From Value Silos to Interoperability: A History of Bitcoin's Layered Development

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

From Value Silos to Interoperability: A History of Bitcoin's Layered Development

Bitcoin is the first successfully implemented non-sovereign hard currency.

Author: SAURABH DESHPANDE

Translation: TechFlow

Throughout history, money has fulfilled three key functions in society: it serves as a store of value (wealth), a medium of exchange, and a unit of account. While the form of money constantly evolves, its core functions remain largely unchanged. Broadly speaking, there have always been two schools of thought—one supporting credit or soft money, and the other advocating hard money. Credit money, like today’s fiat systems, is always some form of liability.

The dollars or rupees you hold represent government debt. If the government defaults, your money will no longer buy basic goods and services.

In contrast, hard money is not a government liability. For example, precious metals like gold do not lose value even if a government defaults. Instead, due to their perceived stability, their value increases.

Bitcoin is the first successfully implemented non-sovereign hard money. In 2009, Satoshi Nakamoto launched Bitcoin just after the world experienced a global financial crisis caused by poor lending practices and unilateral interest rate decisions. The strong dollar has lost over 95% of its purchasing power over its lifetime. In his article Paradigm Shifts, macroeconomic master Ray Dalio wrote about how central banks lower interest rates in response to various crises and the impact this has on their respective economies.

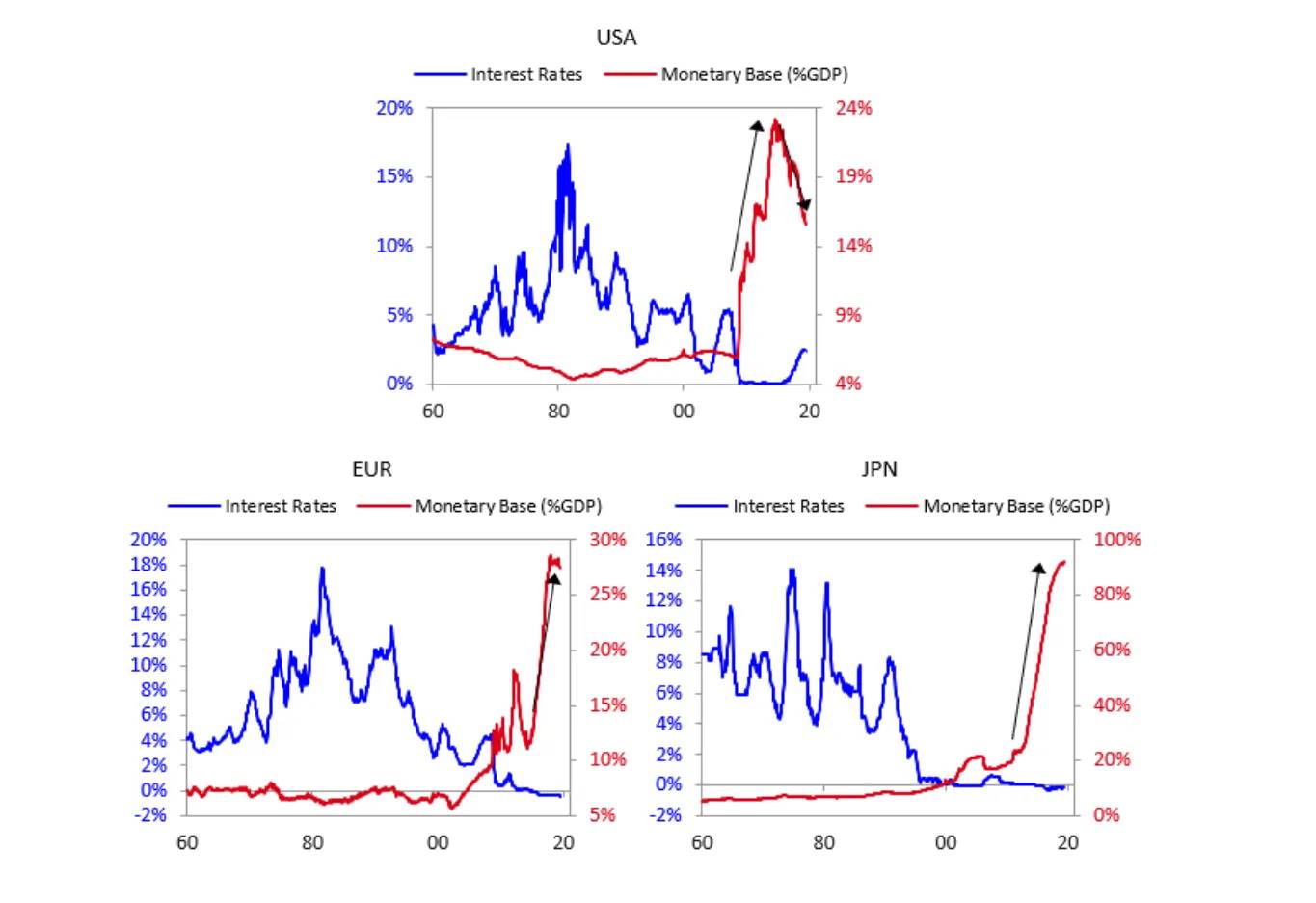

Source – Paradigm Shifts

The chart shows how interest rates in developed nations have declined since the 1980s. At the same time, the monetary base as a percentage of GDP has grown. As a result, total output hasn't kept pace with money supply growth. When the money supply grows rapidly, it can lead to higher inflation, increased cost of living, heavier debt burdens, and greater income inequality—regardless of household income growth. Our current high-inflation environment is a consequence of policies adopted by central banks.

Under such conditions, the role of precious metals like gold becomes more prominent. Government interference in gold supply is minimal. Due to limited government influence, gold supply is more predictable than fiat currency. This high predictability allows gold to maintain its value over decades and serve as a reliable store of wealth.

Bitcoin was born as peer-to-peer electronic cash. Over the years, like many innovations, it has deviated from (or at least expanded) its original goal of electronic cash and evolved into digital gold.

