A Ten-Thousand-Word Assessment of Bitcoin's Health: Imperfect, but Good Enough

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

A Ten-Thousand-Word Assessment of Bitcoin's Health: Imperfect, but Good Enough

Final grade: A-.

Written by: Lyn Alden

Translated by: Luffy, Foresight News

When investing in Bitcoin as an asset or in companies building on the Bitcoin network, we need metrics to assess the progress of investment themes and thus evaluate the health of the Bitcoin network.

Bitcoin is more than just a price chart; it's an open-source network with millions of users, thousands of developers, hundreds of companies, and multiple ecosystems built upon it. Most Wall Street analysts and retail investors have actually never used a Bitcoin wallet, self-custodied the asset, sent it to others, or used it across various ecosystems—but doing so is highly beneficial for fundamental research.

Bitcoin means different things to different people. It enables portable savings, censorship-resistant global payments, and immutable data storage. If you're an investor in high-quality U.S. or European stocks and bonds and haven't considered Bitcoin from the perspective of middle-class savers in Nigeria, Vietnam, Argentina, Lebanon, Russia, or Turkey, then you haven't fundamentally analyzed this asset’s use cases.

Most importantly, people assess the network's health in many different ways. If Bitcoin doesn’t meet their desired outcome, they may conclude that Bitcoin is underperforming. On the other hand, if Bitcoin fully aligns with what they want, they might believe Bitcoin is performing well even though there are still frictions to resolve.

In recent years, I've spent considerable time studying monetary history and working within the Bitcoin-focused startup/venture capital space, researching the technical details of this protocol. As a result, when assessing the health of the Bitcoin network, I consider several unique key metrics. This article will walk through each one and examine how the Bitcoin network performs on each.

-

Market Capitalization and Liquidity

-

Fungibility and Convertibility

-

Technical Security and Decentralization

-

User Experience

-

Legal Acceptance and Global Recognition

Market Capitalization and Liquidity

Some say price doesn’t matter. They often claim, "1 BTC = 1 BTC." It's not Bitcoin that fluctuates—it's the world around Bitcoin that moves.

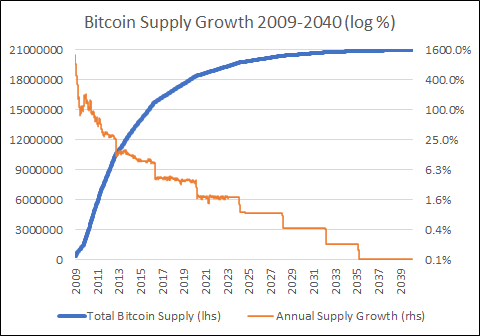

There’s some truth to this. Bitcoin has a maximum supply of 21 million coins, created and distributed in a pre-programmed, decreasing manner. The Bitcoin network generates a block approximately every ten minutes via an automatic difficulty adjustment mechanism and has operated with remarkable consistency since inception—its uptime exceeds that of Fedwire. I don’t know how much the dollar supply will be next year, but I do know exactly how many bitcoins exist, and I can audit the precise supply at any time.

But price is an important signal. It may not mean much day-to-day, week-to-week, or even year-to-year, but over multi-year timeframes, it does carry significance. The Bitcoin network itself may be the heartbeat of clockwork-like order amid a chaotic world, but price remains a measure of its adoption. Bitcoin now competes globally in currency markets against over 160 different fiat currencies, gold, silver, and various other cryptocurrencies. As a store of value, it also competes with non-monetary assets like stocks and real estate—or anything else we can own with limited resources.

It’s not accurate to say, as some supporters suggest, that only the dollar price fluctuates relative to Bitcoin. Compared to the dollar, Bitcoin is a younger, less stable, less liquid, and smaller network, making it significantly more volatile than the dollar. In certain years, Bitcoin holders can buy more property, food, gold, copper, oil, S&P 500 shares, dollars, rupees, or anything else than they could the previous year. In other years, they can afford far less. Bitcoin’s price primarily fluctuates over any given medium-term horizon, and those fluctuations affect holders’ purchasing power. Currently, Bitcoin’s price has risen sharply, meaning Bitcoin holders can buy more than they could a few years ago.

If Bitcoin’s price stagnates long-term, we should ask why Bitcoin fails to attract people. Isn’t it supposed to solve their problems? If not, why?

