Witnessing a Century of Transformation in the Middle East: Economic Innovation and China's Opportunities

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Witnessing a Century of Transformation in the Middle East: Economic Innovation and China's Opportunities

Great transformation contains great opportunities.

Author: Li Xiaotian

Recently, the world's attention has once again turned to the Middle East.

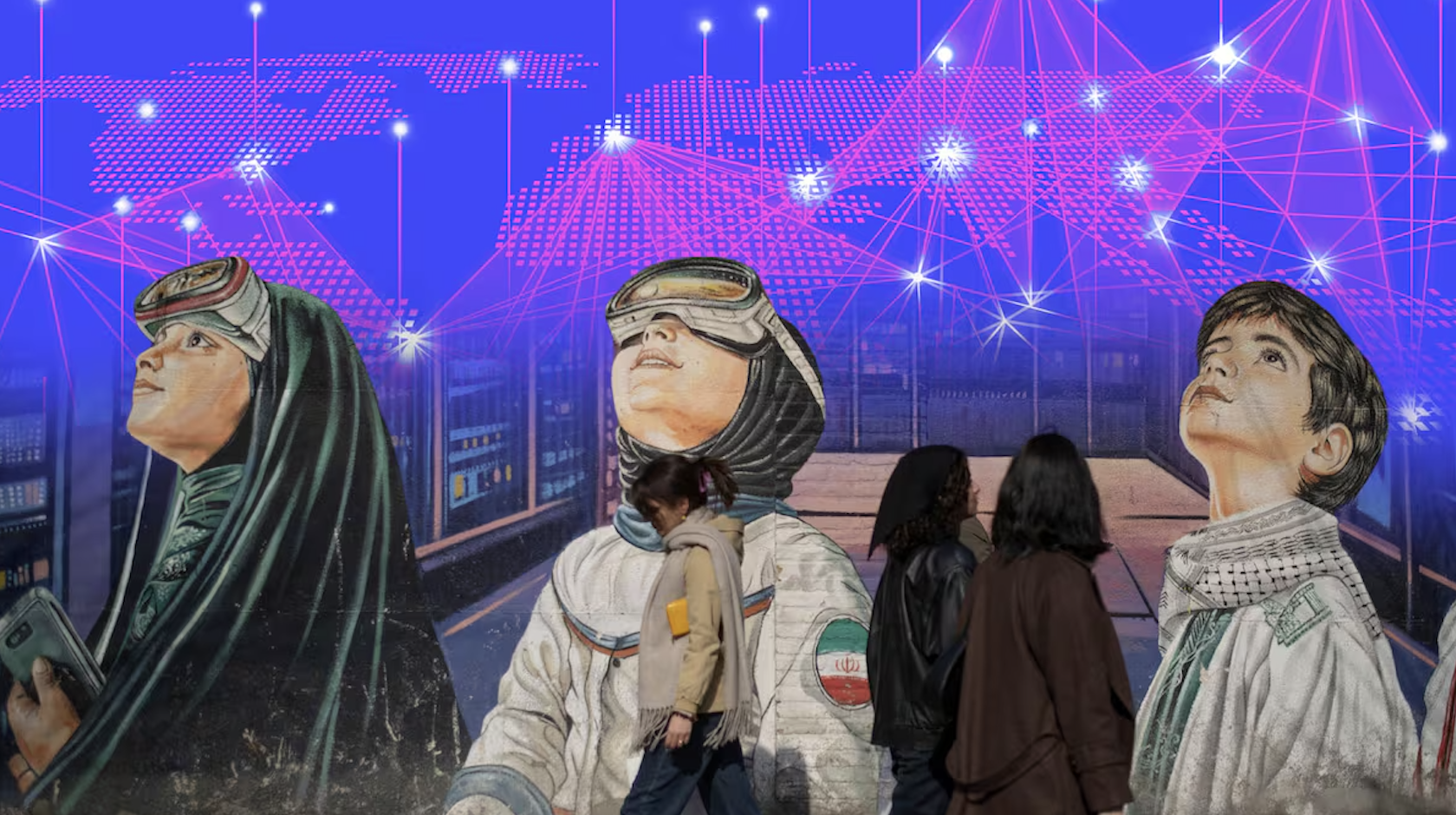

Located at the crossroads of Europe and Asia and rich in oil resources, the Middle East has long been a battleground for major powers. Its every move profoundly affects global stability and transformation. In the past, this region was often seen as mysterious by outsiders, with perceptions of Middle Eastern countries largely stuck in stereotypes such as "people swimming in oil wealth," "extremely conservative societies," and "industrially underdeveloped."

