Where is the "new moat" for AI-driven applications?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Where is the "new moat" for AI-driven applications?

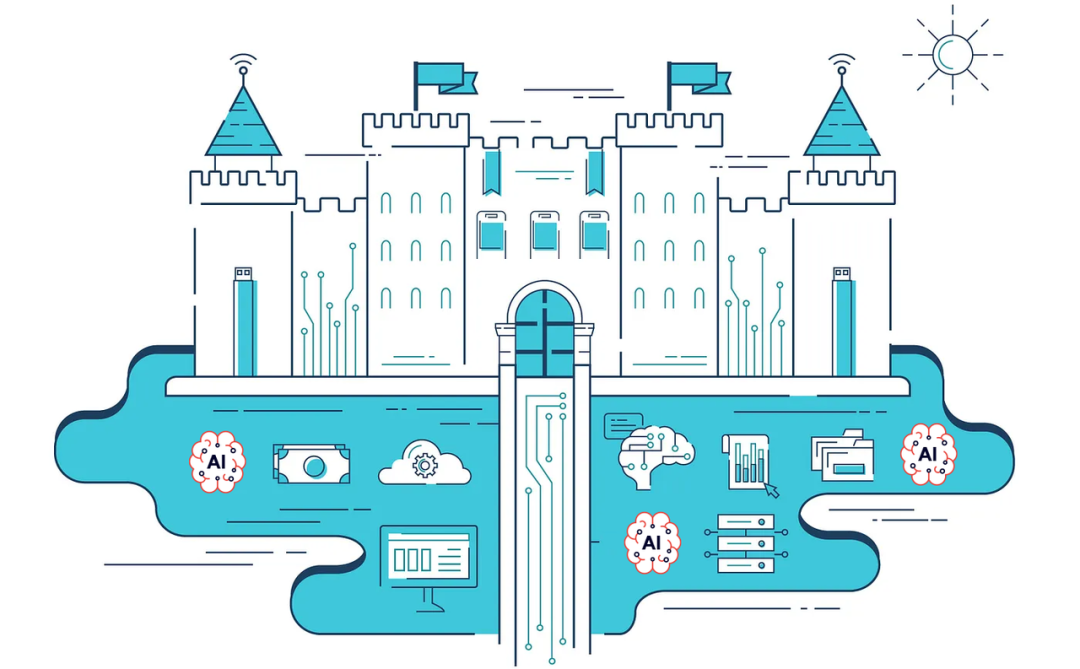

To build a sustainably profitable business, you need to establish strong defensive moats around your company.

In business, I look for economic castles protected by unbreachable moats.

— Warren Buffett

Six years ago, Jerry Chen published an article on Greylock titled "The New Moats: Why Intelligent Systems Are the Next Defensible Business Model," speculating that startups should leverage artificial intelligence to build defensive moats. Today, with more and more LLM models going open source, building proprietary large language models no longer seems to be a sustainable barrier. So what will be the moat for AI companies in the future? A few days ago, Jerry Chen revisited intelligent systems and traditional tech company moats, offering new insights into the next generation of moats in the context of widespread LLM open-sourcing.

Sense Thinking

- Traditional Business Moats: Economies of scale, network effects, deep tech/IP/industry expertise, high switching costs, and brand/customer loyalty are the traditional moats for technology companies.

- New Moats in the Gen-AI Era:

1. Foundational Model Moats: 1) The way to solve hard problems is shifting from clever product and interaction design to the model itself. Foundational models have become one of today’s deep tech/IP moats, while startups at the application layer currently lack sufficient defensibility. 2) Deep tech moats still exist—reliable business models can be built around IP—but only when addressing technical challenges with few substitutes, requiring difficult engineering and operational knowledge to scale.

