With aggregation, settlement, and execution layers forming a triad, how do we assess the value of projects within this sector?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

With aggregation, settlement, and execution layers forming a triad, how do we assess the value of projects within this sector?

As competition and technological advancements continue to reduce infrastructure costs, the expense of integrating applications/app-chains with modular components becomes more feasible.

Written by: Bridget Harris

Translation: TechFlow

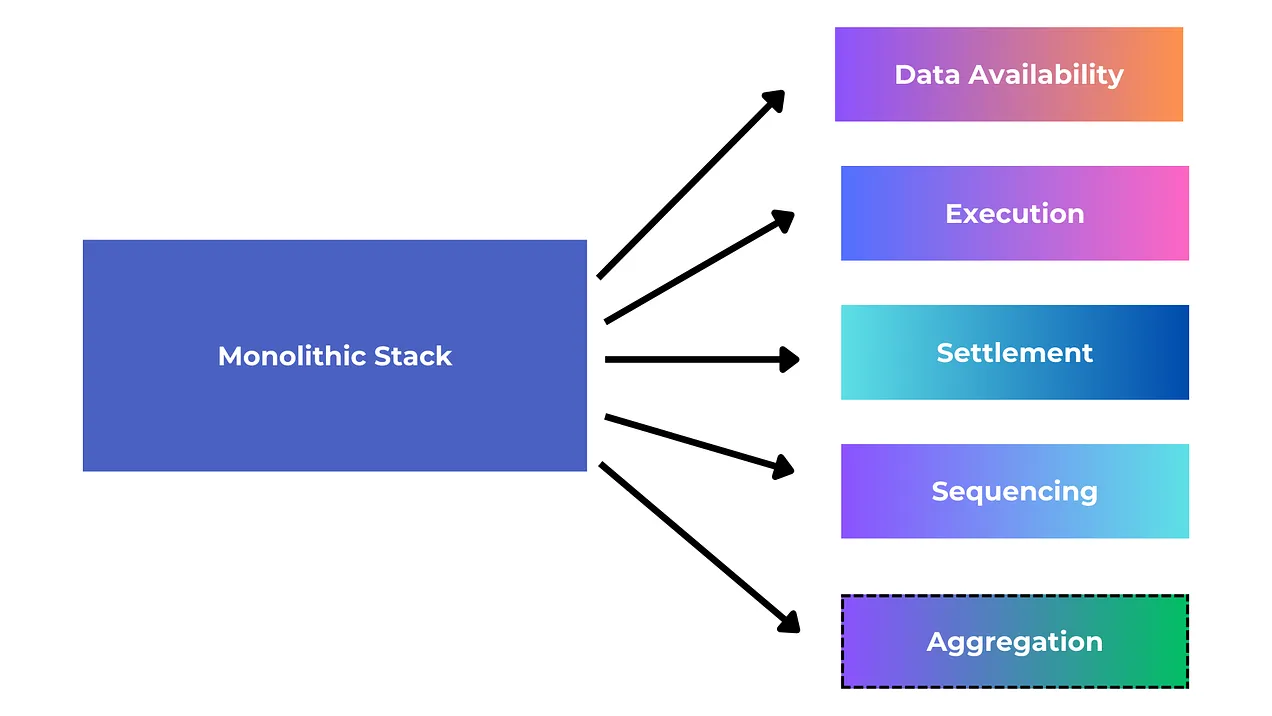

The components of the modular stack are not equally prominent in terms of attention and innovation. While historically many projects have innovated on data availability (DA) and sequencing layers, the execution and settlement layers—critical parts of the modular stack—have been relatively overlooked until recently.

In the shared sequencer market, numerous projects are competing for market share, including Espresso, Astria, Radius, Rome, and Madara. Additionally, Rollup-as-a-Service (RaaS) providers such as Caldera and Conduit are developing shared sequencers for rollups built atop their infrastructure. Since these RaaS providers’ core business models do not fully depend on sequencing revenue, they can offer more favorable fee splits to their rollups. All of these coexist with many rollups that choose to run their own sequencers and gradually decentralize them over time to capture generated fees.

