Advanced Formal Verification of Zero-Knowledge Proofs: An In-Depth Analysis of Two ZK Vulnerabilities

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Advanced Formal Verification of Zero-Knowledge Proofs: An In-Depth Analysis of Two ZK Vulnerabilities

In this article, we will focus on the perspective of vulnerability discovery, analyze specific vulnerabilities identified during audit and verification processes, and discuss the lessons learned.

Author: CertiK

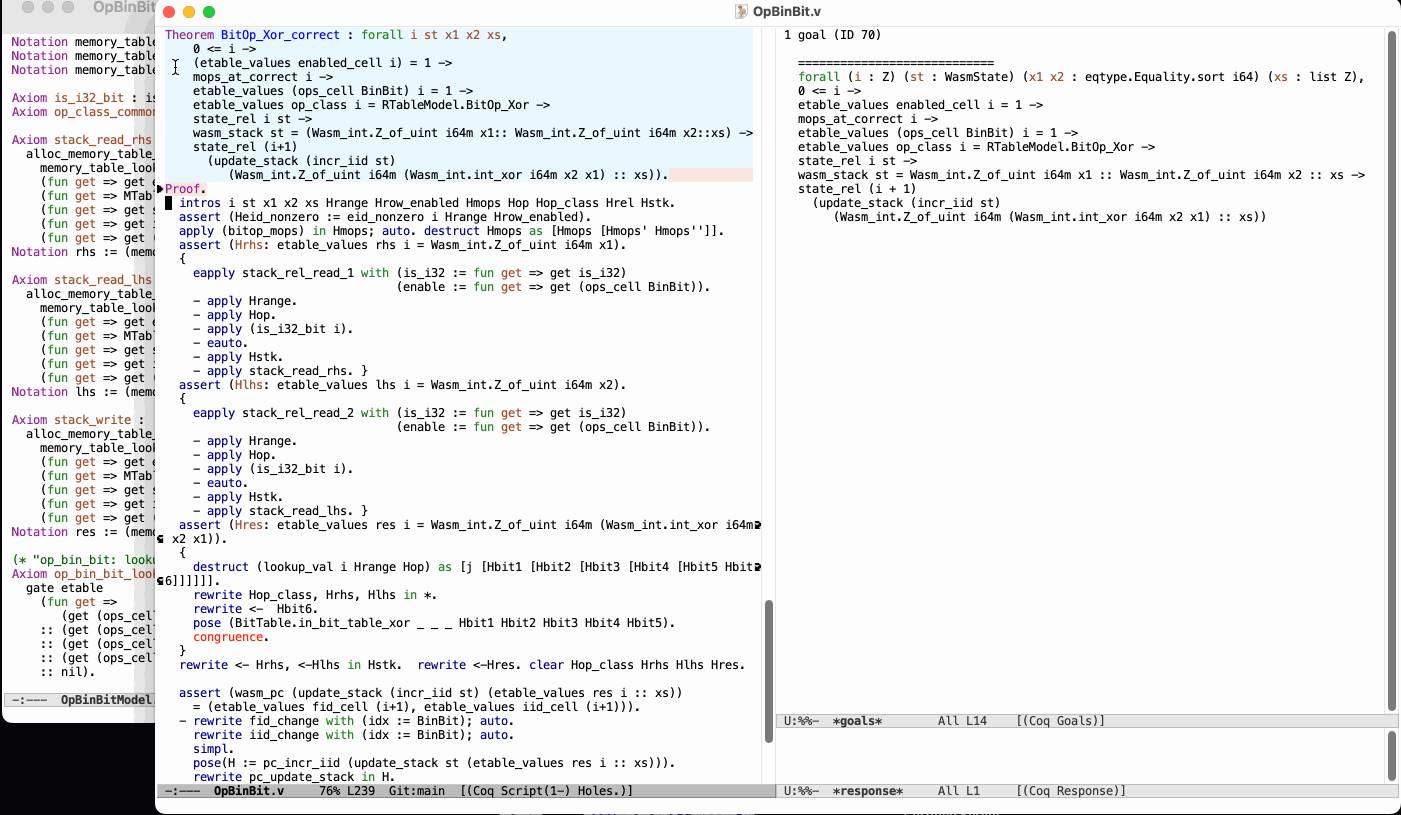

In previous articles, we discussed advanced formal verification of zero-knowledge proofs: how to verify a single ZK instruction. By formally verifying each zkWasm instruction, we can fully ensure the technical security and correctness of the entire zkWasm circuit. In this article, we will take the perspective of vulnerability discovery, analyzing specific vulnerabilities identified during audit and verification processes, along with the lessons learned. For a general discussion on advanced formal verification of zero-knowledge proof (ZKP) blockchains, please refer to the article "Advanced Formal Verification of Zero-Knowledge Proof Blockchains."

Before discussing ZK vulnerabilities, let's first understand how CertiK conducts ZK formal verification. For complex systems like a zero-knowledge virtual machine (zkVM), the first step in formal verification (FV) is clearly defining what needs to be verified and its properties. This requires a comprehensive review of the ZK system’s design, code implementation, and test setup. This process overlaps with conventional auditing, but differs in that it must establish verification goals and properties after the review. At CertiK, we call this verification-oriented auditing. Auditing and verification are typically integrated. For zkWasm, we conducted both auditing and formal verification simultaneously.

