Paradigm new article: MEV taxes and priority ordering

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Paradigm new article: MEV taxes and priority ordering

An MEV tax mechanism that allows any application to capture its MEV while preserving composability.

Authors: Dan Robinson, Dave White

Translation: Joyce, BlockBeats

Introduction

In this article, we introduce MEV taxes, a mechanism by which any application can capture its own MEV. This mechanism is now usable on OP Stack L2s such as OP Mainnet, Base, and Blast, because block proposers on these chains follow a set of rules we call competitive priority ordering.

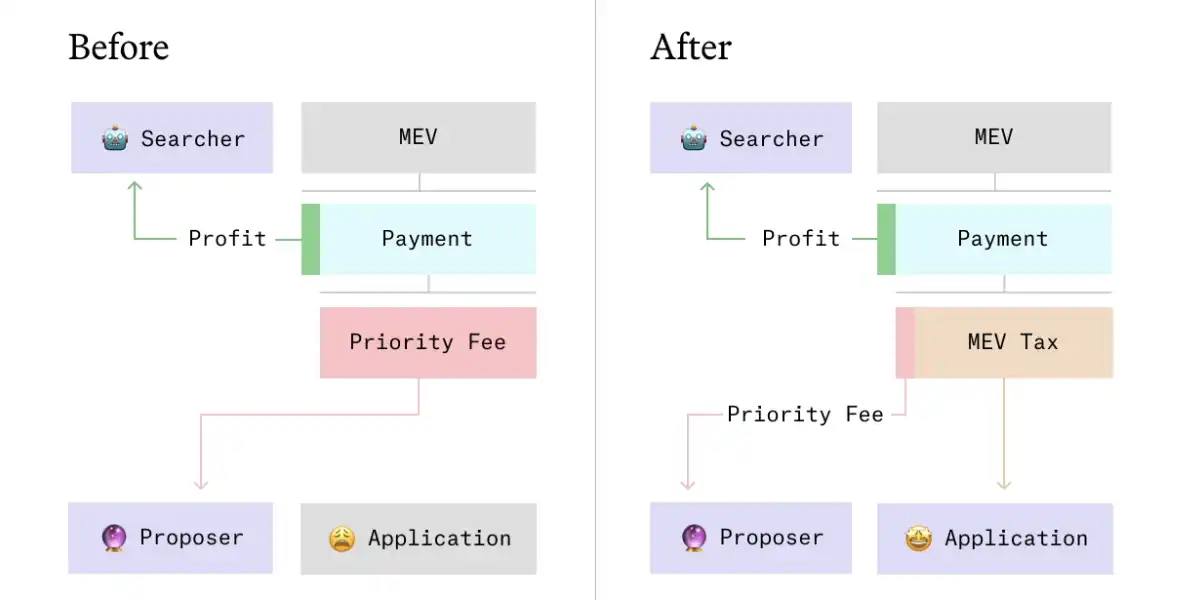

To impose an MEV tax on one of these chains, a smart contract charges a fee that is a function of the transaction’s priority fee. If an application charges a $99 MEV tax for every $1 in priority fees paid by searchers, it can capture 99% of the competitive MEV from that transaction.

MEV taxes are a simple technique that opens up a vast design space. You can think of them as allowing any application on-chain to run its own custom MEV auction, without any off-chain infrastructure of its own—simply plugging into a single shared auction run by block proposers.

We explain how MEV taxes can be used to address three major problems in MEV research:

Decentralized exchange (DEX) routers that optimize prices received by swappers;

Automated market makers (AMMs) that minimize loss versus rebalancing (LVR) experienced by liquidity providers;

Wallets that allow users to capture any "backrun" MEV created by their transactions;

But there’s a catch. MEV taxes only work if block proposers strictly adhere to competitive priority ordering rules, including sorting transactions by priority fee without censoring, peeking at, or delaying any transaction. If block proposers deviate from these rules, they can evade MEV taxes and extract value for themselves. Thus, today, MEV taxes rely on trusted L2 sequencers and may not function at all on Ethereum L1, where block building is dominated by competitive builder auctions that maximize proposer revenue.

