The Future of Web3 Social (1): Building Social Graphs to Solve User Acquisition

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Future of Web3 Social (1): Building Social Graphs to Solve User Acquisition

How to retain all these users and continuously generate new content (and profits)?

Written by: PAUL VERADITTAKIT, Partner at Pantera Capital

Translated by: TechFlow

This is the first article in a series on decentralized social networks written by Paul, a partner at Pantera.

The series explores how current technologies and trends are addressing a range of challenges facing decentralized social networks, offering detailed explanations and insights into each issue.

In 2017, a group of MIT Media Lab researchers claimed in Wired magazine that decentralized social networks would “never succeed.” In their article, they outlined three insurmountable challenges:

(1) The problem of attracting (and retaining) users from scratch

(2) The problem of handling user personal information

(3) The problem of user-facing advertising

They argued that in all three cases, existing tech giants like Facebook, Twitter, and Google, due to their vast economies of scale, left no room for any meaningful competition.

Fast forward to today, what was once deemed "impossible" now seems increasingly within reach. We appear to be at the dawn of a transformation in the concept of social media networks. In this three-part series (this being the first), we will explore how new ideas in decentralized social (DeSo) are solving these "old" problems, specifically:

(1) Solving the cold start problem using open social graphs

(2) Addressing user identity with proof-of-personhood and cryptographic techniques

(3) Tackling revenue through token economics and incentive mechanisms

Social Graphs and the Cold Start Problem

Social media platforms always face the cold start problem: attracting and engaging users without an existing user base or network effects. Traditionally, emerging social media startups like Snapchat, Clubhouse, or more recently Threads, have attempted to overcome this through aggressive marketing and sheer promotional power. By capturing widespread attention at the right moment—whether through novel UX design, media headlines, or FOMO—they launch massive sign-up blitzes, quickly building user barriers on their platforms. For example, Threads attracted 100 million users in just five days.

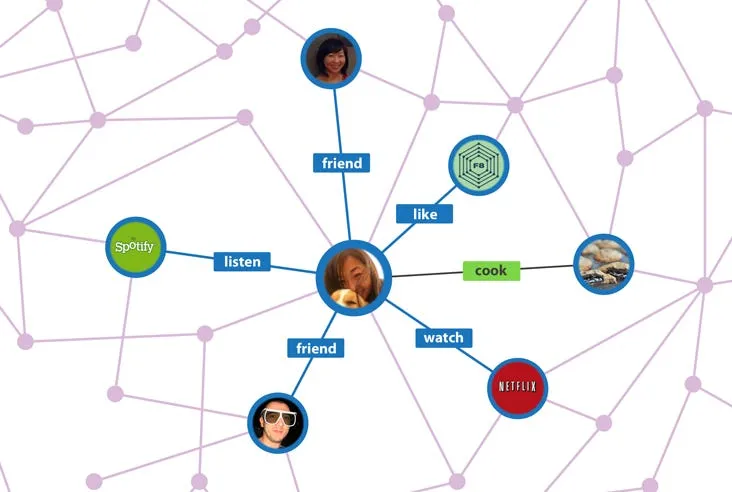

Yet these successful marketing campaigns often face an existential crisis: how to retain all these users and continuously generate new content (and profits)? This was Clubhouse’s past challenge and is currently Threads’ dilemma. As these apps fade, the valuable social graphs and user profiles built on them vanish too. Thus, future aspiring social networks must repeat difficult marketing strategies to restart their own networks from scratch.

At the heart of this lies a fundamental issue: in Web2 social networks, the social graph (mapping relationships between users) is inextricably tied to the social application itself (like Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram). These two layers are symbiotic: the novelty of the app drives growth in the social graph, while the social graph becomes the primary moat for the platform. Despite various issues, users don’t leave Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram simply because all our friends are there.

But what if we could separate the social graph from the social application? Even after Clubhouse (or Threads) disappears, we could reuse the social graph we built there to easily launch another social app. This is Web3’s answer to the cold start problem.

