With the rise of DeFi and frequent launches of central bank digital currencies, will the U.S. dollar lose its status as the world's reserve currency?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

With the rise of DeFi and frequent launches of central bank digital currencies, will the U.S. dollar lose its status as the world's reserve currency?

The days of the dollar as a reserve currency may be numbered.

Author: BEN LILLY

Compiled by: TechFlow

Until recently, my long-term view has been firmly held: the U.S. dollar would not lose its status as the world's reserve currency.

Even after JPow got an infinite printing press and Russia and China began investing in each other with hopes of forming a competing trade bloc among BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China), I still held this view.

But a few weeks ago, I was forced to revise my assumption.

What changed my mind was applying Zoltan Poszar’s theories on monetary regime shifts to the case of cryptocurrency—specifically, what happens when new settlement technologies enter the market.

To explain this, I want to dive into some major changes currently unfolding at the global level.

The days of the dollar as the reserve currency may be numbered

You might have heard me—or others like me online—mention Bretton Woods III (BW3).

It’s a sensitive topic sparking heated debate among economists, traders, and even retail investors. It touches on one of the most important themes in finance: the global monetary order.

The legacy of Bretton Woods began in 1944. The system tied global currencies to the U.S. dollar, which in turn was backed by gold. This ensured stability and predictability, cementing the dollar’s role as the dominant global reserve currency.

Bretton Woods V1 ended in 1971 when Richard Nixon severed the dollar’s link to gold, ushering in V2.

What followed was fiat money—literally meaning “let it be done.” In other words, the “$10” printed on a dollar bill is worth $10 because we say so. It meant the dollar was no longer backed by gold but only by the official decree of those managing the printing presses.

This elevated the role of central banks, as their task of maintaining price stability became more difficult.

Since the U.S. was becoming the reserve currency provider, it needed to run massive trade deficits to allow dollars to flow into global markets. The trade relationship between the U.S. and China best illustrates this dynamic, with China holding over a trillion dollars in U.S. Treasuries for years—until recently reducing its holdings.

This also gave rise to the petrodollar. The U.S. helped oil producers by paying them in dollars, which allowed future oil buyers, banks, and others to assist these producers with trade financing. This led to the creation of entire oil markets across the Middle East.

The dollar became the medium of global trade. That’s why 88% of foreign exchange settlements involve the dollar. While it’s easy to complain about petrodollars, eurodollars, etc., this policy did solve many global trade problems (like currency valuation fluctuations, settlement issues, and acceptance).

According to interest rate expert Zoltan Poszar, formerly of the New York Fed and Credit Suisse, all this changed in 2022 when Russia invaded Ukraine.

The harsh sanctions imposed on Russia stripped it of access to much of its foreign exchange reserves, including dollar supplies. This set a precedent: if you defy U.S. policy, your assets can be seized. It marked a moment of financial warfare through the abuse of global hegemony.

This signaled the arrival of Bretton Woods V3.

Now, countries look at the dollars in their bank accounts and realize they carry new risks.

They realize that the dollar value on their balance sheets is less valuable than the commodities they can sell to the world. This suddenly emphasizes investment in commodity markets and supply chains.

That’s why we’re now seeing some trade agreements that no longer involve the dollar. This transition will take time, mainly due to the sluggishness of governments and legacy financial infrastructure.

But most interestingly, the technological infrastructure of trade is about to undergo a massive upgrade—we can explore this further before drawing conclusions...

Global regulators are experimenting with DeFi

If you browse websites of the world’s largest banking institutions—like the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) or the International Monetary Fund (IMF)—you’ll find a common theme: tokenization and digital currencies.

In short, central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) are coming fast. This means our current technology needs an upgrade.

Two notable initiatives are the Monetary Authority of Singapore’s “Project Guardian” and the BIS’s “Project Mariana.”

“Project Guardian” is based on a distributed ledger technology called the Multi-CBDC Bridge (mBridge). It’s a fancy name for swapping CBDCs. Or, for us crypto enthusiasts, it’s simply using Uniswap v2 AMM technology to swap tokens.

If you read the reports on “Project Guardian,” you’ll find lengthy explanations of how to efficiently swap tokens.

Let me say this: Wall Street is really good at making great technology incredibly boring.

Anyway, as most of us know, you can now swap assets at the tail end of liquidity curves… imagine Vietnam trading tokens directly with Costa Rica, without needing the dollar.

Another popular initiative is Project Mariana. This project involves the Monetary Authority of Singapore, the BIS, the French Central Bank, the Swiss National Bank, and others.

They call it an experiment… leveraging Curve’s AMM technology. We can clearly see how they understand how AMMs work and the advantages of certain AMMs in different use cases.