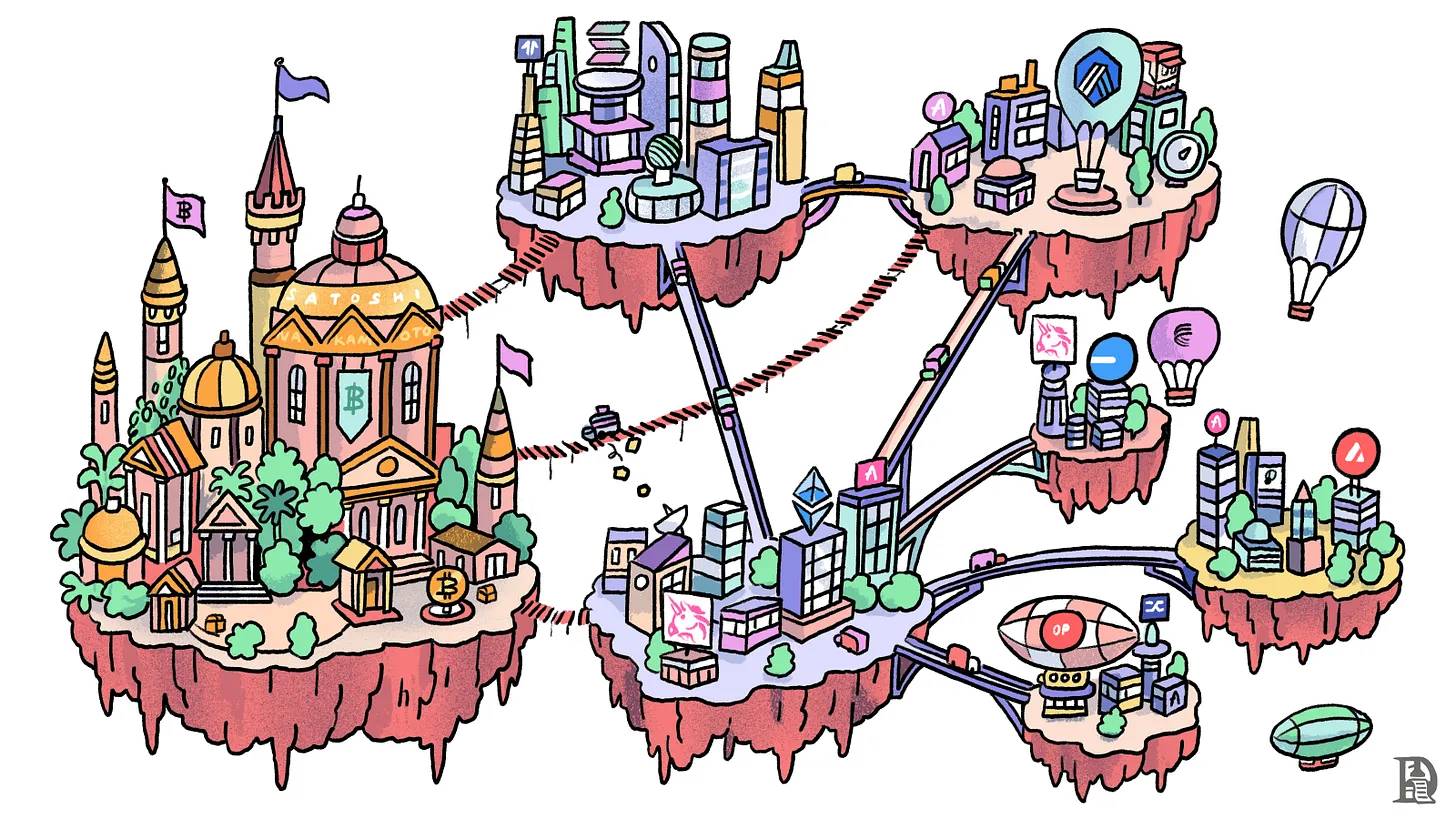

In 2018, I came across an interesting analogy comparing blockchains to cities. Because blockchains are isolated from the outside world, they resemble closed islands. Each island has its own priorities and technical and social characteristics. The Bitcoin island has always prioritized security and decentralization above all else, including speed and programmability.

Decentralization is a broad and nuanced term. Balaji Srinivasan suggests measuring decentralization by breaking a blockchain down into subsystems such as mining, clients, developers, exchanges, nodes, and ownership. He proposes that overall decentralization can be derived by measuring Gini1 and Nakamoto2 coefficients of these subsystems.

According to many Bitcoin supporters such as Jonathan Bier, we can assess decentralization by how difficult it is for users to independently verify transactions. The difficulty of transaction verification is why Bitcoin blocks are small (up to 4 MB). To make a blockchain generally programmable—not just in theory but in practice—developers must orchestrate certain things.

First, the language or system used should be Turing-complete. "Turing-complete" means the system can perform any computation expressible via an algorithm, given sufficient time and memory.

Second, gas metering needs to be optimized. Gas metering refers to how the system is designed to measure resource costs (e.g., maximum gas per block and gas consumed by different operations). Ethereum's Solidity is a Turing-complete language, but it is often constrained by gas limits. Bitcoin’s scripting language is intentionally limited to ensure higher security. Moreover, as Matt pointed out, it is a low-level stack-based language full of unpatched bugs since Satoshi's era, missing critical operators that limit its usefulness.

Blockchains like Ethereum and Solana have evolved into interconnected states, forming synergies from which they benefit. However, while the Bitcoin island firmly adheres to its security goals, it has not incorporated changes into its infrastructure that would allow easier movement to other blockchains. The Bitcoin island only permits residents to hold, transfer, or trade BTC for inscriptions and runes, resulting in a poor user experience.

Due to limited use cases, BTC is primarily stored in vaults. Meanwhile, assets like ETH offer rich opportunities to earn yield and passive income through staking, restaking, lending, and more. As other chains develop new infrastructure, they undergo rapid modernization, while Bitcoin remains ancient yet powerful.

Don’t get me wrong—the conservative approach of Bitcoin ensures its security and decentralization. More features usually bring complexity, increasing the attack surface.

The Bitcoin island remains strong but isolated. Other blockchains are connected by stronger bridges.

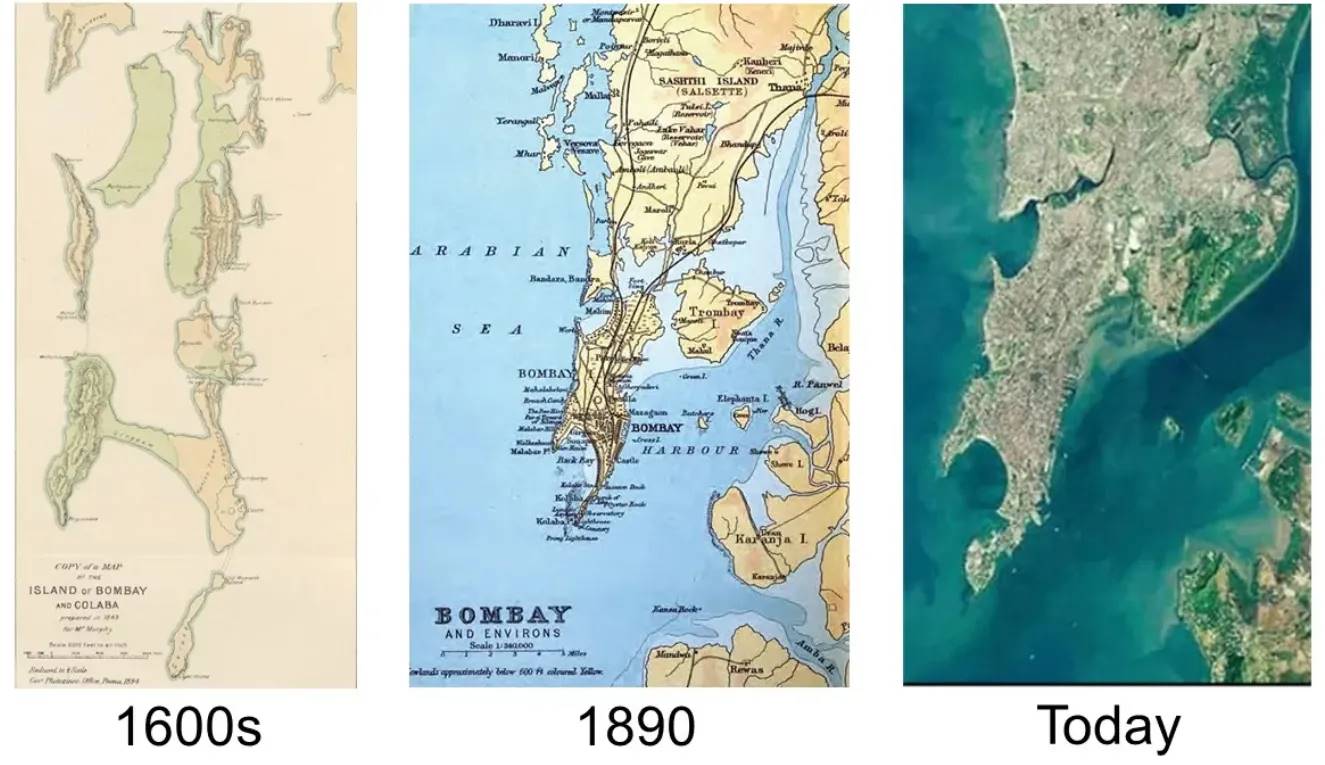

These separated islands remind me of the history of my hometown, Mumbai. Once known as Bombay, it originally consisted of seven distinct islands. Their fusion began in the 1680s and continued over centuries. Today, as I walk through this bustling metropolis, almost no trace remains of its fragmented past. The city feels seamlessly unified, its former divisions nearly forgotten.

This transformation of Mumbai raises an interesting question: Will we witness a similar evolution in the Bitcoin ecosystem? Some teams are already working toward it.

Evolution of the seven islands of Mumbai. Source – Reddit

This article explores how some teams are providing Bitcoin holders with different ways to use their wealth beyond simply holding it. I’ll lay the foundation by explaining why we need better infrastructure, then dive into the different approaches teams are taking to expand BTC use cases. Finally, I touch on the ultimate vision, which involves not just technical consensus but also social consensus.

This shift is happening because teams are building auxiliary islands around the Bitcoin island and seeking solutions to modernize it. Permanent reform of the Bitcoin island can only occur after a social revolution among its residents who collectively agree to change its rules—only then can bridges to other islands be used as confidently as internal infrastructure.

Why Better Infrastructure Is Needed?

Established blockchains like Ethereum, Solana, and the upcoming Monad are developer-centric by design. They are built as platforms for developers to build applications. These chains provide comprehensive ecosystems supported by various learning resources, tools, frameworks, and functionalities. Satoshi did not consider these when developing Bitcoin. Bitcoin lacks a well-thought-out API and has almost no clear documentation for learning Bitcoin development.

There are three key reasons why network infrastructure must continuously improve—better user experience (UX), greater financialization, and scalable payments.

