Blast Chain's $97 Million Battle: Have Hackers From a Certain Country Gotten Rusty?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Blast Chain's $97 Million Battle: Have Hackers From a Certain Country Gotten Rusty?

What Happened to the Munchables Project Attack, Exposing Approximately $97 Million in Risk?

Author: CertiK

Background

Blast is an Ethereum Layer 2 network launched by Pacman (Tieshun Roquerre, aka. Tie Shun), the founder of Blur. It went live on February 29 and currently has approximately 19,500 ETH and 640,000 stETH staked on the Blast mainnet.

The attacked project, Munchables, was a top-performing project in Blast's Bigbang competition.

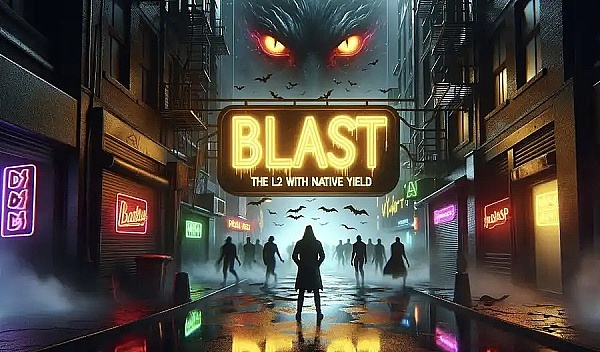

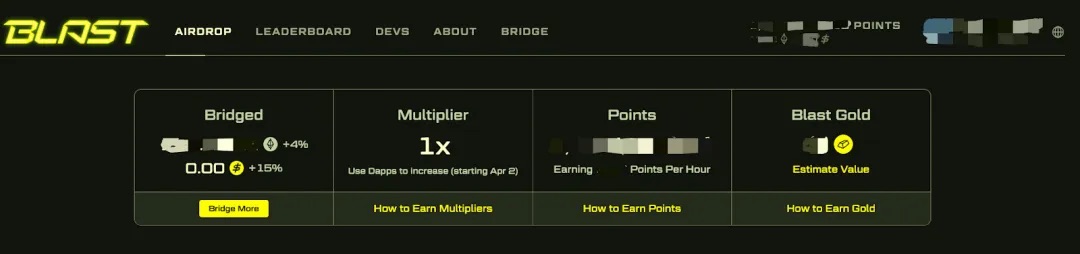

Blast officially rewards users who stake ETH on its mainnet with standard points:

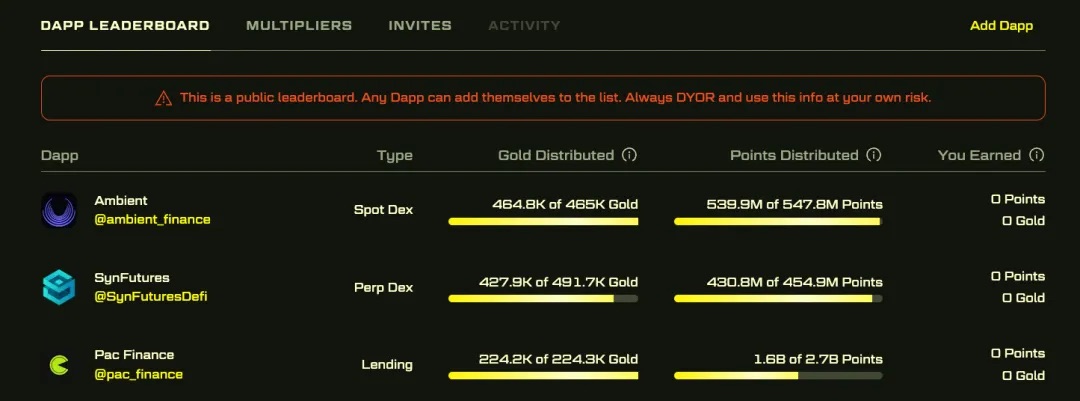

To encourage user participation in DeFi projects within the Blast ecosystem, Blast selects high-quality projects for recommendation and incentivizes users to re-stake their ETH into DeFi protocols, which accelerates point accumulation and grants access to gold points. As a result, many users have re-staked their ETH from the Blast mainnet into newly created DeFi projects.

However, the maturity and security of these DeFi projects remain questionable—can these contracts truly safeguard tens of millions or even hundreds of millions of dollars belonging to users?

Incident Overview

Less than a month after Blast’s mainnet launch, on March 21, 2024, an attack targeted SSS Token (Super Sushi Samurai). A logic flaw in the token contract allowed attackers to mint arbitrary amounts of SSS tokens to designated accounts, resulting in a loss exceeding 1,310 ETH (approximately $4.6 million).

Then, less than a week after the SSS token incident, another major attack occurred on Blast: the Munchables project was drained of 17,413.96 ETH, totaling around $62.5 million.

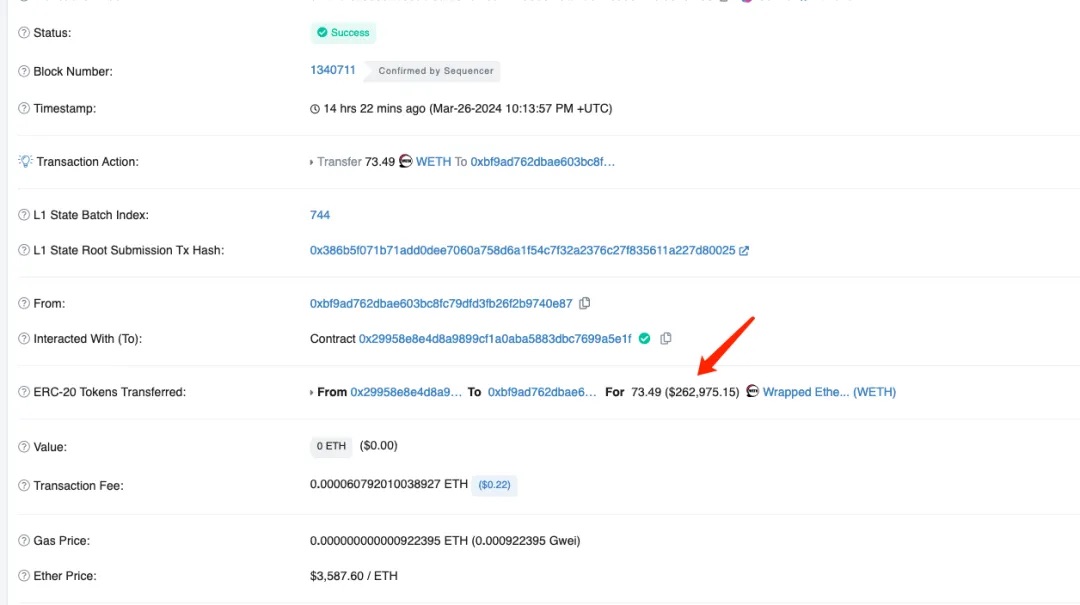

Half an hour after this attack transaction, 73.49 WETH from the project’s contract were also stolen to another address controlled by the hacker.

