Vitalik's Latest Article: Exploring the Future and Challenges of ZK-EVM

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik's Latest Article: Exploring the Future and Challenges of ZK-EVM

ZK-EVM aims to reduce redundant implementation of Ethereum protocol features by L2 projects and improve their efficiency in verifying Ethereum blocks.

Author: Vitalik Buterin

Translation: 1912212.eth, Foresight News

Layer 2 EVM protocols on Ethereum, including optimistic rollups and ZK rollups, rely on EVM validation. However, this requires trusting a large codebase, exposing these VMs to potential hacking if bugs exist within it. Moreover, even ZK-EVMs aiming for full equivalence with the L1 EVM require some form of governance to replicate changes from the L1 EVM into their own implementations.

This situation is suboptimal because these projects are duplicating functionality already present in the Ethereum protocol—governance of which already handles upgrades and bug fixes. Verifying Layer 1 Ethereum blocks is essentially what a ZK-EVM does! Furthermore, in the coming years, we expect light clients to become increasingly powerful, soon reaching the point where ZK-SNARKs can fully verify Layer 1 EVM execution. At that stage, the Ethereum network will effectively construct a built-in ZK-EVM. Hence, the question arises: why not make this native ZK-EVM also usable by rollups?

This article outlines several possible designs for such a "built-in ZK-EVM," discussing trade-offs, design challenges, and reasons for avoiding certain directions. The benefits of implementing protocol-level features must be weighed against the advantages of leaving things to the ecosystem and keeping the base protocol simple.

What key properties do we want from a built-in ZK-EVM?

-

Basic functionality: block verification. The protocol feature (currently unspecified as an opcode, precompile, or other mechanism) should accept at least a pre-state root, a block, and a post-state root as inputs, verifying that the post-state root is indeed the result after executing the block.

-

Compatibility with multiple Ethereum clients. This means avoiding reliance on a single proof system, allowing different clients to use different ones. This leads directly to the following points:

-

Data availability requirements: For any EVM execution proven using the built-in ZK-EVM, we want underlying data to be available so provers using alternative proof systems can re-prove execution, and dependent clients can validate newly generated proofs.

-

Proofs exist outside the EVM and block data structure: The built-in ZK-EVM function should not take SNARKs as inputs inside the EVM, since different clients would expect different types of SNARKs. Instead, it might resemble blob verification: transactions could include claims (pre-state, block body, post-state) requiring proof; an opcode or precompile could access the content of these claims, while client consensus rules separately check data availability and proof existence for each claim.

-

Audibility: If any execution is proven, we want the underlying data to be accessible so users and developers can inspect it when issues arise. In practice, this adds another reason why data availability requirements are critical.

-

Upgradability: If a ZK-EVM scheme is found to have a bug, we should be able to fix it quickly—ideally without requiring a hard fork. This reinforces why proofs should reside outside the EVM and block data structures.

-

Support for nearly all EVM variants. One appeal of Layer 2s is innovation at the execution layer and extending the EVM. It would be beneficial if a given L2’s VM, even slightly different from the standard EVM, could still leverage the native protocol ZK-EVM for common parts while relying on its own code for divergent aspects. This could be achieved by designing the ZK-EVM feature to allow callers to specify bitfields, opcodes, or addresses handled via externally provided tables rather than the EVM itself. We could also make gas costs partially modifiable.

"Open" vs. "Closed" multi-client systems

The "multi-client principle" may be the most subjective requirement on this list. One option is to abandon it in favor of focusing on a specific ZK-SNARK scheme, simplifying design at the cost of representing a greater philosophical departure from Ethereum's long-standing multi-client ethos, along with increased risk. This path might become more viable if formal verification techniques improve significantly in the future, but currently appears too risky.

Another option is a closed multi-client system, where a fixed set of proof systems is known in-protocol. For example, we might decide to support three ZK-EVMs: PSE ZK-EVM, Polygon ZK-EVM, and Kakarot. A block would only be valid if two out of these three provide proofs. While better than a single proof system, this reduces system adaptability, as users must maintain validators for every existing proof system, and inevitably involves political governance processes to add new ones.

