MEV Sandwich Attack Deep Dive: The Deadly Chain from Ordering to Flash Swaps

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

MEV Sandwich Attack Deep Dive: The Deadly Chain from Ordering to Flash Swaps

Understanding MEV and recognizing its risks enables better navigation through this digital world full of opportunities yet hidden dangers.

By: Daii

On Wednesday last week (March 12), a story went viral about a crypto trader who lost $215,000 in a single MEV attack.

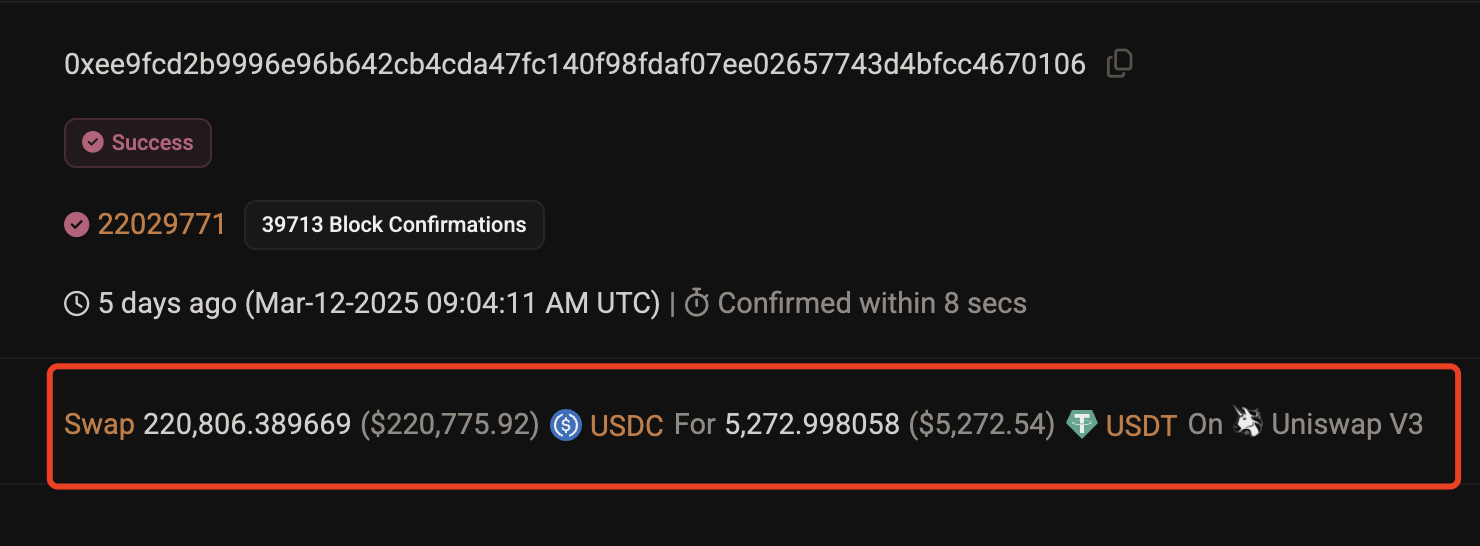

