The Right Way to Analyze FDV: Don't Be Misled by Valuation Size, Consider Token Dilution Effects

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Right Way to Analyze FDV: Don't Be Misled by Valuation Size, Consider Token Dilution Effects

Fully diluted market cap makes sense to some extent.

Written by: SAM ANDREW

Compiled by: TechFlow

Fully diluted market cap, often referred to in the cryptocurrency space as FDMC or fully diluted valuation (FDV), is a concept that twists an equity market idea into a crypto context. The concept aims to capture the dilutive nature of a protocol. However, its current application is flawed and requires updating.

This article explores the fallacies behind the concept of "fully diluted market cap" in cryptocurrency and proposes an alternative approach.

Review

Market capitalization represents the equity value of a company in the public markets. It equals the company's stock price multiplied by the number of outstanding shares. The rise of tech companies in the 1990s gave birth to stock-based compensation. Companies began paying employees with stock options. Stock compensation offers several benefits: it aligns incentives between the company and employees, it’s a non-cash expense, and it enjoys favorable tax treatment.

Until recently, stock compensation did not appear on a company's income statement nor as a cash item on its cash flow statement. It was an expense that didn’t show up anywhere—yet eventually reflected in the number of outstanding shares. As the share count increased, earnings per share declined, all else being equal.

Investment analysts adjusted for this virtual stock compensation expense by modifying the outstanding share count. Analysts added future shares to be issued to employees to the current outstanding shares. The sum of these two became known as fully diluted shares. Fully diluted shares multiplied by the stock price yield the fully diluted market cap. Fully diluted shares and market cap are standard in equity investing.

Application to Cryptocurrency

A similar market cap concept applies to cryptocurrencies. A protocol’s market cap is the token price multiplied by the circulating supply of tokens. Circulating supply is roughly equivalent to outstanding shares. However, unlike a company’s relatively stable outstanding shares, a protocol’s circulating supply frequently increases significantly.

Companies generally avoid issuing new shares. Issuing shares equates to selling equity in the company at the current stock price. If a company is optimistic about its future, why sell equity today? Doing so dilutes existing shareholders.

In contrast, protocols frequently issue additional tokens. Token issuance is part of their “business model.” It all started with Bitcoin. Bitcoin miners ensure transactions are correctly recorded on the Bitcoin blockchain and are rewarded with Bitcoin. Thus, the Bitcoin network must continuously issue new bitcoins to compensate miners. Subsequent blockchains adopted the same model: issuing native tokens to reward those who accurately validate transactions.

This intrinsic token issuance model means more tokens continuously enter circulation. Standard market cap fails to capture the impact of future token issuance. Hence, the concept of fully diluted market cap emerged. Fully diluted market cap is the current token price multiplied by the total number of tokens that will ever be issued. For protocols with increasing supplies, a ten-year supply figure is often used.

Fully Diluted Market Cap Makes Some Sense

People rightly recognized that standard market cap doesn’t tell the full story. A different metric was needed to account for all future token issuance.

At the same time, a protocol’s “business model” has evolved. New token issuance is no longer just about rewarding miners, as with Bitcoin. Tokens are now also used to grow the network. Token issuance can help bootstrap a network toward functionality. A network—be it Facebook, Uber, Twitter, or a blockchain—isn’t very useful without many users. Yet few people want to be early adopters. Distributing tokens to early adopters provides financial incentives for them to use and promote the network until others join and make it inherently valuable.

Token issuance has also become a form of compensation for ambitious developers building the protocol and the venture capital funds supporting them. There’s nothing wrong with rewarding entrepreneurs, VCs, and early adopters. The point is, token issuance has become more complex.

But Fully Diluted Market Cap Has Flaws

The logic behind fully diluted market cap is deeply flawed.

1. Mathematical Error

Somehow, the crypto market believes that if a protocol issues more tokens, its value should increase. This is completely wrong. In business, economics, or even crypto, there is no example where issuing more of something makes each unit more valuable. It’s basic supply and demand. If supply increases without matching demand, the value of each unit decreases.

