Japan's Nikkei 225 and the Topix Index both plunged over 12%, triggering circuit breakers multiple times during trading; Taiwan's stock market recorded its largest drop since 1967, South Korea saw its biggest decline since 2008, the Dow dropped more than 1,000 points, and the S&P 500 posted its worst two-day loss in two years, while platforms such as Futu and Fidelity issued warnings of trading disruptions.

The last time global markets endured such a painful shock was on October 19, 1987—the infamous stock market crash.

Back then, Asia-Pacific markets tumbled sharply—Nikkei fell 14.9%, Hang Seng Index plummeted over 40%, and New Zealand’s index even briefly crashed by 60%. The U.S. market also descended into chaos: the Dow plunged 22.6% in a single day, the S&P 500 collapsed nearly 30%, wiping out approximately $1.71 trillion from global equity markets.

Beyond similar levels of devastation, the triggers behind both crashes were also alike: a massive reversal in arbitrage and program trading. With history as a guide, what comes next? Will the Federal Reserve step in once again to rescue the market?

"1987-Style Black Monday"

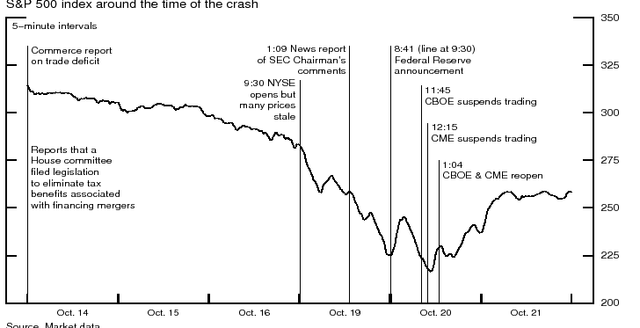

Looking back at the U.S. stock market in 1987, the trade deficit released by the U.S. government on October 14 exceeded expectations, causing the dollar to depreciate and pushing markets lower.

On Friday, October 16, the U.S. House of Representatives proposed legislation eliminating certain tax benefits related to leveraged buyouts, intensifying the sell-off and setting the stage for further turmoil in the week ahead.

When markets opened on Monday, October 19, panic set in as sellers vastly outnumbered buyers. Due to the extreme imbalance, many floor market makers did not provide quotes in the first hour of trading.

The U.S. SEC later noted that by 10:00 a.m., 95 out of 500 S&P 500 component stocks had yet to open. The Wall Street Journal reported that 11 out of the 30 Dow Jones components failed to open for trading.

Meanwhile, as large arbitrage gaps emerged between stock index futures and underlying equities, institutional traders engaged in arbitrage strategies. As the stock market continued to fall, significant hedging activity led to massive shorting in index futures, which in turn accelerated the downward spiral of stock prices.

At close, the Dow Jones Industrial Average collapsed by 22.76%, marking the largest one-day percentage drop since 1929.

Before markets opened on Tuesday, October 20, the Federal Reserve issued a brief statement announcing emergency measures—"an immediate 50 basis point rate cut plus quantitative easing" to stabilize the market:

"The Federal Reserve today reaffirmed its responsibility as the nation's central bank and confirmed its willingness to serve as a source of liquidity to support the economy and financial system."

Markets stabilized on the day of the Fed’s announcement. U.S. stocks continued falling early in the session, the Chicago Board Options Exchange and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange suspended trading at noon, resumed in the afternoon, and then staged a partial rebound.

On October 21, markets began recovering some lost ground.

Unwinding of Arbitrage and Program Trading Ignites the Crash

Similar to 1987, the 2024 "Black Monday" was triggered by a perfect storm.

Back then, the U.S. stock market had been in a bull run since 1982, and many believed it was due for a correction. Today, investors are similarly wary of the tech-led rally driven by the AI boom.

Secondly, the reversal of crowded trades played a key role. In the 1987 crash, "program trading" was widely blamed—one of the culprits—as portfolio insurance programs automatically sold stocks, creating a domino effect.