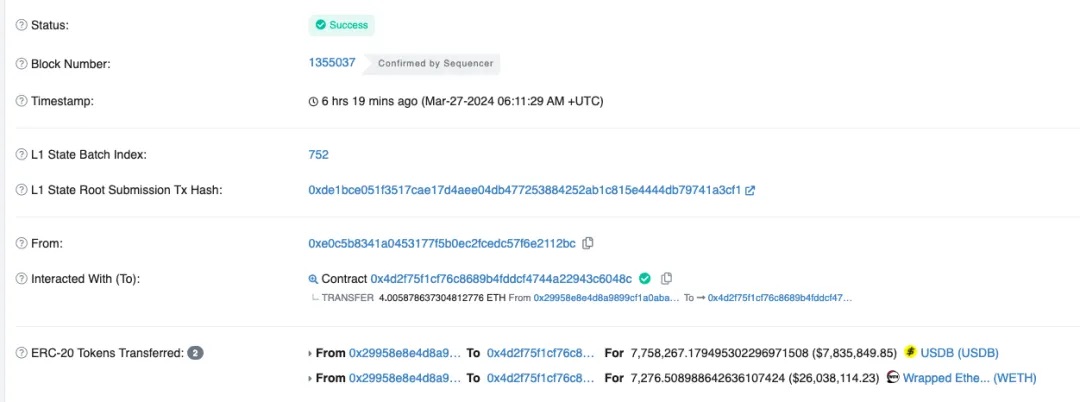

At that moment, the project’s contract still held 7,276 WETH, 7,758,267 USDB, and 4 ETH—all at immediate risk of being fully drained. The attacker had complete control over all remaining funds, exposing approximately $97 million to imminent danger.

Shortly after the incident, renowned on-chain investigator zachXBT pointed out on X (Twitter) that the root cause stemmed from hiring a hacker from a certain country.

Let us dive deeper into how this “certain-country hacker” executed an attack nearing $100 million.

Scene Reconstruction

Victim Response

[UTC+0] On March 26, 2024, at 21:37 (five minutes after the attack), Munchables officially announced the breach on X (Twitter).

According to investigator ZachXBT’s findings, one of their developers was the said "hacker from a certain country." Coderdan, founder of Aavegotchi, also confirmed on X (Twitter): "Pixelcraft Studios, the development team behind Aavegotchi, briefly hired the Munchables attacker in 2022 for some game development work. His technical skills were rough—he genuinely seemed like someone from that country. We fired him within a month. He even tried to get us to hire his friend, who likely was also such a hacker."

Given the massive losses suffered by the community, we immediately initiated an on-chain investigation. Let’s now examine the details of this “certain-country hacker” attack.

First Scene

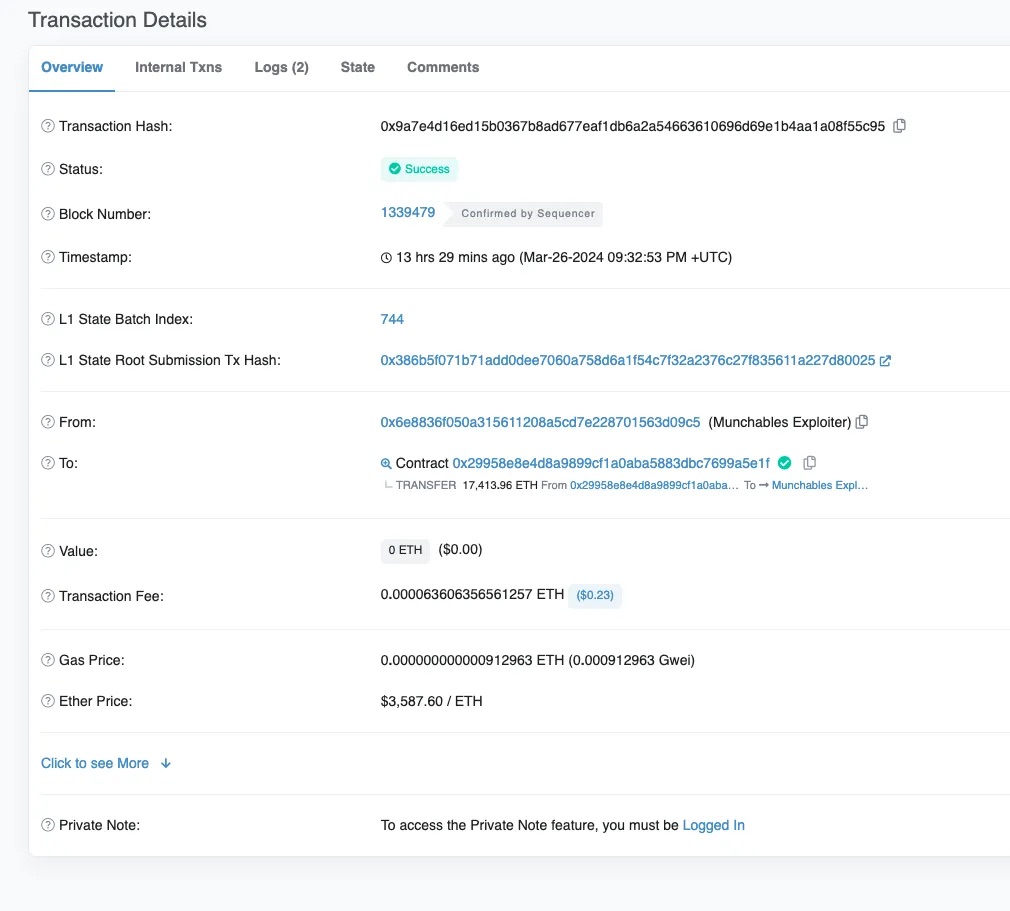

[UTC+0] On March 26, 2024, at 21:32, the attack involving 17,413.96 ETH occurred.

Using Blastscan, we can view the attack transaction: https://blastscan.io/tx/0x9a7e4d16ed15b0367b8ad677eaf1db6a2a54663610696d69e1b4aa1a08f55c95