Nonetheless, the power and flexibility of MEV taxation suggest that prioritization might be the right choice for platforms currently capable of providing such a service. The relative simplicity of competitive priority ordering suggests there may be a viable way to enforce it in a decentralized manner, without trusting a single sequencer. We hope this article inspires further research into this problem.

Priority Ordering

When someone sends a transaction on Ethereum L1 or an L2, they specify a priority fee, paid to the block proposer. You can imagine this specified as priorityFeePerGas, a number multiplied by gas used in the transaction to yield builderPriorityFee—the total payment in ETH.

The Ethereum protocol does not require transactions in a block to be sorted greedily in descending order by priorityFeePerGas. However, this is a popular way to build blocks—for example, it's the default algorithm used by OP Stack chain sequencers, as well as geth and reth. Priority ordering not only allows traders to effectively express the urgency of their transactions but also naturally passes certain types of MEV to block proposers.

This happens because priority ordering turns competition for MEV into a priority gas auction. When there's an opportunity to profit from interaction with the chain—such as arbitrage between an AMM and a centralized exchange—searchers race to get ahead. If the chain uses priority ordering to determine transaction inclusion and sequencing, searchers compete by setting high priority fees on their transactions.

In a competitive scenario with zero risk profits, the winning searcher should end up paying the full MEV in priority fees. Therefore, if interacting with a contract yields 100 ETH in profit, the first transaction claiming that profit will set a priority fee of 100 ETH. (We discuss some caveats in the limitations section.)

MEV Taxes

Suppose a smart contract wants to capture MEV from any transaction interacting with it. There's extensive research on various application-specific ways smart contracts can attempt to capture their own MEV.

But in fact, we don't necessarily need to know anything about the application. If we know the block was built using competitive priority ordering, then we have a general signal for the amount of MEV in a transaction: the priority fee.

We propose that a smart contract can look at a transaction’s priority fee and charge its own fee as some increasing function of it. For example, a contract might require callers to transfer applicationPriorityFee = 99 * proposerPriorityFee in ETH to the contract.

This additional fee is paid by the searcher sending the transaction, so it affects that searcher’s behavior. If there is 100 MEV in an opportunity, the winning transaction will now set only 1 ETH in priority fee, since this results in a total payment of 100 ETH (1 ETH to the block proposer, 99 ETH to the smart contract). Any higher priority fee would make the transaction unprofitable; any lower would result in losing the opportunity to a competitor setting a higher fee. This means the smart contract has captured 99% of the MEV in the transaction.

We refer to this extra fee charged by the smart contract as an MEV tax. MEV taxes allow applications to hijack priority ordering for their own benefit, enabling them to recapture MEV for their users instead of leaking it to block proposers.

If this fee grows quickly enough as a function of priorityFeePerGas, then proposers receive only a trivial amount of MEV. Since priorityFeePerGas is denominated in wei (one billionth of 1 ETH), we need to handle significant precision. For instance, as long as the MEV tax is sensitive enough that a priorityFeePerGas of 50,000 triggers an excessive tax, the total amount paid to the proposer will be less than $0.01. (5)

However, there is a crucial caveat. As discussed in the “Limitations” section, MEV taxes only work when block proposers follow certain rules (which we call “competitive priority ordering”) rather than deviating from them to maximize their own revenue. Enforcing these rules in a trustless manner remains an open problem.

Single-Application MEV Capture

Here, we outline how, on chains that guarantee block construction using competitive priority ordering, MEV taxes can be used to mitigate three important issues in MEV: enabling DEX interfaces to improve trade execution for swappers, allowing AMMs to reduce arbitrage losses for their LPs, and letting wallets reduce user MEV leakage by selling users’ backrunning rights.