Better UX Will Increase Activity and Generate More Fees

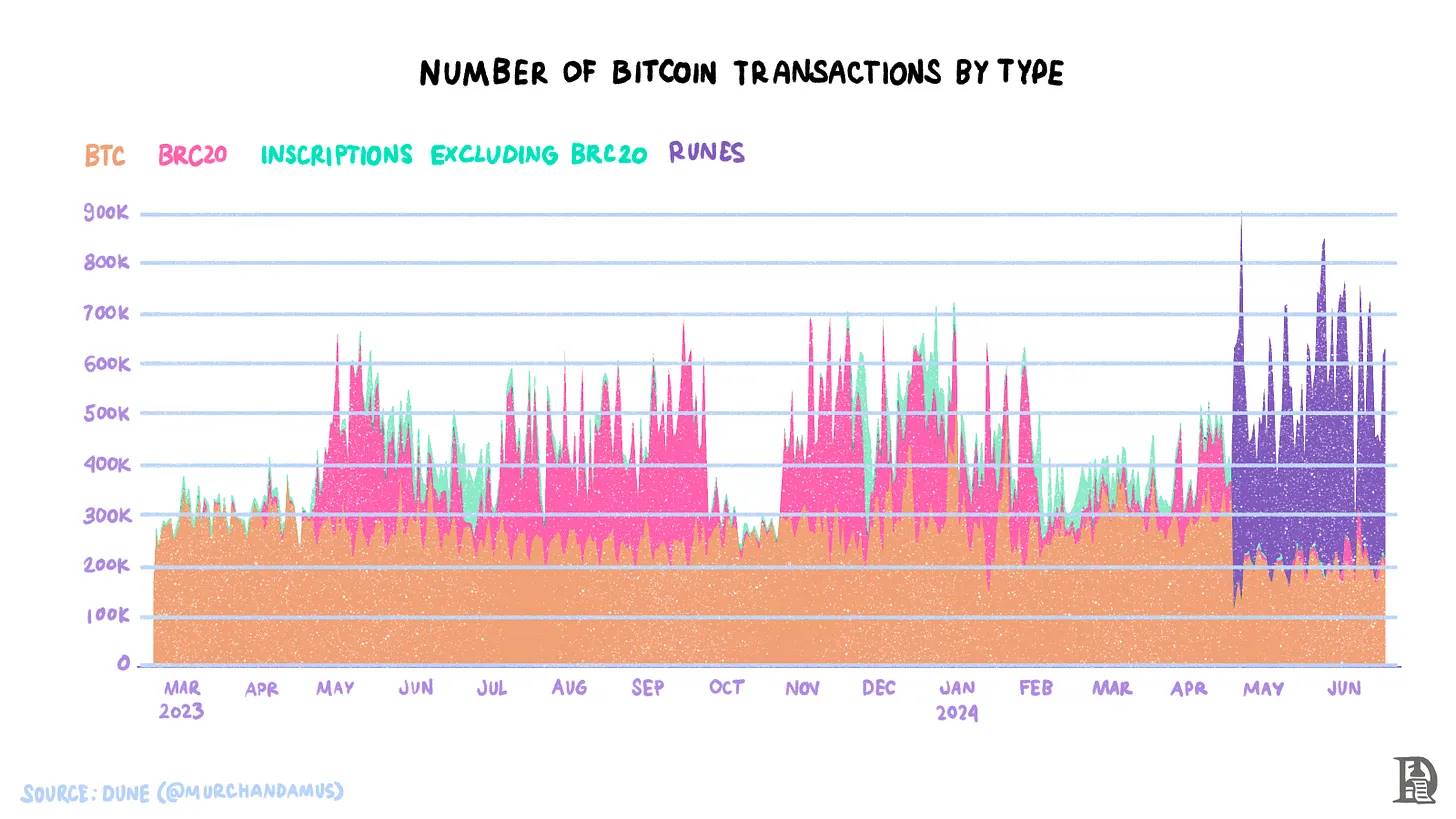

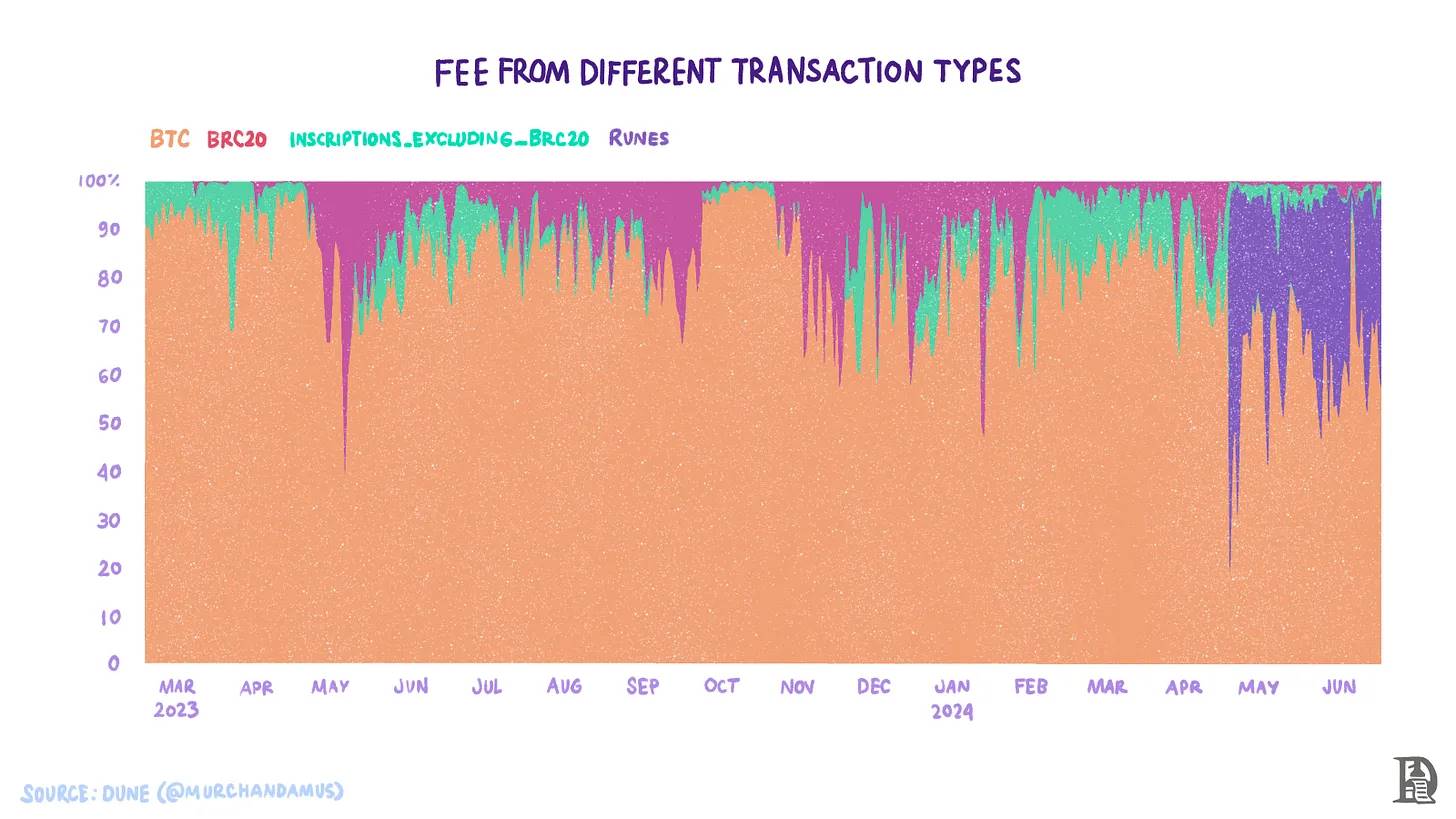

The Ordinals protocol, which leverages Bitcoin UTXOs and views individual Satoshis (the smallest unit of BTC) differently, brought innovations like inscriptions (NFTs on Bitcoin). The excitement around Ordinals and inscriptions led to the emergence of fungible standards like BRC-20 and Runes. Inscriptions and Runes have boosted activity on Bitcoin. Total daily transactions have increased by about 70% compared to BTC-only transfers.

These new Bitcoin transaction methods helped increase fees by approximately 40%. However, these innovations sparked heated debates within the Bitcoin community. One faction believes Bitcoin should focus on strengthening its core function as a decentralized payment system. They argue that expanding beyond this scope could harm Bitcoin’s security, simplicity, and effectiveness as sound money.

On the other hand, advocates of a more flexible approach argue for extending Bitcoin’s functionality to include non-payment use cases. They believe such evolution is necessary for Bitcoin to remain competitive and relevant in the rapidly advancing blockchain ecosystem.

