A Brief Analysis of the MEV Ecosystem: Profit Margins and Evolution of the Landscape Post-Ethereum Merge

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

A Brief Analysis of the MEV Ecosystem: Profit Margins and Evolution of the Landscape Post-Ethereum Merge

This article attempts to compare changes in profit margins before and after MEV, and outline the MEV lifecycle following the merge.

Author: Shisijun

Over the past year since the Ethereum Merge, MEV-Boost has maintained a market share of around 90%. This is Flashbots—a company now valued at $1 billion. Today’s MEV landscape is extremely complex, involving multiple non-user roles such as Searchers, Builders, Relayers, Validators, and Proposers. These parties engage in intricate博弈 within the 12-second block production window, all striving to maximize their individual profits.

This article aims to compare changes in MEV profitability before and after the Merge, outline the post-Merge MEV lifecycle, and share personal perspectives on cutting-edge issues.

In my previous research titled “UniswapX Protocol Interpretation,” I summarized UniswapX's operational flow and profit sources, which motivated me to fully map out the specific yield structure of MEV—after all, this is precisely what it counters and redistributes to users (essentially trading execution speed for better swap prices).

Therefore, recently I conducted an in-depth analysis of several MEV types and cross-referenced multiple data sources to calculate MEV profitability on Ethereum before and after the Merge. The full reasoning process can be found in the report: “MEV Landscape One Year After the Ethereum Merge.” Below are some selected data and conclusions:

1. MEV Profits Dropped Significantly After the Merge

-

One year before the Merge, average MEV profit was calculated at 22 MU/M using MEV-Explore data (from September 2021 to September 2022, pre-Merge), combining Arbitrage and Liquidation models;

-

One year after the Merge, average MEV profit was calculated at 8.3 MU/M using Eigenphi data (from December 2022 to end of September 2023), combining Arbitrage and Sandwich models.

The final conclusion regarding profit change is:

Based on the above statistics, after excluding hacker-related events that should not be counted as MEV, overall profitability declined sharply by 62%.

Note that MEV-Explore does not include sandwich attack data but includes liquidation revenue. Therefore, if only pure arbitrage were compared, the decline might be even greater.

Supplementary Note: Due to differences in statistical methodologies across platforms (and none including CEX arbitrage or mixed patterns), these figures serve only macro-level validation rather than absolute precision. Other reports have similarly used different data sources to compare pre- and post-Merge returns—see Appendix links.

Did the Merge cause the sharp drop in on-chain MEV revenue? To answer this, we must examine the MEV workflow before and after the Merge.

2. Traditional MEV Model

The term "MEV" can be misleading because many assume miners extract this value. In reality, most MEV on Ethereum today is captured by DeFi traders through various structured arbitrage strategies, while miners only indirectly benefit from transaction fees paid by these traders.

The classic introductory article on MEV, “Escaping the Dark Forest,” conveys the idea that there are highly intelligent hackers constantly probing smart contract vulnerabilities. However, once they discover one, they face a dilemma: how to profit without being frontrun.

After signing and broadcasting a transaction, it enters the Ethereum mempool and becomes publicly visible before being ordered and included in a block by miners. This process may take just 3 seconds or a few minutes—but within those brief moments, countless bots monitor the content of pending transactions and simulate potential outcomes.

If the hacker acts naively—simply executing the exploit—they will likely be frontrun at a higher gas price.

If the hacker is clever, they might follow the approach described in the article—using nested contracts (“internal transactions”) to obscure their ultimate profit-taking logic. Yet even then, as seen in Samczsun’s account “Escaping the Dark Forest,” success isn’t guaranteed—they were still frontrun.

This implies that MEV hunters don't just analyze parent transactions—they also scrutinize every child transaction, simulating potential profits. They even inspect gateway contract deployment logic and replicate it—all automatically completed within seconds.

The dark forest is darker than you think

When testing BSC nodes previously, I discovered numerous isolated nodes willing only to accept P2P connections but refusing to relay TxPool data outward. Judging from exposed IPs, these nodes appear to surround BSC’s core block-producing nodes.

Their motivation? By controlling P2P access yet withholding data, they create exclusive information-sharing channels among whitelisted peers—effectively monetizing resource scale to boost MEV profitability. Since BSC produces blocks every 3 seconds, the later ordinary players see transaction information, the longer it takes them to devise viable MEV strategies. Moreover, when regular players submit MEV transactions for inclusion, due to BSC’s super-node architecture, their latency is inherently higher than top-tier MEV operators physically surrounding key BSC nodes.

Beyond encircling super-nodes, exchange servers are similarly surrounded. The arbitrage margin between CeFi and DeFi is even larger, with exchanges themselves often acting as the largest arbitrage bots. This resembles early Web2 scalping scenarios, where gray-market actors would camp near servers and use DoS attacks to suppress normal user activity.