Decentralized Exchange Routers

In intent-based DEX routing protocols like UniswapX and 1inch Fusion, users (Alice) sign swap intents, and searchers compete to route or fill those intents at the best price for Alice.

UniswapX’s current version uses two mechanisms for competition: a Dutch auction, where Alice’s limit price changes over time until a searcher fills it; and an initial off-chain RFQ (request-for-quote) auction to set the starting price of the Dutch auction.

On platforms guaranteeing competitive priority ordering, UniswapX could replace both mechanisms with one: an MEV tax. It could do so by allowing users to sign orders that anyone can immediately fill, but with execution prices defined as a function of transaction priority.

For example, if Alice has a UniswapX order to sell 1 ETH, she could define the execution price of the order as minimumPrice + ($0.01 * priorityFeePerGas). minimumPrice might be a fixed value significantly below the expected current price.

Searchers will compete to fill Alice’s order by submitting transactions. Whichever transaction has the highest priority fee and does not revert will complete the order, which should ensure the swapper gets the best price the searchers can find. (Some exceptions are discussed in the “Limitations” section.)

If Alice’s minimum price is $3,000 and the current price of ETH is $3,500, the winning transaction’s priorityFeePerGas will be approximately 50,000. (Note that in a transaction spending 200,000 gas, this results in only about 10 billion wei (~$0.000035) paid to the block proposer.)

Compared to existing mechanisms used in UniswapX, this has several potential benefits.

Orders using MEV taxes can be filled faster and at better prices than those using Dutch auctions. As discussed in this paper, on-chain Dutch auctions leak value to MEV due to price movements between blocks and may take many blocks to resolve. In contrast, orders using MEV taxes can typically be filled in the next block while capturing the vast majority of MEV.

Unlike off-chain RFQs, the auction for orders using MEV taxes occurs automatically during on-chain transaction execution. This means the winner is only committed to filling the order if the on-chain transaction succeeds. This makes it easier for on-chain liquidity like AMMs to compete with off-chain liquidity, meaning UniswapX can serve as a more effective router for multi-pool systems like Uniswap v4.

AMMs

Typically, AMMs leak value to arbitrageurs who trade based on stale prices at the top of the block, as discussed in the Loss Versus Rebalancing paper. We can use MEV taxes to let AMMs capture MEV. For simplicity, we'll discuss how this works on an AMM without concentrated liquidity. (If you're interested in how this could work with concentrated liquidity, Sorella will soon publish a solution.)

An AMM can capture MEV by charging an additional fee as a function of the transaction’s priority fee, thereby allowing it to auction the right to transact first within a block. There are multiple ways to compute and denominate this fee. We’ll discuss one that could be considered neutral—denominated in units of pool liquidity, sqrt(xy). The winning transaction will be the one that maximally increases pool liquidity.

Instead of enforcing x_end * y_end > x_start * y_start when executing the first transaction on the pool in a block, the pool can enforce (with a as some constant):

x_end * y_end > (sqrt(x_start * y_start) + a*priorityFeePerGas)^2

This formula incentivizes arbitrage traders to trade at the true price, and after the trade, the pool’s mid-price should reflect the true price.

After the first transaction, trades can proceed as on Uniswap v2 with a fixed swap fee. Uninformed traders wanting to transact in the pool without paying the extra MEV tax will set low priority fees.

There are many other ways to implement MEV taxes on AMMs, producing different effects. For example, the MEV tax could be denominated in input or output tokens of the swap, could influence the percentage of swap fees applied by the pool, or could determine a minimum price for user trades. We believe this is an interesting design space worth exploring.

Backrun Auctions

The above describes how to design certain applications to avoid MEV leakage. But what if a wallet wants to help users capture MEV generated by arbitrary transactions interacting with any application—even those without MEV taxes?

For example, when Alice makes a large trade on an AMM, she sometimes creates arbitrage opportunities for “backrunners” to pull the price back. This usually leaks to MEV rather than to Alice.