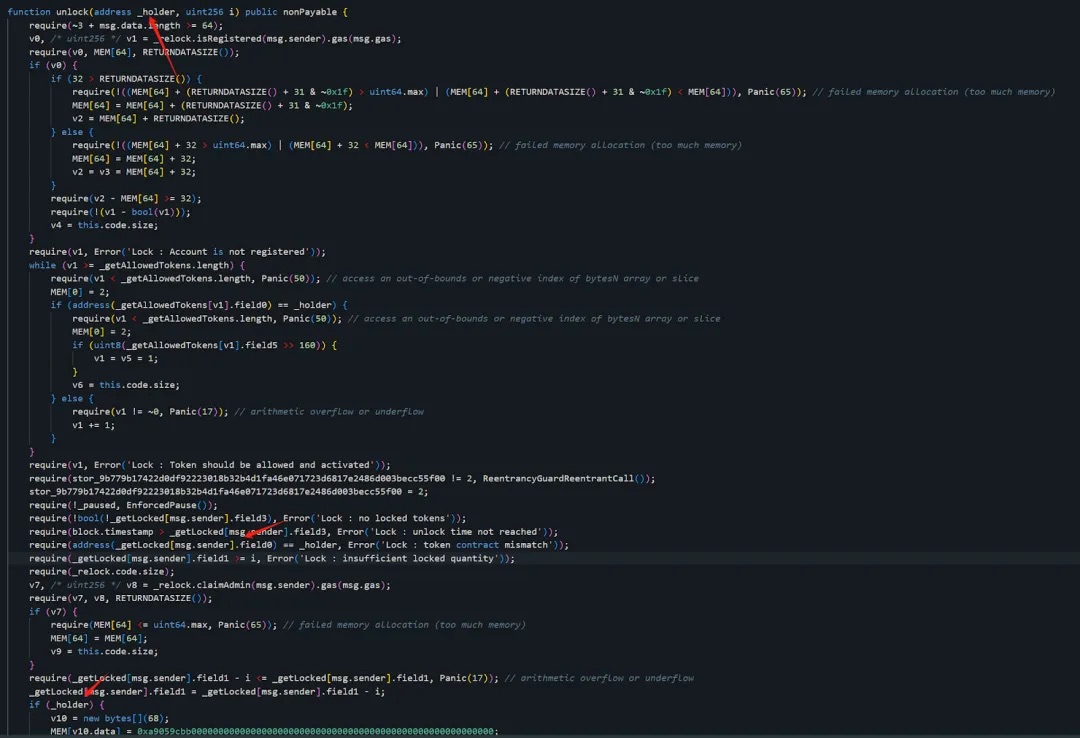

The compromised contract (0x29...1F) is a proxy contract holding users’ staked funds. We observe that the attacker called the unlock function of the staking contract, passed all authorization checks, and transferred all ETH from the contract to attacker address 1 (0x6E...c5).

It appears the attacker invoked an unlock function similar to withdraw, draining most of the ETH from the affected contract (0x29...1F).

Did the project forget to lock its treasury?

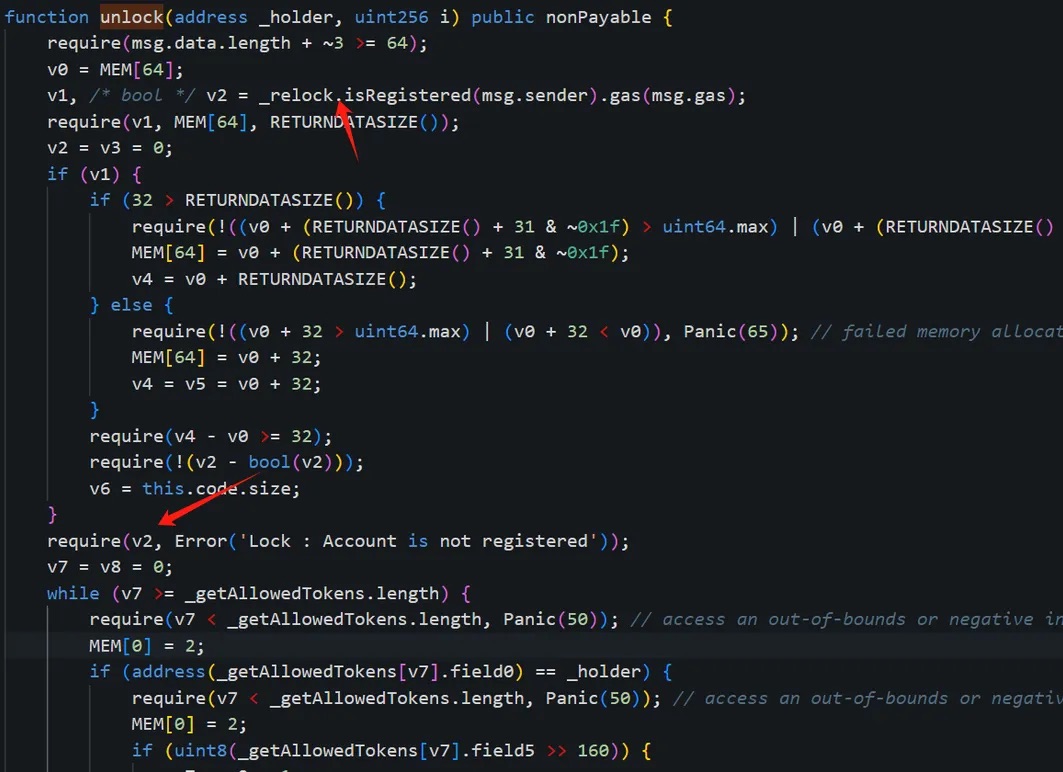

The unlock function in the compromised contract (0x29...1F) involves two key validations—we’ll analyze them one by one.

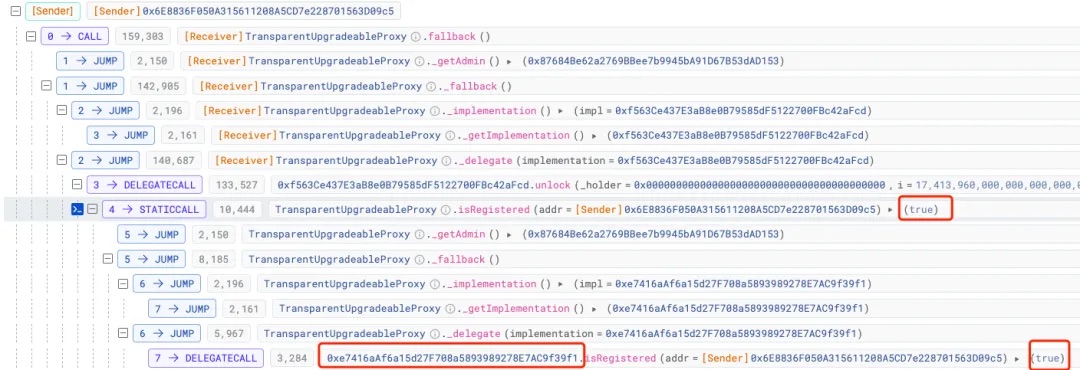

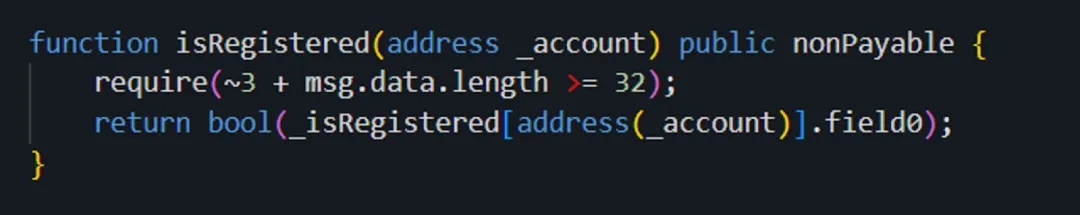

First, during the permission check process, the contract calls the isRegistered method of contract (0x16...A0) to verify whether the current msg.sender—attacker address 1 (0x6E...c5)—has been registered:

Result: The verification passed.