Using Public Blockchains as Open Social Graphs

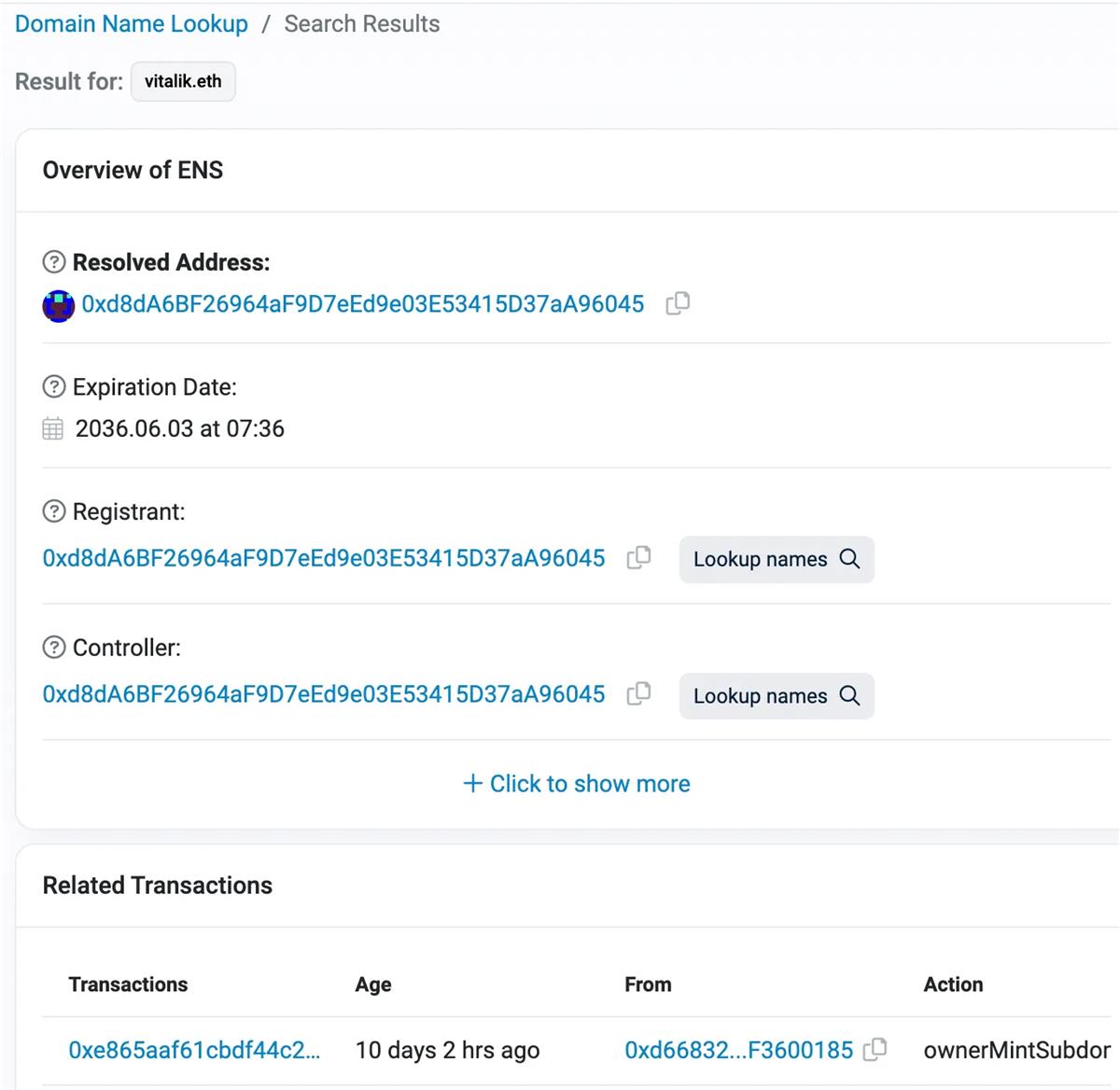

In a sense, public blockchains like Ethereum are already social graphs. If I look up an ENS domain or a person’s wallet address on Etherscan, I can view that person’s on-chain social profile: what assets they hold, who they transact with, and infer which communities they belong to.

This kind of on-chain social profile appears to be a natural starting point for a new decentralized social network, and indeed, some companies are exploring this path.