MEV-Share and MEVBlocker are two protocols allowing users to capture MEV from their transactions, but they rely on complex off-chain auction systems. The Order Flow Auction design space describes some other solutions.

Combined with intent-based smart contract wallets, MEV taxes allow us to build an alternative system to capture backrun MEV for Alice. Suppose instead of creating a transaction to trade on an AMM, Alice signs an intent that anyone can submit to Alice’s smart contract wallet to cause it to perform that action. Alice’s smart contract wallet charges an MEV tax to whoever submits the transaction, payable to Alice.

The searcher submitting Alice’s intent gains exclusive rights to backrun her, since they can automatically execute it within the same transaction. Thus, if competition is strong, all profits from backrunning should flow back to Alice via the MEV tax.

Note that this system does not necessarily protect users from attacks involving front-running their transactions, since a front-running transaction might avoid paying the user an MEV tax. This issue (and some possible mitigations) will be discussed in greater detail in the limitations section below. Nevertheless, this is at least an improvement over systems using public mempools with no mitigation.

Other Use Cases

Beyond these examples, other potential uses of MEV taxes could include almost everything currently using off-chain or Dutch auctions, such as:

Protocols capturing oracle-extractable value they create, such as Oval;

Refinancing auctions for NFT lending protocols like Blend;

Lending protocol liquidations leaking less value than Dutch auctions;

Cross-Application MEV Capture

The above solutions aim to capture MEV from interactions with a single application. But sometimes searchers may extract more value by interacting with multiple applications within the same transaction.

If only one of these applications has an MEV tax, all the MEV in the transaction should go to that application, regardless of how high or low the tax is.

But what if a searcher’s transaction interacts with two applications that both use MEV taxes? For example, suppose some MEV can only be captured by filling one of the aforementioned MEV-tax-charging UniswapX orders against an MEV-tax-paying AMM?

In this case, the relative amounts of excess MEV captured by each application depend on how they set their MEV taxes. If the value collected as MEV tax by app_i is given by the function tax_i(priority), then the priority of the winning transaction can be determined by solving the following equation for priority:

tax_1(priorityPerGas) + tax_2(priorityPerGas) = total MEV

(Technically, we could add a third term for priorityPerGas * gasUsed to account for the priority fee paid to the block proposer, but we’ll ignore this, as it’s negligible under normal circumstances.)

In the simple case where MEV tax is linear in priorityPerGas (so tax_1(priorityPerGas) = a_1 * priorityPerGas), you can solve for the MEV share each application receives:

a_1 * priorityPerGas + a_2 * priorityPerGas = MEV

priorityPerGas = MEV/(a_1 + a_2)

tax_1(priorityPerGas) = (a_1/(a_1+a_2))*MEV

tax_2(priorityPerGas) = (a_2/(a_1+a_2))*MEV

When setting their MEV taxes, applications face a trade-off—higher taxes let them capture a larger share when cross-application MEV occurs, but this means they might miss out on some cross-application MEV if there are competing ways to extract it. For example, if an AMM charges an MEV tax per transaction, MEV-tax UniswapX orders might be more likely to be filled by a different AMM or off-chain filler.

In many cases, there may exist equilibria where two applications design their MEV taxes to share MEV in a way that maximizes their respective profits. For instance, an MEV-tax AMM might want to extract value from a single informed trader near the top of the block, but then wish to provide liquidity at a lower fixed rate to other traders and applications—including those using MEV taxes. In this case, the AMM might set a relatively low MEV tax (e.g., $0.00001 * priorityFeePerGas) so arbitrage occurs early in the block, then charge no MEV tax on subsequent transactions. An application like UniswapX wanting to interact with the AMM could set a higher MEV tax (e.g., $0.01 * priorityFeePerGas) to ensure its transaction is included after the pool has already been arbitraged. Given these relative tax rates, even if there is only $1 of MEV in the UniswapX order and $50,000 in the AMM, the AMM would still be arbitraged first.