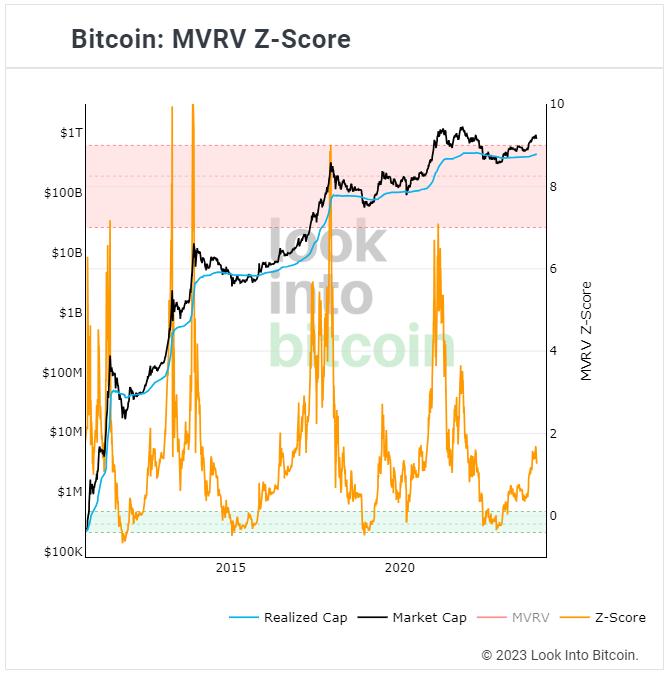

Fortunately, as shown above, that hasn’t been the case. Bitcoin’s price continues to make new highs cycle after cycle. It’s among the best-performing assets in history. I’d argue it has held up remarkably well considering the significant tightening of central bank balance sheets and sharp rise in real interest rates over the past few years. Based on on-chain metrics, historical correlation with global broad money supply, and other factors, Bitcoin appears to continue along its long-term path of adoption and growth.

Then there’s liquidity. What’s the daily trading volume on exchanges? How much transaction value is being sent on-chain? Money is the most liquid good, and liquidity matters greatly.

Bitcoin ranks very well on this metric too, with billions or even tens of billions of dollars traded daily against other currencies and assets. Its daily trading liquidity rivals that of Apple (AAPL) stock. Unlike Apple, where nearly all trading occurs on Nasdaq, Bitcoin trades across numerous exchanges worldwide—including peer-to-peer markets. Daily on-chain transfers on the Bitcoin network also reach into the billions of dollars.

One way to think about liquidity is that liquidity breeds more liquidity. For money, this is a crucial part of the network effect.

When Bitcoin’s daily trading volume was only in the thousands of dollars, someone couldn’t deploy a million dollars without drastically moving the price—they’d have to spread their trade over weeks. To them, it wasn’t yet a sufficiently liquid market.

When Bitcoin’s daily volume reached millions of dollars, one still couldn’t deploy a billion dollars—even spreading trades over weeks wouldn’t help.

Now, with daily volumes in the billions of dollars, even multi-trillion-dollar capital pools cannot meaningfully allocate a portion into Bitcoin—the liquidity still isn’t sufficient for them. If they began deploying hundreds of millions or billions per day, it would be enough to shift supply and demand heavily toward buyers and dramatically push prices higher. Since its inception, the Bitcoin ecosystem needed to reach certain liquidity thresholds before attracting attention from larger capital pools. It’s like leveling up.

So who will buy when Bitcoin exceeds $100,000 or $200,000? Who are the entities waiting to buy until Bitcoin becomes that strong? At $100,000 per Bitcoin, each sat is worth 0.1 cents.

Just as the price of a 400-ounce gold bar (the delivery standard) doesn’t matter to most people, the price of a whole Bitcoin doesn’t matter either. What matters is the overall network scale, liquidity, and functionality. What matters is whether, over the long term, their share of the network maintains or enhances its purchasing power.

Like any asset, Bitcoin’s price is a function of supply and demand.

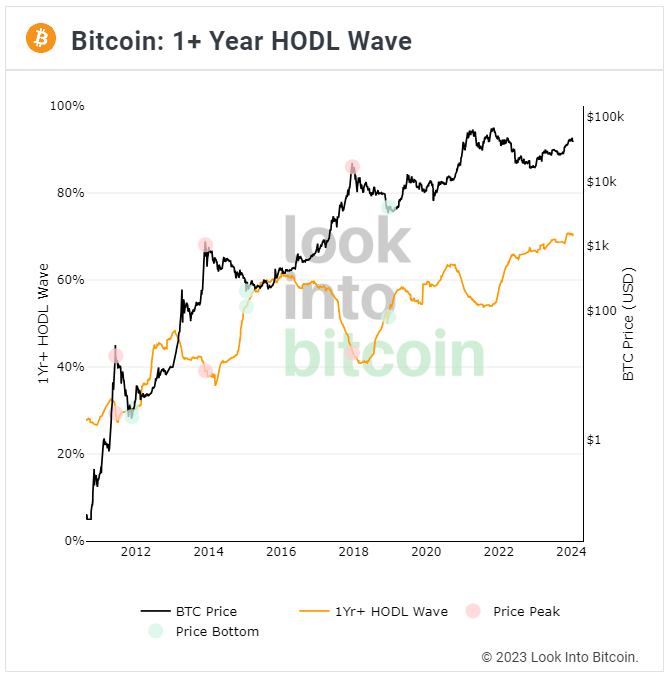

Supply is fixed, but at any given moment, part of it may be held by weak hands or strong hands. During bull markets, many new investors excitedly buy while some long-term holders reduce positions and sell to these newcomers. During bear markets, many recent buyers sell at a loss, while more committed holders rarely sell. Supply shifts from weak hands seeking quick profits to strong hands unwilling to let go easily. The chart below shows the percentage of Bitcoin that hasn’t moved on-chain for over a year, alongside Bitcoin’s price:

When Bitcoin’s supply is tight, only a small amount of new demand and fresh capital inflow can dramatically increase the price because existing holders won’t generate a large supply response. In other words, even if the price surges, it won’t encourage mass selling from over 70% of tokens held for more than a year. But where does this demand come from?