This involves contract (0x16...A0) and its latest logic contract (0xe7...f1).

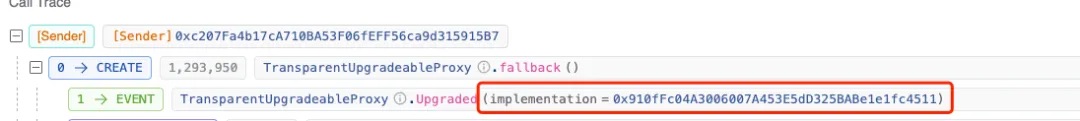

[UTC+0] On March 24, 2024, at 08:39 (two days before the attack), the logic contract associated with (0x16...A0) was upgraded.

Logic contract upgrade transaction:

https://blastscan.io/tx/0x9c431e09a80d2942319853ccfdaae24c5de23cedfcef0022815fdae42a7e2ab6

The logic contract was updated to 0xe7...f1.

The original logic contract address was 0x9e...CD, visible here:

https://blastscan.io/tx/0x7ad050d84c89833aa1398fb8e5d179ddfae6d48e8ce964f6d5b71484cc06d003

We initially suspected that the hacker had replaced the proxy contract’s implementation with a malicious version (from 0x9e...CD to 0xe7...f1), thereby bypassing authorization checks.

Was that really what happened?

In Web3, you never need to guess or rely solely on others—you just need technical knowledge to find your own answers.

By comparing the two contracts (both not open-sourced), we found clear differences between the original 0x9e...CD and the updated 0xe7...f1:

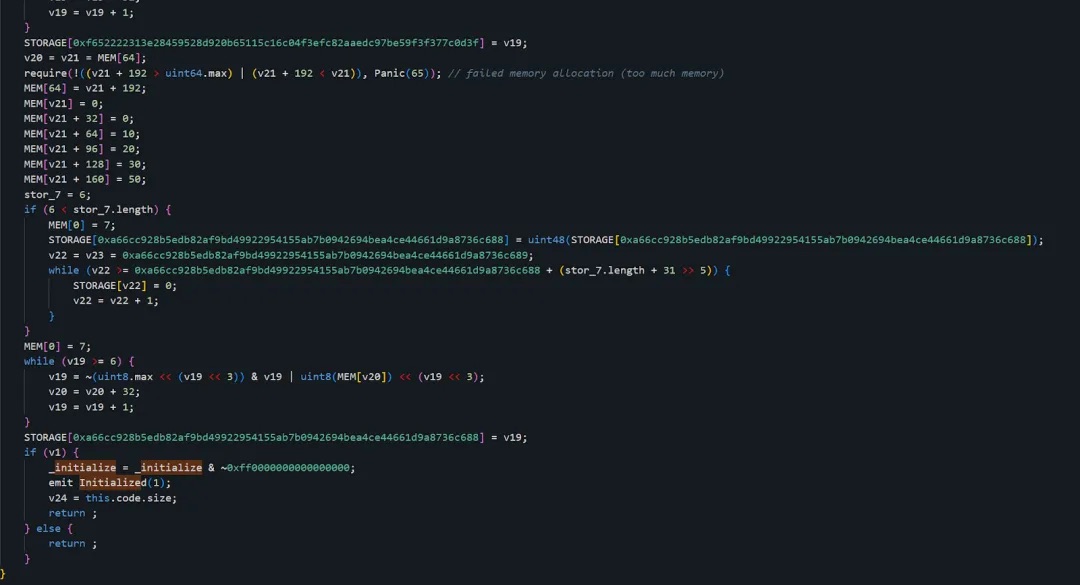

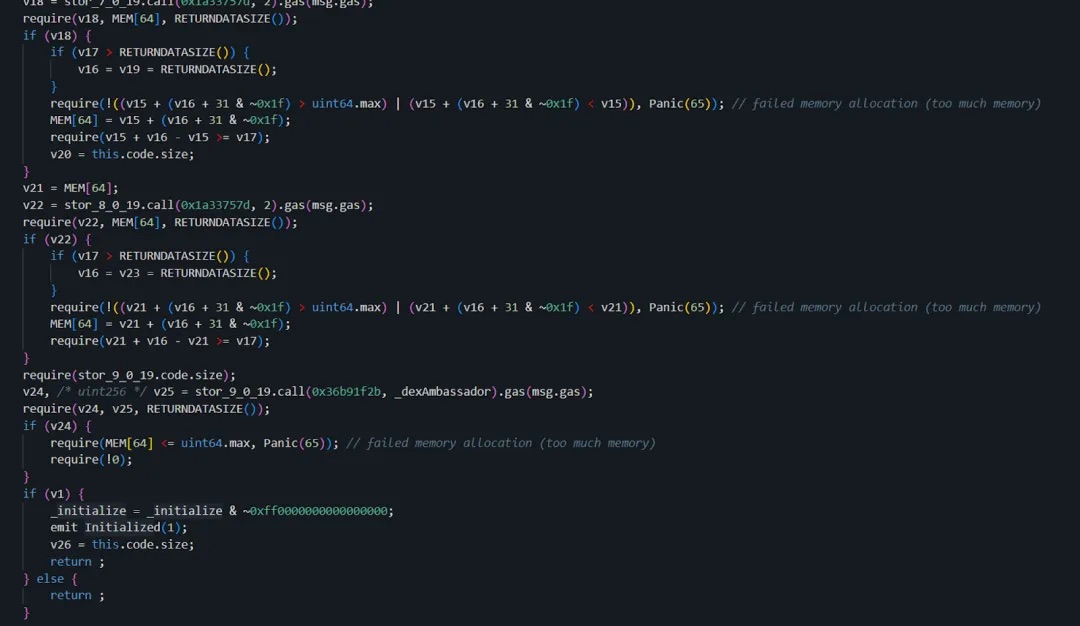

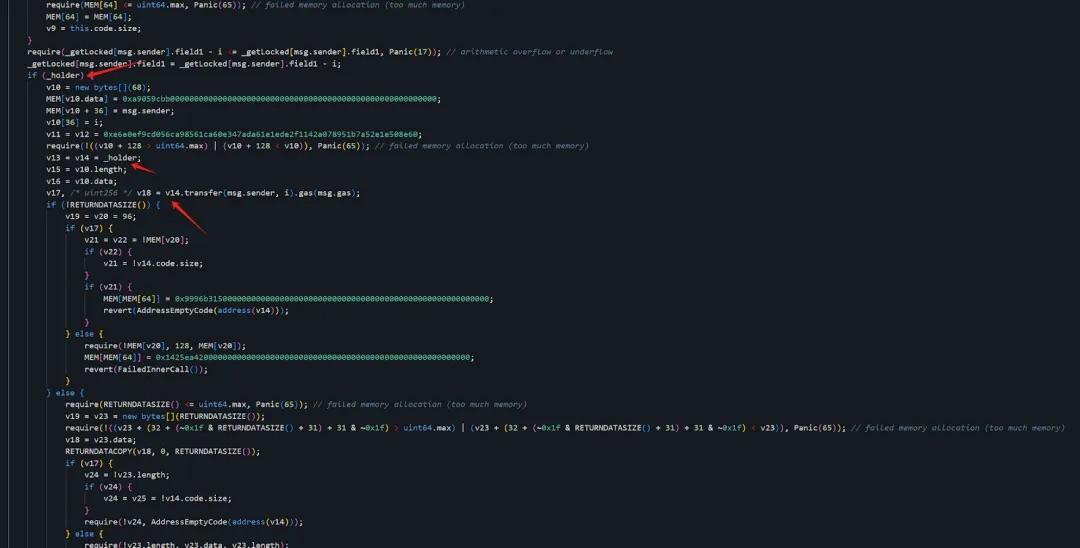

The initialize function in 0xe7...f1 is implemented as follows:

The initialize function in 0x9e...CD is implemented as follows:

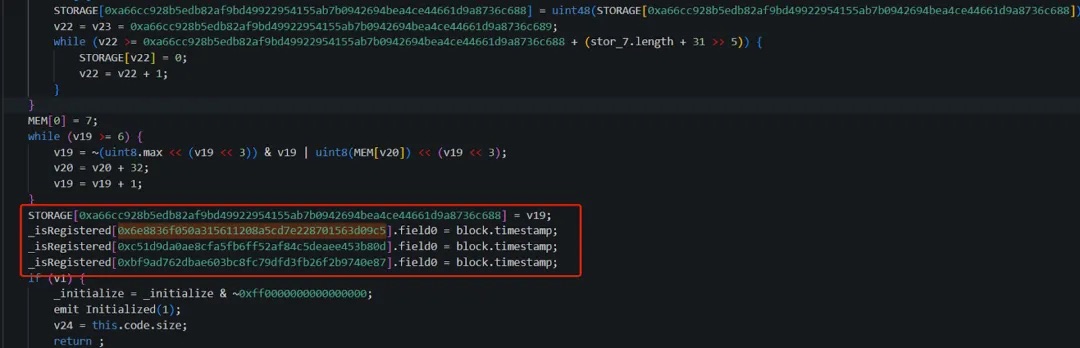

As seen, in the original logic contract (0x9e...CD), the attacker pre-registered their own address (0x6e...c5) along with two other attacker addresses: 0xc5...0d and 0xbf...87. Their field0 values were set to the block timestamp at initialization—a value we will explain later.

Contrary to our initial assumption, the truly backdoored logic contract was actually the original one—the later update contained a clean, legitimate contract!

Wait—the upgrade occurred on [UTC+0] March 24, 2024, at 08:39 (two days before the attack), meaning the logic contract had already been replaced with a non-malicious version prior to the incident. Then why could the attacker still succeed?

This is due to delegatecall behavior: state storage changes are applied directly to the proxy contract (0x16...A0). Therefore, even after upgrading to the clean logic contract 0xe7...f1, the altered storage slots in (0x16...A0) remained unchanged.

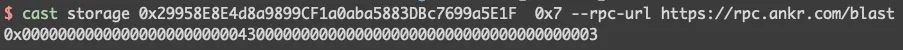

Let’s verify this:

Indeed, the corresponding slot in contract (0x16...A0) contains data.

This allowed the attacker to pass the isRegistered check:

The attacker first deployed the backdoored contract, then replaced it with a clean one to conceal their tracks—by the time investigators examined the code, everything appeared normal. Since none of the contracts were open-sourced, identifying the core issue became even harder.

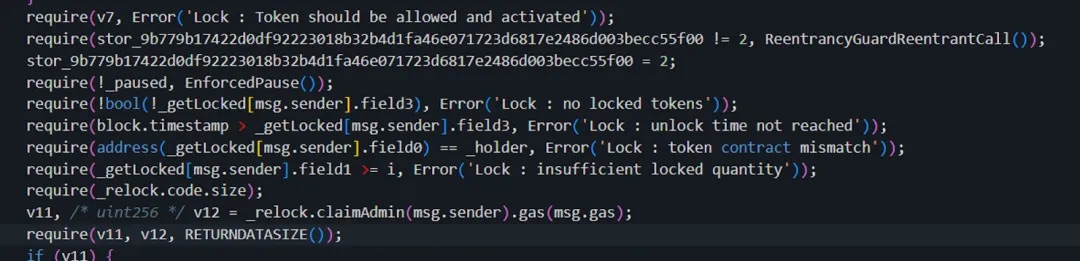

Additionally, the unlock process includes a second validation:

A check on the lock duration, ensuring locked assets cannot be withdrawn before maturity.

The attacker needed to ensure that when unlock was called, the current block timestamp exceeded the required expiration time (field3).

This part involves the compromised contract (0x29...1F) and its corresponding logic contract 0xf5...cd.

On [UTC+0] March 21, 2024, at 11:54 (five days before the attack),

https://blastscan.io/tx/0x3d08f2fcfe51cf5758f4e9ba057c51543b0ff386ba53e0b4f267850871b88170

We see that the original logic contract for the compromised contract (0x29...1F) was 0x91...11. Just four minutes later,

https://blastscan.io/tx/0xea1d9c0d8de4280b538b6fe6dbc3636602075184651dfeb837cb03f8a19ffc4f

it was upgraded to 0xf5...cd.

Comparing both contracts reveals the attacker used the same technique—tampering with the initialize function.