What Is a ZK Vulnerability?

The core feature of zero-knowledge proof systems is enabling short cryptographic proofs of offline or private computations (e.g., blockchain transactions) to be passed to a ZK verifier for checking and confirmation, assuring that the computation did indeed occur as claimed. In this context, a ZK vulnerability allows hackers to submit forged ZK proofs purporting to validate false transactions, which the ZK proof checker would then accept.

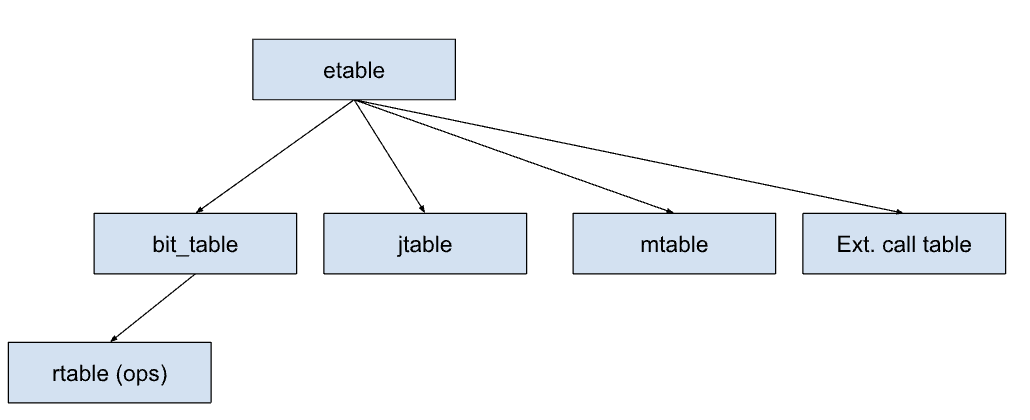

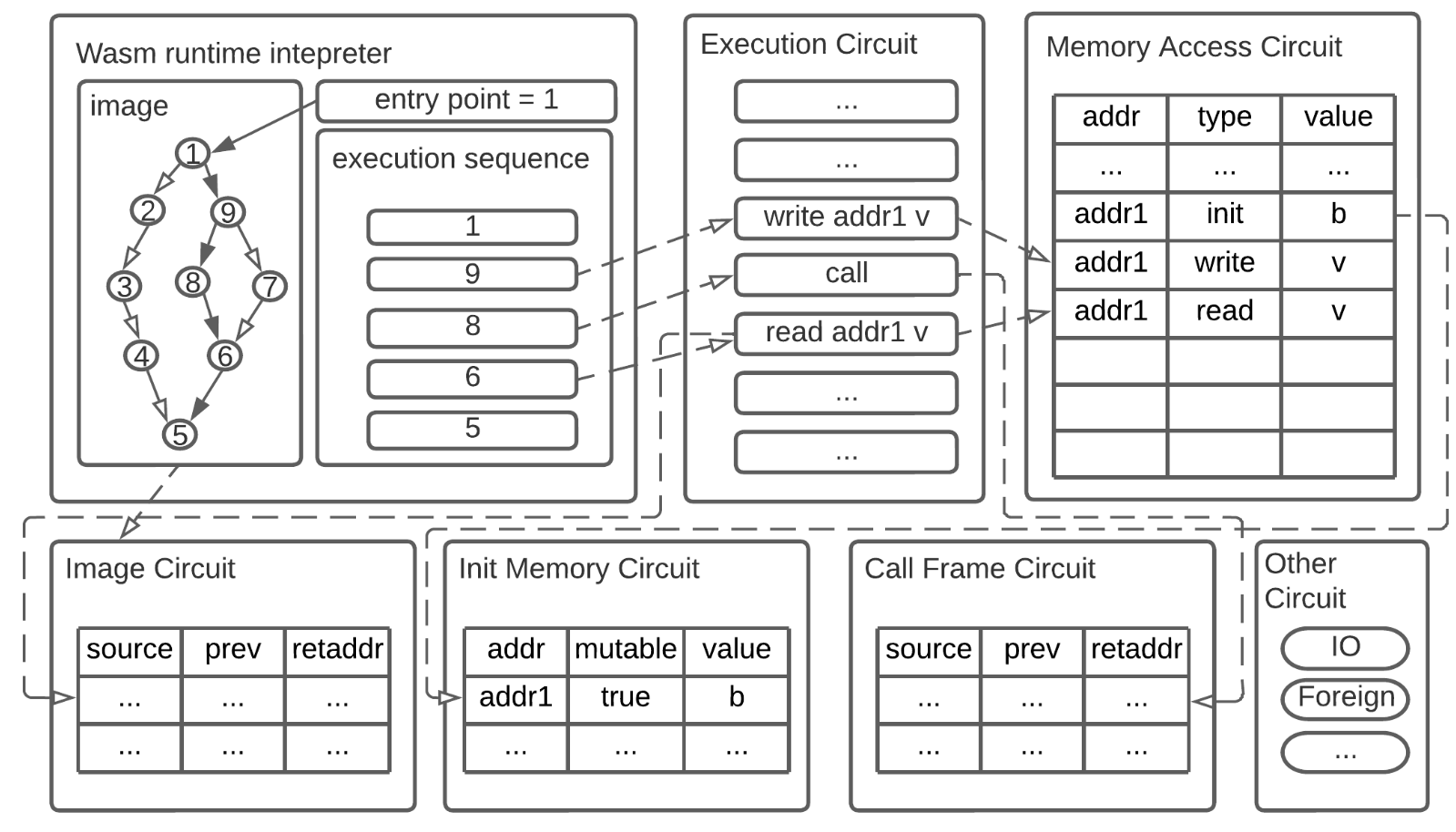

For a zkVM prover, the ZK proof process involves running a program, generating an execution trace for each step, and converting the trace data into a set of numeric tables (a process called "arithmetization"). These numbers must satisfy a set of constraints (the "circuit"), including relational equations between specific table cells, fixed constants, database lookup constraints across tables, and polynomial equations (also known as "gates") that must hold between each pair of adjacent rows in the tables. On-chain verification can thus confirm the existence of a table satisfying all constraints, while never revealing the actual values within the table.

zkWasm Arithmetization Table

The accuracy of every constraint is crucial. Any error—whether a constraint is too weak or missing—could allow hackers to submit misleading proofs where the tables appear to represent a valid smart contract execution, but actually do not. Compared to traditional VMs, the opacity of zkVM transactions amplifies these vulnerabilities. In non-ZK chains, transaction computation details are publicly recorded on blocks; in contrast, zkVMs do not store these details on-chain. This lack of transparency makes it difficult to determine exactly how an attack occurred—or even whether an attack has happened at all.

The ZK circuits implementing zkVM instruction rules are extremely complex. For zkWasm, the ZK circuit implementation involves over 6,000 lines of Rust code and hundreds of constraints. Such complexity often implies multiple vulnerabilities may remain undiscovered.

zkWasm Circuit Architecture

Indeed, through our auditing and formal verification of zkWasm, we discovered several such vulnerabilities. Below, we will discuss two representative examples and examine their differences.

Code Vulnerability: Load8 Data Injection Attack

The first vulnerability involves the Load8 instruction in zkWasm. In zkWasm, heap memory reads are performed using a set of LoadN instructions, where N is the size of the data to be loaded. For example, Load64 should read 64 bits of data from a zkWasm memory address. Load8 should read 8 bits of data (one byte) from memory and pad it with zeros to form a 64-bit value. Internally, zkWasm represents memory as an array of 64-bit words, so it must "extract" part of a memory word. To achieve this, four intermediate variables (u16_cells) are used, which together form the complete 64-bit loaded value.