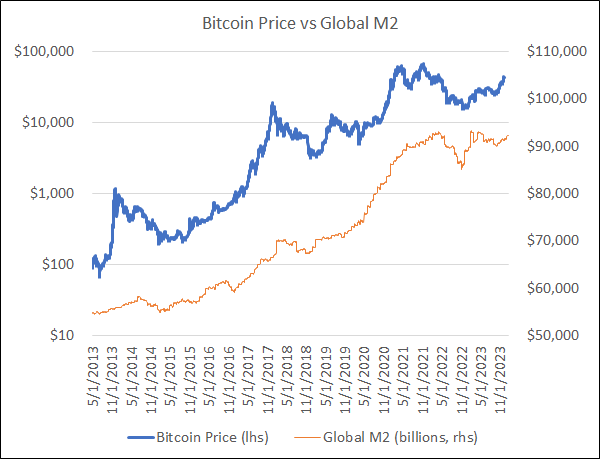

Generally, I find the factor most correlated with Bitcoin demand is the U.S. dollar-denominated global broad money supply. The first part—global money supply—is a measure of global credit growth and central bank money printing. The second part, denominated in U.S. dollars, matters because the dollar is the global reserve currency and thus the primary unit of account for global trade, contracts, and debt. When the dollar strengthens, countries’ debts become harder. When the dollar weakens, it softens national debts. Dollar-denominated global broad money acts as a key global liquidity indicator. How quickly are fiat units being created? How strong is the dollar relative to other currencies in global markets?

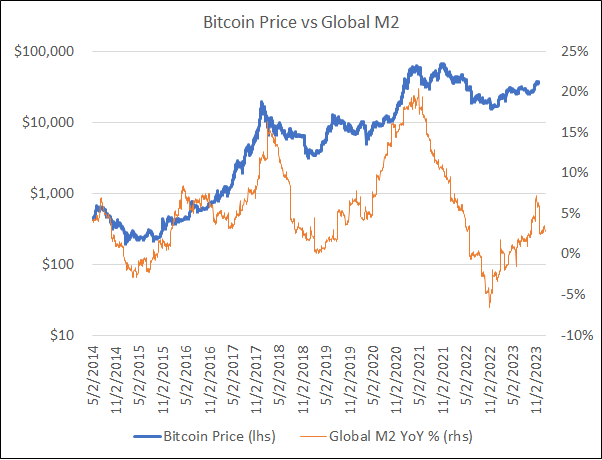

Look Into Bitcoin offers a macro data suite, which includes a chart showing Bitcoin’s price versus the rate of change in global broad money. I used this to create my own chart:

We’re comparing exchange rates between two different currencies here. Bitcoin is smaller, but over time, due to its halving issuance schedule and 21 million coin cap, it becomes increasingly hard. The dollar is vastly larger and experiences periods of strength and weakness, but mostly it weakens with growing supply and only briefly cycles into strength. Bitcoin’s fundamentals and the dollar’s fundamentals (global liquidity) both influence their exchange rate over time.

Therefore, when evaluating Bitcoin’s market cap and liquidity, I assess it against global broad money and other major assets over time. Its booms and busts are fine—it’s going from zero to an unknown future, complete with volatility. Price increases attract leverage, eventually leading to crashes. For Bitcoin to achieve widespread adoption, it must continuously go through cycles and shed leverage and cyclical collateral.

Bitcoin’s notorious volatility is unlikely to diminish significantly unless it becomes much more liquid and widely held. Beyond more time, more adoption, more liquidity, better understanding, and improved user experience for wallets, exchanges, and other applications, there’s no other way to address Bitcoin’s volatility. The asset itself changes slowly, while the world’s perception of it—and the process of adding and removing leverage on top of it—goes through manic and depressive cycles.

What concerns me? If global liquidity rises persistently over the long term but Bitcoin’s price remains stagnant, or if global liquidity trends upward yet Bitcoin fails to make new highs over multi-year periods. Then we’d have to ask tough questions about why the Bitcoin network isn’t capturing market share over extended durations. But so far, by this metric, it’s quite healthy.

Fungibility and Convertibility

Bitcoin has undergone multiple narrative shifts during its 15-year lifespan, and interestingly, nearly all were discussed back in 2009 and 2010 on the Bitcoin Talk forum by Satoshi Nakamoto, Hal Finney, and many others. Since then, Bitcoin markets have surged around different use cases for the network.