The sequencer market is distinct from the DA space, which is essentially an oligopoly dominated by Celestia, Avail, and EigenDA. This makes it difficult for smaller new entrants outside these three giants to successfully disrupt the market. Projects either leverage “existing” options—Ethereum itself—or opt for established DA layers, depending on the type of tech stack and alignment they seek. While using a dedicated DA layer offers significant cost savings, outsourcing sequencers is not a clear-cut decision (from a fee perspective, not security), primarily due to the opportunity cost of forgoing generated fees. Many also believe DA will become commoditized, but we’ve already seen in crypto that strong liquidity protection combined with unique (hard-to-replicate) underlying technology makes it harder to commoditize any given layer of the stack. Regardless of these debates and shifts, numerous DA and sequencing solutions are now live in production—in short, for certain modular stacks, “every service has multiple competitors.”

Execution and settlement layers (and emerging aggregation layers) have seen relatively little development but are now beginning to iterate in novel ways that better integrate with the rest of the modular stack.

Revisiting the Execution + Settlement Layer Relationship

Execution and settlement layers are tightly coupled. The settlement layer defines the final state outcome of execution and can enhance the execution layer’s results, making it more robust and secure. In practice, this could mean various capabilities—for example, the settlement layer might resolve fraud disputes, validate proofs, or serve as a cross-chain bridge between different execution layers.

It's also worth noting that some teams are building consensus execution environments directly into their protocols. One example is Repyh Labs, which is building Delta, a Layer 1 that takes a design opposite to modular stacks but still offers flexibility within a unified environment and technical compatibility advantages, since teams don’t need to manually integrate each component of a modular stack. Of course, the downsides include fragmented liquidity, lack of choice among optimal modular layers, and high costs.

Other teams choose to build L1s highly specialized around a single core function or application. An example is Hyperliquid, which built an L1 perpetuals trading platform specifically for its flagship native application. Although users must bridge over from Arbitrum, its core architecture doesn’t rely on Cosmos SDK or other frameworks, enabling iterative customization and hyper-optimization tailored to its primary use case.

Progress in the Execution Layer

Its predecessor (still present from the last cycle) was the general-purpose alt-L1, whose only advantage over Ethereum was higher throughput. This meant that historically, projects aiming for major performance gains had to build their own alternative L1 from scratch—mainly because Ethereum itself lacked the necessary technology. Historically, this simply meant embedding efficiency mechanisms directly into general-purpose protocols. In this cycle, however, performance improvements are achieved through modular designs, most of which are implemented on top of the dominant smart contract platform—Ethereum—allowing both existing and new projects to leverage new execution layer infrastructure without sacrificing Ethereum’s liquidity, security, and community moat.