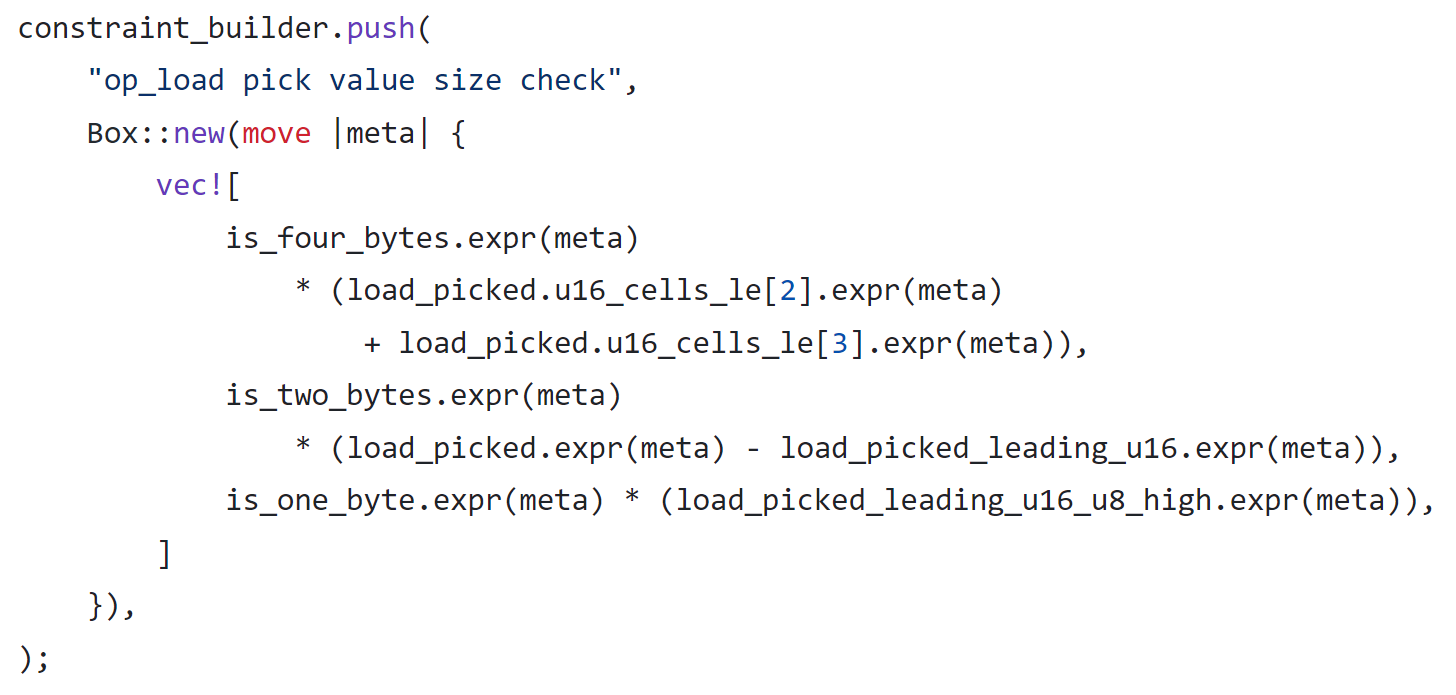

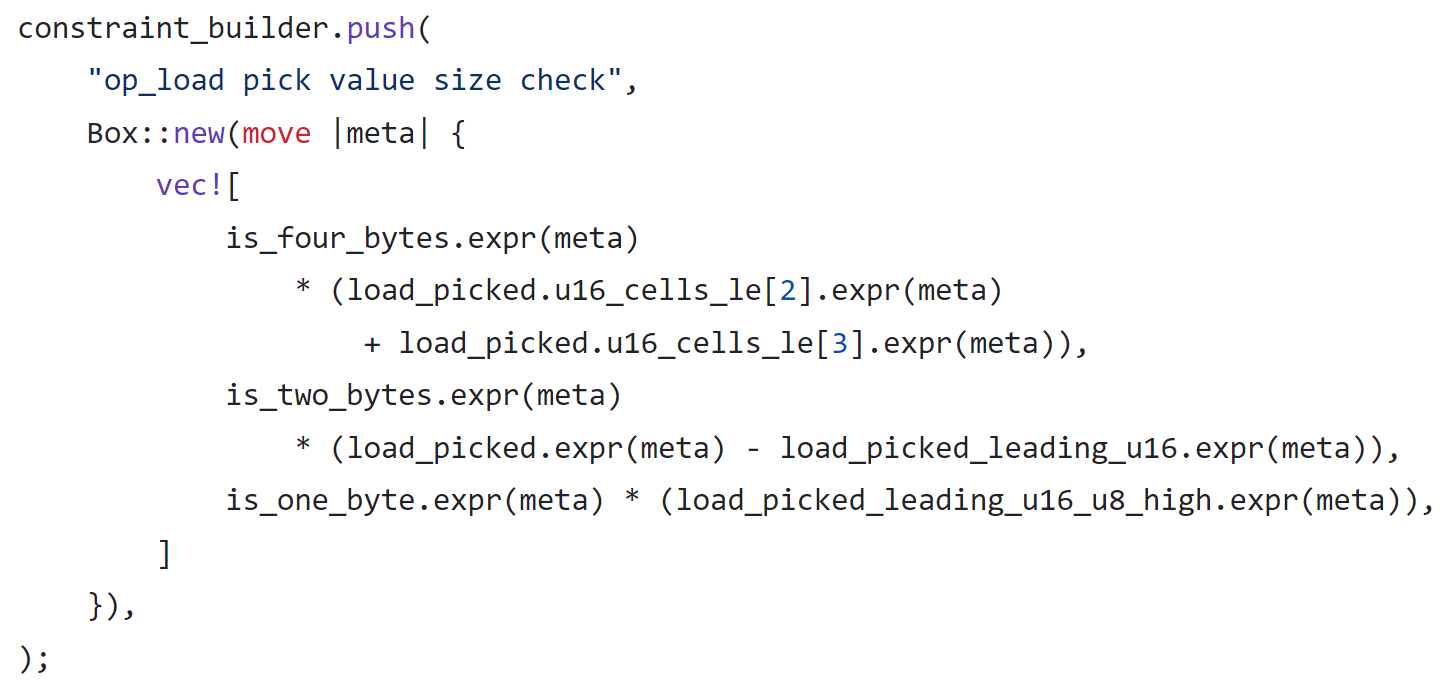

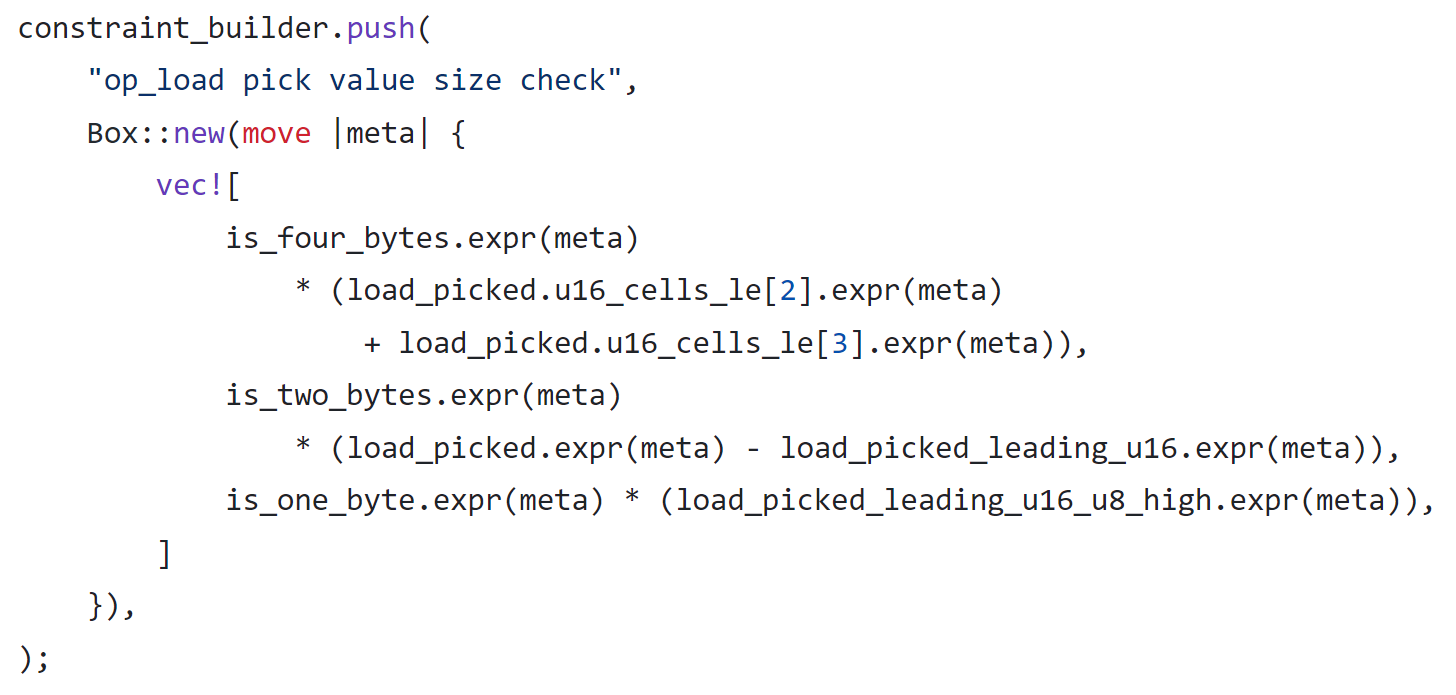

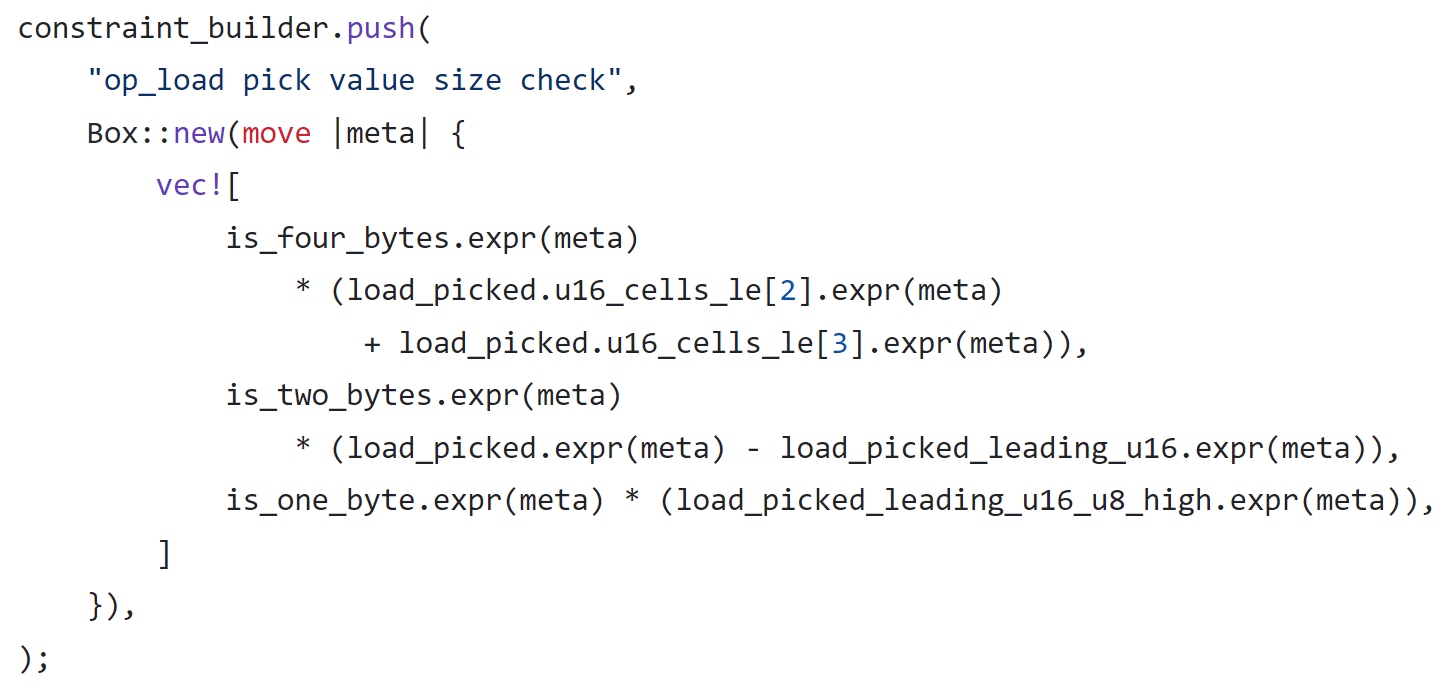

The constraints for these LoadN instructions are defined as follows:

This constraint branches into three cases: Load32, Load16, and Load8. Load64 has no constraint because memory units are exactly 64 bits. For Load32, the code ensures the high 4 bytes (32 bits) of the memory word must be zero.

For Load16, the high 6 bytes (48 bits) of the memory word must be zero.