But in recent years, Middle Eastern nations led by Saudi Arabia have accelerated their pace of reform: In 2016, Saudi Arabia unveiled its national strategic roadmap “Vision 2030,” aiming to diversify its economy and reduce dependence on oil; in 2021, coinciding with the UAE’s 50th anniversary, it launched the “Next 50 Years National Development Strategy,” focusing on investment and entrepreneurship in digital economies and advanced technologies; Kuwait introduced its “Vision 2035,” Qatar its “Vision 2030,” Oman its “Vision 2040,” and Egypt its “Revitalization Plan.” Across social culture, economic industries, and foreign strategies, numerous Middle Eastern countries are undergoing profound transformations.

Great transformation brings great opportunities.

To help Chinese entrepreneurs who aspire to expand overseas deeply understand the changes and opportunities in the Middle East, from October 9 to 16,霞光社 (XiaGuang Society) launched its long-prepared SparkHub overseas exploration project titled “Mining Overseas: Encountering the Middle East.”

This trip, XiaGuang Society led more than ten entrepreneurs, business leaders, and renowned scholars focused on the Middle East market, traveling across key cities including Abu Dhabi (UAE), Dubai (UAE), and Riyadh (Saudi Arabia). We visited over ten companies based in the region, covering venture capital funds, tech industrial parks, new energy enterprises, mobile social platforms, logistics services, digital new infrastructure, web3 technology, and cross-border payments.

Route map of XiaGuang SparkHub’s Middle East expedition

Through on-site visits and exchanges, we gained deeper insights into the business environment and cultural context of Middle Eastern countries. At the same time, we effectively connected with local resources, opening up more opportunities for business development and cooperation.

As an editor at XiaGuang Society who has long followed the Middle East market, I joined this journey and formed more concrete observations and clearer understandings about the real situation in the Middle East and the opportunities for Chinese enterprises going global. Despite renewed local conflicts, development and innovation remain the enduring themes of today and tomorrow in the Middle East.

UAE: The Model Nation Accelerates Digital Transformation

The first stop of XiaGuang Society’s Middle East delegation was Abu Dhabi, the capital of the UAE.

Composed of seven emirates—Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Fujairah, Umm Al-Quwain, Ajman, and Ras Al-Khaimah—the United Arab Emirates is undoubtedly a model nation in the Middle East. Public opinion surveys show that for 11 consecutive years, Arab youth have ranked the UAE as their most desired country to live in and emulate, surpassing the United States, Canada, France, and Germany.

Indeed, the UAE’s success has paved a proven path for the Arab world: achieving self-development by integrating into the global economic and trade system while preserving national cultural traditions and religious values.

In Abu Dhabi and Dubai, I constantly experienced a sense of cultural juxtaposition.

In hotels, office buildings, and even shopping malls, you can see portraits of the UAE’s founding president, current president, and vice president兼Ruler of Dubai. The last time I felt such omnipresent monarchical authority was in Thailand during the state mourning period following the passing of King Bhumibol Adulyadej, when tributes played in subway stations and royal family images were printed on T-shirts sold in malls.

Presidential portraits visible everywhere in the UAE

These details all convey one fact—that the UAE is a nation developed under authoritarian governance and strongman rule.

Of course, many other Middle Eastern countries hope to replicate the Dubai model, as it aligns well with their own political and cultural soil.

Abu Dhabi: When the Oil Capital Steps Out of the Shadows

As the capital of the UAE, Abu Dhabi may not be as internationally renowned as Dubai outside the Arab world, but it holds nearly all of the UAE’s oil and gas reserves and 87% of its land area. In 2009, Dubai suffered heavily from the global financial crisis and required a $10 billion bailout from Abu Dhabi. This funding also led to the renaming of the world’s tallest building—originally called Burj Dubai, it was renamed Burj Khalifa in honor of Abu Dhabi’s ruler and former UAE President Sheikh Khalifa (who passed away in 2022).