The FTT token is a classic example. Its token structure and mechanics were similar to other tokens. Before the FTX collapse, FTT traded at $25. Its market cap was $3.5 billion with 140 million tokens in circulation. Its fully diluted market cap was $8.5 billion with a total supply of 340 million tokens.

So, by issuing an extra 200 million tokens—increasing supply by 2.4x—the market cap of FTT supposedly increased by 2.4x... How does that make sense?

For FTT’s fully diluted market cap to truly reach $8.5 billion, the additional 200 million tokens would need to be sold to buyers at the then-current price of $25. But they weren’t. The extra 200 million tokens were simply given away, generating no revenue.

The table below illustrates the difference in FTT market cap and token price between issuing versus selling 200 million FTT tokens. Token issuance simply adds 200 million tokens to the existing supply, resulting in a fully diluted supply of 340 million. Issuance has no impact on FTT’s market cap. The expected effect is a 143% increase in total tokens and a 59% drop in price per token. It’s simple math: a constant numerator and an increasing denominator yield a smaller result.

Alternatively, if those 200 million FTT tokens were sold at $25, FTT would have raised $5 billion in revenue, increasing its market cap to $8.5 billion. Circulating supply would rise to 340 million. Both market cap and supply would increase by 143%, leaving the price per token unchanged.

Stocks work similarly. If Apple issues more shares to employees as equity compensation, it receives no cash. The result: fully diluted shares increase, and price per share drops. If Apple sells shares at market price, it gains cash, increasing its market cap accordingly. Shares outstanding increase proportionally, leaving the stock price unchanged.

Applying crypto’s fully diluted market cap logic to stocks exposes its flaw. If this logic held, every company should issue more shares to boost its fully diluted market cap. Clearly, that doesn’t happen. Taken to its logical extreme, every company’s fully diluted market cap would be infinite—since there’s no limit to how many shares a company can issue. Thus, regardless of size, growth, profitability, or returns on capital, all companies would have the same infinite fully diluted market cap. Obviously, that’s not the case.

What about deflationary protocols?

Most protocols are inflationary—issuing more tokens over time. Some are deflationary—or will become so—meaning the circulating supply will decrease. Under crypto’s fully diluted market cap logic, a deflationary protocol would be worth less in the future than today.

Something becomes scarcer over time, yet its value declines because of that scarcity. That makes no sense. It contradicts basic supply and demand economics.

2. It Implies Impossible Outcomes

Crypto’s fully diluted market cap logic implies impossible scenarios. If FTT’s fully diluted market cap was $8.5 billion while its actual market cap was $3.5 billion, the market implies that each recipient of the additional 200 million FTT tokens creates $5 of value per token upon receipt. As explained, this issuance generated no revenue. So, to reach an $8.5 billion fully diluted market cap, recipients of the 200 million tokens would need to create $5 billion in value overnight.

But how could they?

How does putting more tokens into people’s hands increase market cap? It’s impossible. These tokens likely just sit in wallets as portfolio holdings. Recipients do nothing but trade the extra tokens.

3. Unintended Consequences

An unintended consequence of crypto’s fully diluted market cap logic is overstating protocol value. Investors, rightly or wrongly, often equate higher market cap with greater value and stability. Many investors feel reassured by large fully diluted market cap valuations, unaware of the flawed logic behind the calculation. In this regard, FTT was a prime offender.

When FTT traded at $50, its market cap was $7 billion and its fully diluted market cap $17 billion. Yet during that period, FTT’s average daily trading volume rarely exceeded a few hundred million dollars.

The combination of massive fully diluted market cap, modest market cap, and tiny trading volume was a recipe for disaster. At the peak of the crypto market, some tokens followed this pattern. This setup enabled market manipulation. Low trading volumes allowed a few players to control volume and thus price. Price determines market cap, which in turn inflates fully diluted market cap. This meant artificially inflated token values—supported by little or no real trading activity—were used as collateral for loans, masking the true scale of investment.