It’s like the parable of the blind men and the elephant. Three blind men touch an elephant—one feels the tail, one the side, one the tusk. They argue about what they’ve touched, yet they’re all touching different parts of the same object.

A recurring topic in the Bitcoin ecosystem is whether it’s a payment method or a savings vehicle. The answer is obviously both, though emphasis sometimes shifts. Satoshi’s original whitepaper described peer-to-peer electronic cash, though in his early posts he also discussed central bank currency devaluation and how Bitcoin resists such devaluation due to its fixed supply (i.e., as a savings tool). After all, money serves multiple functions.

Do I contradict myself?

Very well, then I contradict myself.

I am large, I contain multitudes.

——Walt Whitman

Payments and savings are both important and complementary. Because Bitcoin was primarily designed as a low-throughput network (to maximize decentralization), it mainly functions as a settlement layer. Actual everyday consumer transactions need to happen on higher layers (like Layer 2).

-

Bitcoin’s ability to be sent from any internet user to any other anywhere in the world is a critical component of its utility. It gives holders the ability to make permissionless, censorship-resistant payments. Indeed, its first major use case came over a decade ago when WikiLeaks was cut off by major payment platforms. WikiLeaks then turned to Bitcoin to continue receiving donations. Democratic and human rights advocates in authoritarian regimes have used it to bypass bank freezes. People use it to evade unjust capital controls that attempt to lock them permanently into rapidly depreciating developing-nation currencies.

-

Likewise, Bitcoin’s 21 million supply cap and immutability make its rule set credible (including the supply cap), which is another reason it’s attractive. Most currencies see infinite supply growth over time, and even gold’s supply increases by about 1.5% annually on average, but Bitcoin’s doesn’t. If people don’t want to hold it but instead repeatedly convert between fiat and Bitcoin for short-term settlements/payments, that adds friction, cost, and external scrutiny to the network. The best way to use Bitcoin for payments or receive Bitcoin payments is when you intend to hold it long-term.

Thus, the combination of payment and savings functionality is key. The crucial concept here is optionality. If you hold Bitcoin long-term, you have the option to take that wealth anywhere in the world or make permissionless, censorship-resistant payments to anyone connected to the internet, if you wish or need to. Your money can’t be unilaterally frozen or devalued by a bank or government with a stroke of a pen. It isn’t confined to narrow jurisdictions—it’s global. These features may not matter much to many Americans, but they’re profoundly important to people worldwide.

Many countries impose capital gains taxes on Bitcoin (and most other assets), meaning people must pay taxes based on cost basis if they sell or spend it, and must track accounting. This is a key part of how nations maintain monetary monopolies. As Bitcoin achieves wider adoption and some countries adopt it as legal tender, this may fade away. But for now, this tax reality exists in most places, reducing Bitcoin’s appeal for consumption compared to fiat in many cases. That’s partly why I hesitate to spend much of mine. Then again, I live in a jurisdiction with minimal payment friction in the fiat system.

Gresham’s Law states that under fixed exchange rates (or I’d argue, other frictions like capital gains taxes), people spend the weaker currency first and hoard the stronger one. For example, in Egypt, if someone holds both dollars and Egyptian pounds, they’ll spend the pounds and save the dollars. Or, if every Bitcoin transaction I make requires taxes while my dollar transactions don’t, I’ll usually spend dollars and keep my Bitcoin. Egyptians can spend dollars, and I can spend Bitcoin in many places, but we both choose not to.

Thier’s Law states that when a currency becomes extremely weak beyond a critical point, merchants stop accepting it and demand payment in a harder currency. At that point, Gresham’s Law reverses—people are forced to spend more. When a currency collapses entirely, those who saved in dollars in such countries often start spending dollars, which even replaces the weaker currency as a medium of exchange.

In most economic environments, it’s not just merchants selling goods and services that matter—money changers are also important. In Egypt or many developing nations, a restaurant might not accept dollars even though dollars are valuable appreciating items there. Sometimes you need to convert to local currency first to spend at official merchants, while informal merchants are usually more open to premium currency payments.

Suppose I bring a stack of physical dollars, a few South African Krugerrands, or some Bitcoin to a country, but no Visa card. How can I access local goods and services? I could find a merchant who directly accepts these currencies, or I could find a broker to exchange this hard money into local currency at fair local rates. With the latter approach, it’s like entering an amusement park or casino—I may need to convert real global money into the locale’s monopoly currency, then convert back to real global money when I leave. Sounds ironic, but that’s how it works.

In other words, what we need to know is a currency’s salability or convertibility—not just how many merchants directly accept it or how much merchant transaction volume it handles. Take the obvious example: very few people worldwide pay directly with gold, yet gold has high liquidity and convertibility. You can almost anywhere easily find buyers at fair market prices for recognizable gold coins. Thus, gold provides holders with substantial optionality. Bitcoin is similar in this regard but more portable globally.