Is this enough? Not quite. According to Token Terminal data, Bitcoin miners earned about $109 million in fees over the past 30 days. During the same period, applications like Uniswap and Lido Finance earned $90 million and $104 million respectively. After the latest halving in April 2024, miners’ block subsidies were reduced by 50%. Following the recent halving, the block reward (subsidy) decreased from 6.5 BTC to 3.125 BTC per block. This results in a monthly subsidy reduction of 13,500 BTC (3.125 × 144 × 30), worth approximately $891 million at $66,000 per BTC. Thus, monthly fees currently cover only about 12% of the lost subsidy.

Recent developments like Runes are encouraging, but we need more. What are the challenges? Bitcoin’s user experience lags far behind chains like Solana or Ethereum L2s such as Arbitrum. A swap on Solana takes seconds and costs mere cents. But if you want to trade Runes on Bitcoin, you pay several dollars in fees and wait for a block confirmation.

Moreover, when buying Runes, you must purchase the full listed amount—you cannot modify the quantity. Another downside is that Runes cannot be directly swapped with each other, unlike on Ethereum where you can exchange USDC for MKR. Traders must first sell one Rune for BTC, then buy the desired Rune. This extra step adds unnecessary friction to the user experience.

The Rune trading experience is far from ideal. There’s no way to use BTC as collateral or borrow against it. You must move BTC off the Bitcoin L1 to another chain to use it in financial applications.

Increasing BTC Financialization

First, Bitcoin’s market cap is close to $1.3 trillion, with each BTC priced at $66,000. Like gold, Bitcoin is outside money—meaning governments cannot manipulate its supply. While the exact size of the gold lending market isn’t available, some reports estimate it at $100 billion. Therefore, one of the most important reasons to build applications on Bitcoin is to enable borrowing stablecoins using native BTC as collateral. A robust lending market would allow Bitcoin holders to earn yield on their BTC.

Take staking, for example. Native assets like ETH and SOL have intrinsic uses in staking to secure network safety; about 27% of circulating ETH is staked in staking protocols, yielding about 4% annually. Another 4% of ETH is staked in restaking protocols, and 67% of circulating SOL is staked. Additionally, both ETH and SOL are widely used as collateral assets within their respective DeFi ecosystems.

Wrapped BTC (WBTC) is the most widely used version of BTC across different DeFi ecosystems, with a market cap of about $10 billion—less than 1% of total circulating BTC. This highlights the vast potential for BTC financialization.

Assuming BTC usage in staking or DeFi reaches levels similar to Ethereum—around 30%—this figure could reach $390 billion. By comparison, the total value locked (TVL) across all other chains in DeFi is currently $101 billion. BTC could become the most productive liquid asset, but currently this potential is constrained by intentional technical limitations.

Scaling BTC Payments

Bitcoin’s base layer wasn’t designed for high throughput. If Bitcoin is to become the settlement layer of the internet, we need faster transaction speeds. As Mohamed Fauda noted, the number of transactions published this way is limited. With a maximum block size of 4MB, Bitcoin can support 6.66 kbps (4 MB / 10 minutes) of data.

The Bitcoin network currently cannot handle high traffic. Users face poor experiences during anticipated events like Quantum Cats mints and Rune launches. Poor UX affects not only those trying to mint inscriptions but also those sending and receiving BTC.

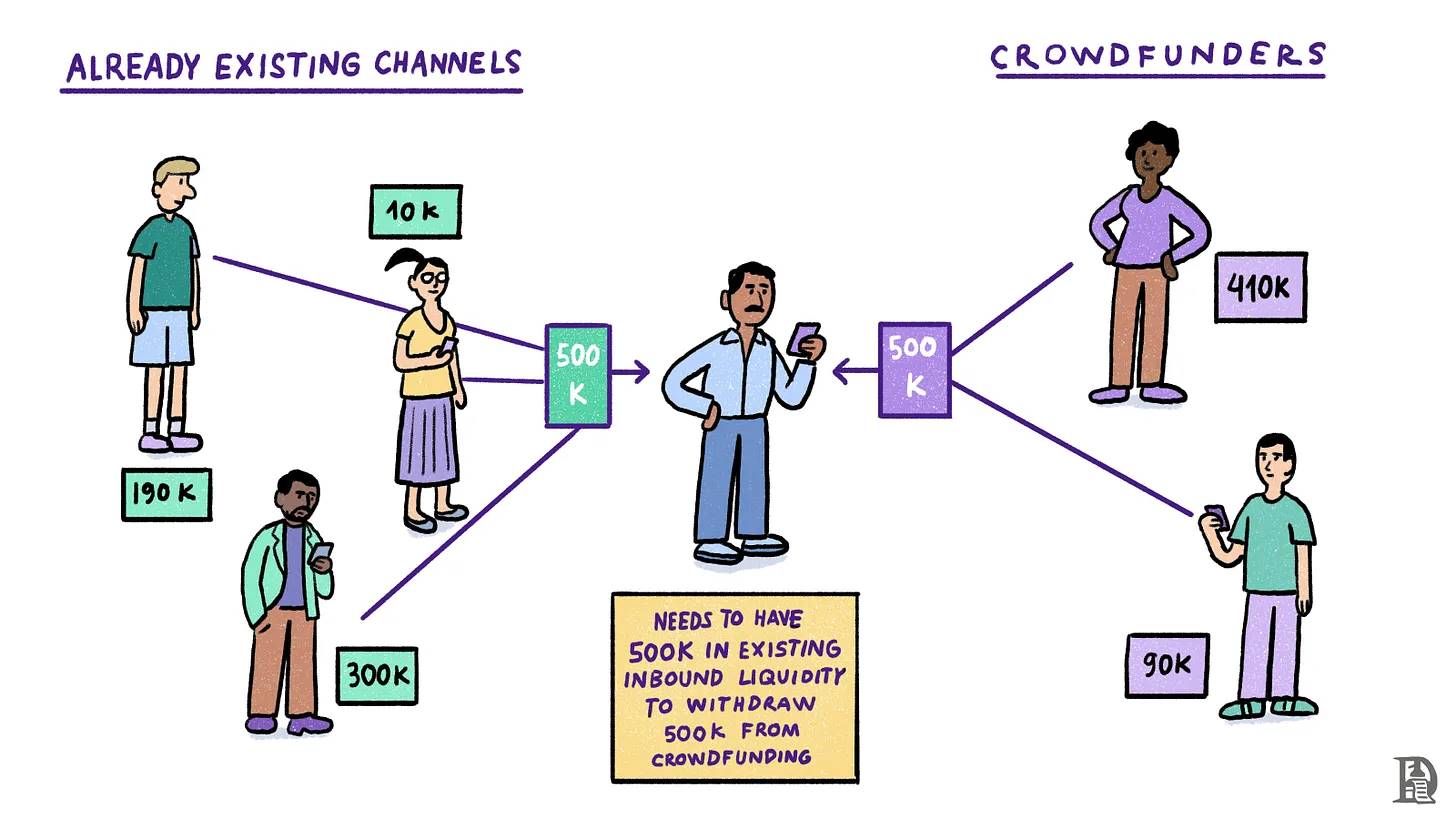

The Lightning Network (LN), the leading BTC scaling solution, has seen poor adoption. Its network capacity or liquidity is around 5,000 BTC—the amount of BTC locked in all Lightning channels. This impacts the network’s liquidity and the volume of BTC that can be moved through it.

Why does this matter? Let’s understand with an example. Joel is raising $1 million to pay coffee farmers in India and decides to accept donations via LN. He can’t just launch an LN wallet and start receiving donations. He needs $1 million in inbound liquidity. Inbound liquidity is the amount of BTC your counterparty locks in the channel. Sid, one of Joel’s counterparties, locks $10,000. Joel needs more counterparts like Sid whose combined deposits total $1 million to receive $1 million in donations. This presents a major challenge for network scalability, as inbound liquidity will always be constrained by capital opportunity costs.

Challenges in Bitcoin Development

Bitcoin is both a cultural and technological phenomenon. Social consensus is the final line of defense. For example, the hard-coded 21 million supply cap could technically be modified by forking the code to add a 1% tail emission. But for this change to take effect, all miners would need to mine on this fork—an unlikely scenario. This is because the hard-coded cap has long been one of BTC’s primary value drivers. Breaking this cap could be perceived as devaluing BTC. Miners are unlikely to mine on a fork that risks losing value.

Without social consensus, the technical effort required to modify the codebase becomes futile. The last contentious fork on Bitcoin occurred during the 2017 block size war. The network split into two parts: Bitcoin implemented SegWit (explained later), and Bitcoin Cash increased the block size. At the time, most hash power remained with BTC.