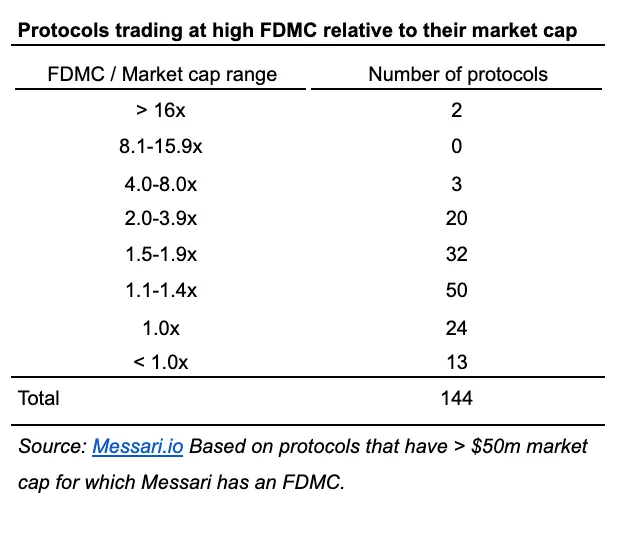

Today, assets with high fully diluted market caps and low market caps are less common—but still exist. The table below shows the number of protocols with various multiples between fully diluted market cap and market cap.

4. Token Issuance Resembles Stock-Based Compensation

Since Satoshi wrote the Bitcoin whitepaper, the purpose of token issuance has evolved significantly. Tokens are now issued for purposes beyond rewarding miners and validators.

Token issuance increasingly resembles equity compensation in traditional markets. Protocols reward those contributing to network development with their native tokens, just as companies grant stock options to employees, advisors, and investors for their contributions.

Token issuance should be viewed like stock-based compensation. Issuing tokens, like issuing shares, is a cost to the protocol or company. It dilutes the circulating supply. However, when done right, this cost is an investment—it generates returns. A diligent employee granted stock can create more value than the stock’s cost. Similarly, network participants can generate value exceeding the tokens they receive.

Returns from granted tokens take time to materialize. Until then, a thoughtful issuance plan is the best indicator of potential outcomes: excessive token distribution or severe dilution without corresponding value creation is meaningless.

Not All Token Allocations Are Equal

Fully diluted market cap calculations include all future token issuance. But not all token issuances are the same. Some tokens go to early adopters, some to founding teams, others to early investors. Some are allocated to the protocol’s foundation for future use—such as treasury reserves and ecosystem funds. These are tokens intended to develop the network. Tokens earmarked for future network investment should not be included in the circulating supply.

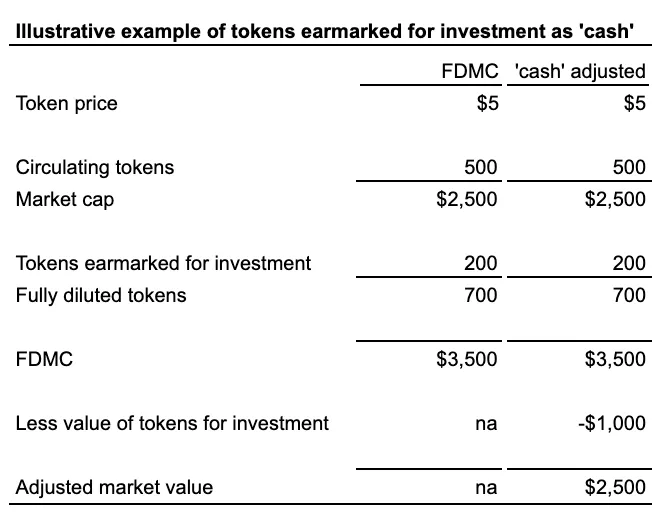

Tokens reserved for future investment are analogous to cash on a company’s balance sheet. Cash reduces a company’s total enterprise value. Enterprise value reflects the total value of all assets. Part of enterprise value is equity value—market cap for public companies. Another part is net debt (total debt minus cash). A company’s assets are funded by equity and net debt. The table below illustrates how adding cash reduces enterprise value, all else equal.

The value of tokens reserved for investment equals the token price multiplied by the designated amount. This is capital the protocol must invest—equivalent to cash on the balance sheet.