Most fiat currencies have extremely high liquidity and salability domestically, accepted by nearly all merchants. But except for a few fiat currencies, none have significant salability or convertibility abroad. In this sense, they’re like arcade tokens or casino chips. For instance, my Egyptian pounds and Norwegian kroner are nearly useless in New Jersey—even finding somewhere easy to exchange them:

Egyptian and Norwegian banknotes

Roughly quantifying this:

-

Physical USD has about 10/10 convertibility in the U.S., 7/10 in some countries, maybe 5/10 in others. There’s a range, but overall, it’s usually the most salable currency globally today. Sometimes you can spend it directly, sometimes you must exchange it first, but either way liquidity is typically ample.

-

Most physical currencies have 10/10 convertibility in their home country but only 1/10 or 2/10 elsewhere. Outside their jurisdiction, it takes considerable time and possibly high discounts to find willing traders. It’s like arcade tokens.

-

Gold has about 6/10 convertibility almost anywhere, making it one of the few bearer assets as convertible as the dollar. You can’t use it as easily as a country’s local fiat, and overall spending volume is small, but in nearly any country you can easily exchange it for liquid value. Gold is a globally recognized form of liquid and fungible value.

-

Bitcoin has about 6/10 convertibility in many urban centers worldwide—in this sense similar to gold—but drops to about 2/10 in many rural areas, akin to fiat outside its monopoly boundary. But it’s on a strong upward trend and has made incredible progress from nothing in just 15 years. Moreover, in most regions it can be converted online into mobile top-ups, locally spendable digital gift cards, and other value forms, so the total number of offline and online conversion options for Bitcoin holders is meaningful.

To me, the right question is “If I carry Bitcoin with me, can I easily spend or cash out its value?” In urban centers of many countries—developing ones like South Africa, Costa Rica, Argentina, or Nigeria, or basically any developed nation—the answer is a fairly loud “yes.” In other countries like Egypt, this hasn’t truly materialized yet.

Over any given multi-year period so far, Bitcoin has certainly become more convertible.

The Rise of Bitcoin Hubs

To me, the most promising trend is the growth of many small Bitcoin communities worldwide. El Zonte in El Salvador is one, which caught the attention of the country’s president. But there are other community hotspots too—Costa Rica’s Bitcoin Jungle, Guatemala’s Bitcoin Lake, South Africa’s Bitcoin Ekasi, Lugano in Switzerland, Madeira Island F.R.E.E., and many other areas becoming dense zones of Bitcoin usage and acceptance. Bitcoin salability and convertibility are quite high in these places. Bitcoin hubs keep emerging.

Additionally, Ghana has hosted the Africa Bitcoin Conference for two consecutive years, led by a woman named Farida Nabourema. She’s a Togolese exile and democracy advocate who deeply understands financial repression as a tool of authoritarianism and is also a critic of France’s neocolonial monetary system across a dozen African nations. Indonesia now regularly hosts Bitcoin conferences led by a woman named Dea Rezkitha. Bitcoin conferences happen worldwide.

There are also small organizations like Bitcoin Commons in Austin, Texas; Bitcoin Park in Nashville; Pubkey in New York; and Real Bedford in the UK—all local Bitcoin hubs. Having a dedicated Bitcoin community or regular meetup in a specific city is becoming increasingly common. Sites like BitcoinerEvents.com help you find them, and they can also serve as channels to convert Bitcoin.

There are also apps to help you find Bitcoin-accepting merchants nearby. For example, BTCMap.org lets you locate merchants worldwide that accept Bitcoin. Both the 2023 BTC Prague Conference and the 2023 Africa Bitcoin Conference featured the Fedi app. Beyond serving as a Bitcoin wallet, the app provided schedules for major conference events, including interactive maps showing locations of merchants accepting Bitcoin payments—such as AI assistants using Lightning Network micropayments. (Disclosure: I’m an investor in Fedi via Ego Death Capital.)

Technical Security and Decentralization

My friend and colleague Jeff Booth often begins descriptions of his outlook for Bitcoin’s future and macroeconomic impact with, “as long as Bitcoin remains secure and decentralized.” In other words, it’s an if/else view grounded in the network continuing to operate as it has over the past 15 years, preserving the characteristics that give Bitcoin value into the future.

Bitcoin isn’t magic. It’s a distributed network protocol. To continue delivering value, it must withstand opposition and attacks and remain the best, most liquid option. The idea of Bitcoin isn’t enough to make a real difference in anything—the reality of Bitcoin is what matters. If Bitcoin suffers a catastrophic hack or becomes centralized (permissioned/censorable), it would lose its current use cases, and its value would partially or entirely vanish.