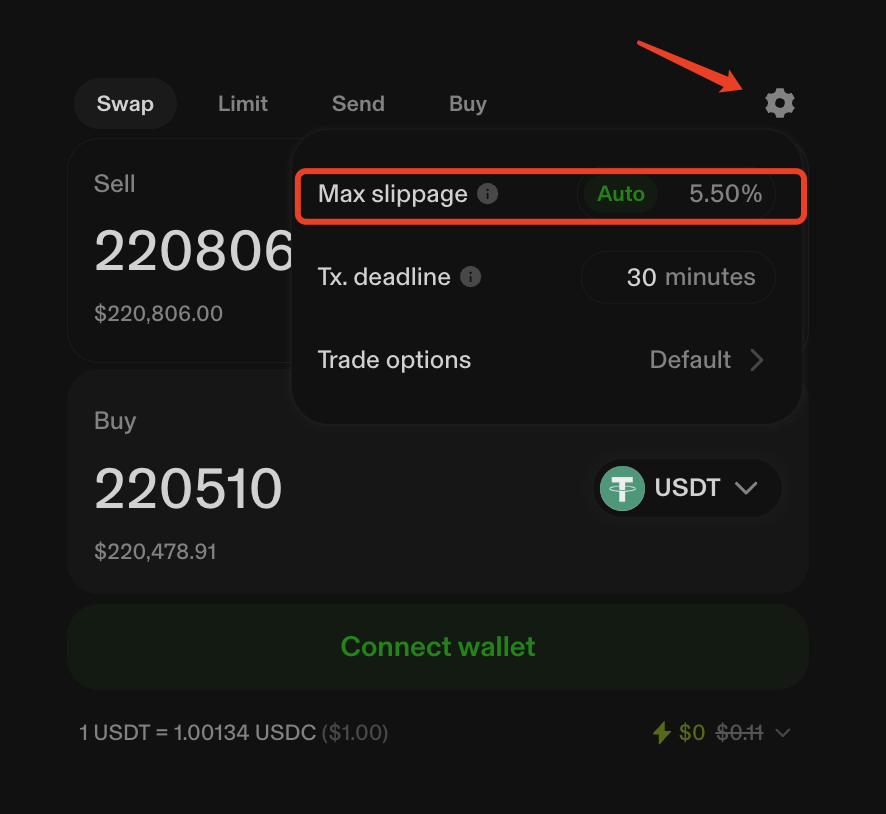

In short, the user intended to swap $220,800 worth of USDC stablecoin for an equivalent amount of USDT on a Uniswap v3 pool, but ended up receiving only 5,272 USDT—losing $215,700 in just seconds. See the image below.

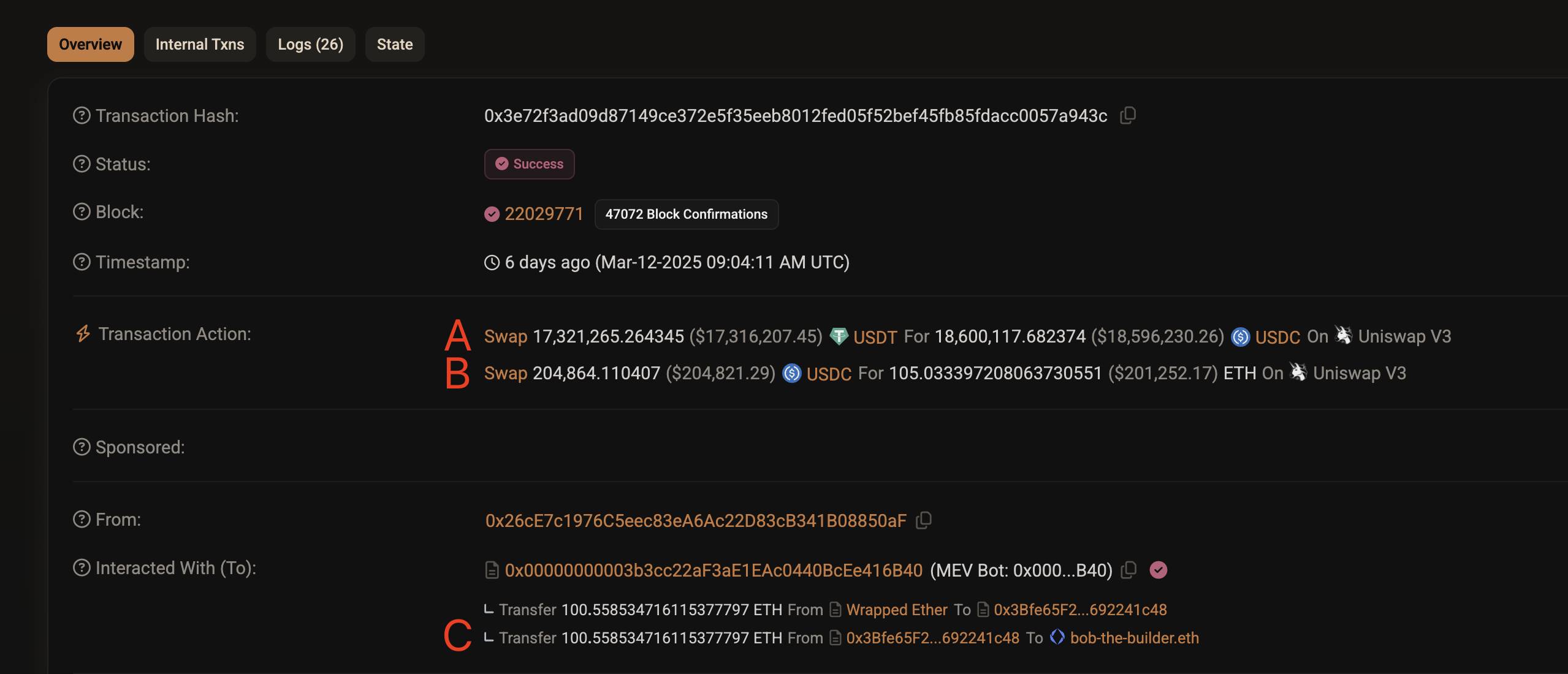

The above image shows a screenshot of the on-chain transaction record. The root cause of this disaster was falling victim to the notorious "sandwich attack" in the blockchain world.