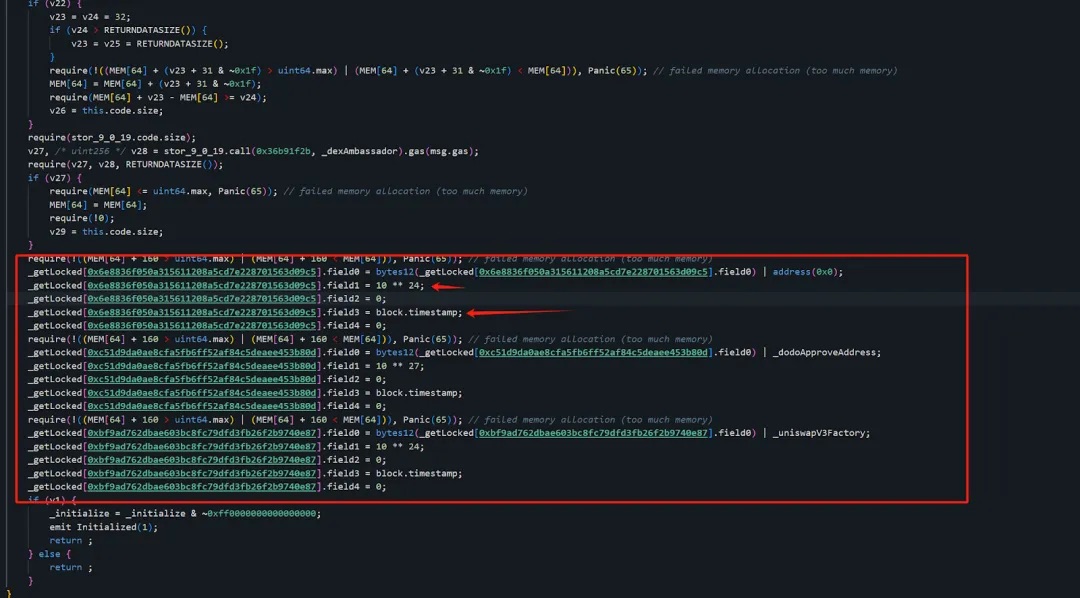

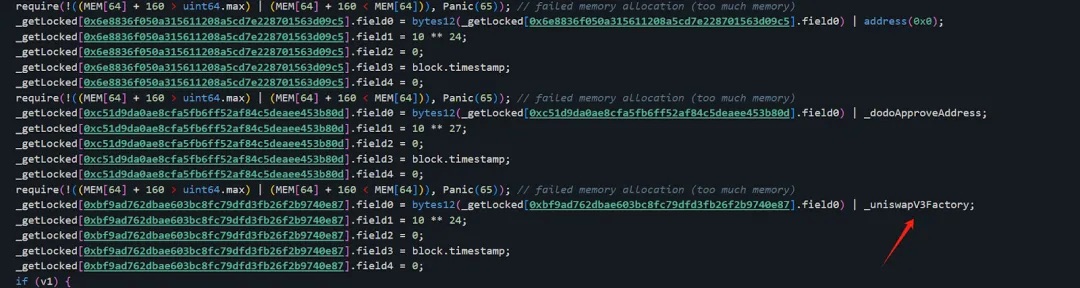

Initialize function in 0xf5...cd:

Initialize function in 0x91...11:

Clearly, the attacker again used identical methods—altering their own ETH balance and unlock timing—then replacing the contract with a clean version to mislead auditors. When the team and security researchers debugged the system, they saw only legitimate logic contracts. With no source code available, uncovering the real issue became extremely difficult.

Now we understand how the 17,413 ETH transaction was executed—but does this story go deeper?

From our earlier analysis, we observed that the hacker embedded three addresses inside the contract:

0x6e...c5 (Attacker Address 1)

0xc5...0d (Attacker Address 2)

0xbf...87 (Attacker Address 3)

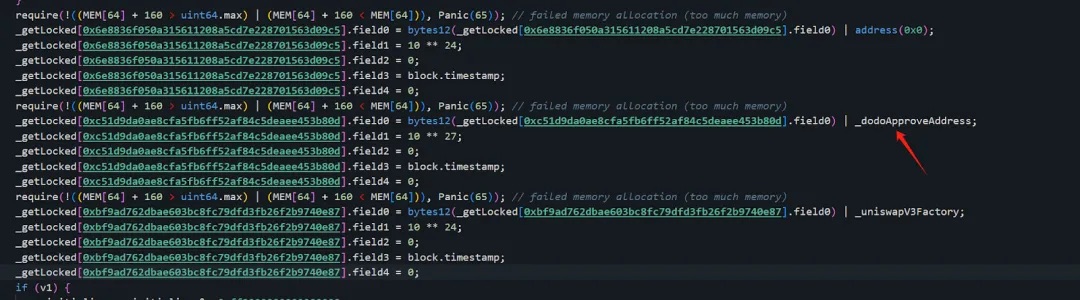

But so far, we’ve only seen activity from 0x6e...c5. What did the other two do? And what secrets lie behind address(0), _dodoApproveAddress, and _uniswapV3Factory?

Second Scene

Let’s examine attacker address 3 (0xbf...87), which similarly stole 73.49 WETH:

https://blastscan.io/tx/0xfc7bfbc38662b659bf6af032bf20ef224de0ef20a4fd8418db87f78f9370f233

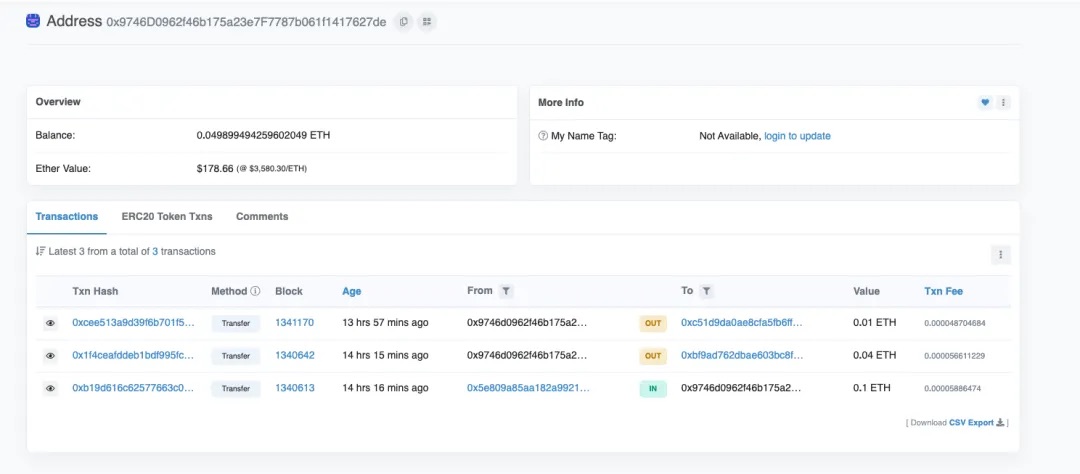

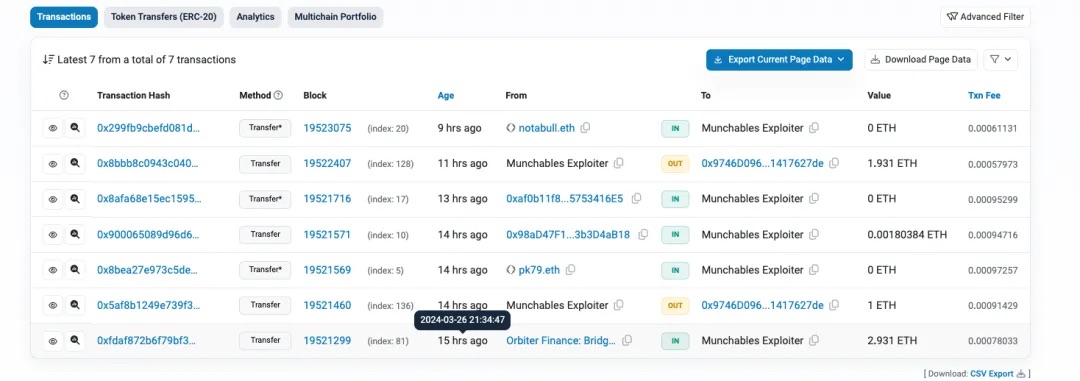

The gas funding address (0x97...de) simultaneously paid gas fees for both 0xc5...0d (Attacker Address 2) and 0xbf...87 (Attacker Address 3).

