The Next Step for Robots

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Next Step for Robots

The ChatGPT Moment for Robots?

By Henry

Are robot advancements moving faster lately?

Recently, research progress in intelligent robots has been heating up, with new demonstrations emerging one after another.

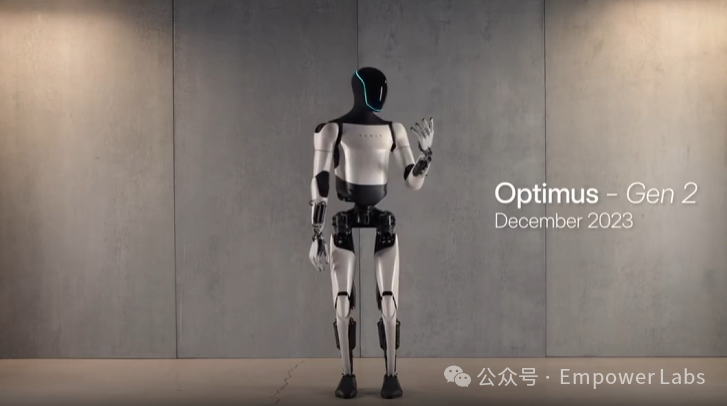

In mid-December, Tesla unveiled its second-generation Optimus. This robot is not a commercial product but a pure prototype—yet it's highly refined. In the demo, this astronaut-shaped Optimus displayed sophisticated motor skills. Musk explained that designing it to be human-sized and shaped was intentional: to seamlessly replace human labor and perform any task people are unwilling to do.

Tesla’s robot exudes a strong sci-fi industrial aesthetic and looks expensive—perhaps precisely why it sets an expectation of “everything being natural.” In reality, however, Tesla hasn’t shown many practical applications for it, so public reaction has mostly been a muted “oh.” But then came two robot announcements in January that prompted genuine “huh?” reactions from many.

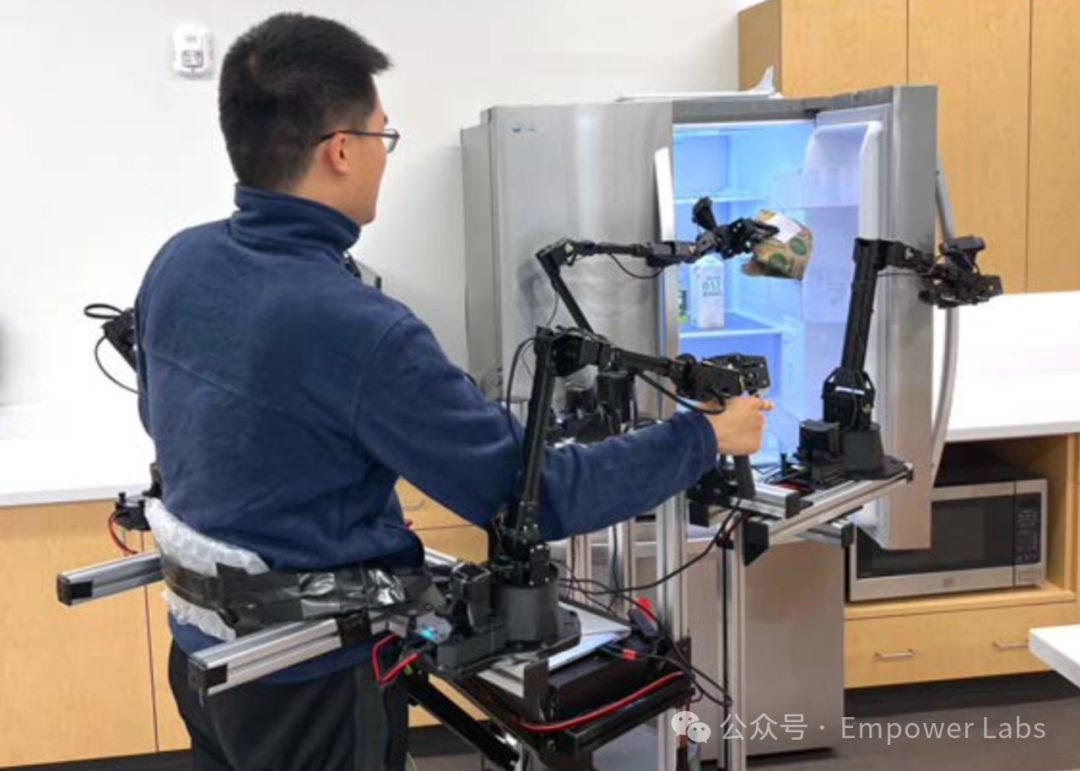

First was the Mobile Aloha project released by a research team from Stanford University. This project attracted widespread interest likely because of its practical use cases: cooking, playing with cats, and doing laundry. The key innovation here is using relatively low-cost hardware (around $30,000—still very expensive for home use) to build an autonomous, mobile, dual-arm manipulation robot (though not particularly humanoid in appearance) capable of learning human skills. The learning process seems slightly quirky: for example, to teach it cooking, you first manually operate it through the steps once, and it roughly remembers the motions. It won’t hold the pan steadily at first, but the magic happens when it uses cameras on its arms to conduct dozens of autonomous training sessions until it truly masters stability.

