The Agony of DeFi Regulation: Uniswap in Heaven, Tornado Cash in Hell

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Agony of DeFi Regulation: Uniswap in Heaven, Tornado Cash in Hell

Technology itself is innocent; the guilt lies with the people who use technological tools.

Author: Will Awang

On August 29, 2023, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York (SDNY) dismissed a class-action lawsuit against Uniswap, in which plaintiffs alleged that Uniswap allowed fraudulent tokens to be issued and traded on its protocol, causing investor losses and seeking damages. The judge ruled that the current cryptocurrency regulatory framework does not support the plaintiffs’ claims, and Uniswap bears no responsibility for harms caused by third-party use of the protocol.

Before Uniswap’s “victory,” also in SDNY, U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and other regulators filed criminal charges against Tornado Cash founders Roman Storm and Roman Semenov, accusing them of conspiring to launder money, violating sanctions, and operating an unlicensed money transmitting business during Tornado Cash’s operation. The two now face at least 20 years in prison.

Both are blockchain-based smart contract protocols—why such divergent regulatory treatment between Uniswap and Tornado Cash? This article dives into these two DeFi cases to analyze the underlying logic behind their contrasting regulatory outcomes.

TL;DR

-

Technology itself is not guilty—the guilt lies with those who misuse technological tools;

-

The Uniswap ruling benefits DeFi by establishing that DEXs are not liable for user losses arising from third-party-issued tokens—a precedent with broader implications than even the Ripple case;

-

Judge Katherine Polk Failla, who also presides over SEC v. Coinbase, stated regarding crypto asset classification: “This is not for courts to decide, but for Congress,” and affirmed ETH as a crypto commodity—could this interpretation carry over to the SEC v. Coinbase case?

-

Although Tornado Cash was also targeted due to third-party misuse, the severity stems from the founders knowingly controlling the protocol to facilitate cybercriminals, thereby infringing on national security interests;

-

Uniswap's establishment in the U.S., proactive regulatory cooperation, and its token’s sole governance function offer a model for other DeFi projects navigating regulation.

I. Investors Sue Uniswap Over Fraudulent Token Investments

In April 2022, a group of investors sued Uniswap’s developers and backers—Uniswap Labs, founder Hayden Adams, and investment firms Paradigm, Andreessen Horowitz, and Union Square Ventures—alleging they violated U.S. federal securities laws by listing "fraudulent tokens" without registration, resulting in investor harm and demanding compensation.

Presiding Judge Katherine Polk Failla noted that the real defendants should have been the issuers of the fraudulent tokens, not Uniswap’s developers or investors. Due to the protocol’s decentralized nature, the identities of the fraudulent token issuers were unknown to both plaintiffs and defendants alike. Plaintiffs thus attempted to sue accessible parties, hoping the court would extend liability onto them. Their argument centered on the claim that defendants enabled the issuance and trading of fraudulent tokens in exchange for transaction fees.

Additionally, plaintiffs stepped into the shoes of SEC Chair Gary Gensler, arguing that (1) tokens listed on Uniswap were unregistered securities, and (2) as a decentralized exchange trading tokenized securities, Uniswap should register as a securities exchange or broker-dealer with regulators. The court rejected extending securities law to cover the conduct alleged, concluding that investor concerns “are better addressed to Congress than to this Court,” citing lack of applicable regulatory authority.

Ultimately, the judge determined that existing crypto regulations do not support the plaintiffs’ claims, and under current U.S. securities law, Uniswap’s developers and investors are not liable for harms caused by third-party use of the protocol, leading to dismissal of the lawsuit.

II. Key Controversies in the Uniswap Case

Judge Katherine Polk Failla, who also oversees SEC v. Coinbase, brings substantial experience in crypto-related litigation. Reviewing the 51-page ruling reveals her deep understanding of the crypto industry.

The core issues in this case were: (1) whether Uniswap should bear responsibility for third-party use of the protocol; and (2) who should be held accountable for harms caused through protocol usage.