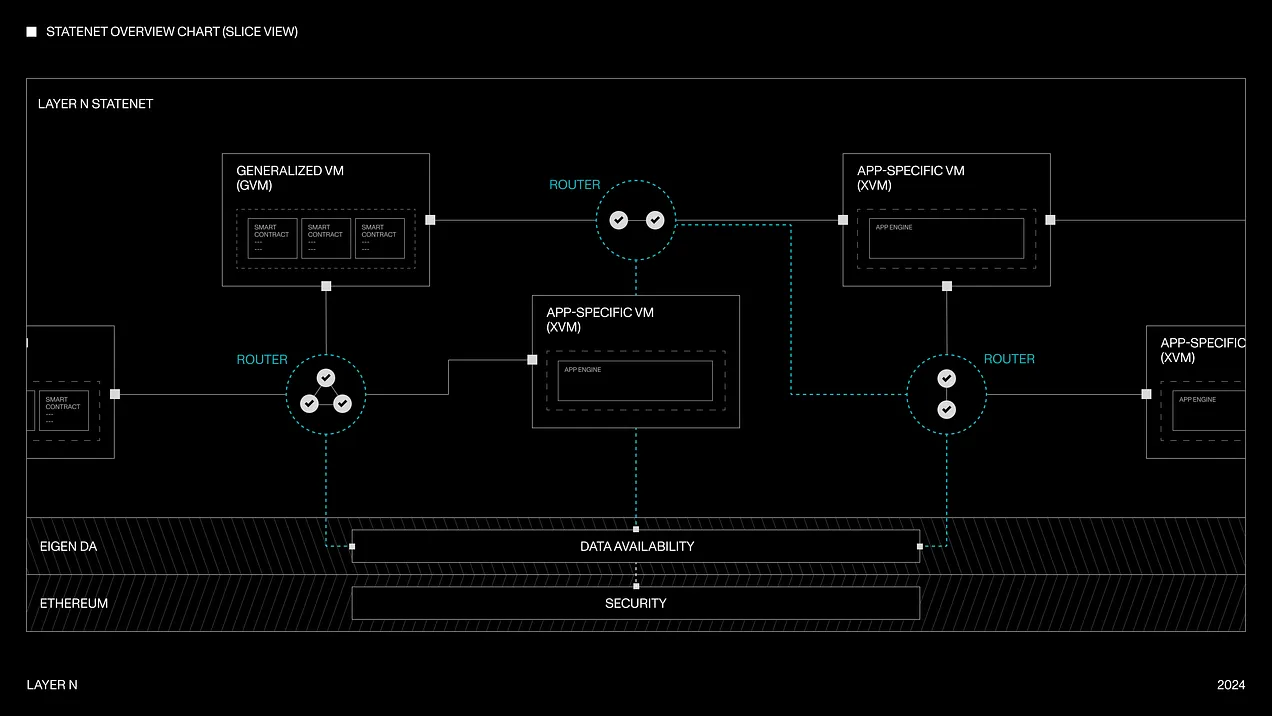

Now, we’re also seeing more hybridization and mixing of different virtual machines (execution environments) as part of shared networks, allowing developers greater flexibility and customization at the execution layer. For example, Layer N enables developers to run general-purpose rollup nodes (e.g., SolanaVM, MoveVM as execution environments) and application-specific rollup nodes (e.g., perps DEX, orderbook DEX) on its shared state machine. They also work toward full composability and shared liquidity across these different VM architectures—a historically challenging on-chain engineering problem at scale. Each application on Layer N can asynchronously pass messages to others without consensus latency, a common pain point in crypto. Each xVM can also use different database architectures, whether RocksDB, LevelDB, or custom synchronous databases built from scratch. Interoperability works via a “snapshot system” (similar to the Chandy-Lamport algorithm), where chains can transition to new blocks asynchronously without pausing the system. On the security side, fraud proofs can be submitted if state transitions are incorrect. With this design, their goal is to minimize execution time while maximizing overall network throughput.

Layer N

To align with these advances in customization, Movement Labs leverages the Move language (originally designed by Facebook for networks like Aptos and Sui) for its VM/execution layer. Compared to other frameworks, Move offers structural advantages in security and developer expressiveness—two historically persistent challenges when building chains today. Importantly, developers can write Solidity and deploy directly on Movement. To achieve this, Movement created an EVM runtime fully bytecode-compatible, usable alongside the Move stack. Their rollup—M2—uses BlockSTM parallelization to achieve higher throughput while still accessing Ethereum’s liquidity moat (historically, BlockSTM was used only by alt-L1s like Aptos, which clearly lack EVM compatibility).

MegaETH is also pushing forward the execution layer frontier, particularly through its parallelization engine and in-memory DB, allowing the sequencer to store the entire state in memory. Architecturally, they utilize:

-

Native code compilation, which delivers higher L2 performance (significant speedups for compute-intensive contracts, and still over 2x acceleration even for non-compute-heavy ones).

-

Relatively centralized block production, but relatively decentralized block validation.

-

Efficient state synchronization, where full nodes don’t need to re-execute transactions but instead understand state deltas to apply them locally.

-

An optimized Merkle tree update structure (which normally requires significant storage). Their approach uses a new triplet data structure with high memory and disk efficiency. During in-memory computation, chain state is compressed into memory, so transaction execution accesses memory—not disk.

As part of the modular stack, proof aggregation is another design recently being explored and iterated upon—it refers to a prover that creates one succinct proof from multiple succinct proofs. First, let’s take a broader look at aggregation layers and their history and current trends in crypto.