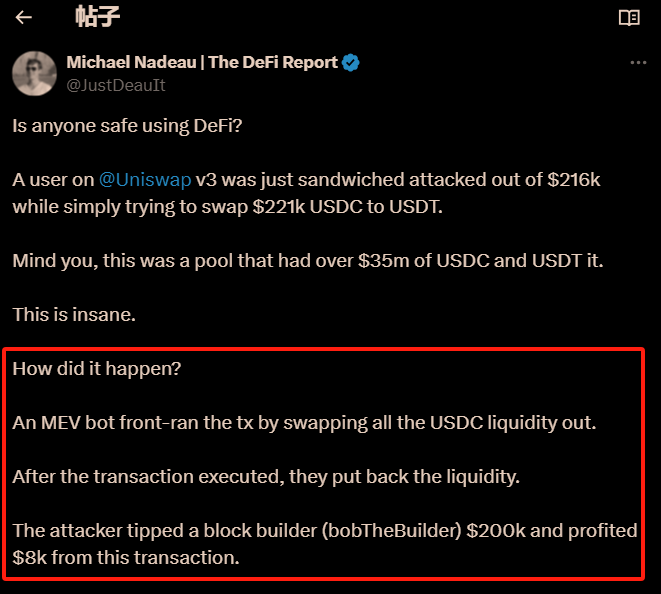

Michael (see above) was the first to disclose this MEV attack. He explained:

An MEV bot front-ran the tx by swapping all the USDC liquidity out. After the transaction executed, they put back the liquidity. The attacker tipped a block builder (bobTheBuilder) $200k and profited $8k from this transaction.

There is a typo in the text above: the MEV attack bot swapped out a large amount of USDT, not USDC.

However, after reading his explanation and news reports, you might still be confused due to many unfamiliar terms such as sandwich attack, front-running transactions, restoring liquidity, tipping a block builder, etc.

Today, using this MEV attack as an example, we will break down its entire process and take you deep into the dark world of MEV.

First, let’s clarify what MEV is.

1. What is MEV?

MEV originally stood for Miner Extractable Value—the extra profit miners could earn by reordering, inserting, or excluding transactions within blockchain blocks. Such manipulation could lead ordinary users to pay higher costs or receive worse trade prices.

As blockchain networks like Ethereum transitioned from Proof-of-Work (PoW) to Proof-of-Stake (PoS) consensus mechanisms, the power to order transactions shifted from miners to validators. Consequently, the term evolved from "Miner Extractable Value" to "Maximal Extractable Value."

Despite the name change, the core concept—extracting value through transaction ordering manipulation—remains unchanged.

The description above may still sound technical. Simply remember: MEV exists because miners (historically) and now validators have the right to sort transactions in the mempool. This sorting happens once per block; currently, Ethereum produces a block roughly every 11 seconds, meaning this privilege is exercised approximately every 11 seconds. This particular MEV attack was also enabled through validator-controlled transaction ordering.