In summary, although traditional trading already involves hidden competition akin to a dark forest, the profit model remains relatively clear. After the Ethereum Merge, however, the increasingly complex system architecture quickly disrupted traditional MEV dynamics, amplifying centralization effects.

3. Post-Merge MEV Model

The Ethereum Merge refers to its upgrade from PoW to PoS consensus. The final implementation prioritized minimal disruption—reusing existing Ethereum infrastructure while isolating the consensus module responsible for block proposal decisions.

Under PoS, each block is produced every 12 seconds consistently, replacing the prior variable interval. Block rewards decreased by approximately 90%, dropping from 2 ETH to 0.22 ETH.

These changes significantly impact MEV in two ways:

1. Ethereum block intervals became stable—no longer fluctuating randomly between 3–30 seconds. For MEV, this brings both advantages and disadvantages. On one hand, Searchers no longer need to rush marginal-profit transactions; instead, they can accumulate better transaction bundles to submit right before block production. On the other hand, this intensifies competition among Searchers.

2. Reduced miner incentives make validators more inclined to accept MEV transaction auctions. Within just 2–3 months, MEV adoption reached 90% market penetration.

3.1 Lifecycle of a Transaction After the Merge

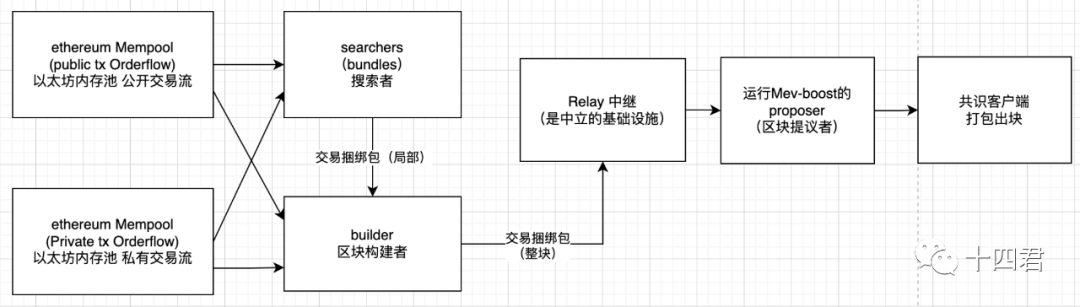

Post-Merge, the ecosystem involves five key roles: Searcher, Builder, Relay, Proposer, and Validator. The latter two are native to the PoS system, while the first three belong to MEV-Boost, enabling separation between block construction duties and transaction ordering.

-

Searcher: Scours the mempool for profitable opportunities, compiles transactions into optimized bundles (partial sequences), and submits them to Builders.

-

Builder: Aggregates bundles from various Searchers, selects the most profitable ones, possibly combining multiple bundles or reconstructing new sequences independently.

-

Relay: A neutral intermediary that validates bundle integrity, recalculates profitability, and presents several candidate block proposals for validators to choose from.

-

Proposer and Validator: Function as the post-Merge equivalent of miners. They select the highest-bidding transaction sequence from Relays to finalize the block, earning both consensus rewards (block subsidy) and execution rewards (MEV + tips).

"Block Production Process After the Ethereum Merge" – Self-created

Collectively, the lifecycle of each block now follows these steps:

-

Builders create a block by receiving transactions from users, Searchers, or other (private or public) order flows;

-

Builders submit the proposed block to Relays (multiple Builders may compete simultaneously);

-

Relays verify block validity and compute the payment amount owed to the proposer;

-

Relays send the transaction bundle and bid price (i.e., auction offer) to the current slot’s proposer;

-

The proposer evaluates all received bids and selects the most profitable bundle;

-

The proposer sends back a signed header confirming acceptance (completing the auction);

-

After block publication, rewards are distributed via on-chain transactions—shared between Builders and Proposers according to the protocol.

4. Summary

1) What impact did the Merge have on the MEV ecosystem?

By comparing profitability data and analyzing the evolution of MEV extraction workflows before and after the Merge, it’s evident that the rise of MEV-Boost fundamentally reshaped the transaction lifecycle. It introduced finer-grained roles, creating new layers of博弈. Searchers lacking cutting-edge strategies earn nothing, while those excelling can gradually expand profits and evolve into Builders.

Beyond declining on-chain volume, Searchers and Builders remain in intense internal competition—interchangeable under the system architecture. Ultimately, whoever controls order flow dominates. Searchers aiming to increase margins require large private order volumes (to build high-profit blocks), eventually transitioning into Builder roles.