We believe this is a rich design space worthy of future research.

Limitations

MEV taxes have complexities and drawbacks, which we believe are interesting areas for future research.

Incentive Incompatibility

MEV taxes are not incentive-compatible for monopolistic block proposers. They only work when there is fair competition for transaction inclusion, which only happens when block proposers follow rules we call “competitive priority ordering,” rather than maximizing their own revenue. Informally, proposed rules include, but are not limited to:

Priority Ordering. Transactions within a block must be ordered in descending order by priorityFeePerGas.

Anti-Censorship. If a block proposer receives transaction t1 during the block period, and the block is either not full or contains some transaction t2 where t2.priorityFeePerGas < t1.priorityFeePerGas, then the block must include t1.

Pre-Transaction Privacy. Block proposers must accept transactions through private endpoints and must not share such transactions with anyone else before inclusion, nor use the content of these transactions as inputs for building their own transactions.

No Last Look. Block proposers must set a clear block time by which they accept transaction submissions from anyone; after this time, they accept no further submissions.

Violating one or more of these properties may undermine the effectiveness of MEV taxes. A censoring block proposer could exclude competing transactions and submit zero-priority transactions for self-benefit, evading most MEV taxes. A block proposer violating pre-transaction privacy could steal MEV from other transactions or observe their priority fees to precisely determine how high their own bid needs to be. A proposer able to submit transactions later gains a free “last look” advantage, potentially causing adverse selection that ultimately stifles competition.

Unfortunately, while the first property is easily enforceable at the protocol layer, enforcing the others in a trustless manner remains an open problem.

Without protocol-level enforcement, reliance falls on trusting a single sequencer committing to these rules not to deviate—and blocks may not follow them if proposers outsource block building to competitive revenue-maximizing auctions (e.g., Ethereum L1’s MEV-Boost).

These issues could be “solved” by a single trusted sequencer committing to competitive priority ordering for block building. Alternatively, they could be addressed via decentralized mechanisms combining consensus, cryptography, and/or trusted execution environments, such as Sorella’s Angstrom, Flashbots’ SUAVE, Leaderless Auctions, Multiplicity, etc.

Full Blocks

An exception to normal MEV tax operation occurs when blocks are completely full. In this case, block proposers may have to drop lower-priority transactions rather than simply including them. Because transactions interacting with MEV-tax applications may have extremely low priority fees, these applications might be crowded out by others that don’t use MEV taxes or use very low ones. However, on chains using mechanisms like EIP-1559 to set a separate base fee, fully filled blocks should be relatively rare. Moreover, considering that some transactions need delay when blocks are full, delaying lower-urgency transactions via higher MEV taxes may be a reasonable outcome.

Reverted Transactions

MEV taxes effectively rely on single-block auctions, where each “bid” is a transaction. One downside of such auctions is that losing bids often result in reverted transactions being included on-chain, paying some base fee and contributing to chain congestion.

This issue could be alleviated if sequencers could fully exclude failed transactions, though even centralized sequencers struggle with this. (It also wouldn’t strictly satisfy the anti-censorship property above, though the definition could be adjusted.) More sophisticated sequencers could optimize this process by allowing transactions to specify which contested auctions they’re participating in, giving sequencers enough information to skip transactions they know will fail.

Leaking User Intent

MEV taxes only work when there is competition among searchers, meaning the opportunity must be somewhat widely known. For applications like AMMs, opportunities are visible on-chain, so this should happen naturally. But for intent-based routing or backrun auctions, it means the application may need to share user intents with searchers.

In some cases, temporary privacy loss from propagating user intent before execution might leak value in ways MEV taxes cannot recover.