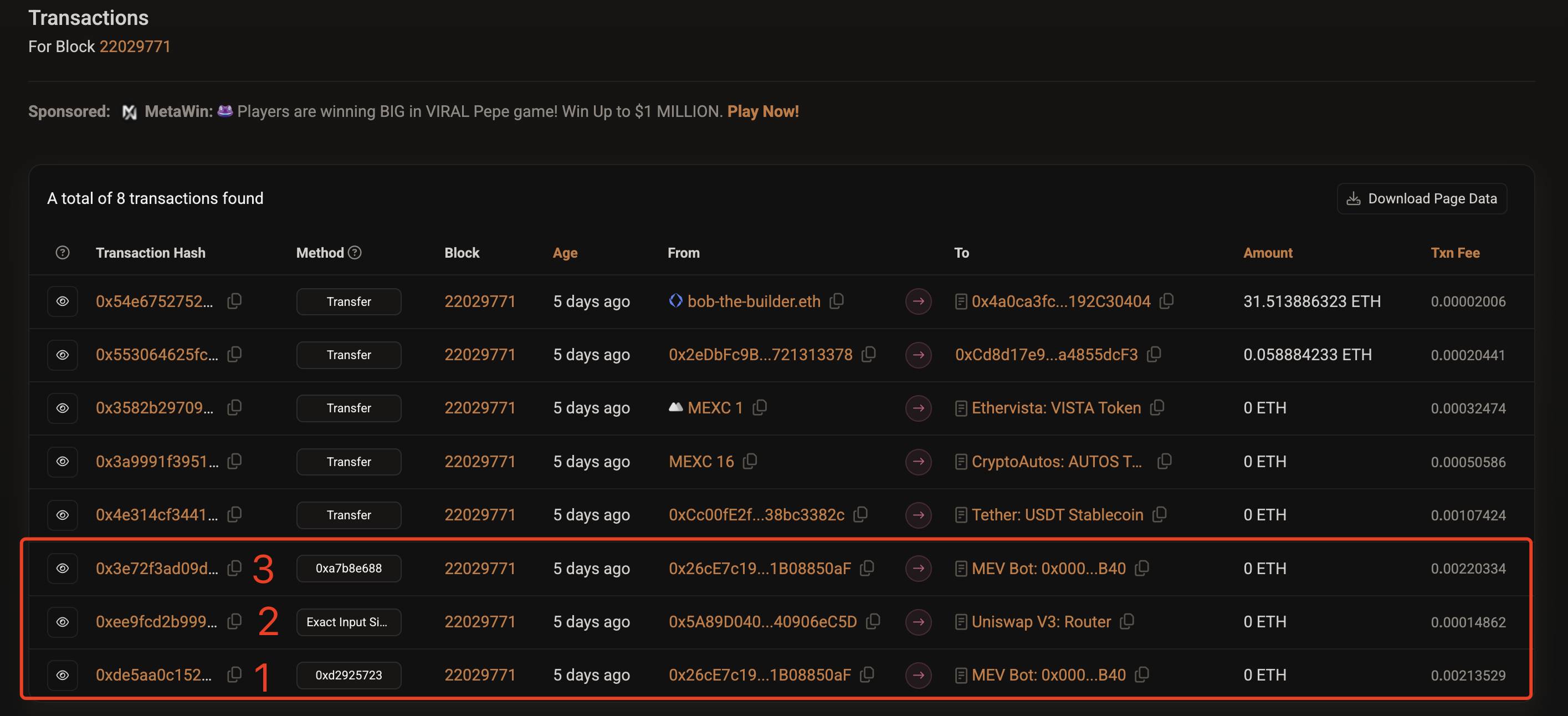

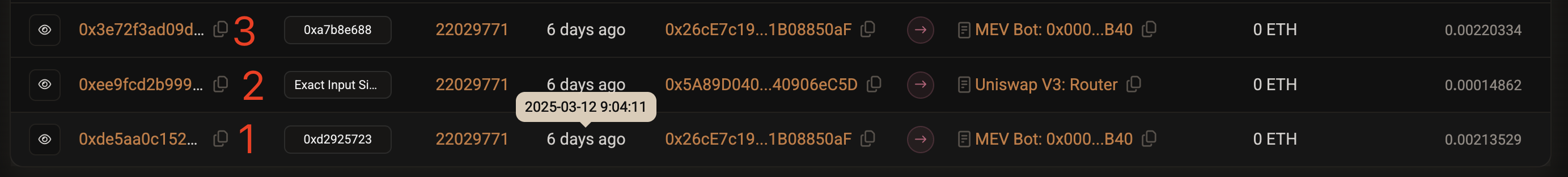

Clicking this link reveals the contents of Block #22029771 related to this attack, as shown below.

Note that transactions 1, 2, and 3 in the image above constitute the MEV attack described at the beginning of this article—arranged precisely by the validator (bobTheBuilder). Why was this possible?

2. How Does MEV Work?

To understand how MEV works, we need to first grasp how blockchains record and update information.

2.1 Blockchain State Update Mechanism

A blockchain can be viewed as a continuously growing ledger recording all transactions. Its state—including account balances and token reserves in pools like Uniswap—is determined by prior transactions.

When a new block is added to the chain, all transactions within it are executed sequentially according to their order in the block. Each transaction execution updates the global state of the blockchain accordingly.

This means not only the sequence of blocks matters, but also the order of transactions within each block. So how is the intra-block transaction order decided?

2.2 Validators Control Transaction Ordering

When a user initiates a transaction on a blockchain network—for instance, swapping USDC for USDT via Uniswap—it is first broadcast to network nodes. After preliminary validation, the transaction enters a holding area called the "mempool," where unconfirmed transactions await inclusion in the next block.

Historically, miners (in PoW systems) and now validators (in PoS systems) have the authority to select transactions from the mempool and determine their order in the upcoming block.

The sequence of transactions within a block is critical. Before a block is finalized and added to the blockchain, its transactions execute in the order set by the validator (e.g., bobTheBuilder). This means if multiple transactions interact with the same pool within one block, their execution order directly affects the outcome of each trade.