For something regarded as money or a store of value, frequent changes are undesirable. The main reason fiat currencies lose purchasing power over time is that central banks frequently use their power to increase supply. The unpredictability of such unilateral actions by central banks makes some currencies perpetually weaker. Bitcoin culture resists change. Even non-controversial upgrades like Taproot took years from conception to implementation.

Implementing the above changes isn’t just about modifying Bitcoin. Bitcoin’s base layer needs to remain as simple as possible. Simplicity is crucial to reduce attack vectors and enhance stability. The idea is to execute complex tasks—like lending and issuing stablecoins backed by BTC—outside the base layer, similar to Ethereum’s L2s.

Bitcoin L2?

What defines an L2? It should:

-

Provide sufficient data to Layer 1 to verify and resolve disputes (if any).

-

Have no additional security assumptions beyond the base layer.

-

Allow users to unilaterally withdraw their assets back to the base layer (Layer 1).

Due to Bitcoin’s current opcodes limiting its ability to verify any proofs, these conditions cannot be met. Therefore, any chain claiming to be a Bitcoin L2 cannot be considered a true L2.

Another critical aspect of an L2 is that its security assumptions must align with Bitcoin’s. Every blockchain has fundamental security assumptions, such as:

-

Most mining nodes are honest

-

Nodes can independently verify blocks and reject invalid ones

-

Forks resolve on the longest chain, etc.

An L2 should not extend the security assumptions of the base layer it’s built upon. For example, if an L2 has a centralized sequencer monopolizing block production, users need to be able to challenge block production at low cost. As long as a user’s funds haven’t been spent, the base layer should be able to instruct the L2 to release the user’s funds. Currently, even some consensus-layer Ethereum L2s lack these mechanisms.

If we strictly adhere to the above L2 characteristics, even some established Ethereum L2s like Arbitrum aren’t truly L2s. Due to Bitcoin’s opcode limitations preventing proof verification, no chain claiming to be a Bitcoin L2 qualifies as a real L2. The Lightning Network might be the only solution meeting the L2 definition. As a general term, this article refers to these solutions as Bitcoin scaling layers.

Current State of Bitcoin Scaling Layers

Overall, there are two main pathways to using BTC: 1) Using cross-chain bridges due to Bitcoin’s limited native applications, and 2) Creating an environment or chain where applications using BTC can reside for investors.

To enable more use cases and scaling, new layers may introduce additional security assumptions atop Bitcoin. Users wanting to use their BTC will likely favor solutions requiring minimal security compromises. Ethereum’s scaling roadmap serves as a useful reference for understanding how its scaling design space evolved.

After years of development, Ethereum recognized rollups as its key scaling method. Currently, we still don’t know which approach is best for scaling and making BTC more programmable.

Whether storing data or choosing bridge designs, projects make trade-offs between decentralization, security, speed, and user experience. Answers to the following questions constitute the design space for projects or companies building Bitcoin scaling layers:

-

How is bridging achieved from Bitcoin to the new chain?

-

How is data stored (data availability)?

-

How is settlement performed using Bitcoin Layer 1?

-

Does the vision require any changes to Bitcoin’s base layer?

-

Which execution environment is chosen?

-

Does the scaled Bitcoin layer promote BTC usage for purposes like gas and staking?

Teams are making different trade-offs to provide better functionality and scalability for BTC holders.

Bridging Mechanisms

BTC on Bitcoin cannot be directly transferred to other chains, so infrastructure is needed to enable such cross-chain transfers. A typical bridging mechanism involves locking a user’s BTC on the Bitcoin network and minting an equivalent amount of synthetic tokens on the target chain to represent these BTC.

What is a typical locking mechanism? When a user wants to transfer BTC from the Bitcoin network to another chain, they send BTC to a specific address on Bitcoin. This address is controlled by the bridge operator. When the bridge operator detects the arrival of BTC, they mint an equivalent amount of synthetic tokens on the target chain and send them to the user’s specified address.

The risk with this mechanism is that if the bridge operator loses the BTC on the Bitcoin network, the synthetic tokens minted on the target chain become worthless. We witnessed this risk after the collapse of FTX. SolBTC, a wrapped version of BTC operated by FTX/Alameda, became worthless because FTX stopped honoring redemptions after filing for bankruptcy.

Therefore, all user activities on the target chain entirely depend on how the bridge operator manages and safeguards the user’s BTC on the Bitcoin network. Based on how BTC is managed, different bridging mechanisms fall into three categories.

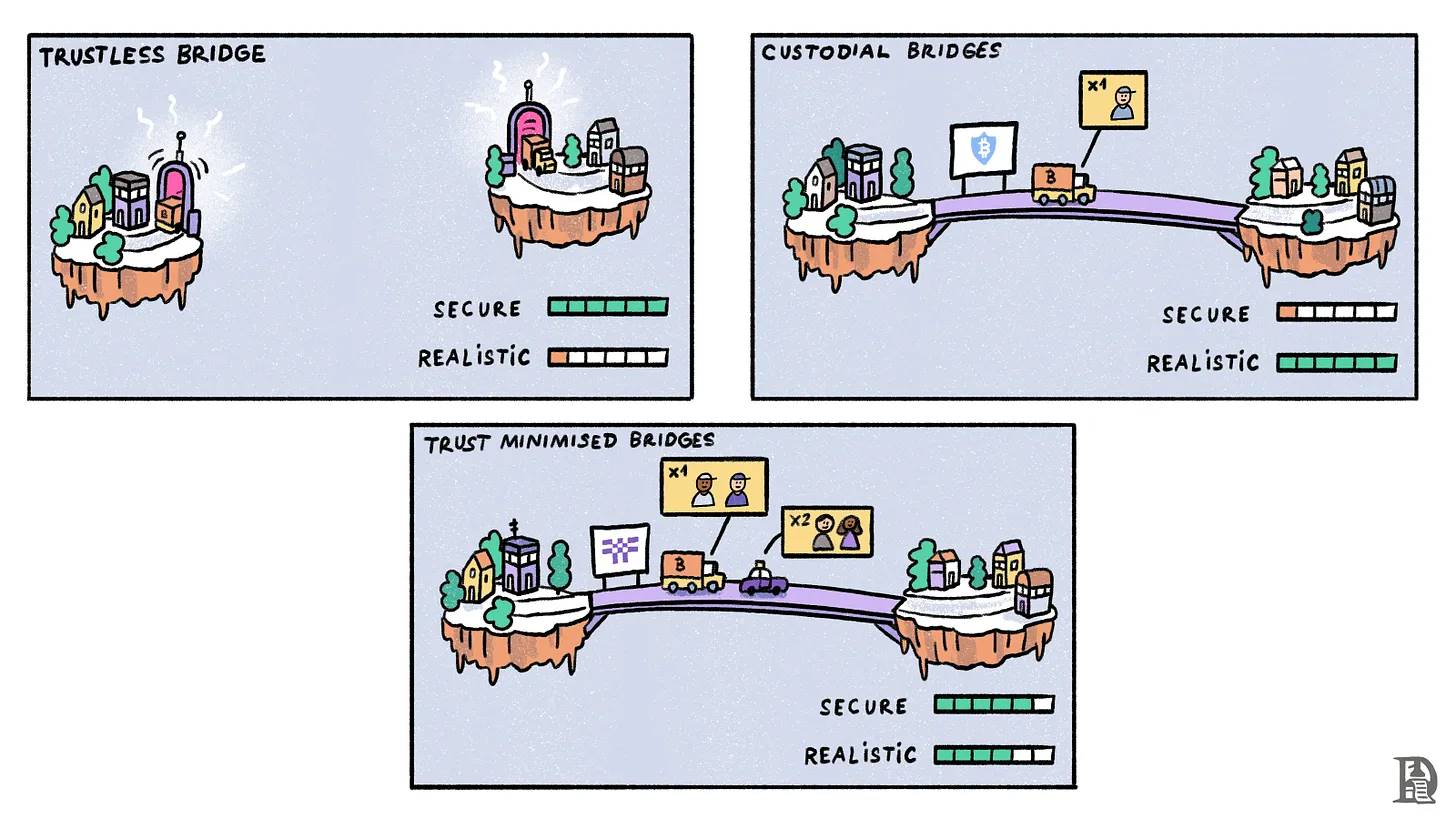

Trustless Bridges

This bridging mechanism is only possible when Layer 1 (L1) can verify proofs submitted by Layer 2 (L2). For Bitcoin, this mechanism is currently unfeasible because Bitcoin cannot comprehend anything happening outside itself.