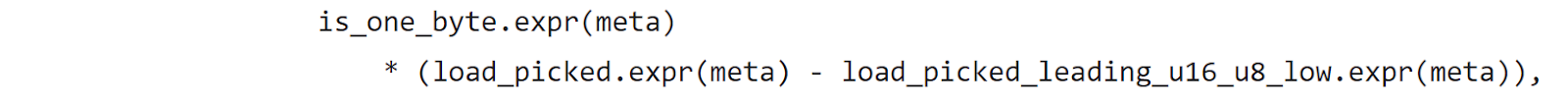

For Load8, the high 7 bytes (56 bits) of the memory word should be required to be zero. Unfortunately, this was not enforced in the code.

As you can see, only bits 9–16 are constrained to zero. The other high 48 bits can take arbitrary values yet still be disguised as "read from memory."

By exploiting this vulnerability, hackers could tamper with a legitimate execution sequence’s ZK proof so that the Load8 instruction loads these unexpected bytes, causing data corruption. Furthermore, by carefully arranging surrounding code and data, attackers might trigger false executions and transfers, thereby stealing data and assets. Such forged transactions could pass the zkWasm checker’s validation and be incorrectly accepted by the blockchain as genuine.

Fixing this vulnerability is actually quite simple.

This vulnerability represents a class of ZK vulnerabilities known as "code vulnerabilities," as they originate from coding errors and can be easily fixed with minor local code modifications. As you might agree, these vulnerabilities are also relatively easier to spot.

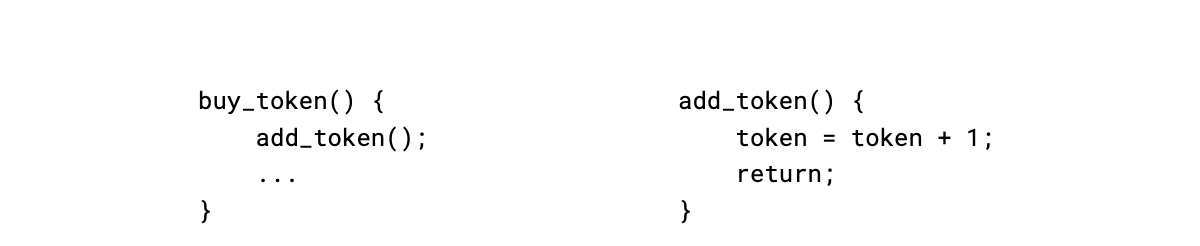

Design Vulnerability: Fake Return Attack

Let us now examine another vulnerability, this time concerning function calls and returns in zkWasm. Call and return are fundamental VM instructions allowing one execution context (e.g., a function) to invoke another and later resume its own execution after the callee finishes. Each call is expected to eventually have a corresponding return. The dynamic data tracked during the call-return lifecycle in zkWasm is known as a "call frame." Since zkWasm executes instructions sequentially, all call frames can be ordered based on their occurrence during execution. Below is an example of call/return code running on zkWasm.

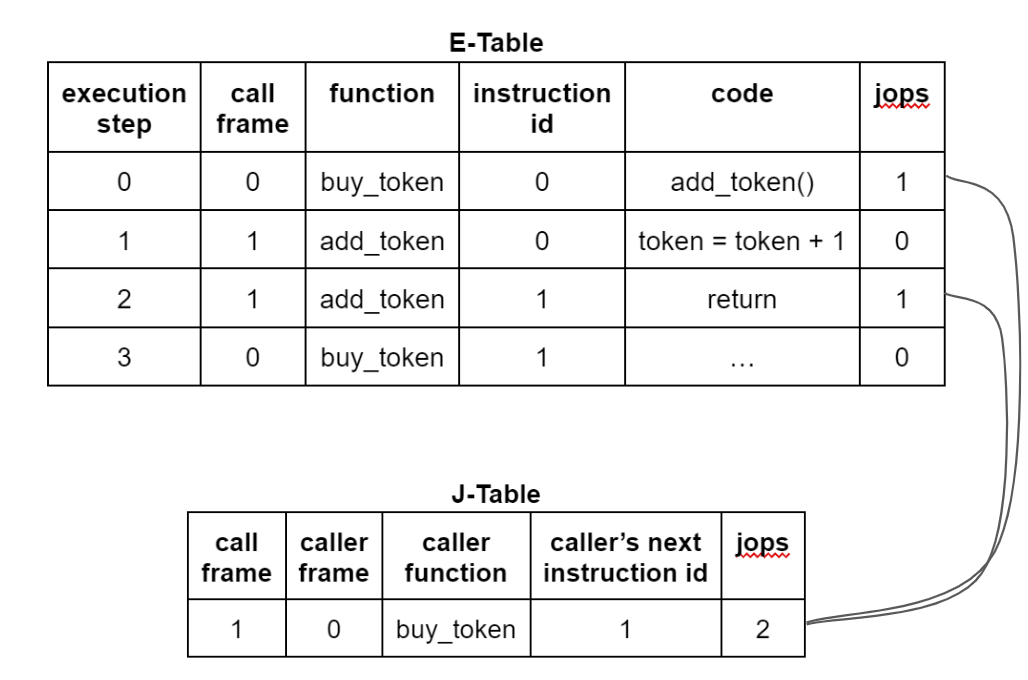

Users can call the buy_token() function to purchase tokens (possibly by paying or transferring something valuable). One of its core steps is calling add_token() to increment the token account balance by 1. Since the ZK prover itself does not support a call frame data structure, execution tables (E-Tables) and jump tables (J-Tables) are used to record and track the full history of these call frames.