Beyond network effects and associated liquidity, focus on security and decentralization largely differentiates Bitcoin from other cryptocurrency networks. It sacrifices performance in nearly every other category—speed, throughput, programmability—to be as simple, lean, secure, robust, and decentralized as possible. Its design maximizes these traits. All additional complexity must be built on layers atop Bitcoin, not embedded into the base layer, because embedding such features into the base layer would sacrifice the performance of key attributes like security and decentralization.

Therefore, monitoring Bitcoin’s security and decentralization levels is crucial when building and maintaining long-term themes around the network’s value and utility.

Security Analysis

Bitcoin has a remarkably strong security record as an emerging open-source technology, though not perfect. As I wrote in *Broken Money*, here are some notable technical issues it has faced so far:

In 2010, when Bitcoin was brand new and had almost no market price, a node client inflation bug occurred, which Satoshi Nakamoto fixed with a soft fork.

In 2013, due to oversight, a Bitcoin node client update accidentally became incompatible with prior (and widely used) node clients, causing an unintended chain split. Within hours, developers analyzed the issue and instructed node operators to revert to the earlier client, resolving the split. Over the subsequent decade-plus, the Bitcoin network maintained perfect 100% uptime. During this period, even Fedwire experienced outages failing to achieve 100% uptime.

In 2018, another inflation vulnerability was accidentally added to the Bitcoin node client. However, developers identified and carefully fixed the issue before exploitation, so it caused no practical problems.

In 2023, people began using SegWit and Taproot soft fork upgrades in ways developers hadn’t anticipated, including inserting images into signature sections of the Bitcoin blockchain. While not a bug itself, it revealed risks of code being used in unforeseen ways, meaning conservative caution is needed when executing future upgrades.

Bitcoin faces the “Year 2038 problem” common to many computer systems. By 2038, the 32-bit integer used for Unix timestamps in many systems will run out of seconds, causing errors. However, Bitcoin uses unsigned integers, so it won’t run out until 2106. This can be solved by updating timestamps to 64-bit integers or placing block height into a 32-bit integer. As far as I understand, this might require a hard fork—meaning backward-incompatible upgrades. Practically this shouldn’t be hard since it’s clearly necessary and can be done years or decades before the issue arises, but it could open a window of vulnerability. One possible method is releasing a backward-compatible update that activates only when the integer runs out, solving the problem.

– Broken Money, Chapter 26

Bitcoin can indeed recover from technical issues. The basic solution is for node operators on the decentralized network to roll back to updates before the bug existed and reject the problematic new update. Yet we must imagine worst-case scenarios. If a technical flaw goes unnoticed for years, becomes part of a widespread node network, and is later discovered and exploited, that’s a far more serious, catastrophic issue. Though perhaps not irrecoverable, it would be a severe blow.

As Bitcoin’s codebase persists for years or even decades, it becomes more robust and benefits from the Lindy Effect.

Overall, the rate of major bugs has declined over time, and the fact that the network has maintained 100% uptime since 2013 is compelling.

Decentralization Analysis

We can treat node distribution and mining distribution as key variables measuring decentralization. A widely distributed node network makes changing network rules very difficult, as each node enforces rules for its users. Similarly, a widely distributed mining network makes transaction censorship harder.

Bitnodes identifies over 16,000 reachable Bitcoin nodes. Bitcoin Core developer Luke Dashjr estimates the total number, including privately run nodes, exceeds 60,000.

By comparison, Ethernodes identifies about 6,000 Ethereum nodes, roughly half hosted on cloud providers rather than running locally. And because Ethereum nodes consume too much bandwidth for private operation, this may be close to the actual number.

So Bitcoin is quite strong in node distribution.

Bitcoin miners cannot change core protocol rules, but they can decide which transactions enter the network or not. Thus, mining centralization increases the risk of transaction censorship.

The largest publicly listed miner, Marathon Digital Holdings (MARA), controls less than 5% of network hash power. Several other private miners are roughly similar in size. Various public and private miners hold 1–2%, and many others control smaller shares. In other words, mining is indeed quite decentralized—even the largest participants command only a tiny fraction of network resources.

Since China banned Bitcoin mining in 2021, the U.S. has become the largest mining jurisdiction, though estimated to host less than half of total hash power. Ironically, China remains the second-largest mining jurisdiction because mining is hard to eradicate even under authoritarian regimes. Canada, Russia, and other energy-rich nations have large-scale mining infrastructure, and dozens of countries host smaller mining operations.