2.1 The underlying Uniswap protocol must be distinguished from token-specific contracts created by issuers—the actual wrongdoers (issuers) should bear responsibility

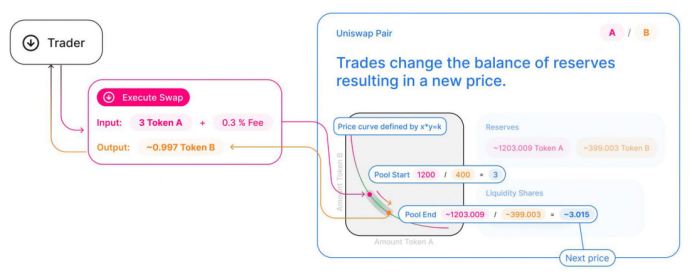

Uniswap Labs previously explained: “Uniswap V3’s concentrated liquidity pool model consists entirely of underlying smart contracts that execute automatically. Its openness, permissionless access, and inclusivity enable exponential ecosystem growth. This base-layer protocol eliminates traditional intermediaries and allows users to interact with it seamlessly via various methods (e.g., through the Uniswap Labs-developed dApp).”

Token issuers leverage this base-layer Uniswap protocol, utilizing the DEX’s unique AMM mechanism to anonymously list tokens without identity verification or background checks, creating their own liquidity pools (e.g., pairing their ERC-20 token with ETH) for public trading.

Uniswap’s decentralized nature means it cannot control which tokens are listed or who interacts with them. The judge emphasized: “These foundational smart contracts differ from the issuer-created token or pair contracts specific to each liquidity pool. The contracts relevant to plaintiffs’ claims are not the base-layer protocols provided by defendants, but rather the pair or token contracts drafted by the issuers themselves.”

To clarify, the judge offered analogies: “It would be like holding autonomous vehicle manufacturers liable when third parties use their cars to commit bank robberies or traffic violations, regardless of fault.” She compared it further to payment apps Venmo and Zelle: “Plaintiffs’ argument is akin to trying to hold these platforms liable instead of drug traffickers who used them to transfer illicit funds.”

In such cases, liability should fall on individuals committing harmful acts—not on software developers.

2.2 First Judicial Ruling in the Context of Decentralized Smart Contracts

The judge acknowledged the absence of prior legal precedents involving DeFi protocols and noted no court has previously ruled on liability within the context of decentralized smart contracts, nor found a path to hold defendants liable under securities law.

She concluded that the smart contracts powering Uniswap can operate lawfully—just as they facilitate trades of crypto commodities like ETH and BTC (“the smart contracts here were themselves able to be carried out lawfully, as with the exchange of crypto commodities ETH and Bitcoin”).

Notably, the judge explicitly referenced ETH’s status as a commodity—even if briefly.

2.3 Investor Protection Under Securities Law

Section 12(a)(1) of the Securities Act grants investors the right to sue for damages when sellers violate Section 5 (registration requirements). However, since this hinges on whether crypto assets qualify as securities—a regulatory gray area—the judge stated: “This is not for courts to decide, but for Congress.” The court declined to extend securities law to the conduct alleged, concluding that “investor concerns are better raised with Congress than with this Court,” due to lack of regulatory basis.

2.4 Summary

While SEC Chair Gary Gensler has so far avoided labeling ETH a security, Judge Katherine Polk Failla directly referred to it as a commodity (crypto commodity) in this ruling and refused to expand securities law to cover the conduct alleged against Uniswap.

Given that Judge Failla also presides over SEC v. Coinbase, could her views—that crypto asset classification is for Congress, not courts—and her recognition of ETH as a crypto commodity—be similarly interpreted in that case?

Regardless, although laws around DeFi are still evolving, one day regulators may resolve this gray zone. For now, this Uniswap ruling sets a vital precedent for the crypto and DeFi world: decentralized exchanges (DEXs) are not liable for user losses stemming from third-party-issued tokens. This outcome carries even greater significance than the Ripple case and is highly favorable for DeFi.

III. Tornado Cash and Its Founders in Peril

Unlike Uniswap, Tornado Cash—a DeFi protocol offering coin mixing services—faces dire circumstances. On August 23, 2023, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) filed criminal charges against Tornado Cash founders Roman Storm and Roman Semenov, accusing them of conspiring to launder money, violate sanctions, and operate an unlicensed money transmitting business.