This capability allows validators to prioritize certain transactions, delay or exclude others, or even insert their own trades to maximize profits.

In this case, the transaction order was crucial—any deviation would have prevented the attack from succeeding.

2.3 Transaction Order in This MEV Attack

Let’s briefly examine the three transactions involved in this MEV attack:

-

Transaction 1 (Attacker's First Move): Executed before the victim’s trade. Its purpose is typically to push up the price of the token the victim wants to buy.

-

Transaction 2 (Victim's Trade): Executes after the attacker’s first move. Due to the previous manipulation, the pool price is unfavorable—the victim receives far fewer USDT than expected for their USDC.

-

Transaction 3 (Attacker's Exit): Executes after the victim’s trade. It capitalizes on the price changes caused by the victim’s trade to secure profits.

The validator responsible for arranging these transactions in the 1-2-3 order was bob-The-Builder.eth. Naturally, bobTheBuilder wasn’t acting altruistically—he earned over 100 ETH from participating in this arrangement, while the MEV attacker made only $8,000. Their revenue came directly from the victim’s second transaction.

In short, the attacker (an MEV bot) colluded with the validator (bobTheBuilder), causing the victim to lose $215,000—of which $8,000 went to the attacker and $200,000 (over 100 ETH) to the validator.

Their method has a vivid name: the sandwich attack. Next, we’ll walk through each transaction step-by-step to fully demystify how this complex MEV strategy works.

3. Full Breakdown of the Sandwich Attack

The term “sandwich attack” comes from the fact that the attacker places two transactions (Transaction 1 and 3) around the victim’s transaction (Transaction 2), forming a structure resembling a sandwich (see image above).

-

Transactions 1 and 3 serve distinct roles. In simple terms: Transaction 1 sets up the attack, and Transaction 3 collects the profits. Here’s how it unfolds:

-

3.1 Transaction 1: Increasing the Price of USDT

-

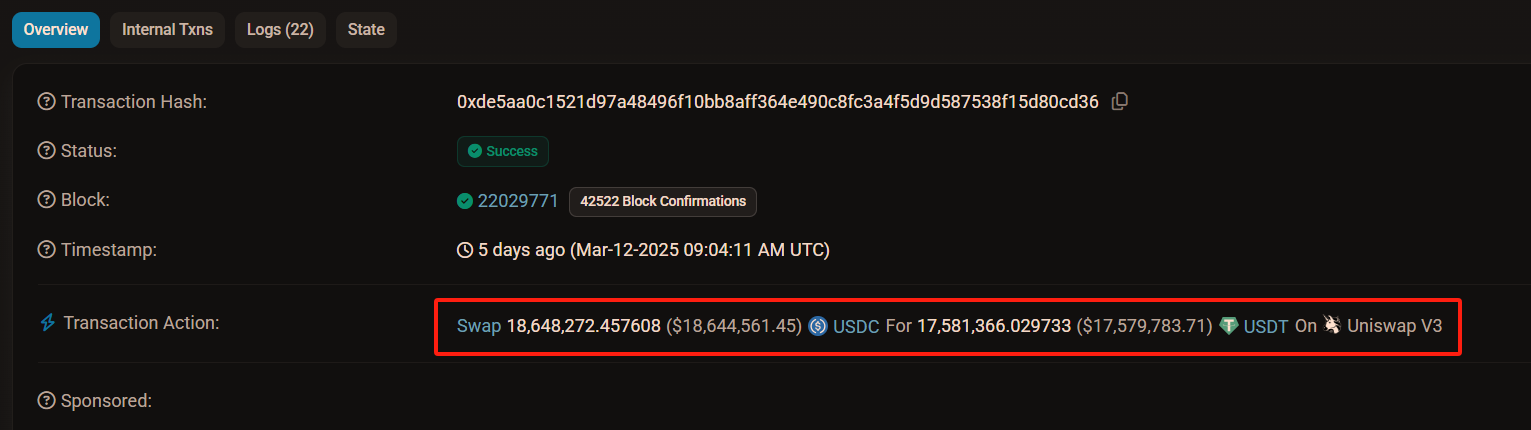

Clicking the link for Transaction 1 reveals its details. The attacker sharply increased the price of USDT by using 18.65 million USDC to withdraw all 17.58 million USDT from the pool (see image below).

After this, the liquidity pool contained mostly USDC and very little USDT. Assuming pre-attack reserves were around 19.8 million USDC and USDT respectively, post-Transaction 1, the pool held only ~2.22 million USDT (=19.8M - 17.58M), while USDC surged to ~38.45 million (=19.8M + 18.65M).