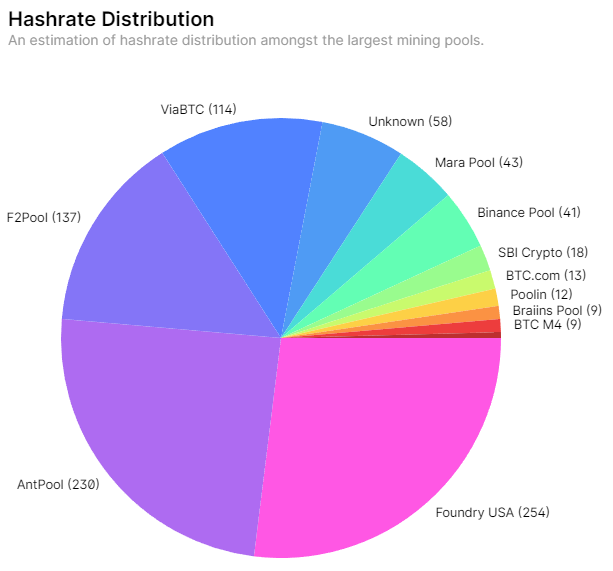

Mining companies typically distribute their hash power to mining pools. Currently, pools are quite centralized—two pools together control about half of transaction processing, and the top ten pools control nearly all transaction processing. I see this as an area needing improvement:

Source: Blockchain.com

However, important caveats exist. First, mining pools don’t host the mining hardware—a crucial distinction. If a pool develops issues, miners can easily switch to another. So while several pools could jointly execute a brief 51% attack, their ability to sustain such an attack may be very weak. Second, Stratum V2 has recently launched, giving miners greater control over block construction instead of letting pools do all the work.

The physical mining supply chain is also quite concentrated. TSMC and a few other foundries are key bottlenecks for producing most chip types, including ASICs used by Bitcoin miners. In fact, I’d argue pool centralization is an overestimated risk, while semiconductor foundry centralization is an underestimated risk.

Overall, active mining hardware ownership is highly dispersed, but the fact that certain countries host large numbers of miners, some pools concentrate significant hash power from them, and the mining supply chain has centralized aspects—all weaken the mining industry’s decentralization. I believe mining is an area that could benefit from more development and attention, fortunately with the most important variables (hardware ownership and physical distribution) being highly decentralized.

User Experience

If Bitcoin is technically difficult to use, it remains confined to programmers, engineers, theorists, and advanced users willing to invest time learning it. Conversely, if it becomes nearly effortless to use, it can spread more easily to ordinary people.

Looking back at cryptocurrency exchanges from 2013–2015, they appear very crude. Today, buying Bitcoin through reputable exchanges and brokers is generally easier with simpler interfaces. Early on, there were no dedicated Bitcoin hardware wallets; people usually had to figure out how to manage keys on their own computers. Most stories of “lost Bitcoin” heard in media come from that early era when Bitcoin’s value wasn’t high enough for people to pay close attention, and key management was harder.

Over the past decade, hardware wallets have become more common and user-friendly. Software wallets and interfaces have also improved significantly.

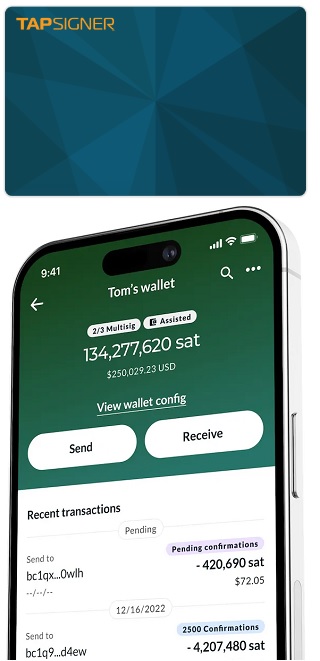

One of my favorite recent combinations is Nunchuk + Tapsigner, which works well for small amounts of Bitcoin. Tapsigner is a $30 NFC wallet that securely stores private keys offline at low cost, while Nunchuk is a mobile and desktop wallet compatible with multiple hardware wallet types, including Tapsigner for moderate Bitcoin amounts or full-featured hardware wallets for larger holdings.

Decades ago, learning to use a checkbook was an essential skill. Today, many people get Bitcoin/crypto wallets before getting bank accounts. Managing public/private key pairs may become a more routine part of life—for managing funds and signing to distinguish authentic social content from fake content. It’s easy to learn, and many will grow up surrounded by this technology.

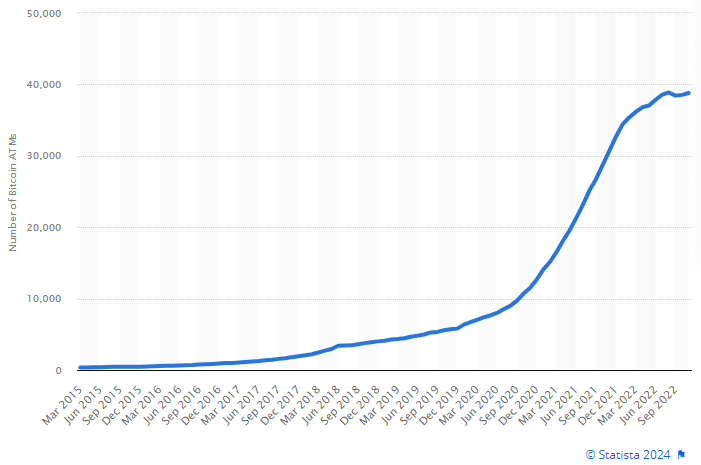

According to Statista, the number of global Bitcoin ATMs increased over 100-fold from 2015 to 2022:

Beyond ATMs, voucher-based purchases have increased, which I believe is one reason ATM numbers have recently plateaued. Azteco launched in 2019 and raised $6 million in seed funding in 2023 led by Jack Dorsey. Azteco vouchers can be bought with cash at hundreds of thousands of retail and online platforms—especially in developing nations—then redeemed for Bitcoin.