Burj Khalifa

According to data released by the Abu Dhabi Statistics Center on May 8, Abu Dhabi’s GDP grew by 9.3% year-on-year in 2022, making it the fastest-growing economy in the Middle East and North Africa region. Riding the wave of the digital economy, Abu Dhabi is accelerating efforts to attract innovative enterprises and foreign investment. Its competitors include not only Dubai within the UAE federation but also Saudi Arabia, which is rapidly advancing reforms.

In Abu Dhabi, we first visited the China-UAE Industrial Park located in Khalifa Industrial Zone Abu Dhabi (KIZAD). The Middle East’s current diplomatic strategy of “looking east” aligns with China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and this diplomatic honeymoon has greatly boosted industrial cooperation between the two nations.

Key areas of China-UAE industrial collaboration include new energy, machinery manufacturing, metal processing, biomedicine, fine chemicals, and petroleum equipment.

Although the Middle East lacks a complete industrial ecosystem and does not have natural advantages in manufacturing, the free trade zones offer zero tariffs and VAT, provide protection against U.S. anti-dumping and countervailing duties, and enjoy cost advantages in water, electricity, and labor. As more Chinese companies cluster here, industrial support services will continue to improve—an example of how China’s supply chain network expands into emerging markets and reaches global consumers.

Thanks to these foundations, Chinese tech firms have spotted opportunities in Abu Dhabi’s industrial upgrading. In March this year, Chinese autonomous driving company WeRide established operations at the China-UAE Industrial Park and received approval in July for a national-level autonomous driving road test license—the first of its kind in the Middle East and globally—already securing nearly 20,000 robotaxi orders locally.

XiaGuang Society’s Middle East delegation at the China-UAE Industrial Park in Abu Dhabi

During our visit to the Abu Dhabi Investment Office, officials explained that Abu Dhabi’s strength lies in serving as a regional economic hub capable of helping businesses access neighboring GCC countries. Additionally, the UAE offers a highly stable economic environment where companies can retain 100% ownership and freely transfer funds. Innovation-driven tech companies in healthcare, smart agriculture, ICT, digital infrastructure, and intelligent manufacturing also benefit from targeted subsidies and incentives.

Previously, companies targeting the Middle East market would typically enter via Dubai or Abu Dhabi before expanding into Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states—a common approach. However, competition between Saudi Arabia and the UAE to lead the Gulf economy is intensifying. In 2021, reform-driven Saudi Arabia launched its “Regional Headquarters Program,” stating that any company wishing to conduct business with the Saudi government or its affiliated institutions after 2024 should consider establishing a regional HQ in Riyadh. This policy attracted over 80 multinationals—including Deloitte, PepsiCo, and Bechtel—to relocate their regional centers to Riyadh.

To enhance competitiveness for foreign investors, Abu Dhabi has rolled out several preferential policies. First, specialized industrial parks cater to different enterprise types—for example, industrial firms are best suited for KIZAD, while fintech companies thrive in the Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM). Second, the Investment Office grants subsidies based on criteria like high-tech talent recruitment, contribution to local GDP, and whether the company serves as a regional center. Enterprises undergo quarterly KPI evaluations and can receive subsidies of up to 45% of local investment. Over 60 companies have already benefited, including two Chinese firms. Third, unlike Saudi Arabia’s adherence to Sharia law principles, English Common Law applies within Abu Dhabi’s industrial parks, supported by a neutral arbitration body that enhances corporate confidence in the legal system.

During our visits to the Abu Dhabi Investment Office and local startup incubator Hub71, I strongly sensed that the UAE is indeed a highly open nation with a vibrant entrepreneurial and innovative atmosphere. Here, you encounter professionals and aspiring founders from all over the world experimenting with cutting-edge fields.

XiaGuang Society’s Middle East delegation visiting Hub71, Abu Dhabi’s startup incubator

Dubai: Two Hot Sectors—Metaverse and New Energy

This spirit is even stronger in Dubai.

Due to limited oil reserves, Dubai was forced to diversify its economy decades earlier than other emirates. Today, this financial capital of the Middle East abounds with towering skyscrapers and eye-catching postmodern architecture. You no longer see women covered head-to-toe in black abayas—capitalist logic has replaced traditional norms.