At this point, the exchange rate between USDC and USDT was no longer close to 1:1—it became approximately 17:1, meaning 17 USDC were needed to get 1 USDT. (Note: This is approximate, as Uniswap V3 uses concentrated liquidity rather than uniform distribution.)

One important clarification: the attacker did not actually deploy $18.65 million of their own USDC. Only about $1.09 million—less than 6%—was real capital. We’ll explain how this was possible later.

3.2 Transaction 2: Victim Attempts to Swap 220K USDC for USDT

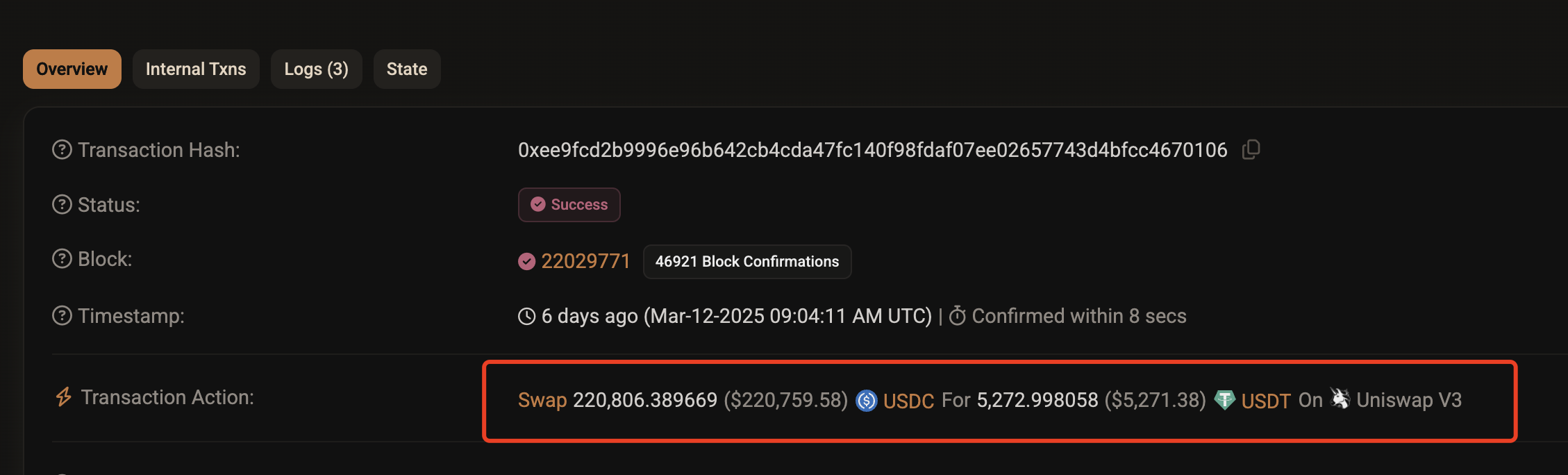

Clicking the link for Transaction 2 leads to the following view:

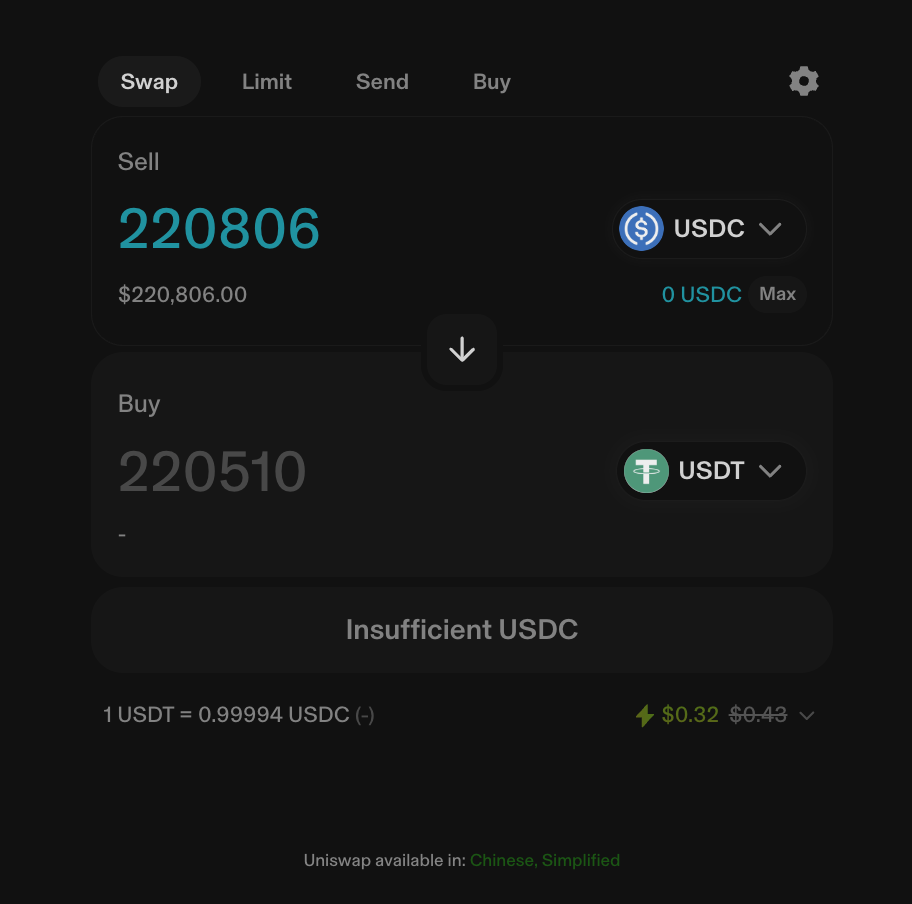

As seen above, due to Transaction 1, the victim received only 5,272 USDT for 220,000 USDC—unknowingly losing over 170,000 USDT. Why “unknowingly”? If the victim used Uniswap’s frontend, they would have seen a screen like this when submitting the trade:

You’ll notice the interface guarantees the user at least 220,000 USDT. The reason they ended up with just over 5,000 USDT was massive slippage—over 90%. However, Uniswap enforces a default maximum slippage limit of 5.5%, as shown below:

This implies that if the victim had traded through Uniswap’s official frontend, they should have received at least 208,381 USDT (=220,510 × 94.5%). You might wonder why the on-chain record indicates this occurred on “Uniswap V3.”

The answer lies in the separation between frontend and backend in blockchain transactions. “Uniswap V3” refers to the public USDC-USDT liquidity pool, which any third-party frontend can access and use for trading.

Because of this, some speculate the victim may not be an ordinary user—if so, such extreme slippage would be nearly impossible under normal conditions. There’s even speculation the victim might have been involved in money laundering via MEV attacks. We’ll explore that possibility another time.

3.3 Transaction 3: Profit Realization and Payout

Clicking the link reveals the details of Transaction 3 (shown above). Let’s analyze parts A, B, and C separately:

-

Transaction A: Restores normal liquidity by exchanging 17.32 million USDT back for 18.6 million USDC;

-

Transaction B: Prepares profit distribution by converting part of the proceeds—204,000 USDC—into 105 ETH;

-

Transaction C: Distributes profits by sending 100.558 ETH to validator bob-The-Builder.eth as a fee.

With that, the sandwich attack concludes.

Now, let’s address a key question raised earlier: How did the attacker manage to pull off an $18 million-level manipulation using only $1.09 million in capital?

4. How Did the Attacker Execute an $18 Million Pool Manipulation with Just $1.09 Million?

The reason the attacker could leverage just $1.09 million in USDC to manipulate a pool worth millions lies in a unique and powerful mechanism in the blockchain ecosystem: Uniswap V3’s Flash Swap.

4.1 What Is a Flash Swap?

In short:

A flash swap allows a user to withdraw assets from a Uniswap pool and repay them—plus fees or equivalent assets—within the same transaction.

As long as the entire operation completes atomically within one transaction, Uniswap permits this “take-first, pay-later” model. Crucially, everything must happen within a single transaction. This design ensures platform security:

-

Zero-risk lending: Users can temporarily borrow funds from the pool without collateral, provided they repay before the transaction ends.

-

Atomicity: The entire operation must either fully succeed (with repayment) or completely fail (transaction reverted).

Flash swaps were initially designed to enable efficient on-chain arbitrage—but unfortunately, they’ve also become a powerful tool for MEV attackers to manipulate markets.

4.2 How Did the Flash Swap Enable the Attack?

Let’s walk through the diagram step-by-step to see how the flash swap facilitated this attack (see image below).