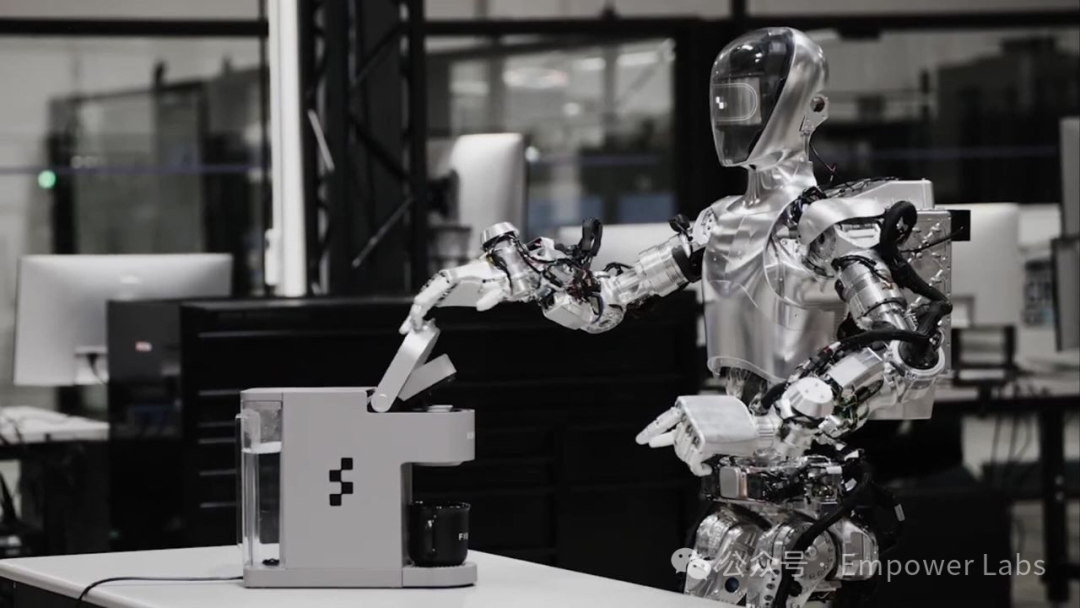

Shortly afterward, Figure released a video showing their humanoid robot, Figure 01, making coffee. Upon hearing the spoken instruction “Make me a cup of coffee,” the robot skillfully operated a capsule coffee machine to brew a cup. Figure dubbed this achievement the “ChatGPT moment for humanoid robots”—not because it used large language models to understand speech, but because this coffee-making skill was learned purely through observing and imitating human actions. The level of awe this feat inspires is comparable to ChatGPT. By visually observing how humans operate the coffee machine, Figure 01 built an understanding of the task, then refined its performance through several rounds of self-training and error correction. This showcases the vast potential of AI-driven general-purpose humanoid robots.

Bill Gates’ “A robot in every home”

Back in the January 2007 issue of *Scientific American*, Bill Gates wrote an article—I remember it was even the cover story. Its title? “A robot in every home.”

In the article, Gates expressed great excitement about opportunities in robotics, comparing it to the early days of Microsoft 30 years prior: breakthrough technologies had emerged, yet professional-grade commercial machines were still monopolized by a few big companies. While startups and hobbyists kept creating interesting things, efforts remained fragmented, lacking universal standards or development tools. Thus, Gates boldly predicted: once these issues are solved, robots would inevitably enter every household.

So Microsoft decisively invested in this vision, establishing a Robotics division and launching Microsoft Robotics Studio, aiming to replicate its PC-era success.

In his article, Gates referenced the classic DARPA 2004 Grand Challenge—the same legendary DARPA that invented the internet. The goal was to have fully autonomous vehicles navigate over 140 miles across the Mojave Desert. In the first year, the best-performing vehicle managed only seven grueling miles. The next year, five vehicles completed the race—and did so at full speed. This competition powerfully illustrated the rapid evolution of robotic technology. And that was exactly where Gates placed his confidence.