Valuing the Aggregation Layer

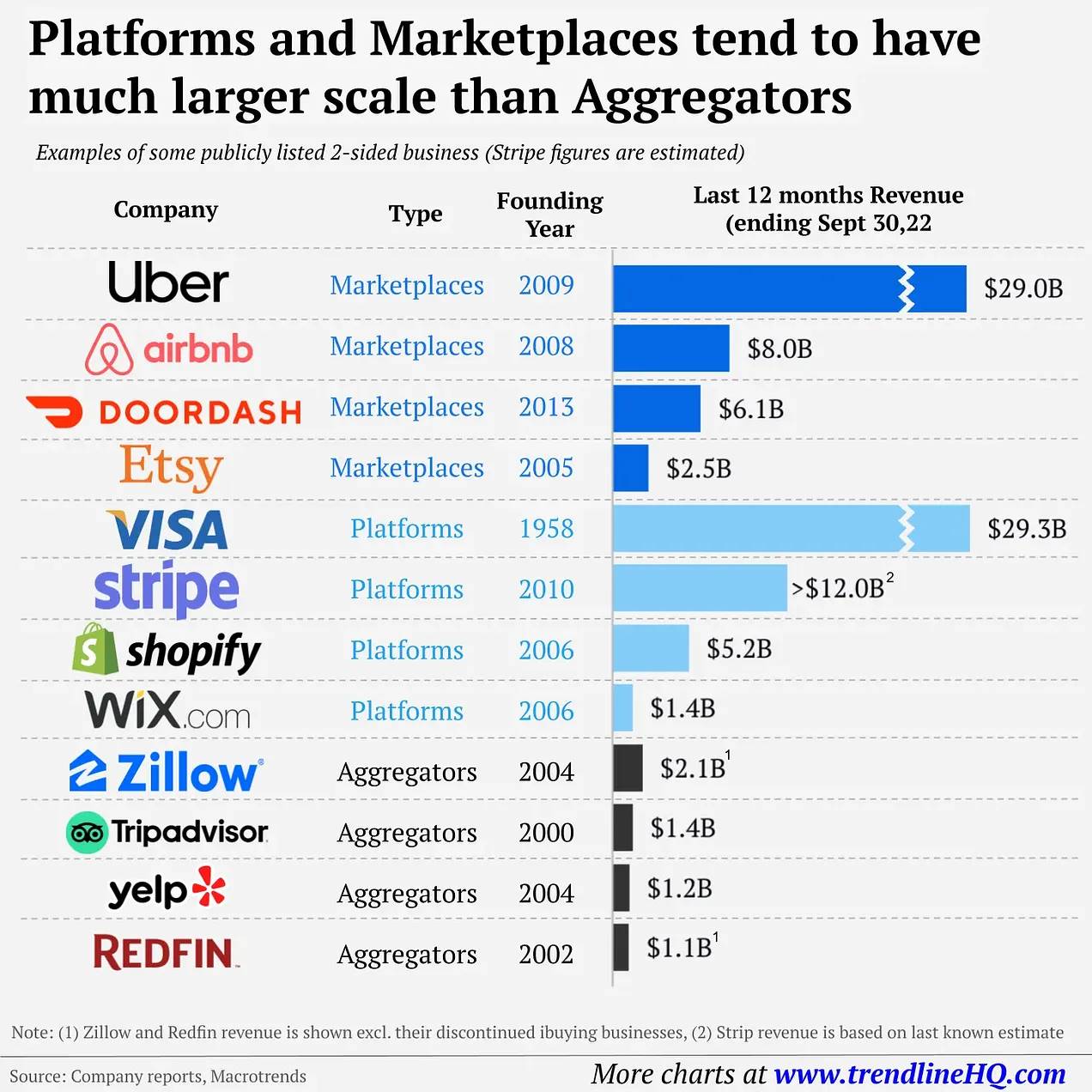

Historically, in non-crypto markets, aggregators have captured less market value than platforms or marketplaces.

CJ Gustafson

While I'm unsure if this holds true in crypto, it certainly applies to decentralized exchanges, cross-chain bridges, and lending protocols. For example, 1inch and 0x (two major DEX aggregators) have a combined market cap of about $1 billion—only a fraction of Uniswap’s ~$7.6 billion. The same applies to cross-chain bridges: compared to platforms like Across, bridge aggregators like Li.Fi and Socket/Bungee appear to have smaller market shares. Although Socket supports 15 different bridging protocols, its total bridged volume is actually similar to Across’s (Socket—$2.2 billion, Across—$1.7 billion), while Across accounts for only a small fraction of Socket/Bungee’s recent transaction volume.

In lending, Yearn Finance was the first decentralized yield aggregator protocol, with a current market cap of around $2.5 million. In contrast, platform products like Aave (~$1.4 billion) and Compound (~$5.6 million) have achieved higher valuations and relevance over time.