The above figure illustrates the process of buy_token() calling add_token(), and then returning from add_token() back to buy_token(). As shown, the token account balance increases by 1. In the execution table, each execution step occupies one row, including the current call frame number, the current context function name (for illustration only), the current instruction number within the function, and the current instruction stored in the table (for illustration only). In the jump table, each call frame occupies one row, storing the caller frame number, the caller function context name (for illustration only), and the next instruction location in the caller frame (so it can return correctly). Both tables include a jops column tracking whether the current instruction is a call/return (in the execution table) or the total number of call/return instructions occurring in that frame (in the jump table).

As expected, each call should have one corresponding return, and each frame should experience exactly one call and one return. In the above figure, frame 1 in the jump table has a jops value of 2, corresponding to the two jops=1 entries in rows 1 and 3 of the execution table. Everything appears normal.

However, there is actually a problem: although one call and one return result in a jops count of 2, so do two calls or two returns. Having two calls or two returns per frame may sound absurd, but remember—this is exactly what hackers aim to exploit by breaking expected behaviors.

You might now feel a bit excited—but have we truly found the issue?

It turns out that two calls are not problematic, because constraints in the execution and call tables prevent two calls from being encoded in the same frame’s rows—each call generates a new frame number, specifically the current call frame number plus one.

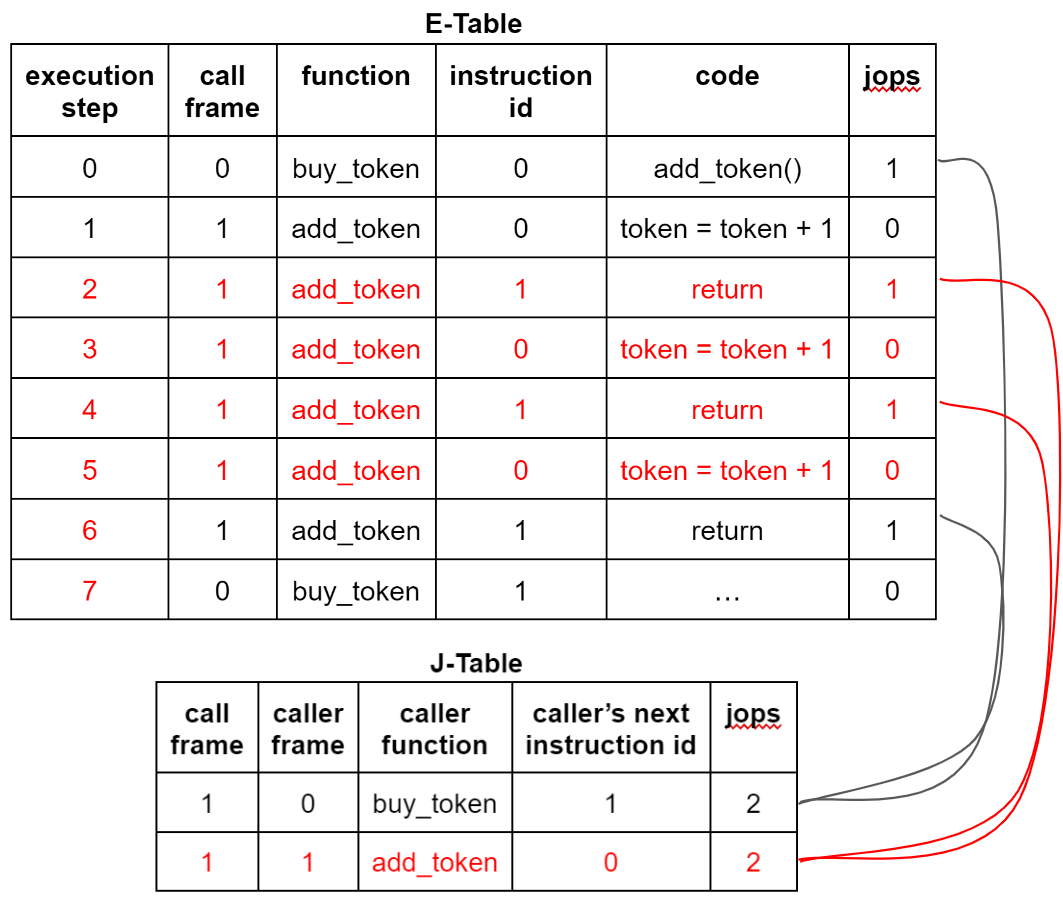

However, two returns are a different story: since no new frame is created upon return, hackers could potentially take a legitimate execution sequence’s execution and call tables and inject forged returns (and corresponding frames). For example, the earlier case of buy_token() calling add_token() in the execution and call tables could be maliciously altered by hackers as follows:

Hackers inject two fake returns between the original call and return in the execution table, and add a new forged frame row in the call table (subsequent execution steps in the execution table must then have their row numbers increased by 4). Since each row in the call table still has a jops count of 2, the constraints are satisfied, and the zkWasm proof checker will accept this forged execution sequence as valid. As shown in the diagram, the token account balance increases three times instead of once. Thus, hackers can obtain three tokens while paying for only one.

There are multiple ways to fix this issue. An obvious solution is to separately track calls and returns and ensure that each frame has exactly one call and one return.

You may have noticed that we haven’t shown a single line of code related to this vulnerability. The main reason is that no individual line of code is incorrect—the code implementation fully aligns with the table and constraint design. The problem lies entirely in the design itself, and so does its fix.