This motivates my preference for an open multi-client system, where proofs are placed "outside the block" and verified independently by clients. Individual users can use whichever client they prefer, as long as at least one prover generates a proof for that system. Proof systems gain influence by convincing users to run them, not by persuading protocol governance. However, this approach comes with higher complexity costs, as we will see.

What key properties do we want from ZK-EVM implementations?

Beyond basic functional correctness and security guarantees, the most important property is speed. While we could design an in-protocol ZK-EVM feature that is asynchronous, returning results for each claim only after N slots of delay, it would be much simpler if we could reliably generate proofs within seconds—making every block self-contained regardless of what happens within it.

Although generating proofs for Ethereum blocks today takes many minutes or hours, there is no theoretical obstacle to massive parallelization: we can always combine enough GPUs to prove different parts of a block execution separately, then aggregate proofs using recursive SNARKs. Additionally, hardware acceleration via FPGA and ASIC could further optimize proving. Yet achieving this remains a formidable engineering challenge.

What might an in-protocol ZK-EVM feature look like?

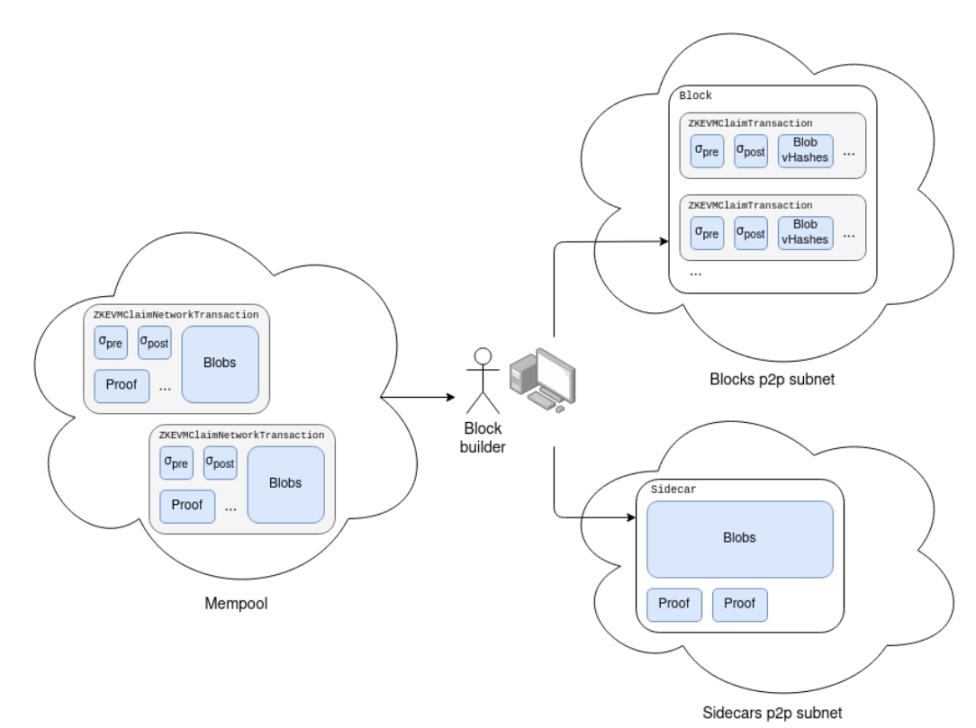

Similar to EIP-4844 blob transactions, we introduce a new transaction type containing ZK-EVM claims:

class ZKEVMClaimTransaction(Container):

pre_state_root: bytes32

post_state_root: bytes32

transaction_and_witness_blob_pointers: List[VersionedHash]

As with EIP-4844, the object passed through the mempool would be a modified version of the transaction:

class ZKEvmClaimNetworkTransaction(Container):

pre_state_root: bytes32

post_state_root: bytes32

proof: bytes

transaction_and_witness_blobs: List[Bytes[FIELD_ELEMENTS_PER_BLOB * 31]]

The latter can be converted into the former, but not vice versa. We also extend the block sidecar object (introduced in EIP-4844) to include a list of proofs claimed in the block.