The Lightning Network has steadily evolved over the past six years, reaching substantial liquidity levels by the end of 2020.

Sites like Stacker News and communication protocols like Nostr have integrated Lightning, ultimately merging value transfer with information transfer. Novel browser extensions like Alby make it easy to use Lightning across multiple websites via one wallet and can replace usernames/passwords as signature methods in many scenarios.

Overall, using the Bitcoin network has become easier and more intuitive over time, and judging from what I see as a venture investor in this space, this trend will continue in coming years.

Legal Acceptance and Global Recognition

“But what if governments ban it?” Since Bitcoin’s inception, this has been a common objection. After all, governments enjoy state-issued currency monopolies and capital controls.

Yet in answering this, we must ask: “Which governments?” There are about 200. The game theory is such that if one country bans it, another can gain new business by inviting people to build together. El Salvador now recognizes Bitcoin as legal tender, and some other nations are using sovereign wealth funds to mine Bitcoin.

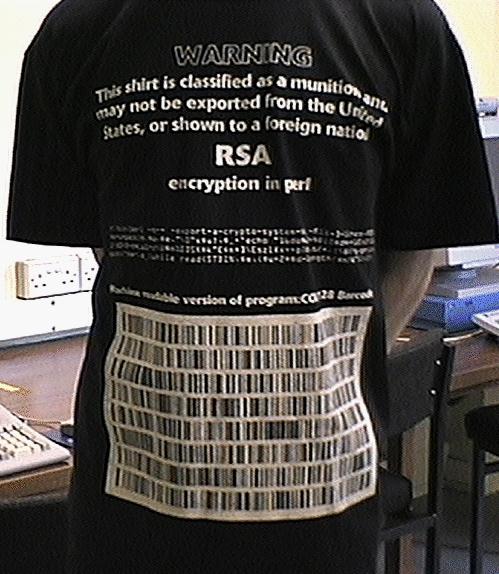

Moreover, some things are genuinely hard to stop. Back in the early 1990s, Phil Zimmerman created Pretty Good Privacy (PGP), an open-source encryption program. It allowed people to send private messages over the internet—something most governments disliked. After his open-source code spread overseas, the U.S. federal government launched a criminal investigation against Zimmerman for “unlicensed export of munitions.”

In response, Zimmerman published his full open-source code in a book, protected under the First Amendment. After all, it was merely a collection of text and numbers he chose to express to others. Some people, including Adam Back (creator of Hashcash, which eventually became Bitcoin’s proof-of-work mechanism), even began printing various encryption codes on T-shirts, with warnings like “This shirt is classified as a munition; exporting it or showing it to foreigners is illegal.”

The U.S. federal government did drop the criminal case against Zimmerman and changed encryption regulations. Encryption became a key part of e-commerce, as online payments required secure encryption, so if the U.S. government overreached, much economic value might be delayed or shifted abroad.

In other words, these protests succeeded by using the rule of law against government overreach, highlighting the absurdity and impracticality of trying to restrict concise, easily transmissible information. Open-source code is just information, and information is hard to suppress.

Similarly, Bitcoin is free open-source code, making it hard to eliminate. Even restricting hardware is difficult—China banned Bitcoin mining in 2021 but remains the second-largest mining jurisdiction, clearly showing how hard it is to prohibit. Software is even stickier.

Many countries have flip-flopped on banning Bitcoin or struggled with their own rule of law and separation of powers. In relatively free nations, governments aren’t monolithic. Some officials or representatives like Bitcoin; others don’t.

In 2018, India’s central bank banned banks from engaging in crypto-related businesses and lobbied the government to fully ban cryptocurrency use. But in 2020, India’s Supreme Court ruled against this, restoring the private sector’s right to innovate with the technology.

In early 2021, amid a decade of double-digit inflation in its national currency, Nigeria’s central bank banned banks from interacting with crypto, though it didn’t try to outlaw it publicly—because that would be hard to enforce. Instead, it launched the eNaira central bank digital currency and imposed stricter withdrawal limits on physical cash, attempting to push people into its centralized digital payment system. During the ban, Chainalysis assessed that Nigeria had the world’s second-highest cryptocurrency adoption rate (mainly stablecoins and Bitcoin), especially the highest peer-to-peer transaction volume—how they bypassed bank blocks. By late 2023, after nearly three years of ineffective bans, Nigeria’s central bank reversed course and allowed banks to interact with crypto under compliance rules.

In 2022, facing triple-digit inflation, Argentine

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News