It is also a city of stark class divisions. Each office tower houses globally oriented cosmopolitans, while South Asian workers—from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh—clean floors and serve coffee in corners. Of the UAE’s 10.17 million people, 88% are expatriates, mostly from South Asia.

David Harvey’s description of Paris comes to mind—and applies equally to Dubai: each district reveals who you are, your job, your background, and aspirations. Physical distances used to separate classes become understood as moral hierarchies, sanctified and institutionalized.

Street view of Dubai

Represented by Dubai, the Middle East has shown intense interest and enthusiasm for new concepts like the metaverse and blockchain during this digital economy wave.

In 2019, Dubai’s government launched the “Dubai Blockchain Strategy 2020,” aiming to apply blockchain across finance, real estate, supply chains, and public services. In 2022, Dubai enacted a Virtual Assets Law and established the Virtual Assets Regulatory Authority, becoming the first government agency to enter the metaverse. That same year, Dubai unveiled a five-year metaverse strategy aiming to build a “metaverse capital” and rank among the world’s top ten XR and metaverse markets.

To achieve this, Dubai is increasing R&D investment in metaverse technologies, cultivating local talent, and attracting global tech firms—including AR/VR/MR/XR, digital twin, 5G, and edge computing companies—with goals to create 40,000 metaverse-related jobs and generate $4 billion in annual economic output within five years.

Dubai even launched a “Digital Nomad Visa Program,” allowing foreign citizens earning above a certain monthly income threshold to live and work in Dubai for one to two years.

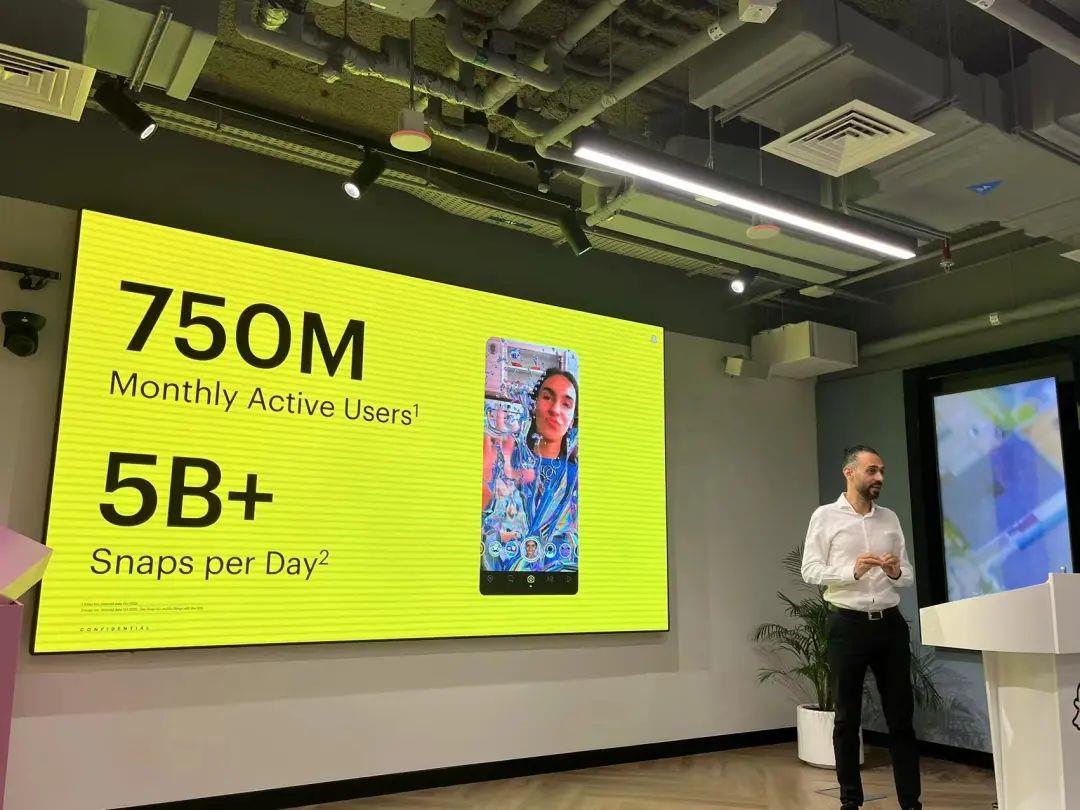

Digital entertainment applications—games, social media, livestreaming—are riding the metaverse wave deep into the Middle East, achieving full localization in capital, R&D, and operations. Snapchat rose to prominence through AR features and ephemeral messaging privacy, while many cryptocurrency firms relocated to Dubai to avoid regulatory risks.