In practice, we may want to split the sidecar into two separate sidecars—one for blobs and one for proofs—and establish separate subnets for each proof type (and additional subnets for blob types).

At the consensus layer, we add validation rules: a block is only accepted if the client sees a valid proof for each claim in the block. The proof must be a ZK-SNARK proving that the concatenation of transaction_and_witness_blobs forms a sequence of (Block, Witness) pairs, and that executing the block over the witness starting from pre_state_root

(i) is valid, and

(ii) produces the correct post_state_root. Clients could optionally wait for M-of-N proofs of different types.

Note that block execution itself can be viewed simply as one of the triples to be checked alongside those provided in the ZKEVMClaimTransaction object (σpre,σpost,Proof). Thus, a user’s ZK-EVM implementation can replace their execution client; the execution client will still be used by

(i) provers and block builders, and

(ii) nodes that care about indexing and storing data locally.

Furthermore, because this architecture separates execution from verification, it may offer greater flexibility and efficiency for different roles within the Ethereum ecosystem. For instance, provers can focus solely on generating proofs without worrying about execution details, while execution clients can be optimized for specific user needs, such as fast syncing or advanced indexing capabilities.

Verification and Re-proving

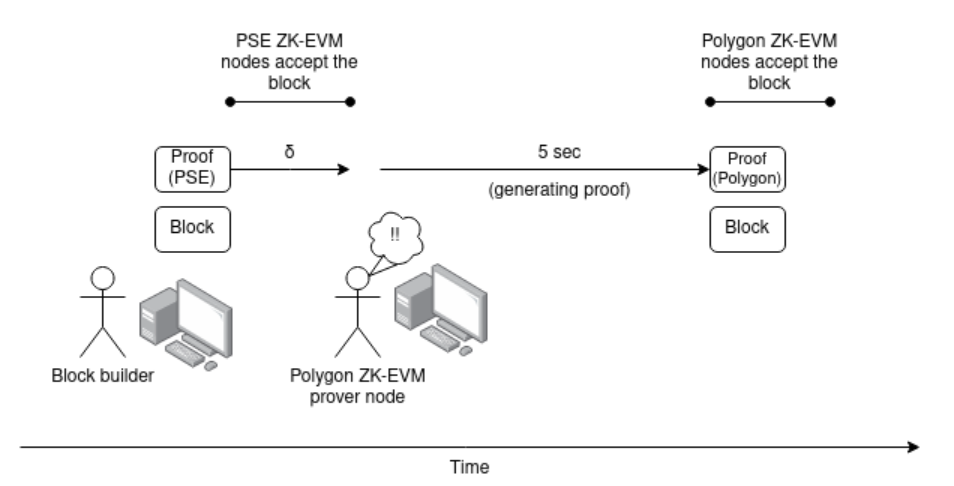

Suppose two Ethereum clients exist—one using the PSE ZK-EVM and another using the Polygon ZK-EVM—and both implementations have evolved to the point where they can prove Ethereum block execution within 5 seconds, with enough independent volunteers running hardware for each proof system to generate proofs.

Unfortunately, because individual proof systems are not formally established in-protocol, they cannot receive incentives within the protocol. However, we expect the cost of running provers to be low compared to research and development, so public goods funding institutions could easily subsidize provers.

Suppose someone publishes a ZKEvmClaimNetworkTransaction but only includes a proof from the PSE ZK-EVM. A prover node using the Polygon ZK-EVM sees this, computes its own proof, and re-publishes the object with the Polygon ZK-EVM proof attached.

This increases the maximum total delay between the earliest honest node accepting a block and the latest honest node accepting the same block from δ to 2δ+Tprove (assuming Tprove<5s).

However, the good news is that if we adopt single-slot finality, we can almost certainly pipeline this additional delay together with the inherent multi-round consensus latency in SSF. For example, in this four-subslot proposal, the "head vote" step might only need to check basic block validity, while the "finalize and seal" step requires the presence of a proof.