Traditional financial markets operate similarly. For example, U.S.-based ICE (Intercontinental Exchange) and CME Group each have market caps of about $7.5 billion, while “aggregators” like Charles Schwab and Robinhood have market caps of ~$132 billion and ~$15 billion, respectively. Inside Schwab, trades are routed through many venues including ICE and CME, yet their trading volume is disproportionate to their market cap share. Robinhood handles approximately 119 million options contracts monthly, while ICE handles about 35 million, despite options not being central to Robinhood’s business model. Yet, ICE is valued about five times higher than Robinhood in public markets. Thus, Schwab and Robinhood—acting as application-level aggregation interfaces routing customer order flow across various venues—are valued lower than ICE and CME despite their large volumes.

As consumers, we simply assign less value to aggregators.

This may not hold in crypto if the aggregation layer is embedded directly into the product/platform/chain. If aggregators are tightly integrated into the chain, it’s clearly a different architecture—and one I’m eager to see evolve. For example, Polygon’s AggLayer allows developers to easily connect their L1s and L2s into a network that aggregates proofs and enables a unified liquidity layer across chains using CDK.

AggLayer

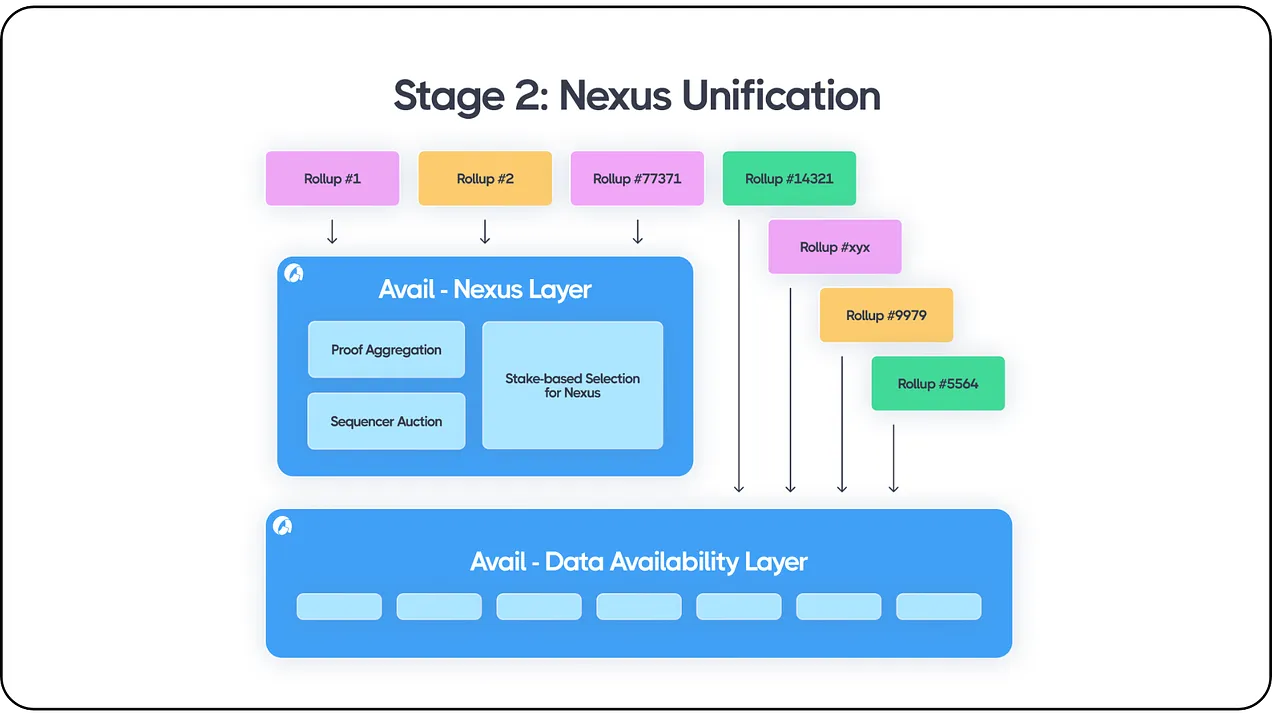

This model works similarly to Avail’s Nexus interoperability layer, which includes proof aggregation and a sequencer auction mechanism to strengthen their DA offering. Like Polygon’s AggLayer, every chain or rollup integrated with Avail becomes interoperable within Avail’s existing ecosystem. Moreover, Avail aggregates ordered transaction data from diverse blockchain platforms and rollups—including Ethereum, all Ethereum rollups, Cosmos chains, Avail rollups, Celestia rollups, and hybrid structures like Validiums, Optimiums, and Polkadot parachains. Developers from any ecosystem can permissionlessly build atop Avail’s DA layer while using Avail Nexus for cross-ecosystem proof aggregation and messaging.