Snapchat is a popular social app in the Middle East

In terms of overseas expansion models, the Middle East is a market with extremely high localization demands. The success of Yalla, dubbed the “Tencent of the Middle East,” stems from its early commitment to localized product design, team deployment, and transplanting traditional Arab cultural practices—like majlis, informal gathering spaces—into the digital realm. From “going global” to “localizing the model and then globalizing,” Chinese enterprises born in the digital age are iterating their globalization strategies.

Another booming sector in the UAE is renewable energy. Perhaps sensing the risks of oil dependency, Middle Eastern nations are proactively pursuing energy transitions. The UAE will host this year’s COP28 climate summit, aiming to play dual roles as both an oil exporter and green energy leader. Leveraging technological and product advantages, Chinese new-energy automakers are accelerating their entry into the Middle East market. In June, NIO signed a share subscription agreement with an Abu Dhabi investment firm; Emirati conglomerate Magna Group has also announced partnerships with Xiling Power and BAIC Blue Valley.

Next time you hear of a Middle Eastern consortium investing in a Chinese carmaker, don’t be surprised.

XiaGuang Society’s delegation at Abu Dhabi Investment Office

Indeed, the UAE is sufficiently open and dynamic, with a mature business environment. But its inherent limitation is its small market size—only about 1 million of its 10+ million population are local citizens with significant purchasing power. Neighboring Saudi Arabia is now attempting to replicate Dubai’s rise, with its capital Riyadh competing directly with Dubai for status as a regional commercial and talent hub.

Can Saudi Arabia truly rival the UAE? On day four, XiaGuang Society’s delegation flew from Dubai to Riyadh to witness firsthand what changes have occurred in this nation.

Saudi Arabia: Reform and Opening-Up Bring Century-Defining Changes

Before departure, I applied online for a Saudi visa. The moment I submitted the application, upon refreshing the page, it showed “Visa Granted.”

I was stunned. Until September 2019, Saudi Arabia remained one of the world’s most secluded nations. For decades, visas were only available to foreign laborers, business travelers, and pilgrims visiting holy sites like Mecca, with complex procedures and long processing times. Starting September 28, 2019, Saudi Arabia officially opened tourist visa applications to citizens of 49 countries—including China—launching an ambitious vision to attract 100 million tourists annually by 2030, accounting for 10% of national GDP.

The instant visa approval demonstrates this once-isolated nation’s sincerity and determination to reveal its true face to the world.

Street view of Riyadh

Saudi Arabia’s grand transformation was envisioned eight years ago. Between 2014 and 2016, global oil prices declined consecutively, compounded by the global shift toward sustainable energy, forcing Saudi Arabia to act. In April 2016, Saudi Arabia announced “Vision 2030,” built around three pillars—“Vibrant Society,” “Prosperous Economy,” and “Ambitious Nation”—setting forth a 15-year development blueprint. This sweeping change is widely regarded as Saudi Arabia’s version of “reform and opening-up.”

Transformation One: Advancing Women’s Rights, Unlocking Economic Vitality

Upon arriving in Riyadh, despite mental preparation, seeing female customs officers fully covered in black abayas with only slits for eyes still delivered a strong cultural shock.

Women in black abayas in Riyadh

The full-body black abaya reflects fundamentalist Islamic dress codes for women. As early as 1928, Lebanese Muslim scholar Nazira Zayn al-Din boldly argued in her book *Unveiling and Veiling* that removing the veil does not compromise faith. She described Lebanon as being covered by four layers of veils—one over women’s bodies, one over intellect, one over conscience, and one over progress.

For Saudi Arabia, committed to societal transformation, secularization is a key goal for this theocratic monarchy. Expanding women’s rights is central to advancing secularization. In March 2018, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman publicly stated that there is no legal requirement for Muslim women to wear abayas or face coverings. That same year, Saudi Arabia allowed women to drive and attend sports events in stadiums. In August 2019, a new royal decree granted adult women the right to travel and apply for passports without male guardian consent. It also gave women rights to register marriages, divorces, and births independently.