For example, suppose Alice wants to use the above backrun auction protocol to buy a low-liquidity token. She posts a signed intent from her smart contract wallet to buy the token on an AMM, setting a certain slippage tolerance. Searchers could competitively push the token’s price up to her slippage tolerance in a high-priority transaction, without filling her order. Then, the winner Bob could fulfill Alice’s intent non-competitively by including and backrunning it in a low-priority transaction, sandwiching Alice’s trade and giving her a worse price while evading her MEV tax. Similar issues could arise with NFT purchases.

Note that such an attack carries risk for Bob, as he cannot guarantee atomicity between buying the token and selling it to Alice. A naive Bob might fall into a “sandwich tear” trap: Alice first publishes an intent to buy a worthless token from herself; Bob buys it to sandwich her trade, but before Bob completes the sandwich, Alice cancels her intent.

Applications can also mitigate this by limiting the set of searchers with whom they share intents and monitoring their behavior, as many existing order flow auctions do.

MEV taxes could also be combined with privacy-preserving builder functionality, as envisioned by Flashbots for SUAVE.

Finally, if Alice believes the cost of sharing intent exceeds the benefits of competitive searching, she can build the transaction herself and submit it directly into a block. As noted above, ideal implementations of competitive priority ordering would provide transaction pre-privacy to block proposers.

Related Discussions

Priority Gas Auctions. The Flash Boys 2.0 paper studied dynamics of priority ordering in decentralized blockchains and coined the term “miner extractable value.” The paper noted that Ethereum miners (when the network used proof-of-work) already ordered transactions by priority, and arbitrageurs relied on this behavior to participate in “priority gas auctions,” bidding for inclusion in the first block, resulting in most DEX arbitrage MEV going to miners.

First-Come, First-Served. Some attempts to mitigate MEV via transaction ordering rules, such as Themis or Arbitrum One’s current sequencer (7), focus on enforcing different ordering rules—first-come, first-served (sometimes called “fair ordering”), where block proposers must order transactions by arrival time.

Priority ordering takes a different approach—treating transactions arriving within a given time window equally and sorting them by declared priority.

First-come, first-served is difficult to define or enforce in real network environments with multiple validators. Even with a single trusted sequencer, it may lead to wasteful latency races and spam. Moreover, MEV taxes may eliminate certain types of MEV that first-come-first-served ordering cannot, such as arbitrage profits from discontinuous “jumps” in asset prices. The potential advantages of priority ordering over first-come-first-served relate somewhat to the advantages of discrete-time exchanges over continuous-time ones, as discussed in Budish, Cramton, Shim (2015).

Meanwhile, while priority ordering may seem to leak value to MEV by default, this article shows how applications can be designed to reclaim it.

Fee Sharing. Blast is an Ethereum L2 that shares portions of priority and base fees with accessed smart contracts.

MEV taxes enable something similar (at least for priority fees) but can be implemented at the application layer on any chain using competitive priority ordering, without requiring special fee-sharing support. They also allow applications to define their tax functions as custom functions of priority fees, offering greater flexibility and potentially enhancing composability for MEV-aware applications.

Trustless Solutions. This article focuses on platform incentives to use competitive priority ordering and methods to leverage it, rather than how to enforce it trustlessly.

Important discussions have previously occurred around each of the other required properties of competitive priority ordering. For example, in Fox, Pai, Resnick (2023), the authors discuss vulnerabilities of on-chain auctions without censorship resistance and describe designs for censorship-resistant auctions using multiple concurrent proposers. However, they do not suggest specific transaction ordering.

Other research exists on trust-minimized block-building mechanisms, including Flashbots’ SUAVE, Sorella’s Angstrom, Leaderless Auctions, Espresso, Offchain Labs’ decentralized Timeboost, and Péter Szilági’s forced public transaction inclusion.

We hope this article encourages L2s to consider using priority ordering (default in OP Stack) and motivates applications to experiment with MEV taxes where supported. We also hope it inspires further research into trust-minimized competitive priority ordering protocols on both L1 and L2.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News