Avail Nexus

Nebra focuses specifically on proof aggregation and settlement, capable of aggregating across different proof systems—e.g., aggregating proofs from system xyz and system abc into agg_xyzabc (rather than aggregating only within a single proof system). The architecture uses UniPlonK, which standardizes verifier work across circuit families, making it more efficient and feasible to verify proofs from different PlonK circuits. At its core, it leverages zero-knowledge proofs themselves (recursive SNARKs) to scale verification work—the typical bottleneck in such systems. For clients, the final settlement step becomes easier, as Nebra handles all batch aggregation and settlement; teams only need to modify API contract calls.

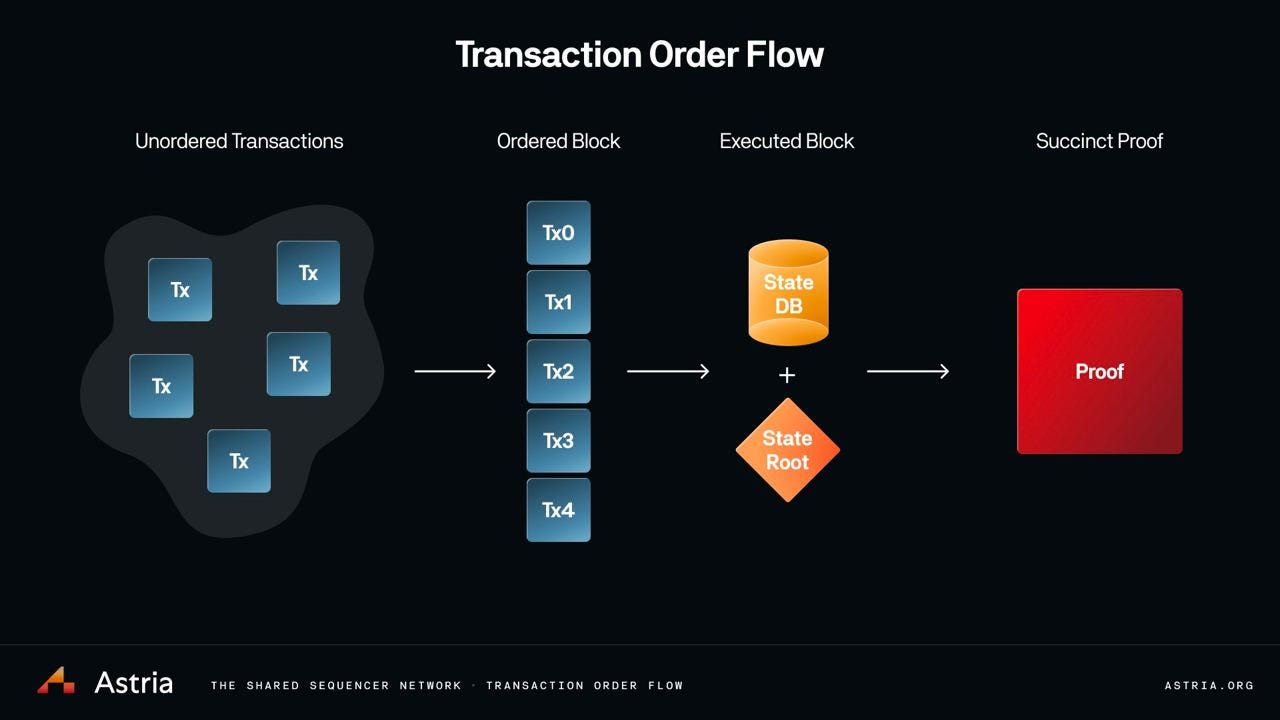

Astria is designing interesting integrations around how their shared sequencer works with proof aggregation. They leave execution entirely to the rollups themselves, which run execution layer software on a given namespace of the shared sequencer—essentially just an “execution API,” a way for rollups to ingest sequenced data. They can also easily add support here for validity proofs to ensure blocks don’t violate EVM state machine rules.