Saudi Arabia’s foundational “Vision 2030” explicitly aims to increase female workforce participation, raising the share of working women from 22% in 2017 to 30% by 2030. This target was surpassed ahead of schedule—in Q1 2023, female employment reached 31%.

Liberating women means liberating the nation’s vitality.

Saudi women working at a gaming expo

While most local women in Riyadh still wear ankle-length black abayas, they are increasingly visible in public life. Female sales staff and receptionists are common in malls and hotels. At Ignite, a local gaming expo, female game designers confidently present their visions of the global market to rooms full of men. At historic Diriyah Gate, now a tourist destination, groups of women laugh and chat together without husbands.

Even more surreal scenes: women in full abayas playing e-sports, enjoying indoor amusement parks, trying VR/AR wearable devices. These moments vividly illustrate that Saudi Arabia’s conservative ideology is evolving into a more flexible and inclusive form of moderate Islam.

As more economically independent women emerge, new growth potential will unfold in sectors like gaming, social media, and e-commerce in the Middle East. According to data from Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, 48% of gamers in the country are women. With government support, dedicated competitive tournaments for female players have been organized to empower them and create employment. At the gaming expo, I even saw dress-up games similar to *Miracle Nikki*, presenting clear opportunities for Chinese game developers.

A Saudi woman experiencing VR equipment

Transformation Two: Even Saudi “Rich Kids” Are Now Grinding

Another aspect of Saudi secularization is promoting national employment. Before reforms, Saudi Arabia operated as a “rentier state,” relying heavily on oil-based rents for national revenue. Externally, it exported oil to secure U.S. political and military protection; internally, it distributed oil revenues as welfare, creating an implicit contract—citizens refrain from political participation in exchange for benefits—ensuring prolonged rule by the Al Saud dynasty founded by Ibn Saud.

Historically, Saudis rarely worked. Citizens were accustomed to high subsidies and comfortable lives, with generally low education levels and weak innovation capacity. Many never worked, surviving solely on state handouts. Since the 1970s, Saudi Arabia imported large numbers of foreign laborers to fill jobs. Regulations required each foreign worker to have a Saudi sponsor, allowing ordinary Saudis to earn passive income without employment.

According to Saudi statistics, only 24% of employed individuals were nationals in 2019. UN Human Development Report data shows Saudi Arabia’s innovation index stood at 33.4 in 2022, lagging behind peers with similar per capita income, indicating developmental delays. Hence, Saudis became stereotyped as wealthy, idle “rich kids.”

On March 14, 2021, Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development officially abolished the decades-old foreign worker sponsorship system. Current labor laws mandate specific quotas of Saudi nationals across industries—known as the “Saudization rate.” Companies failing to comply face penalties, including exclusion from government contracts and loans, or suspension of foreign employees’ visas and work permits.

However, Saudization rates vary by sector. In finance, the rate is as high as 85%—meaning nine out of ten employees must be Saudi nationals. In logistics, however, the requirement is only 10%, with most labor-intensive roles still filled by expatriates.

Driven by these policies, increasing numbers of Saudi nationals now occupy service-sector positions. In contrast, service workers in Abu Dhabi and Dubai are almost entirely South Asian. From my observation, taxi drivers in Riyadh are mostly Pakistani, whereas Uber drivers booked via app tend to be locals. Pakistani drivers are often talkative and friendly, emphasizing “We are friends” with Chinese passengers; local drivers are quieter, less fluent in English, often silent or chatting in Arabic with friends via voice call—perhaps still adjusting to such rapid societal shifts.

Local Uber driver encountered in Riyadh

Transformation Three: Rigid Ideologies Are Loosening

The most visible sign of secularization is changing urban landscapes and lifestyles. Today, Riyadh resembles one giant construction site—every few kilometers reveals another building zone, with increasingly striking structures reminiscent of Dubai.

At Riyadh’s Times Square—modeled after New York—you’ll find dazzling lights and bustling crowds late into the night, DJs fusing electronic beats with Islamic music. Though alcohol-free, the energy remains electric. At Riyadh Park Mall, a central shopping destination, lights blaze at 2 a.m.—something unthinkable years ago, when much of the mall was off-limits to foreigners.