For example, during the Curve attack caused by a compiler bug that bypassed reentrancy protection, a single transaction carried a fee of 570 ETH—the second-highest MEV fee in Ethereum history—illustrating the fierce competitive landscape.

Although MEV wasn’t a problem the Merge aimed to solve directly, the increased systemic博弈 combined with environmental factors ultimately reduced overall MEV profit margins. This doesn’t mean total MEV value dropped—it means more revenue flowed to validators. From a user perspective, this is positive: lower profits reduce incentives for certain on-chain attacks.

2) What are the latest frontiers in MEV research?

-

Privacy-Preserving Transactions: Approaches include Threshold Encryption, Delayed Encryption, and SGX-based enclaves—essentially encrypting transaction content with decryption conditions based on time locks, multi-signature schemes, or trusted hardware.

-

Fairness-Oriented Solutions: Include Fair Sequencing Services (FSS), MEV Auctions (MEVA), MEV-Share, and MEV-Blocker. These vary from eliminating profits entirely to sharing or balancing them—allowing users to decide how much cost they’re willing to pay for relative fairness.

-

Protocol-level enhancement of PBS: Currently, PBS exists as an Ethereum Foundation proposal implemented via MEV-Boost. In the future, this core mechanism may become natively integrated into the Ethereum protocol.

3) Is Ethereum resistant to OFAC censorship?

As the crypto industry matures, regulation is inevitable. All entities registered in the U.S. operating Ethereum PoS validators must comply with OFAC requirements. However, blockchain’s decentralized nature ensures existence beyond any single jurisdiction—so long as alternative relays compliant with local regulations exist, censored transactions can still propagate given sufficient time.

Even if over 90% of Validators censor transactions routed through sanctioned relays, anti-censorship transactions can still get confirmed within an hour. As long as it’s not 100%, it’s effectively 0%.

4) Are incentivized-less Relays sustainable?

Currently, this is an invisible issue. Maintaining complex relay services without profit risks shifting toward strong centralization. Recently, Blocknative ceased its MEV-Boost relay operations—meaning over 90% of Ethereum blocks could soon be controlled by just four companies. Presently, MEV-Boost relays bear 100% risk for 0% return. Since relays aggregate transaction bundles from various Builders, serving as data hubs, they may eventually generate revenue through mechanisms like MEV-Share or MEV Auctions—such as accepting direct privacy transaction requests from users. Map apps once faced similar challenges—public goods that couldn’t charge subscriptions—but survived by integrating ad placements and ride-hailing pilot programs. Ultimately, traffic, users, and fairness will ensure sustainability.

5) How will ERC-4337 bundled transactions affect MEV?

There are now over 687,000 AA (account abstraction) wallets and more than 2 million UserOps—representing explosive growth compared to the historically slow adoption of CA wallets. ERC-4337 features a complex mechanism, particularly in transaction signature propagation, which does not rely on Ethereum’s native mempool. While this initially increases MEV complexity, long-term adoption appears unstoppable.

For further reading, refer to our earlier report: “Latest Research Report on Account Abstraction Standard ERC-4337”

6) Can DeFi catch up with CeFi amid MEV threats?

Many current solutions aim to improve DeFi UX—such as meta-transactions, cross-chain swaps, or ERC-4337—to remove the requirement of holding gas tokens for transaction execution. Additionally, customizable contract wallet features enhance security (tiered permissions, social recovery). In my view, no matter how much DeFi improves, CeFi retains unique, unmatched advantages in speed and experience. Conversely, DeFi offers distinct strengths CeFi cannot replicate. Each serves different user bases and development cycles.

7) What is the current state of MEV in Layer-2s?

Optimism features a unique component called the Sequencer, which generates signed receipts guaranteeing transaction execution and ordering. A set of verifiers monitors the Sequencer and holds slashing authority. Optimism employs MEVA (MEV Auction), selecting a single Sequencer via auction.

Arbitrum uses Chainlink’s FSS (Fair Sequencing Service) to determine transaction order.

These approaches leverage L2-specific architectures to eliminate miner-extracted MEV to some extent. However, sidechains not interoperable with Ethereum mainnet still present MEV opportunities—such as BSC and BASE.

Finally, this article represents only 1/3 of the full analysis. For complete data and detailed reasoning, please refer to the full report: “A 10,000-Word Research Report on the MEV Landscape One Year After the Ethereum Merge: How Is the Beneficiary Chain Evolving Amid High-Complexity博弈?”

Appendix

https://github.com/flashbots/mev-research/blob/main/resources.md

https://web3caff.com/zh/archives/60550

https://web3caff.com/zh/archives/61086

https://collective.flashbots.net/t/merge-anniversary-a-year-in-review/2400

https://hackmd.io/@flashbots/mev-in-eth2

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News