Trust-Minimized Bridges Relying on Economic Security

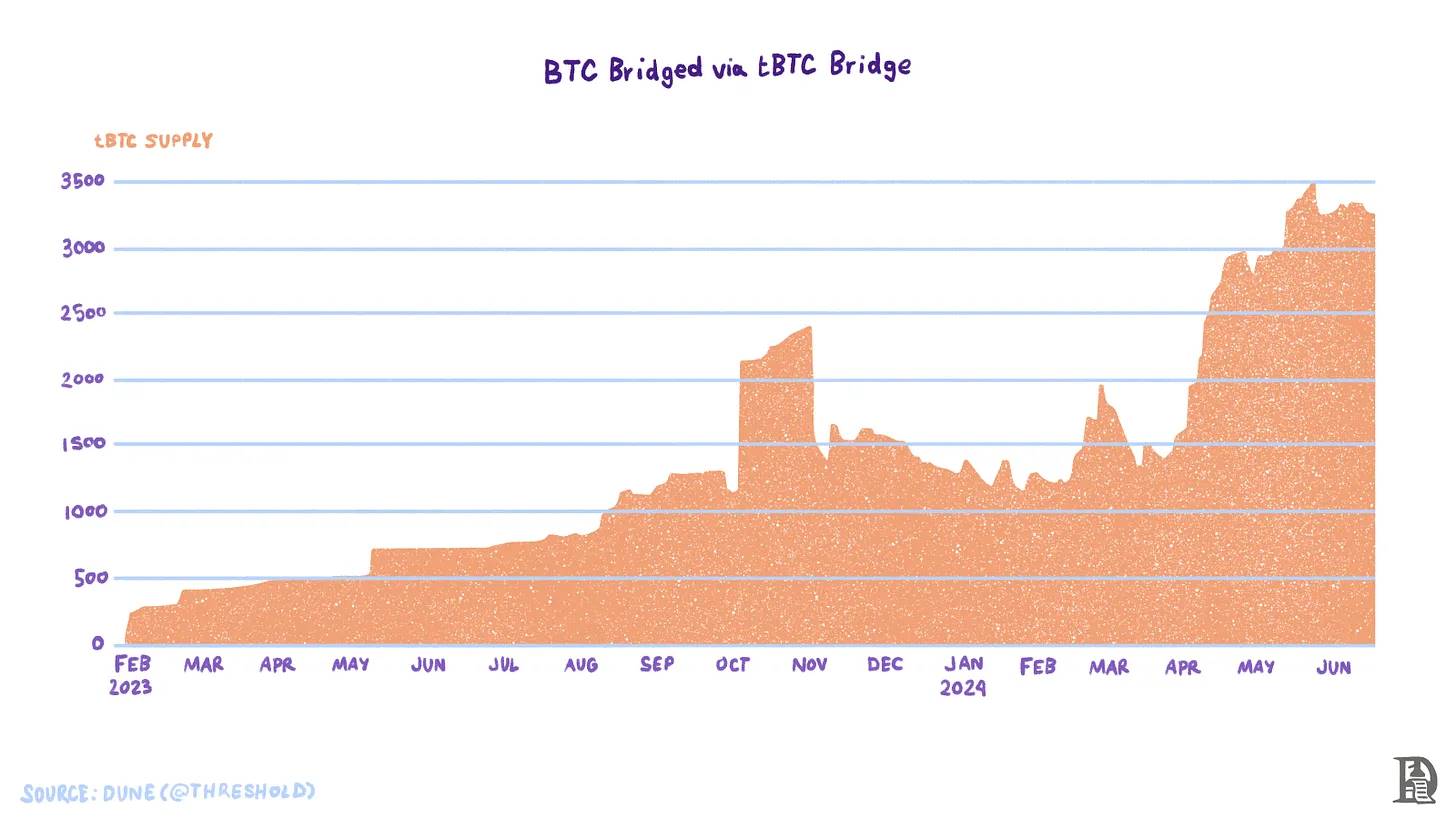

Another option for BTC bridging is having multiple public parties handle BTC locking and unlocking. These public parties safeguard users’ BTC on the Bitcoin network and mint/burn synthetic BTC tokens on other chains. Threshold Network’s tBTC is an example of this mechanism, relying on honest majority.

This means that before any operation on users’ BTC can be executed, a majority of operators running Threshold Network nodes must agree. Unlike relying on a centralized intermediary, tBTC randomly selects a group of node operators from the Threshold Network to protect deposited BTC.

Who can become a Threshold Network node operator? The network has a governance token T. While T is used for governance, at least 40,000 T is required to become a node operator. As of June 25, 2024, there are 139 active nodes on the network.

The tBTC Beta Stakers program aims to gradually decentralize the node network. Beta stakers can delegate their stake to five professional node operators—Boar, DELIGHT, InfStones, P2P, and Staked. Beta stakers are expected to run nodes for at least 12 months and actively participate. For example, they need to respond promptly to network upgrades, ideally upgrading their nodes within 24 hours of notification.

Whenever a user requests to mint tBTC, a new deposit address is generated on the Bitcoin network. This address is dedicated to the user and controlled by nodes on the Threshold Network. Users can request tBTC minting on networks like Ethereum, Arbitrum, Optimism, Mezo, and Solana.

Users must provide two addresses—a recovery address on Bitcoin (where BTC will be refunded if something goes wrong during minting) and a target chain address (where the user wants to receive tBTC). Once the request is made, the user must deposit BTC into the generated address and wait for guardians to confirm the deposit. After confirmation, the minter sends tBTC to the user’s address on the target chain.

Currently, Threshold Network has locked approximately 3,500 BTC, worth over $200 million.

Given the capabilities of Bitcoin opcodes, trust-minimized bridges are arguably the best bridging implementation currently available. Specific implementations of trust-minimized bridges may vary based on multisig design. Examples include tBTC by Threshold Network, Stack’s upcoming sBTC implementation, and Botanix’s spiderchain.

Custodial Bridges

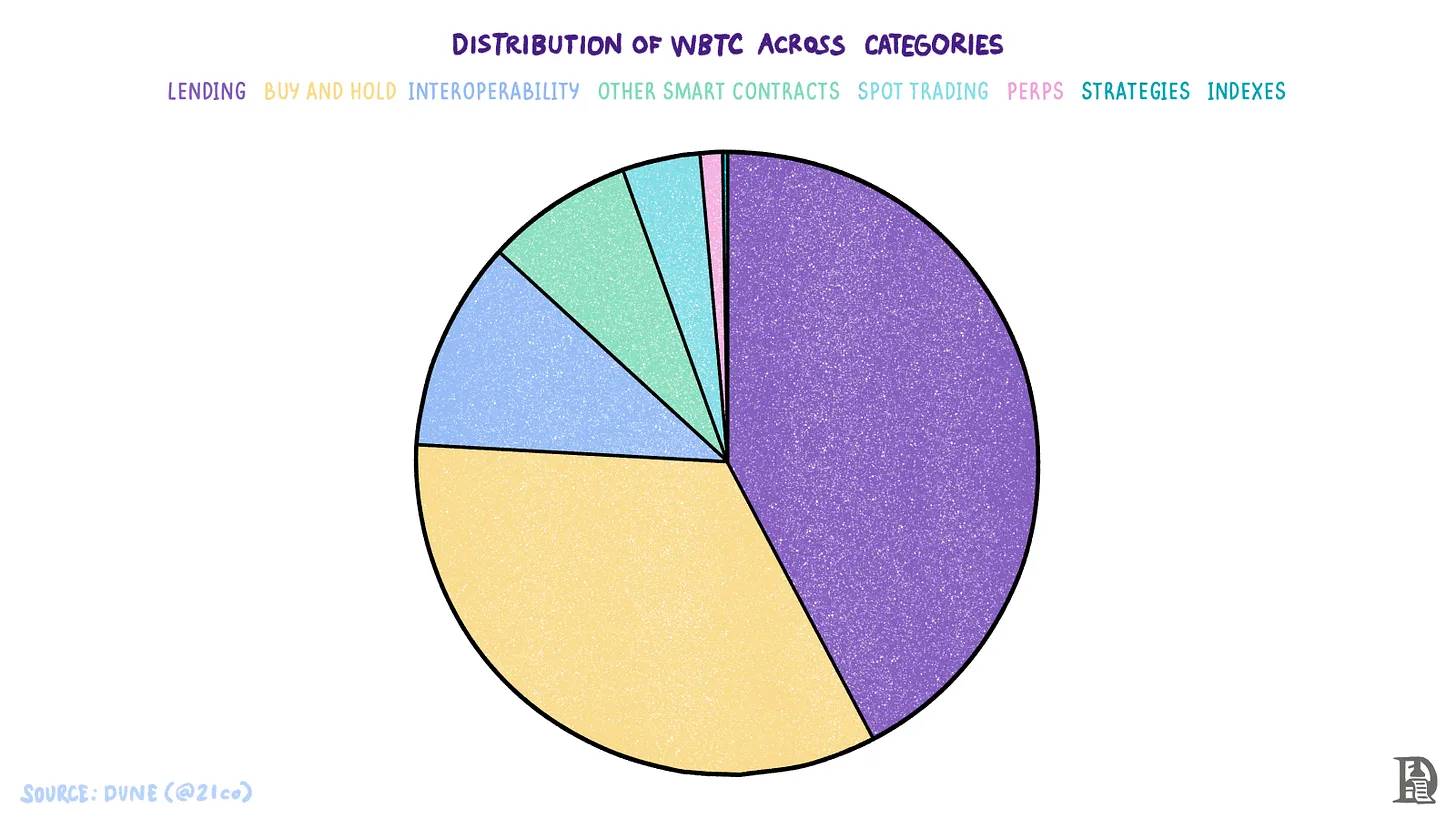

In this design, a centralized provider locks users’ BTC in addresses managed by custodians. BitGo’s WBTC is the most widely used method for bridging BTC to other chains, with over 150,000 BTC bridged via WBTC. The current distribution of WBTC is as follows.