Gaming arcades seem to be everywhere.

Arcades and gaming machines populate malls and pedestrian streets. “Making Saudi Arabia a global hub for gaming and esports by 2030” is a strategic goal explicitly stated in Vision 2030.

Ironically, just a few years ago, Saudi Arabia’s Islamic gaming regulators banned many video games outright.

Women experiencing e-sports games

Riyadh is becoming a lively, human-centered city.

Young people on the street greet us warmly with “Ni hao”; food courts and snack streets offer fusion dishes blending Middle Eastern flavors with global cuisines; Kyoto’s trendy %Arabica coffee chain has opened an Instagrammable outlet where young women gather with friends.

“Riyadh will become the Middle East’s commercial and cultural center and a rising star in the Gulf, doubling its population and attracting more companies to relocate their regional headquarters here.” —Such is the ambition Saudi Arabia places on Riyadh in Vision 2030.

%Arabica, the trendy Kyoto-based coffee chain, opens a physical store in Riyadh

During our stay in Riyadh, a minor incident occurred. Before entering Times Square, men and women underwent separate security checks. Wearing a knee-length dress, I was told by a female officer that it was too short for public wear. Flustered, I argued briefly, then considered asking a friend to buy me a longer skirt from H&M across the street. Unexpectedly, the officer relented, letting me pass and even shaking my hand with a smile—as if her earlier sternness had been a joke.

This episode exemplifies how Saudi Arabia’s social rules are no longer rigidly enforced. Some previously solid boundaries are softening, though individual freedom still requires negotiation. Sometimes, this negotiation proves surprisingly easy.

A New Middle East Is Rising

Another facet of Saudi reform is reducing reliance on oil exports as the sole economic pillar, advancing privatization, and leveraging sovereign wealth funds to drive economic diversification. From sports and gaming to digital economy and renewable energy, the Saudi government is placing strategic bets to accelerate transformation.

In Riyadh, we visited Alibaba Cloud, J&T Express, and eWTP Capital, which has received investments from Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF).

Alibaba Cloud and eWTP Capital are both headquartered in King Abdullah Financial District (KAFD), downtown Riyadh. Towering skyscrapers surround you, creating a sensation akin to being back in Dubai just two days prior.

An Alibaba Cloud executive shared that office space in Riyadh is now extremely scarce—rents have tripled in two years—and hotels are fully booked. Foreign investors and entrepreneurs continuously flood in to explore opportunities, creating a fervent atmosphere of modernization and digital transformation.

Street view of Riyadh

Through field visits and discussions, I realized that although Saudi Arabia represents a massive emerging market with abundant opportunities due to its openness, it remains challenging and high-barrier. Only enterprises with mature commercial models and strong localization capabilities can truly take root.

Huang Shuozi, managing partner at eWTP Capital, noted that Saudi Arabia is a classic B2B and B2G market—many Chinese exporters’ primary clients are local governments, SOEs, and banks. Lacking domestic talent and industrial foundations, existing business environments are heavily influenced by Western firms. Commercial rules and habits differ significantly from China. Locals traditionally pay premium prices for top-tier global solutions. New systems for foreign companies only emerged after market liberalization, requiring substantial time investment.

For Chinese companies eyeing Saudi Arabia, it’s crucial to recognize they lack the first-mover advantage enjoyed by Western firms operating there for decades. Therefore, identifying market entry points is essential. After extensive frontline research, eWTP Capital identified three key B2B/B2G sectors where Chinese firms hold comparative advantages: digital economy and smart manufacturing, new energy, and digital infrastructure and consumer supply chain solutions. For instance, Alibaba Cloud provides digital infrastructure, while J&T Express advances logistics digitization—both quickly gaining solid footholds after entering the market.

XiaGuang Society’s delegation visiting eWTP Capital

Nonetheless, the Saudi market remains relatively closed, with high barriers related to sociocultural adaptation and policy alignment.

Today’s Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was founded in 1932 by Ibn Saud as an absolute monarchy, historically reliant on pilgrimage and nomadic pastoralism, still operating under tribal-style, relationship-based logic. Local connections remain the fastest and most effective way to establish presence and advance business. For Chinese firms, forming joint ventures with local partners is the primary route into this market.