Extension: Supporting "almost-EVMs"

A desirable goal for the ZK-EVM functionality is supporting "almost-EVMs": EVMs with added features. This could include new precompiles, new opcodes, contracts capable of running in either the EVM or a completely different VM (e.g., WASM in Arbitrum Stylus), or even multiple parallel EVMs communicating via synchronous channels.

Some modifications can be supported simply: we can define a language allowing ZKEVMClaimTransaction to pass a full description of modified EVM rules. This could apply to:

-

Custom gas cost tables (users cannot reduce gas costs, but they can increase them)

-

Disabling certain opcodes

-

Setting block numbers (implying different rules based on hard forks)

-

Setting flags to activate standardized sets of EVM changes intended for L2 use but not applicable to L1, or other simpler changes

To allow users to more openly add new functionalities—such as introducing new precompiles (or opcodes)—we could add a way within the blob portion of ZKEVMClaimNetworkTransaction to include precompile input/output transcripts:

class PrecompileInputOutputTranscript(Container):

used_precompile_addresses: List[Address]

inputs_commitments: List[VersionedHash]

outputs: List[Bytes]

EVM execution would be modified as follows. An array called inputs is initialized as empty. Whenever an address in used_precompile_addresses is called, we append an InputsRecord(callee_address, Gas, input_calldata) object to inputs and set the call's RETURNDATA to outputs[i]. Finally, we verify that used_precompile_addresses was called exactly len(outputs) times and that inputs_commitments matches the commitment to the SSZ serialization of the generated inputs blob. Exposing inputs_commitments allows external SNARKs to prove relationships between inputs and outputs.

Note the asymmetry between inputs and outputs: inputs are stored hashed, while outputs are stored as raw bytes that must be provided. This is because execution must be performed by clients that only see inputs and understand the EVM. Since EVM execution already generates the inputs, they only need to verify that the generated inputs match the claimed ones—requiring just a hash check. However, outputs must be fully provided to them, necessitating full data availability.

Another useful feature might be allowing "privileged transactions" to be invoked from arbitrary sender accounts. These transactions could run between two others, or even within another (possibly also privileged) transaction, possibly calling precompiles. This could enable non-EVM mechanisms to callback into the EVM.

The design could be adapted to support new or modified opcodes, not just precompiles. Even with only precompiles, the design is very powerful. For example:

By setting used_precompile_addresses to include regular account addresses whose account objects in state have a certain flag set, and generating a SNARK proving its correct construction, we could support features like Arbitrum Stylus, where contracts can write their code in either EVM or WASM (or another VM). Privileged transactions could allow WASM accounts to callback into the EVM.

By adding external checks ensuring that input/output records and privileged transactions across multiple EVM executions match correctly, we could prove parallel systems of multiple EVMs communicating via synchronized channels.

Type 4 ZK-EVMs could operate via dual implementations: one compiling Solidity or another high-level language directly into a SNARK-friendly VM, and another compiling it into EVM bytecode and executing it in a prescribed ZK-EVM. The second (inevitably slower) implementation would only run when a fault prover submits a transaction claiming an error, and could collect a bounty if they demonstrate differing processing of a transaction.

Pure asynchronous VMs could be implemented by making all calls return zero and mapping calls to privileged transactions appended at the end of the block.