BitVM

Beyond the three existing bridge types, Robin Linus released the BitVM whitepaper at the end of 2023. BitVM proposes a new method to achieve Turing-complete smart contracts on Bitcoin. A system is called Turing-complete if it can perform any computation given sufficient time. As mentioned earlier, Bitcoin is intentionally designed to be Turing-incomplete, but BitVM proposes a way to overcome this without changing existing opcodes, suggesting a so-called trustless bridging mechanism.

The core idea of BitVM is to optimistically verify zero-knowledge (ZK) proofs on Bitcoin. Transactions are assumed correct unless challenged. This system typically assumes at least one honest verifier. If execution is incorrect, at least one honest verifier should raise a dispute.

Thus, as long as ZK proofs aren’t challenged, everything proceeds normally. If any dispute arises, the challenger and prover enter an on-chain challenge-response or bisection game. The exact definition of bisection games is beyond the scope of this article, but a link is provided for interested readers. The outcome of bisection games is increased on-chain transaction load.

Another significant flaw in early versions of BitVM is liquidity management. When users withdraw from the bridge, the system completes partial withdrawals, and bridge operators must pre-provide liquidity. Operators are later reimbursed from the bridge. As the amount locked in the bridge increases, operators must maintain more liquidity to fulfill withdrawals. This puts pressure on operators, making the design highly inefficient in terms of capital usage.

Suppose operators need to keep 10% of the bridge’s total value locked (TVL) as liquidity on average. If the bridge TVL is $10 billion, operators must maintain $1 billion in liquidity. As the bridge attracts more liquidity, operators need to hold larger BTC inventories. Tyler White and Rijndael wrote an excellent article detailing the issues with BitVM.

Execution Layer

To enhance BTC utility, designing a chain that provides optimal user experience (UX) is crucial. Developers must consider multiple factors when designing this chain.

-

Execution Environment – Should it adopt an EVM-compatible chain? EVM compatibility offers many advantages, such as:

-

Years of accumulated tools like wallets and bridges connecting other EVM chains, which developers can use directly.

-

Users are very familiar with this UX.

-

Ethereum’s Layer 2s have benefited from EVM compatibility. EVM-compatible L2s like Arbitrum and Optimism quickly attracted users and applications already on Ethereum. Non-EVM compatible L2s like Starknet face greater adoption challenges.

-

However, EVM also has drawbacks. Since EVM requires serial transaction execution, parallel processing isn’t possible. Newer execution environments like Solana Virtual Machine (SVM) and the upcoming Monad support parallel processing.

-

-

Data Availability – Similar to Ethereum, rollup solutions are emerging in the Bitcoin space. Depending on where and how data is stored, rollups take different forms. Some store state differences (the difference between two chain states after executing a batch of transactions) and validity proofs on L1. Some store compressed transaction data on L1, while others store only validity proofs on L1 and keep transaction data on a separate layer.

-

Some chains like Stacks use Bitcoin as a checkpoint mechanism. Stacks has much shorter block times than Bitcoin. Stacks publishes data between its blocks onto each Bitcoin block.

-

Execution layers can publish transaction data on Bitcoin via inscriptions. Recall Bitcoin’s 6.66 kbps bandwidth. Assuming compressed transactions are 10 bytes (typically around 20 bytes), a Bitcoin block could theoretically contain about 600 compressed transactions. However, this maximum is nearly impossible to achieve, as 4 MB blocks are rare, and dedicating the entire 4 MB space to inscriptions is even rarer.

-

Block size depends on the mix of SegWit and non-SegWit transactions. SegWit (Segregated Witness) separates transaction data from witness data. The idea is that not all data stored in a block is equally important. Instead of limiting block size to the traditional 1 MB, SegWit introduced a new 4 million weight unit limit. Thus, if a block contains only non-SegWit transactions, the limit is 1 MB. But if it contains only SegWit transactions, it can reach 4 MB.

-

Multiple teams are building layers on Bitcoin to leverage BTC’s massive liquidity. This article examines six different teams making varied trade-offs with interesting designs. We briefly describe how they work, their development stage, and progress to date.

Babylon

Babylon focuses on expanding BTC’s use as a staking asset. It proposes a novel approach distinct from other Bitcoin layers (so-called L2s), called remote staking BTC. Unlike locking BTC on the Bitcoin network to mint synthetic versions, it introduces the following mechanism:

-

Users lock their BTC in a self-custodied vault by creating a UTXO that can only be spent once. This UTXO can only be spent after a predetermined staking period ends or if the user burns the staked UTXO using their special EOTS (Extractable One-Time Signature).

-

After confirming the staking transaction, users can use their EOTS to validate blocks on PoS chains within the Cosmos ecosystem to earn rewards.

-

If users behave honestly, they can unlock their BTC at the end of the staking period or submit an unstaking transaction to the Bitcoin network.

-

If dishonest behavior is detected, the user’s EOTS is publicly revealed. Babylon’s overseers ensure at least one honest operator exists. This suite of programs acts as a relay for data between Bitcoin and Babylon. Submitter programs use OP_RETURN to submit Babylon checkpoints to the Bitcoin network. Reporter programs scan Babylon checkpoints and report them back to Babylon. If anomalies are detected, anyone (called a slasher) can use the public EOTS key and submit a Bitcoin transaction to claim the malicious user’s stake.

-

A common question is why the user can’t retrieve the stake themselves using the key. The answer may be that when miners see the transaction, if someone else submits the same transaction, miners will pick the one with higher fees. For example, if the stake is 5 BTC, the slasher could share 4.99 BTC with the miner and profit. In this case, the miner keeps most of the profit instead of the slasher. However, the malicious user loses most of the stake regardless—whether to the slasher or the miner.

While Babylon offers an interesting way to expand BTC usage, its mechanism is quite complex. For instance, although some PoS chains have been live for years, slashing mechanisms haven’t been successfully implemented on many PoS chains. Additionally, while Babylon can leverage remote staking to make BTC usable for securing other PoS chains, it requires a bridge to enable other BTC use cases like lending.

Build on Bitcoin (BOB)

Better known as BOB, Build on Bitcoin is an Optimism-based rollup settling on Ethereum as of June 2024. It claims to be an Ethereum L2 aligned with Bitcoin. BOB will launch in four phases:

-

Phase 1 – OP Stack Rollup. At this stage, it is purely an Ethereum rollup. Fraud proofs are not yet live on mainnet. Fraud proofs are mechanisms allowing anyone to challenge the validity of transactions included in a rollup batch.

-

Phase 2 – Ethereum rollup with Bitcoin security. At this stage, BOB will leverage Bitcoin merge mining. Merge mining allows miners to simultaneously protect (or mine) multiple chains alongside Bitcoin.

-

Phase 3 – Optimistic Bitcoin rollup via BitVM. BitVM is currently not live. When it launches improved over its current version, BOB will begin settling on Bitcoin using BitVM.

-

Phase 4 – ZK rollup on Bitcoin. After Bitcoin adopts opcodes enabling ZK proof verification, BOB will settle on Bitcoin using ZK proofs.