The 0.1 ETH used by the gas source address (0x97...de) originated from owlto.finance (a cross-chain bridge).

After receiving gas funds, 0xc5...0d (Attacker Address 2) did not perform any attacks but instead played a hidden role—let’s continue investigating.

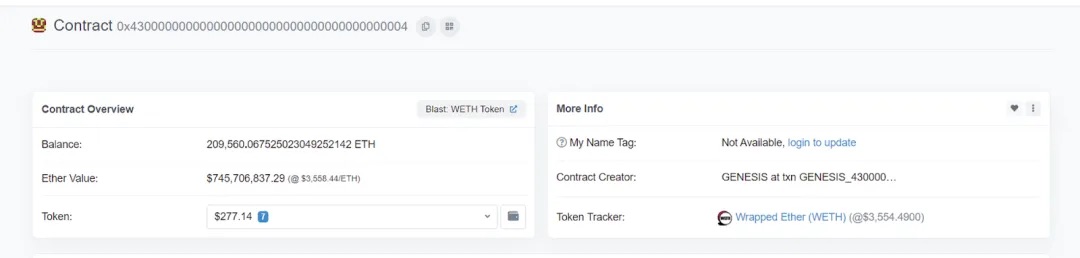

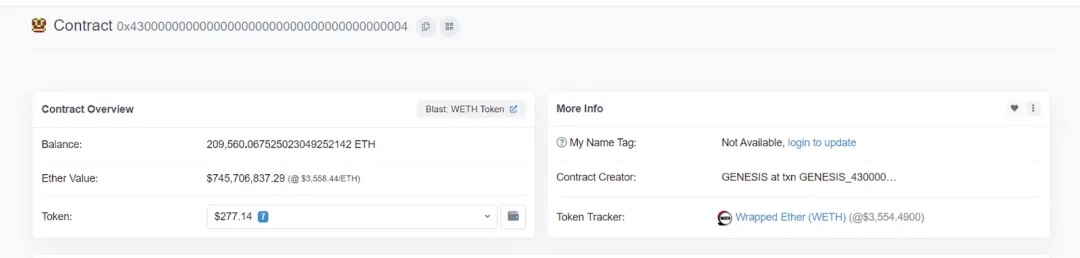

In fact, according to the official rescue transaction, the compromised contract (0x29...1F) originally held more than just 73.49 WETH—until the end of the attack, it still retained 7,276.5 WETH and 7,758,267 USDB.

Rescue transaction:

https://blastscan.io/tx/0x1969f10af9d0d8f80ee3e3c88d358a6f668a7bf4da6e598e5be7a3407dc6d5bb

The attacker initially intended to steal all these assets. In fact, 0xc5...0d (Attacker Address 2) was meant to steal the USDB.

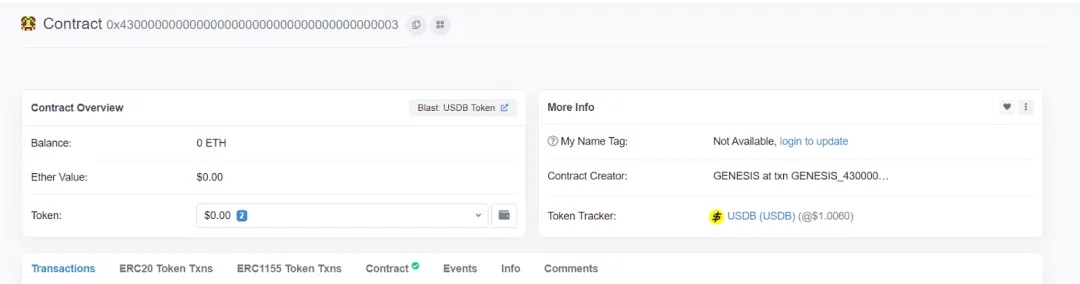

Here, _dodoApproveAddress equals 0x0000000000000000000000004300000000000000000000000000000000000003

which corresponds to the USDB address

Similarly, 0xbf...87 (Attacker Address 3) was designed to steal WETH:

Here, _uniswapV3Factory equals 0x0000000000000000000000004300000000000000000000000000000000000004

which corresponds to the WETH address

Meanwhile, 0x6e...c5 (Attacker Address 1) was responsible for stealing address(0)—the native asset ETH.

By setting field0 appropriately, the attacker could exploit the following logic to steal each respective asset:

Questions

Why didn’t the attacker steal all the assets?

Theoretically, he could have taken all remaining assets—WETH and USDB alike.

0xbf...87 (Attacker Address 3) only took 73.49 WETH, though it could have easily drained all 7,350 WETH. Similarly, using 0xc5...0d (Attacker Address 2), it could have taken all 7,758,267 USDB. Why stop after taking just a small amount of WETH? We don’t know—the answer may require deeper internal investigation by renowned on-chain detectives.

https://blastscan.io/tx/0xfc7bfbc38662b659bf6af032bf20ef224de0ef20a4fd8418db87f78f9370f233

Why didn’t the attacker transfer the 17,413 ETH to Ethereum mainnet immediately?

It is well known that Blast’s mainnet could potentially intercept these ETH via centralized mechanisms, keeping them frozen and preventing actual user losses. However, once ETH enters the Ethereum mainnet, interception becomes impossible.