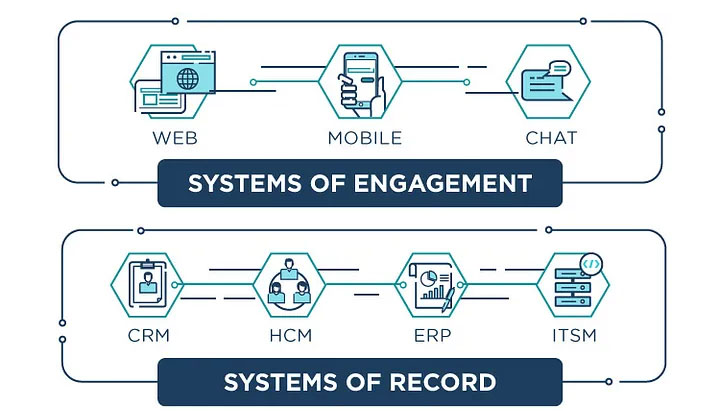

2. Intelligent System Moats: 1) Enterprise systems can be divided into “systems of record” and “systems of engagement.” Ownership of engagement systems holds the highest value. Multimodal interactions will disrupt engagement systems and impact record systems. 2) “Intelligent systems” connect and manage multiple datasets and record systems across three main domains: customer journey–centric applications, employee-facing apps (e.g., HR, ITSM, finance), and infrastructure systems (e.g., security, compute/storage/networking, monitoring/management).

- What Remains Unchanged: The value of applications lies in how value is delivered. Workflows, integration with data and other apps, brand/trust, network effects, scale, and cost efficiency remain key drivers of economic value and defensibility. AI does not change how startups market, sell, or partner—they still need to master go-to-market execution.

Introduction

To build a sustainably profitable business, you need strong defensive moats around your company. This is especially critical as we undergo the largest platform shift in a generation—applications moving to the cloud, consumed on devices like iPhone, Echo, and Tesla, built on open source, and powered by AI and data. These transformations have rendered some existing moats obsolete, making it feel nearly impossible for CEOs to build a defensible business.

The growing number of open-source models such as LLaMA, Alpaca, Vicuna, and RedPajama has led Google to admit, "We don’t have a moat, and neither does OpenAI." Proprietary advantages once held by Google and OpenAI are being disrupted by open source—especially Meta’s release of the LLaMA model, which spawned an ecosystem of developers refining and improving the base model. Google noted, “Ironically, the only clear winner from all this is Meta. Since the leaked model was theirs, they effectively gained free labor from the entire planet.”

However, Meta isn’t the only beneficiary. Startups across the market, big and small, also gain advantages. In the original 2017 article “The New Moats,” the author correctly identified the power of open source but wrongly assumed it would only benefit large cloud providers capable of massive-scale delivery. Instead, this new wave of AI models may shift power back to startups, enabling them to leverage foundational models—whether open or closed—in their products.

Indeed, some early beneficiaries of this new AI wave are existing companies and startups that have successfully integrated generative AI into their applications—such as Adobe, Abnormal, Coda, Notion, Cresta, Instabase, Harvey, EvenUp, CaseText, and Fermat.

As Darwin might say, “It is not the strongest (largest, best-funded, or most famous) that survives, but the one most adaptable to integrating AI.” This article isn’t about whether moats exist, but rather where AI value accumulates and explodes.

Historically, open-source technologies have reduced value in their own layer and shifted it to adjacent layers. For example, open-source operating systems like Linux or Android reduced app dependency on Windows and iOS, shifting more value to the application layer. This doesn’t mean the open-source layer holds no value (Windows and iOS clearly do!). You can still create value via open-source cloud business models, such as Databricks, MongoDB, and Chronosphere.

In the earlier article, the author emphasized how adjacent layers benefit from large cloud platforms. But with open-source foundational models, we now see part of the value previously captured by OpenAI or Google shifting toward LLM-centric applications, startups, and infrastructure. OpenAI and Google can still capture value—the ability to build and run giant models remains a moat. Developer communities and network effects remain moats too—but in a world with open-source alternatives, these moats capture less value.

In this article, we’ll revisit traditional tech company moats, how they’re being disrupted, and why today’s startups must build intelligent systems—AI-driven applications—as the “new moats.” Companies can build various types of moats and evolve them over time.

Traditional Business Moats

To build a sustainable, profitable business, you need strong defensive moats. This is especially important during this era of massive platform shifts—apps moving to the cloud, consumed on iPhone, Echo, and Tesla, built on open source, and driven by AI and data. These changes have made some traditional moats obsolete, leaving CEOs feeling defenseless.

01. Economies of Scale

Some of the greatest and oldest tech companies have strong moats. For instance, Microsoft, Google, and Facebook (now Meta) have moats based on economies of scale and network effects.