The recent market plunge was partly driven by narrowing U.S.-Japan interest rate differentials, which triggered a reversal in carry trades. The Bank of Japan unexpectedly raised rates last week, while the Fed signaled rate cuts after its meeting, making a September cut almost fully priced in. This eroded the appeal of the popular "sell yen, buy dollar" carry trade, prompting investors to unwind dollar-denominated assets and repatriate yen.

Additionally, the Friday before the 1987 crash coincided with the so-called "triple witching day"—the simultaneous expiration of stock options, stock index futures, and index options—which caused severe instability in the final hours of trading and carried over into Monday’s opening.

Finally, analysts attribute the sharp decline to "mass hysteria." During every major market downturn, investor herd behavior tends to amplify the fall.

Will the Fed Step In Again to Rescue the Market?

With history as a guide, what actions might the Federal Reserve take?

In response to the 1987 market crash, the U.S. implemented an "emergency rate cut," introduced circuit breakers, and injected liquidity to stabilize markets.

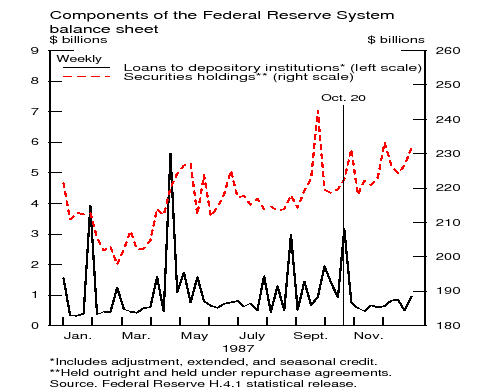

To slow the financial market slide and prevent spillovers into the real economy, the Fed swiftly moved to inject liquidity into the financial system, pumping billions of dollars through quantitative easing measures.

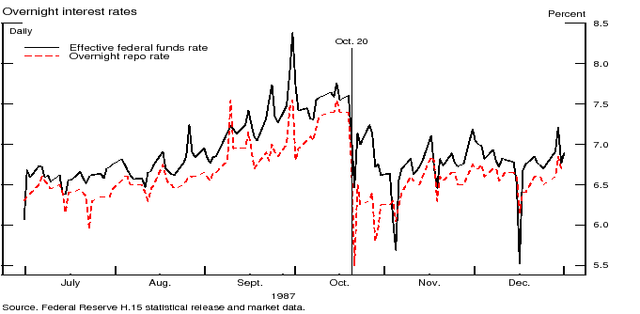

At the same time, then-Fed Chair Alan Greenspan announced an "emergency 50 basis point rate cut," lowering the federal funds rate from above 7.5% on Monday to around 7% on Tuesday.

Moreover, regulators introduced circuit breakers for the first time to prevent market collapses caused by program trading. If abnormal price movements occurred, trading would be immediately halted.

How Will the Sell-Off End?

Analysts believe the worst-case scenario could be a repeat of 2008, but this seems unlikely. Although some large U.S. banks collapsed last year due to failed bets on government bonds, overall bank leverage is far lower than before. Additionally, since private credit has taken on much of the risk previously held by banks, the banking system is less vulnerable to liquidity crises. Significant losses are possible, and private funds may face distress—but this would unfold over time and not trigger an identical systemic crisis.

The best-case scenario is that excessive market volatility gradually subsides, just as it did in 1987, without causing broader damage—though the calming process is expected to be slower than in 1987. AI-driven speculation could lead to further price declines; even after a 30% drop from June highs, Nvidia’s stock is still up 100% this year. However, markets are now closer to normal levels—the Nasdaq 100 is up only 6% year-to-date, and the S&P 500 is up less than 9%.

Ed Yardeni, known as the "father of bond vigilantes," believes:

"The danger in a market crash lies in its potential to become self-reinforcing and evolve into a credit crunch. It's conceivable that the unwinding of carry trades could escalate into a financial crisis, potentially leading to a recession."

However, he emphasized that his personal forecast does not foresee such an outcome.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News