To briefly summarize Project Mariana… it enables token transfers (referred to on the network as “wCBDC”). Central banks issue and add liquidity, then commercial banks use wCBDC tokens to trade with AMMs and other banks.

Think of it as a permissioned minting contract from the central bank, allowing commercial banks to interact with AMMs.

Common terms used in these explanations include “security,” “cross-border,” and “efficiency.” There’s nothing wrong with that. But what’s missing is: what happens to the dollar as a medium of trade?

We all know AMMs enable transfers with far less reliance on the dollar—or even Ethereum. This means reduced dependency on the dollar for exchanges and transactions. In other words, the previously mentioned 88% of FX settlements involving the dollar could be at 100% risk.

The next source of inflation

I clearly remember my academic paper-writing days. Looking back, I can’t help but feel I sounded robotic.

And hard to understand. That’s why these papers shifted my thinking within days. What fascinated me was whether anyone was researching what happens if demand for the dollar declines.

It would be great if someone connected this with the new AMM technology.

But I couldn’t find anything… except two papers from the IMF.

The first is “Digital Currencies and Central Banking,” and the second is “Declining Cash Use and the Demand for Retail Central Bank Digital Currency.”

The title of the second is quite telling. These papers discuss how the shift from physical cash to digital alternatives alters the dynamics of monetary policy and inflation.

Plainly put, the authors examine CBDCs and inflation. I appreciate their approach because they consider two outcomes.

First, they note that increased use of digital banking services and non-bank alternatives to cash reduces demand for physical cash.

This shift affects the ratio between physical cash and GDP, as well as broader monetary aggregates. Without reserve requirements for e-money (physical storage of digital currency), shifting from bank deposits to e-money reduces broader monetary aggregates.

Their point is that capital controls may be needed.

Otherwise, we get the second outcome: in economies requiring proportional reserve backing, the shift from cash to e-money won’t affect broader aggregates.

All of this ties into the so-called “shadow banking” system—the part of the monetary system outside regulated money supply oversight.

This suggests these non-CBDC forms could reduce dollar usage, potentially leading to inflation.

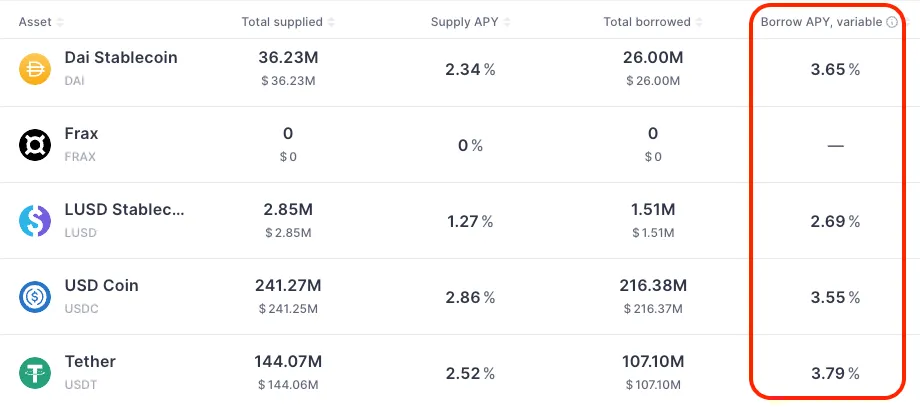

For crypto degens… if you borrow tokens via Aave using over-collateralization, this creates such possibilities…

When you go to a bank and borrow against your house at such rates…

These alternative forms of the dollar—DAI, USDC, USDT—are not printed by the Federal Reserve, which actually creates problems for the interest rate control the Fed is trying to maintain.

This leads to reduced demand for real dollars… and higher inflation.

It’s fascinating to think about. In a way, I understand why new Basel guidelines will soon emerge. These guidelines tell banks how much capital they must hold in reserve to support their operations. They address exactly the kind of issues mentioned above.

Therefore, we should expect stablecoin regulations to align with this thinking… otherwise, they’d actually undermine what the Fed is trying to achieve.

Before I receive hate mail for supporting the Fed’s regulatory stance, let me say: the dollar is theirs. Creating our own version is just replicating their invention. We have our native tokens… perhaps we should focus on building additional stability within them instead of worrying about stablecoin regulation.

But before I stray too far, I want to emphasize the key point behind raising this discussion on currency demand and inflation…

These papers do not mention the potential decline in currency demand associated with new foreign exchange settlement technologies like “Project Guardian” and “Project Mariana.” I’m curious when these institutions will address this, because I believe someone at the Fed, BIS, or IMF is already thinking about it.

This isn’t just a big problem for the U.S.—it’s global. As a catalyst, it appears to be triggering a hidden inflationary tsunami.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News