Josh Bowen

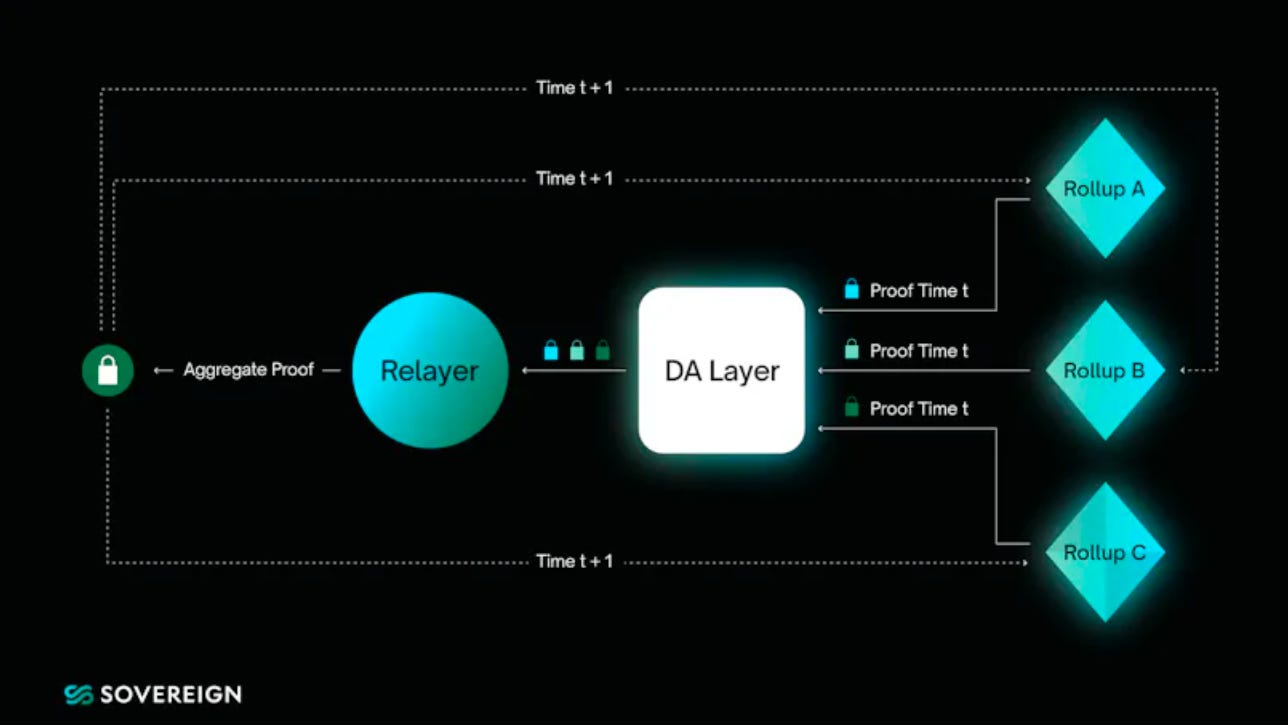

Here, products like Astria handle the #1→#2 process (unordered transactions → ordered blocks), execution layer/rollup nodes handle #2→#3, and protocols like Nebra serve as the final step #3→#4 (executed blocks → succinct proofs). Nebra (or Aligned Layer) could even represent a theoretical fifth step, where proofs are further aggregated and then verified. Sovereign Labs is also exploring a similar concept for the final step, where proof-aggregation-based bridges are central to their architecture.

Sovereign Labs

Overall, some application-layer projects are beginning to own underlying infrastructure, partly because maintaining only a high-level application may create incentive misalignments and high user adoption costs if they don’t control the base stack. On the other hand, as competition and technological progress continue to reduce infrastructure costs, the expense of applications/application chains integrating with modular components becomes increasingly feasible. I believe this momentum is far stronger—at least for now.

With all these innovations—across execution, settlement, and aggregation layers—higher efficiency, easier integration, stronger interoperability, and lower costs are becoming more achievable. Ultimately, this translates to better applications for users and a superior developer experience for builders. It’s a winning combination that fosters greater and faster innovation—I’m excited to see what comes next.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News