Extension: Supporting stateful provers

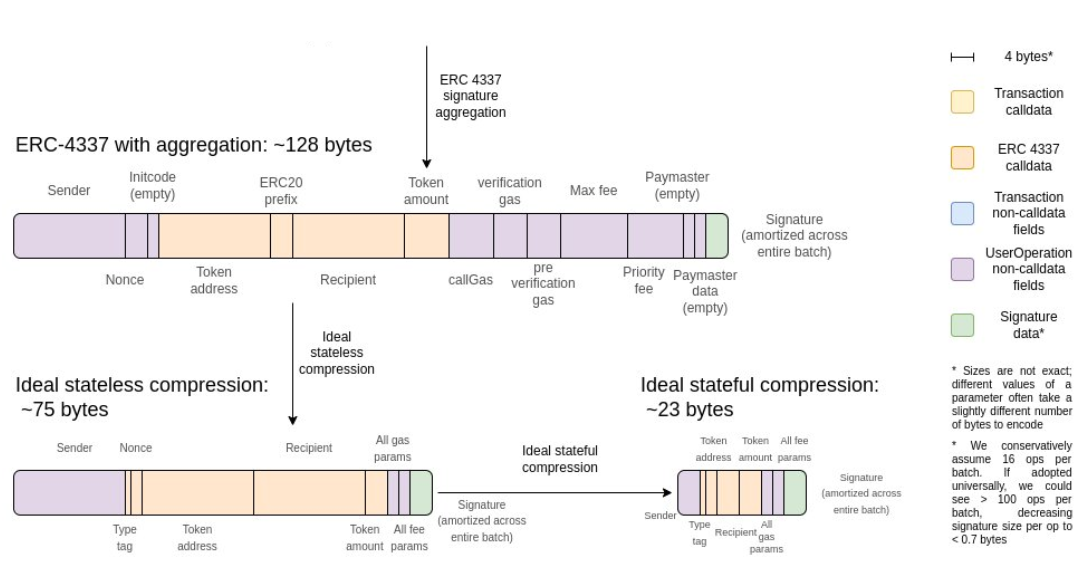

A challenge with the above design is that it is entirely stateless, leading to poor data efficiency. With ideal compression, stateful compression could make ERC20 transfers up to 3x more space-efficient than stateless-only approaches.

Additionally, stateful EVMs do not need to provide witness data. In both cases, the principle is the same: requiring data availability is wasteful when the data is already known to be available because it was input to or produced by prior EVM executions.

If we wish to make the ZK-EVM feature stateful, we have two options:

Require σpre to be either empty, a pre-declared list of key-value pairs with available data, or the σpost of some previous execution.

Add a blob commitment of receipts R generated by the block to the (σpre, σpost, Proof) tuple. Blob commitments referenced in ZKEVMClaimTransaction can be accessed during execution, including those representing blocks, witnesses, receipts, or even regular EIP-4844 blob transactions (possibly with time limits, referable via a series of instructions: “insert bytes N...N+k-1 from commitment i at position j in block + witness data”)

(1) Essentially means: instead of establishing stateless EVM verification, we establish EVM subchains.

(2) Effectively creates a minimal built-in stateful compression algorithm using previously used or generated blobs as a dictionary. Both place additional burden only on prover nodes—to store more information;

In case (2), this burden is easier to time-limit, whereas in case (1) it is harder.

Arguments for closed multi-prover systems and off-chain data

A closed multi-prover system, with a fixed number of proof systems in an M-of-N structure, avoids much of the above complexity. In particular, such a system does not need to ensure data exists on-chain. Additionally, a closed multi-prover system would allow ZK-EVM proofs of off-chain execution—making it compatible with EVM Plasma solutions.

However, closed multi-prover systems increase governance complexity and weaken audibility—costs that must be weighed against these advantages.

If we build ZK-EVM into the protocol, what role remains for L2 projects?

The EVM validation functionality currently implemented independently by L2 teams would be handled by the protocol, but L2 projects would still be responsible for many important functions:

-

Fast pre-confirmations: Single-slot finality may slow down L1 slot times, while L2s already provide services supported by pre-confirmations with latencies far below a single slot. This service will remain entirely under L2 control.

-

MEV mitigation strategies: These might include encrypted mempools, reputation-based sequencing, and other features that L1 is unwilling to implement.

-

EVM extensions: Layer 2 projects can introduce significant enhancements to the EVM, delivering substantial value to their users. This includes "almost-EVMs" and entirely different approaches, such as Arbitrum Stylus's WASM support and the SNARK-friendly Cairo language.

-

User and developer convenience: Layer 2 teams invest heavily in attracting users and projects into their ecosystems and making them feel welcome—earning rewards by capturing MEV and congestion fees within their networks. This relationship will continue.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News