The table below outlines this logic mechanically. It shows a protocol with 500 circulating tokens. An additional 200 tokens are issued to a reserve fund, designated for network investment. At a $5 token price, market cap and fully diluted market cap are $2,500 and $3,500, respectively. The 200 reserved tokens are worth $1,000. This $1,000 should reduce the protocol’s total value, just as cash reduces enterprise value.

Tokens reserved for future investment can be seen as unissued corporate shares. Like treating them as “cash,” the conclusion is the same. Apple’s potential future shares aren’t included in its fully diluted market cap. Apple can sell shares to raise cash for product development. The future value of those products eventually reflects in Apple’s market cap. Similarly, a protocol can issue tokens to its treasury to raise “cash” for network investment. The difference is, for a protocol, “cash” is its native token. It doesn’t need to sell tokens on the market like Apple. In this sense, a protocol operates more like the Federal Reserve, issuing currency to fund operations.

The Difference Is Flexibility

Protocols start with so many tokens in circulation because their structures are rigid. Companies can freely issue and repurchase shares, subject to board and shareholder approval. In contrast, protocols find it much easier to issue and burn tokens.

From day one, protocols must define total token supply and issuance schedule—a “set it and forget it” mindset. Companies and central banks don’t operate with such rigidity. Share counts and money supply fluctuate with market dynamics. Protocols must disclose fixed token supplies because their tokens serve as monetary rewards for network participants. Uncertainty about supply would worry participants about inflation eroding their rewards. The cost of eliminating this fear is an inflexible token structure.

Inflated Fully Diluted Market Cap (FDMC)

Some protocols inflate their fully diluted market cap (FDMC). The token count used in FDMC includes tokens issued to the treasury for investment. This inflated supply leads to an inflated FDMC and, consequently, higher valuation multiples.

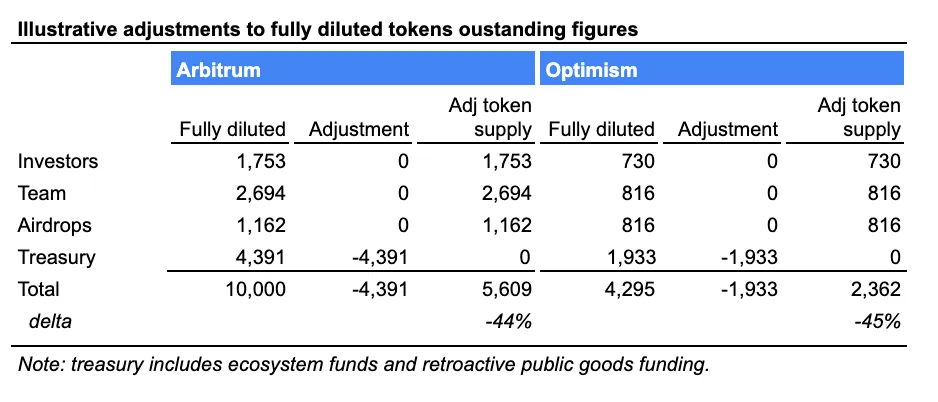

For example, Arbitrum and Optimism inflate their FDMC. Their FDMC includes the total tokens ever to be issued. Yet in both cases, large portions are allocated to treasury or equivalent bodies, designated for ecosystem investment. Removing these from total supply yields a more accurate adjusted supply and thus a more accurate market cap.

The table below shows the adjustments needed for Arbitrum and Optimism’s token supply. Adjusted supply is 45% lower than the fully diluted figure.

So What Is the Correct Token Supply?

Circulating supply is somewhat correct—it reflects currently issued tokens. But it ignores future issuance. Fully diluted supply is also somewhat correct—it accounts for all tokens to be issued. But it fails to adjust for treasury-held tokens. The corrected figure should start with fully diluted supply and subtract treasury-allocated tokens.

One thing is certain: fully diluted market cap figures are misleading. Astute analysts should not inflate a protocol’s valuation based on future token issuance, but rather discount current valuations to reflect the dilutive impact of future issuance.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News