You might think this vulnerability should be obvious, but in reality, it is not. There is a gap between realizing that "two calls or two returns both lead to a jops count of 2" and confirming that "two returns are actually possible." The latter requires detailed, comprehensive analysis of various related constraints in the execution and call tables, making informal reasoning extremely difficult.

Comparison of the Two Vulnerabilities

Both the "Load8 Data Injection Vulnerability" and the "Fake Return Vulnerability" could enable hackers to manipulate ZK proofs, create fraudulent transactions, deceive proof checkers, and steal or hijack assets. However, their natures and methods of discovery are fundamentally different.

The "Load8 Data Injection Vulnerability" was discovered during the zkWasm audit. This was no easy task, as we had to review over 6,000 lines of Rust code and hundreds of constraints across numerous zkWasm instructions. Nevertheless, this vulnerability was relatively easier to identify and confirm. Since this vulnerability was fixed before formal verification began, it did not surface during the verification phase. Had it not been found during the audit, we would expect it to emerge during the formal verification of the Load8 instruction.

The "Fake Return Vulnerability" was discovered during formal verification after the audit. One reason we missed it during the audit is that zkWasm has a mechanism very similar to jops called "mops," which tracks memory access instructions associated with each memory cell’s historical data during zkWasm execution. The mops counting constraint is indeed correct because it tracks only one type of memory instruction—memory writes—and each memory cell’s history is immutable and written only once (mops count = 1). But even if we had noticed this potential vulnerability during the audit, without rigorous formal reasoning across all relevant constraints, we would still struggle to confirm or rule out all possibilities—because, critically, no single line of code is wrong.

In summary, these two vulnerabilities belong respectively to "code vulnerabilities" and "design vulnerabilities." Code vulnerabilities are relatively superficial, easier to detect (due to erroneous code), and easier to reason about and confirm. Design vulnerabilities can be deeply hidden, much harder to detect (with no "wrong" code), and far more challenging to reason about and confirm.

Best Practices for Discovering ZK Vulnerabilities

Based on our experience auditing and formally verifying zkVMs and other ZK and non-ZK chains, here are some recommendations for best protecting ZK systems.

Examine Both Code and Design

As discussed, vulnerabilities can exist in both the code and design of ZK systems. Both types can compromise the system and must be eliminated before deployment. Compared to non-ZK systems, a key issue with ZK systems is that attacks are harder to expose and analyze due to the absence of publicly recorded computational details on-chain. People might know an attack occurred but cannot determine technically how it happened. This makes the cost of any ZK vulnerability extremely high. Consequently, the value of proactively ensuring ZK system security is exceptionally high.

Conduct Both Auditing and Formal Verification

The two vulnerabilities discussed here were discovered via auditing and formal verification, respectively. Some might assume that formal verification eliminates the need for auditing, as all vulnerabilities would be caught during verification. Our recommendation, however, is to perform both. As explained at the beginning of this article, high-quality formal verification begins with thorough review, inspection, and informal reasoning about code and design—activities that overlap significantly with auditing. Additionally, identifying and eliminating simpler vulnerabilities during auditing makes subsequent formal verification simpler and more efficient.

When auditing and formally verifying a ZK system, the optimal approach is to conduct both simultaneously, enabling auditors and formal verification engineers to collaborate efficiently (potentially uncovering more vulnerabilities, as formal verification targets require high-quality audit inputs).

If your ZK project has already undergone auditing (great) or multiple audits (even better), we recommend conducting formal verification of the circuit based on prior audit results. Our repeated experience auditing and formally verifying zkVMs and other ZK and non-ZK projects shows that verification often catches subtle vulnerabilities missed during audits. Due to the nature of ZKPs, while ZK systems should offer superior blockchain security and scalability compared to non-ZK solutions, their own security and correctness are far more critical than in traditional non-ZK systems. Therefore, the value of high-quality formal verification for ZK systems far exceeds that for non-ZK systems.

Ensure Security of Both Circuits and Smart Contracts

ZK applications typically consist of two parts: circuits and smart contracts. For zkVM-based applications, there is a general-purpose zkVM circuit and smart contract applications. For non-zkVM-based applications, there are application-specific ZK circuits and corresponding smart contracts deployed on L1 chains or the other end of a bridge. Based on zkVM vs. non-zkVM

Our audit and formal verification work on zkWasm focused solely on the zkWasm circuit. From the overall security perspective of ZK applications, auditing and formal verification of their smart contracts are equally important. After investing significant effort into securing the circuit, it would be unfortunate if negligence toward smart contract security ultimately compromised the application.

Two types of smart contracts deserve special attention. The first are those directly handling ZK proofs. Although they may not be large in size, their risk level is extremely high. The second are medium-to-large smart contracts running on zkVMs. We know they can sometimes be highly complex, and the most valuable ones should undergo auditing and verification—especially because their execution details are invisible on-chain. Fortunately, after years of development, formal verification of smart contracts is now practical and ready for appropriate high-value targets.

Let us summarize the impact of formal verification (FV) on ZK systems and their components with the following statements:

-

FV Circuit + Non-FV Smart Contract = Non-FV Zero-Knowledge Proof

-

Non-FV Circuit + FV Smart Contract = Non-FV Zero-Knowledge Proof

-

FV Circuit + FV Smart Contract = FV Zero-Knowledge Proof

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News