-

F1: The attacker borrowed 1.09 million USDC from Aave using 701 WETH as collateral;

-

F2: The attacker initiated a flash swap, withdrawing 17.58 million USDT from the Uniswap pool (no upfront payment required), temporarily increasing their balance by 17.58 million USDT;

-

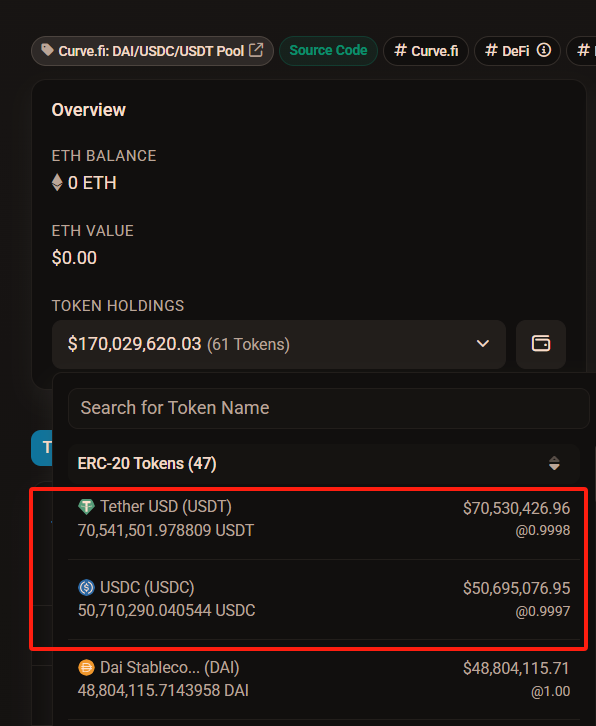

F3: The attacker quickly swapped the 17.58 million USDT into 17.55 million USDC via Curve’s pool—reducing USDT by 17.58 million and increasing USDC by 17.55 million. As shown below, the attacker chose Curve due to its deep liquidity: over 70.54 million USDT and 50.71 million USDC, resulting in low slippage.

-

F4: The attacker used the 17.55 million USDC from Curve plus the original 1.09 million USDC borrowed from Aave (totaling ~18.64 million USDC) to repay the Uniswap flash swap. Flash swap complete.

After this transaction (Transaction 1), the attacker’s net loss was exactly 1.09 million USDC—since only 17.55 million of the repaid 18.64 million USDC came from Curve, the remaining 1.09 million was their own capital.

You might notice: this transaction alone cost the attacker $1.09 million. But in Transaction 3, using the same flash swap technique, they not only recovered that $1.09 million but also made over $200,000 in profit.

Let’s now analyze Transaction 3 step by step using actual data:

-

K1: The attacker used a flash swap to withdraw 18.6 million USDC from Uniswap;

-

K2: Using 17.3 million of that USDC, they swapped back into 17.32 million USDT;

-

K3: They returned the 17.32 million USDT to Uniswap to settle the flash swap. Note: K2 cost only 17.3 million USDC but yielded 17.32 million USDT. Of the remaining 130 million USDC (18.6M - 17.3M), 109 million covered the initial capital, leaving ~210,000 USDC as pure profit.

-

K4: The attacker repaid Aave, reclaimed their 701 WETH, converted 200,000 USDC into 105 ETH, sent 100.558 ETH (~$200,000) to validator bob-The-Builder.eth as a bribe, and kept less than $10,000 in profit.

You might wonder: why would the attacker willingly give up $200,000 in profits to the validator?

4.3 Why Pay a $200,000 “Tip”?

This isn’t generosity—it’s a necessary condition for the success of a sandwich attack.

The key to the attack’s success is precise control over transaction ordering, which is controlled entirely by the validator (bobTheBuilder).

The validator not only ensures the victim’s transaction is sandwiched between the attacker’s two moves, but more importantly, prevents competing MEV bots from interfering or hijacking the opportunity.

Therefore, the attacker prefers to sacrifice most of the profit to guarantee success, keeping only a small share for themselves.

It’s worth noting that MEV attacks do carry costs—flash swaps on Uniswap and trades on Curve incur fees, though typically very low (around 0.01–0.05%), making them negligible compared to the profits gained.

Finally, defending against MEV attacks is relatively straightforward: set a tight slippage tolerance (e.g., under 1%) and split large trades into smaller ones. So there’s no need to avoid DEX trading altogether.

Conclusion: A Warning and Insight from the Dark Forest

This $215,000 MEV attack starkly illustrates the harsh "dark forest" law of the blockchain world. It vividly reveals the complex game of exploiting systemic loopholes for profit within decentralized, permissionless environments.

At a deeper level, MEV exemplifies the double-edged nature of blockchain transparency and programmability.

On one hand, all transactions are publicly visible, enabling traceability and analysis of malicious behavior.

On the other hand, the deterministic execution and intricate logic of smart contracts create opportunities for sophisticated actors to exploit.

This is not mere hacking—it’s a profound understanding and strategic use of blockchain’s foundational mechanics. It tests the robustness of protocol design and challenges participants’ risk awareness.

Only by understanding MEV and recognizing its risks can we better navigate this digital realm full of opportunities yet fraught with hidden dangers.

And that is precisely the effect I aim to achieve with this article.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News