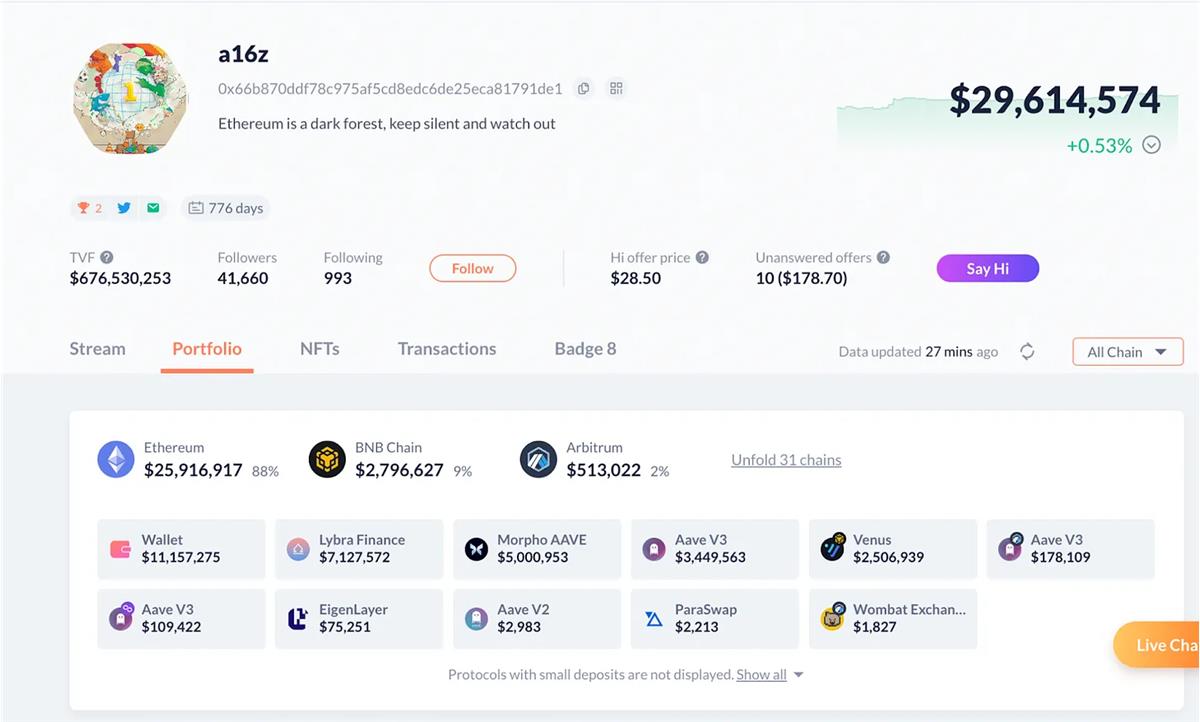

For instance, Debank transforms the hexadecimal dumps on Etherscan into readable portfolios or “profiles,” and enables messaging between these different profiles, leveraging on-chain data to bootstrap a messaging-style social network. 0xPPL takes a similar approach, attempting to use on-chain user profiles to build a Twitter-like social network. General strategies to make raw transaction data readable and interpretable for “ordinary” users—using advanced large language models such as GPT-4—are accelerating. Cymbal, for example, reportedly uses GPT to generate conversational summaries of transactions and trends, creating a hybrid of data dashboards, news feeds, and future social networks.

Building Native Social Graph Protocols

Relying solely on public blockchain data (like Ethereum) has a limitation: such data isn't rich enough for social applications. Since public blockchains were primarily built for financial applications, not social ones, the data natively collected on-chain—such as transaction history, account balances, and token holdings—isn’t necessarily the most useful for social networks.

Instead of merely using native on-chain data as a social graph, one idea is to build a new, dedicated social graph protocol atop public blockchains. For example, Lens Protocol leverages the key insight that social interactions in apps share common elements, abstracting them into distinct on-chain actions like “post,” “comment,” and “mirror” (i.e., share or retweet).

Farcaster has similar abstractions in its social graph, such as “cast” (post), “reactions” (likes), and “amp,” a feature allowing users to recommend others worth following. The main difference between Farcaster and Lens lies in their technical implementation—Lens places everything on the Polygon blockchain, while Farcaster anchors its ID registry on Ethereum itself and runs its social graph on an L2 as a delta graph.

A third notable social graph protocol is CyberConnect, which, through its Link3 mechanism, emphasizes link aggregation (including both on-chain and off-chain sources) and focuses initially on events and fan clubs as use cases.

The key point for these social graph protocols is that they don’t necessarily build top-layer social apps like Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram. Instead, they provide an open social graph layer (essentially an SDK) needed to build and scale such top-layer applications. As mentioned earlier, the core advantage is that even if a once-successful social app disappears (like Clubhouse), the generated social graph remains usable by other developers. Hence, only one successful marketing campaign or app is needed to bootstrap an entire ecosystem.

Designing Decentralized Social Media from Scratch

A third strategy is to build a decentralized solution entirely from scratch. The premise is that social media apps are foundational to our digital experience, thus requiring a dedicated blockchain (or other decentralized) solution that natively supports core social operations, rather than relying on protocols built atop infrastructure originally designed for financial use cases. In short, we need a “social app chain.”

One of the most notable projects pursuing this strategy is DeSo, which is building an L1 blockchain focused exclusively on social applications. Unlike mainstream public blockchains that prioritize “transactions per second,” DeSo optimizes for “posts per second” and the communication and storage demands of social apps—areas where general-purpose blockchains like Ethereum aren’t necessarily optimized. On top of this L1, DeSo plans to build various social apps, including long-form content (like Substack), short-form content (like Twitter), and Reddit-like platforms.

Other decentralized social media platforms, such as Bluesky and Mastodon, also broadly follow this from-scratch design philosophy. Strictly speaking, they are not blockchain-based solutions but instead rely on server systems to ensure sufficient decentralization of posts. For example, Mastodon uses an email-like system where users can choose among different service providers (like Gmail, Hotmail, or iCloud). Just as an organization can set up and customize its own mail server, each “instance” on Mastodon functions as a self-governed and customizable community. Bluesky, on the other hand, is an app built on the open-source AT Protocol—an open social graph with APIs for “follow,” “like,” and “post”—specifically optimized for Twitter-like social platforms.

What DeSo, Mastodon, Bluesky, and similar projects share is a rejection of the notion that existing public blockchain designs (represented by the EVM) are suitable for social networks. While this approach undoubtedly gives these projects finer control over design decisions and user experience, it also severs potential connections and synergies with DeFi, existing NFT communities, and other mature elements of the Web3 ecosystem. Moreover, it remains to be seen how “decentralized” these solutions truly are, especially when their decentralization isn’t guaranteed by public blockchains. Will these solutions ultimately bundle social graphs tightly with their apps like existing networks, or will they sufficiently decentralize the social graph layer to attract diverse applications and developer teams? This is a critical question for the future of Web3 social.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News