Microsoft focused on the development tooling side. Hardware capabilities—sensors, motors, servos—were rapidly improving and prices falling. But on the software side, developers had to write custom drivers for each piece of hardware. Also, getting then-weak processors to handle real-time data from multiple sensors was a major challenge. Microsoft’s solution was twofold: standardizing driver interfaces and providing robust multithreading support. They even introduced the .NET Micro Framework. For those familiar with .NET, putting such a powerful tool into robotics development was like bringing a tank to a bicycle race. Robot developers no longer needed to worry about memory or thread scheduling—they could just focus on writing application logic.

But as we now know, Microsoft’s efforts in robotics ultimately failed. The entire Robotics division was dissolved during a 2014 reorganization. From my own sporadic observations, the main reasons seem to boil down to cost and application. Even today, building a robotic arm at home remains costly, and we still aren’t quite sure what to do with it.

The robot’s ChatGPT moment?

Fast-forward to today. Whether it’s Mobile Aloha or Figure 01, both demonstrate a similar capability: learning an action via sensors (be it cameras or remote joint operations), then mastering it through autonomous feedback training. Moreover, this learned behavior becomes a reusable skill that can be invoked through natural conversation. Such skills can be instantly copied across identical robots—no programming required.

It does appear that robot capabilities have reached a new threshold. This has led many to wonder aloud: “Has robotics reached its own ChatGPT moment?”

Compared to when Gates made his prediction over a decade ago, robots today have made several significant leaps forward:

1. Greater generality. To Gates, robots could take any form as long as they performed tasks. Back when I occasionally attended meetings with Microsoft’s Robotics group, their demos were mostly about basic mobility—rolling or crawling. Today’s robots, however, are acquiring household-relevant skills that are transferable. Additionally, robot designs are increasingly humanoid, aiming to replace humans in performing diverse general tasks.

2. Natural interaction. Empowered by multimodal large language models (LLMs), today’s robots can understand voice commands and learn from visual inputs—a huge leap in machine learning that drastically reduces development and usage barriers.

3. Lower costs. While Mobile Aloha’s published hardware cost exceeds $30,000, that includes a mobile base. If considering just the robotic arm, it’s approaching the price range of high-end home appliances. The mobile base itself may become one of the next hot areas—for instance, some recent investment theses around Tesla argue: “Don’t think of it as an electric car; think of it as the next-generation universal mobile platform.”

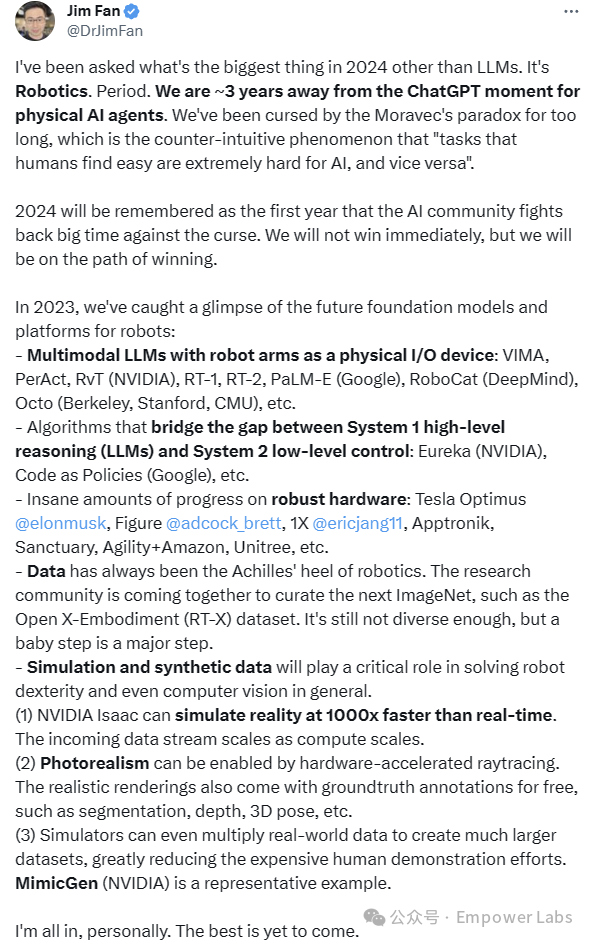

Jim Fan is one of the biggest influencers in this space—an NVIDIA senior scientist and formerly OpenAI’s first intern. In a recent tweet, he laid out why he believes robotics will be the biggest trend of 2024.

Yet even in this enthusiastic post, Jim estimates that “general physical AI robots” are still about three years away.

On this point, I remain cautiously optimistic—optimistic about the sheer scale of progress, cautious due to Microsoft’s earlier missteps.

But one thing is certain: it’s genuinely exciting.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News