At this moment of technological transformation, foundational models—trained on billions or trillions of parameters—are key to building valuable AI products. Training them requires hundreds of millions of dollars and massive computing resources. Without LLaMA’s release, most of this value might have gone to companies like Google or well-capitalized startups like OpenAI, Anthropic, and Inflection. The central question is the balance between trillion-parameter models and smaller ones. If the race favors ever-larger models, then scale itself may become the ultimate moat.

The larger a product scales, the greater its operational leverage—and the lower its costs. SaaS and cloud services enjoy strong economies of scale: you can grow revenue and customers while keeping core engineering relatively stable.

The three major cloud providers—AWS, Microsoft, and Google—are leveraging economies of scale and network effects to stay competitive in the AI boom. Training AI models has become a data-center-scale challenge, combining computing and networking into supercomputer-sized infrastructures.

Dependence on large cloud providers to run complex ML models has even revived Oracle as a preferred partner. Initially lagging in cloud servers, Oracle caught up through partnerships with NVIDIA and a series of AI-focused moves. Oracle now collaborates with leading startups including Adept, Character, and Cohere.

02. Network Effects

Metcalfe’s Law suggests that if every additional user adds value for all others, your product has “network effects.” Messaging apps like Slack and WhatsApp, and social networks like Facebook, are classic examples. Operating systems like iOS, Android, and Windows also exhibit strong network effects—the more users adopt them, the more apps are built on top.

One of the most successful cloud providers, AWS, combines both scale advantages and powerful network effects. Because “that’s where the customers and data are,” more applications and services get built on AWS. In turn, the infrastructure ecosystem attracts more customers and developers, who build more apps and generate more data—creating a virtuous cycle while lowering Amazon’s costs through scale.

First movers among innovators can establish network effect moats. OpenAI is rapidly building the first such moat around its models. Its function calling and plugin architecture could turn OpenAI into a new “AI cloud.” But the race for network effects is far from over—many players are expanding the concept, creating agents like LlamaIndex, Langchain, AutoGPT, BabyAGI, all aiming to automate parts of your apps, infrastructure, or life.

03. Deep Tech / IP / Industry Expertise

Most tech companies start with proprietary software or methods. These trade secrets may include core solutions to hard technical problems, new inventions, processes, or technologies, later protected by patents (IP). Over time, a company’s IP may evolve from specific engineering solutions to accumulated operational knowledge or deep insights into problems or processes.

Today, some AI companies are building their own models—used both in apps and offered as services. Startups in this space include Adept, Inflection, Anthropic, Poolside, Cohere, etc. As mentioned, a key consideration is the cost of training these models. It remains to be seen whether pioneers like OpenAI and Google can use their deep tech to build lasting moats—or if they’ll eventually just be another model amid open-source and academic advances.

04. High Switching Costs

Once customers adopt your product, you want it to be as hard as possible for them to switch. You achieve this through standardization, lack of alternatives, integration with other apps and data sources, or by embedding your product deeply into valuable workflows. Any of these creates stickiness—a form of lock-in that makes departure difficult.

An interesting question is whether switching costs exist at the model or application layer. For example, Midjourney has millions using its diffusion model for image generation. How hard would it be for Midjourney to replace its own model if a better one emerged? And how hard would it be for users to switch to another app? Over the next few years, we’ll see companies trying to build switching costs at both application and potential model layers.

05. Brand / Customer Loyalty

A strong brand can serve as a moat. With every positive interaction, brand strength grows over time—but if customers lose trust, that strength vanishes quickly.

In AI, trust is crucial—but for many, it hasn’t yet been earned. Early AI models suffer from “hallucinations,” giving wrong answers or exhibiting strange behaviors (e.g., Sydney in Bing). A race will emerge to build trustworthy AI and tools like Trulens to earn customer confidence.

Traditional Moats Are Being Reshaped

Strong moats help companies survive major platform shifts—but survival shouldn’t be mistaken for thriving.

For example, high switching costs partly explain why mainframes and “big iron” systems still exist decades later. Legacy enterprises with strong moats may no longer be high-growth powerhouses, but they still generate profits. Companies must recognize and adapt to industry-wide shifts or risk becoming victims of their own success.

“Switching cost” as a moat: x86 server revenue didn’t surpass mainframe and other “big iron” revenue until 2009.