Alibaba Cloud exemplifies this. In June 2022, it partnered with Saudi Telecom Company (STC), eWTP Capital, Saudi AI Company, and Saudi Information Technology Company to form Saudi Cloud Computing Company (SCCC), delivering high-performance public cloud services. According to Gartner’s authoritative assessment, Alibaba Cloud scored highest globally in IaaS infrastructure across computing, storage, networking, and security, outperforming Microsoft and Amazon. Yet, in terms of global market share, Chinese cloud providers still trail their Western counterparts.

In terms of overseas trends, cloud providers like Alibaba Cloud have evolved from merely supporting Chinese internet companies abroad to building localized teams and offering localized services. Due to geopolitical constraints, entering Western developed markets is difficult. Instead, Southeast Asia and the Middle East have become key battlegrounds for Chinese cloud providers. Compared to relatively mature cloud ecosystems in Southeast Asia and the UAE, Saudi Arabia—only recently opening up—represents another emerging frontier for Chinese cloud expansion.

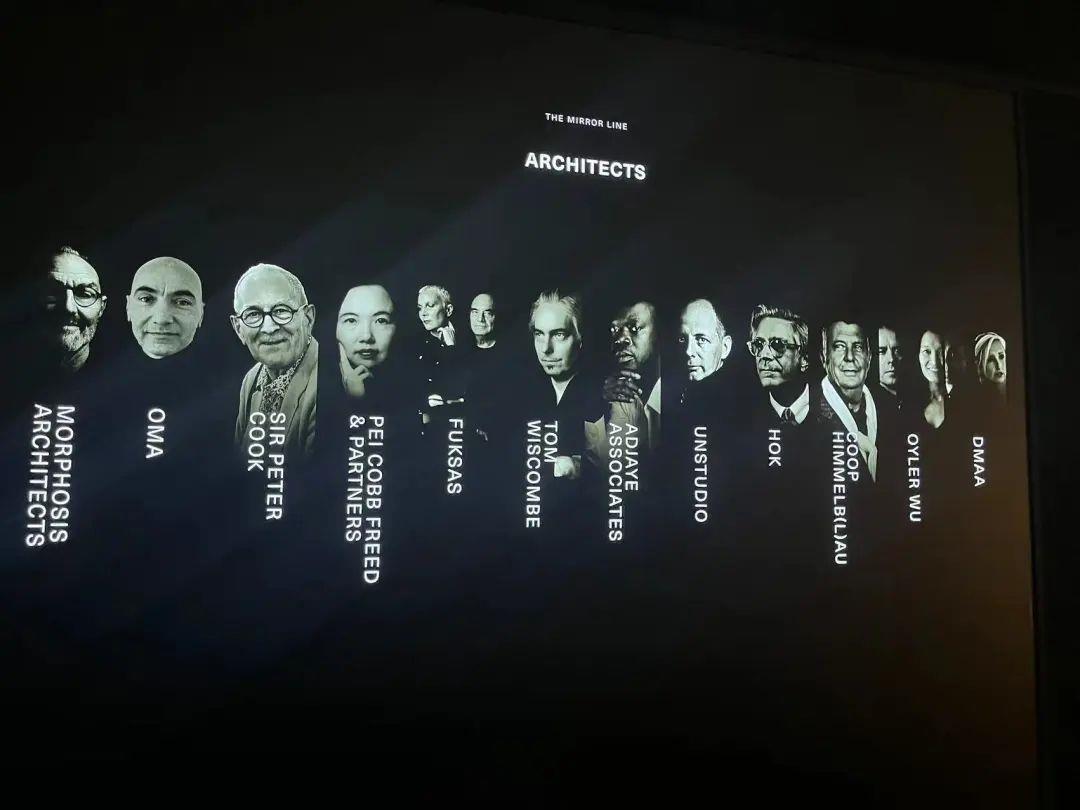

The ultimate embodiment of Saudi Arabia’s “Ambitious Nation” vision is NEOM and its centerpiece, The Line. Our delegation also visited The Line’s experience center. Upon entry, a screen played footage explaining that The Line originated from a dream of Crown Prince Salman. Indeed, it feels like science fiction made real—a linear city stretching nearly 170 kilometers, only 200 meters wide, with buildings exceeding 500 meters in height, designed to house and support around 9 million residents.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News