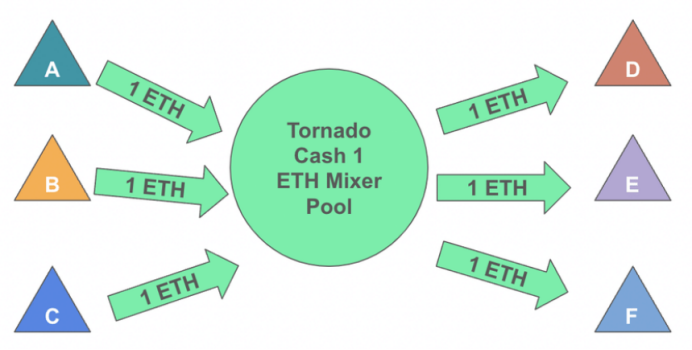

Tornado Cash was once a prominent Ethereum-based privacy tool designed to obscure the origin, destination, and counterparties of cryptocurrency transactions. On August 8, 2022, the U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned Tornado Cash, adding several associated on-chain addresses to the Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) list—making any interaction with these addresses illegal for U.S. persons or entities.

According to OFAC, since 2019, over $7 billion in illicit funds linked to ransomware, cybercrime, and darknet markets have flowed through Tornado Cash. It allegedly provided material support to malicious cyber actors worldwide, posing significant threats to U.S. national security, foreign policy, economic health, and financial stability—warranting sanctions.

3.1 Criminal Charges Against Tornado Cash and Its Two Founders

DOJ’s August 23 press release stated that the defendants and their co-conspirators developed Tornado Cash’s core functionalities, paid for critical infrastructure to promote the service, and earned millions in return. They knowingly failed to implement legally required Know Your Customer (KYC) and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) compliance measures despite awareness of illicit activity.

Between April and May 2022, Tornado Cash was used by Lazarus Group—a North Korean hacking collective under U.S. sanctions—to launder hundreds of millions in stolen crypto. Allegedly, the defendants knew these were laundering activities and modified the service to appear compliant while privately acknowledging the changes were ineffective. They continued operating the service, facilitating hundreds of millions more in illicit transfers, including moving proceeds from OFAC-blocklisted wallets.

The defendants are charged with one count of conspiracy to commit money laundering and one count of conspiracy to violate the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), each carrying up to 20 years in prison. They are also charged with conspiracy to operate an unlicensed money transmitting business, punishable by up to five years. The sentencing will be determined by the district court judge considering U.S. Sentencing Guidelines and other statutory factors.

3.2 Definition of Money Transmitting Business

Notably, FinCEN (Financial Crimes Enforcement Network), part of the U.S. Treasury, did not file civil charges against Tornado Cash or its founders for operating an unlicensed money transmitting business. If Tornado Cash falls under the definition of a money transmitter, then similar DeFi projects might too. If enforced, all such projects would need to register with FinCEN and comply with KYC/AML/CFT procedures—potentially devastating for DeFi.

FinCEN’s 2019 guidance categorized virtual currency business models to determine applicability of the money transmitter definition.

3.2.1 Anonymizing Software Provider

Peter Van Valkenburgh of Coin Center noted that the only basis for charging the defendants with unlicensed money transmission is allegedly conducting business transferring funds on behalf of the public without FinCEN registration. However, Tornado Cash functions more as an anonymizing software provider—an entity supplying tools used *in* money transmission, not performing transmission itself.

The 2019 guidance explicitly states: “An Anonymizing Software Provider is Not a Money Transmitter,” whereas an anonymizing Service Provider is.

3.2.2 Virtual Currency Wallet Provider (CVC Wallet)

Top law firm Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP published a report drawing parallels between the only business model explicitly defined as a money transmitter in the 2019 guidance—Covered Virtual Currency (CVC) Wallet providers—and the necessary criteria: Total Independent Control Over the Value Being Transmitted, which must be both necessary and sufficient.