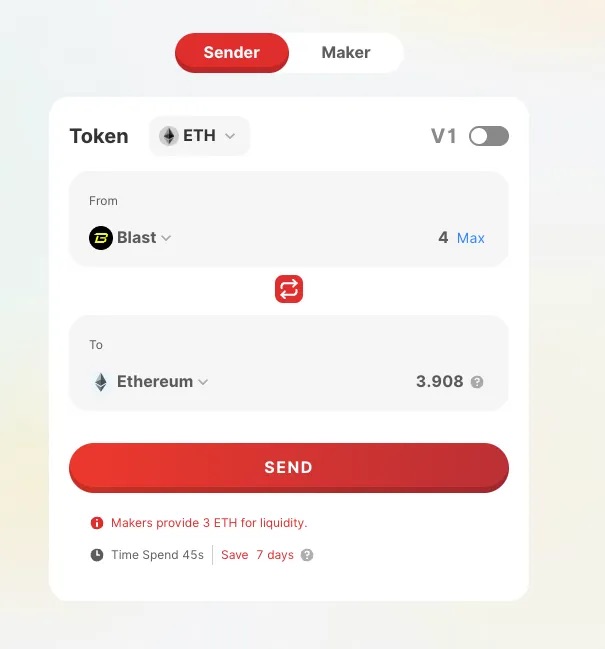

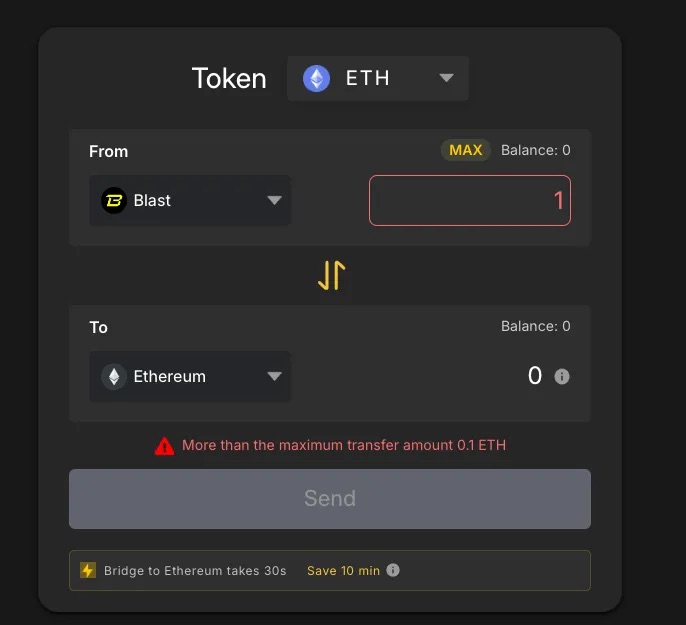

We assessed Blast’s current bridges: the official bridge imposes no amount limits but requires a 14-day withdrawal period—ample time for Blast to prepare an interception plan.

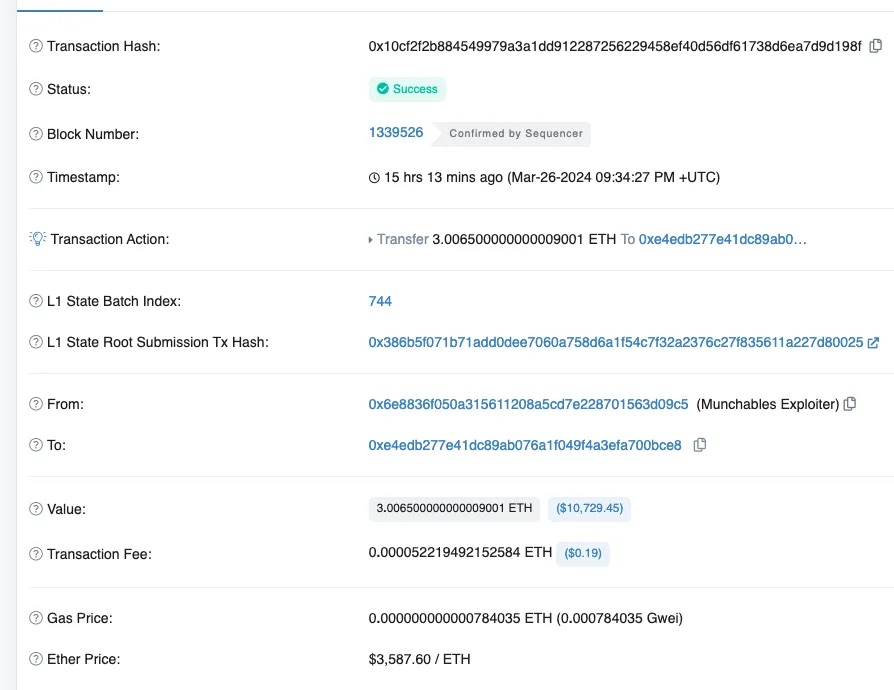

Third-party bridges offer near-instant settlement, just like the attacker’s gas funding source, enabling fast cross-chain transfers. So why didn’t the attacker immediately bridge out?

In reality, the attacker *did* initiate a cross-chain transfer within the first two minutes of the attack:

https://blastscan.io/tx/0x10cf2f2b884549979a3a1dd912287256229458ef40d56df61738d6ea7d9d198f

The funds arrived on Ethereum mainnet in just 20 seconds. Theoretically, the attacker could have continued bridging repeatedly, moving large sums before human intervention.

The reason only 3 ETH were moved per transaction lies in bridge liquidity constraints from Blast to ETH:

Another Blast-supported bridge offers even lower capacity:

After this single bridging transaction, the attacker performed no further withdrawals. The reason remains unknown—it appears the “certain-country hacker” may not have adequately prepared for fund exfiltration from Blast.

Post-Attack Developments

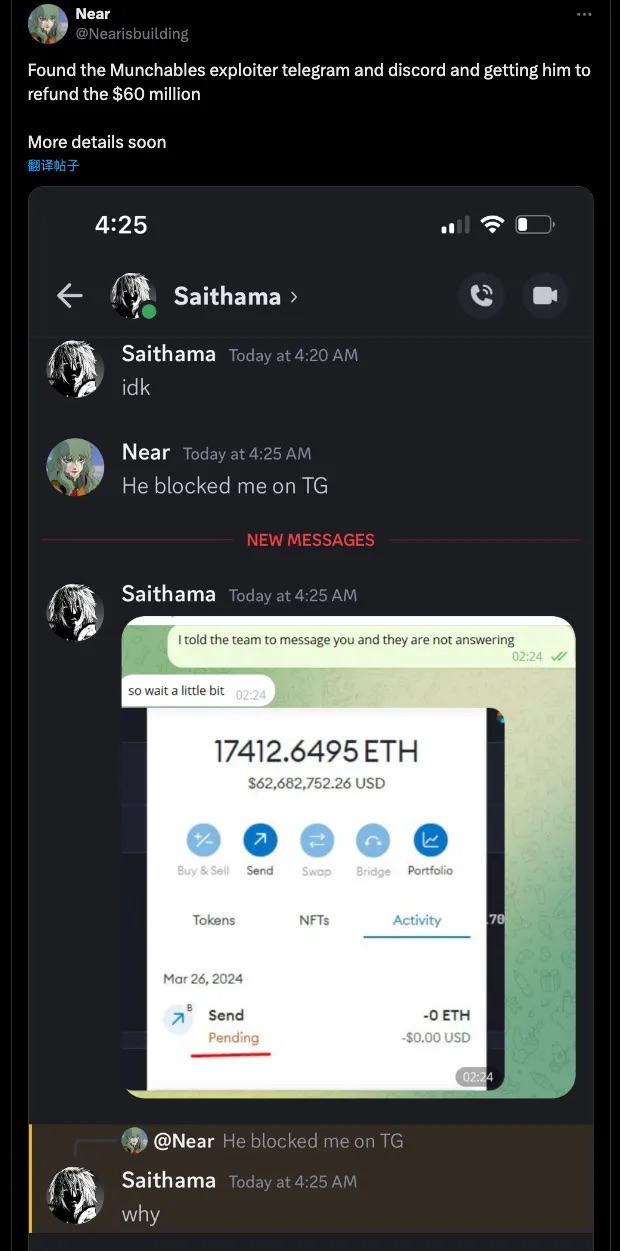

According to feedback from community member Nearisbuilding, he uncovered additional identity clues about the attacker and attempted to pressure them into returning the funds.

https://twitter.com/Nearisbuilding/status/1772812190673756548

Ultimately, under scrutiny and pressure from the crypto community, the “certain-country hacker,” possibly fearing exposure, provided the private keys for the three attacker addresses and returned all funds. The project team executed a rescue transaction, transferring all remaining assets from the compromised contract to a multi-signature wallet for secure custody.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News