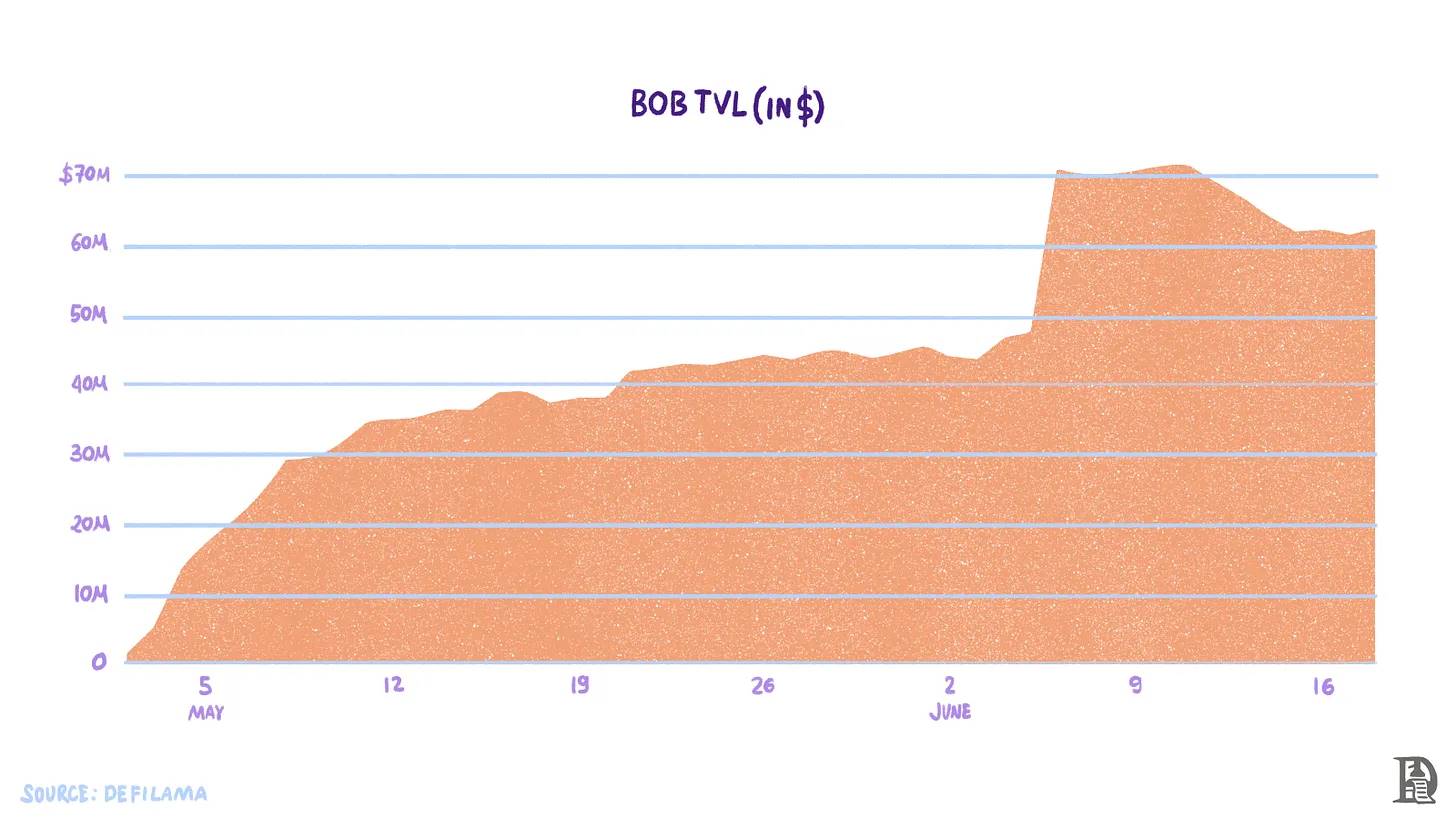

As of June 17, 2024, BOB’s TVL is about $60 million, with Sovryn DEX contributing about $20 million.

Botanix

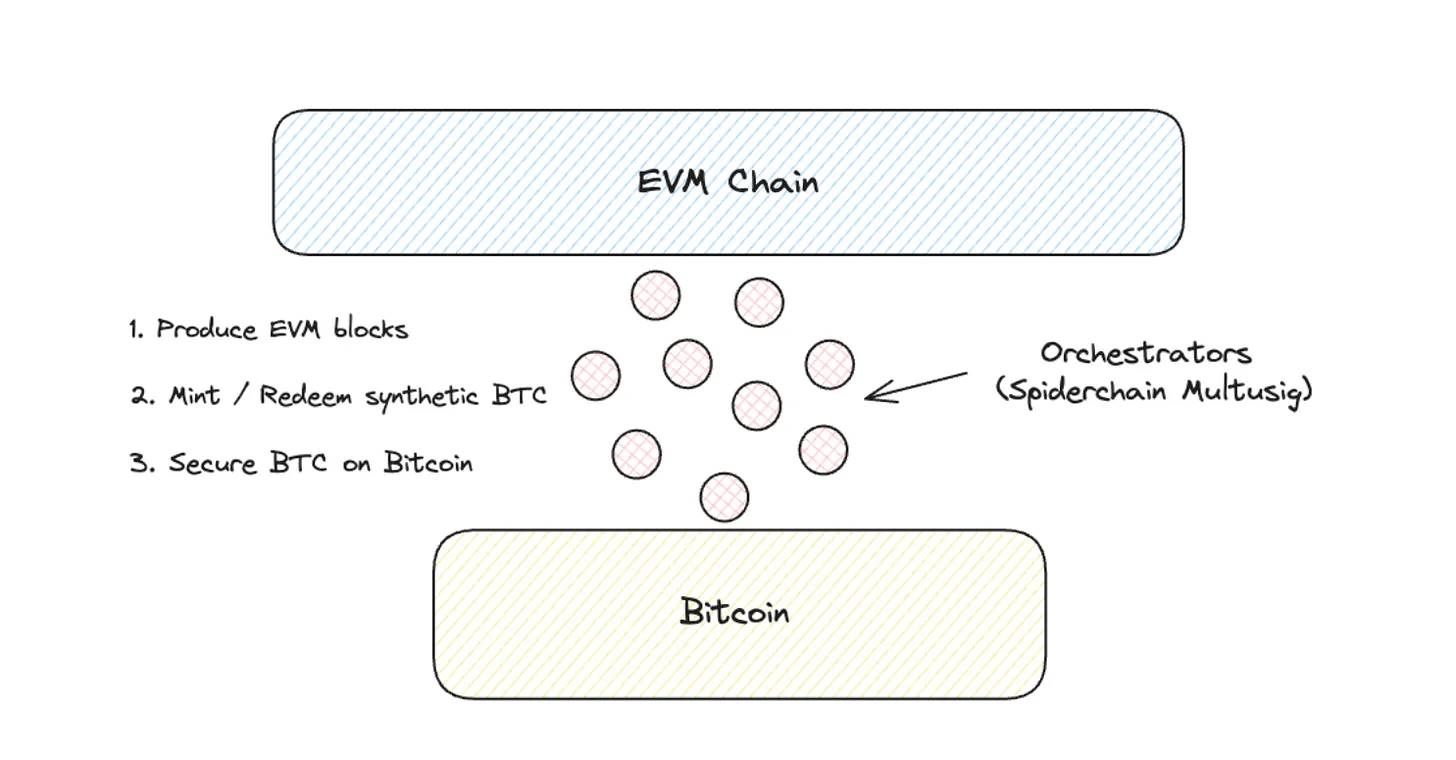

The Botanix team brings a significant innovation: Spiderchain. What is Spiderchain? It is a coordinating node for a rolling multisig mechanism on Botanix. Let’s explain in detail. As previously mentioned, an L2 needs a bridge and a chain to execute transactions. The coordinator is responsible for safeguarding user funds on Bitcoin and minting/burning synthetic BTC on the EVM layer. Coordinators run both Bitcoin and Spiderchain EVM (Botanix) nodes.

Suppose there are N coordinators on the network. Each Bitcoin block randomly selects M (< N) coordinators to safeguard incoming BTC. Each epoch, new keys are generated with a new set of coordinators. During bridging, newer BTC is selected first to ensure older and more established coordinators control older coins.

Botanix’s chain is EVM-compatible and secured by a PoS consensus mechanism. In addition to protecting BTC on Bitcoin through participation in the rolling multisig network and facilitating synthetic BTC minting and redemption, coordinators also participate in block production on the EVM chain. They post the root hash of Botanix EVM transactions (a compact version) as inscriptions on Bitcoin.

Note that merely publishing data on Bitcoin doesn’t mean settlement. The distinction is that data published externally by chains like Botanix via inscriptions is stored in places not verified by Bitcoin nodes (miners). The Bitcoin protocol is completely unaware of this data. Therefore, it’s impossible to determine whether transaction data published in inscriptions is correct.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News