In this case, the indictment details how the defendants controlled the Tornado Cash software/protocol, but does not establish how they controlled fund transmissions. The report analyzes Tornado Cash’s transaction flow and concludes it lacks full control akin to CVC wallet providers, as users must actively sign transactions with private keys—thus falling outside the strict definition of a money transmitter.

3.2.3 Decentralized Applications (DApps)

Gabriel Shapiro, General Counsel at Delphi Labs (@_gabrielShapir0), disagrees with Cravath’s view, arguing they overlooked another category in the 2019 guidance: Decentralized Applications (DApps).

FinCEN’s stance on DApps: “A DApp owner/operator may deploy it to perform various functions, but when a DApp performs money transmission, the money transmitter definition applies to the DApp, or its owner/operator, or both.”

The indictment relies precisely on this interpretation of DApps from the 2019 guidance to define unlicensed money transmitting activity—i.e., whenever an entity (individual, corporation, or organization) uses smart contracts/DApps to conduct money transmission, FinCEN rules apply.

If FinCEN truly intended this broad reading in 2019, why has it taken no enforcement actions against DeFi since? Given that virtually all DeFi applications involve value transfer, this interpretation could theoretically apply to every DeFi protocol.

3.3 Summary

The 2019 FinCEN guidance remains just that—a guidance. It is non-binding on DOJ and lacks legal force. Yet, amid the absence of a clear U.S. crypto regulatory framework, it remains the clearest signal of regulatory intent.

However, DOJ’s approach leaves unresolved critical questions about decentralized protocols: Should individual actors be held liable for actions taken by third parties or decisions made by loosely governed communities? U.S.-based defendant Roman Storm is set to appear in court soon for arraignment. The court may eventually have the opportunity to address these open issues.

Attorney General Merrick Garland stated: “This indictment sends a clear warning to anyone who thinks they can exploit cryptocurrency to conceal criminal activity.” FBI Director Christopher Wray added: “The FBI will continue dismantling the infrastructure cybercriminals use to profit from crime and hold accountable anyone who enables them.” This underscores regulators’ firm stance on AML/CTF enforcement.

IV. Same DeFi Protocols, Why Heaven and Hell?

Commonalities between the Uniswap and Tornado Cash cases:

(1) Both are blockchain-based smart contracts capable of autonomous operation;

(2) Both faced regulatory intervention due to third-party non-compliant or illegal use;

(3) Both raise the question: Who should bear responsibility for resulting harms?

Key differences:

In the Uniswap case, the judge found:

(1) The foundational smart contracts differ from issuer-created token contracts, and the former operate lawfully;

(2) Harm arose from issuer-created token contracts;

(3) Therefore, liability should rest with the issuers.

In contrast, the Tornado Cash indictment argues that although third-party misuse triggered regulatory action, the key distinction lies in the founders’ knowing facilitation of cybercriminals through active control of the protocol, thereby harming national security interests. In such a case, assigning liability becomes self-evident.

V. Final Thoughts

On April 6, 2023, the U.S. Treasury released the 2023 DeFi Illicit Finance Risk Assessment—the world’s first official evaluation of illicit finance risks in DeFi. The report recommends strengthening AML/CFT oversight and enhancing enforcement against crypto business activities—including DeFi services—where feasible, to improve compliance with Bank Secrecy Act obligations among crypto service providers.

U.S. regulators appear to follow this dual-track strategy: enforcing KYC/AML/CTF rules at on/off ramps to control illicit flows at source—as seen with Tornado Cash enabling money laundering—and protecting investors by regulating project-level compliance, as in CFTC v. Ooki DAO, where regulators intervened due to violations of CFTC rules, or in the Tornado Cash case, for breaching FinCEN’s money transmission regulations.

Despite the unclear U.S. crypto regulatory landscape, Uniswap’s establishment of a U.S.-based operating entity and foundation, proactive engagement with regulators, risk controls (such as blocking certain tokens), and UNI token’s exclusive governance role (avoiding securities classification disputes) collectively serve as a strong model for other DeFi projects navigating regulation.

Technology itself is not guilty—the guilt lies with those who misuse it. Both the Uniswap and Tornado Cash cases deliver the same verdict.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News