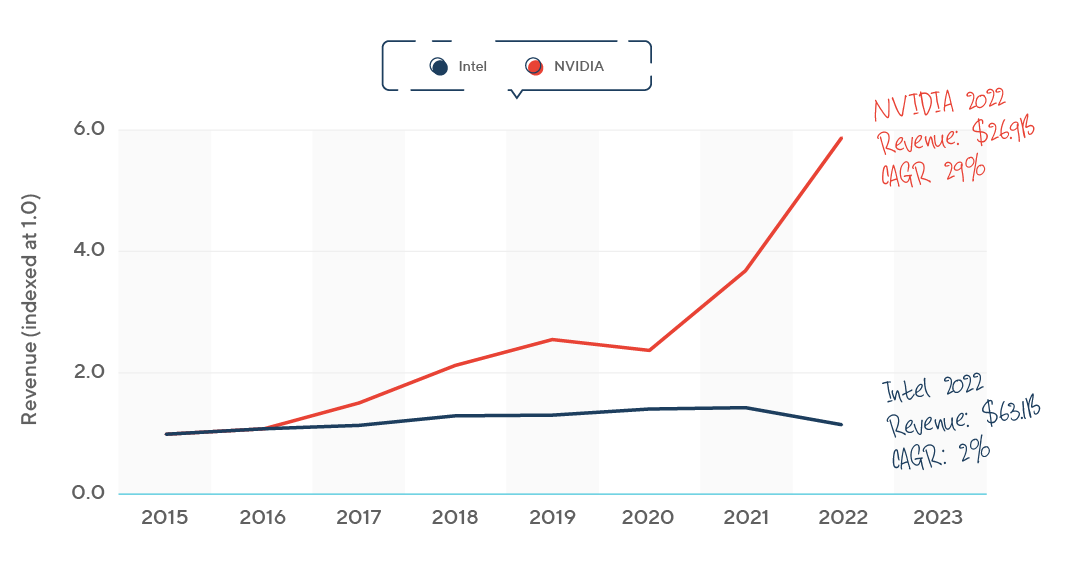

We can observe the shift to AI platforms through the financial performance of GPU leader NVIDIA and CPU leader Intel. In 2020, NVIDIA surpassed Intel as the most valuable chipmaker. By 2023, it reached a $1 trillion market cap.

Major platform shifts—like cloud and mobile—create waves of opportunity for new entrants, allowing founders to build on or bypass existing moats.

Successful startup founders often take a dual approach: 1) attack incumbents’ moats; 2) simultaneously build their own defensible moats aligned with new trends.

AI is becoming today’s platform technology, and this new LLM wave has the potential to disrupt hierarchies among established players. For example, Microsoft Bing—long criticized—may finally break Google’s search moat through integration with OpenAI’s ChatGPT.

Similarly, despite Facebook’s dominant social network, Instagram built a mobile-first photo app and rode the smartphone wave to a billion-dollar acquisition. In enterprise software, SaaS companies like Salesforce disrupted on-premise vendors like Oracle. Now, with cloud computing, AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud provide direct channels to customers. These shifts also redefine buyer and end-user roles: from central IT teams, to office knowledge workers, to iPhone users, to any developer with a GitHub account.

Today, new LLMs have created a new user category: prompt engineers. As generative AI models train across industries, user roles become broader and more diverse. Whether the role of prompt engineer persists as AI becomes intrinsic to every product remains to be seen.

New Moats?

During this wave of disruption, is it still possible to build sustainable moats? Founders may feel every advantage they build can be copied—or believe moats only exist at scale. Open-source tools and cloud computing have shifted power to “the new incumbents”—companies with scale, strong distribution, high switching costs, and strong brands. These include Apple, Facebook, Google, Amazon, and Salesforce.

Why does it feel like “no moats” can be built? In the age of cloud and open source, deep tech solving hard problems has become a shallower moat. Open source makes it harder to monetize technical progress, while cloud delivery shifts defensibility to other parts of the product. Companies overly focused on tech without framing it around customer problems get stuck “between open source and cloud.” For example, proprietary databases like Oracle face attacks from open-source alternatives (Hadoop, MongoDB) and cloud innovations (Amazon Aurora, Google Spanner). In contrast, companies building great customer experiences gain defensibility through software workflows.

We believe deep tech moats haven’t disappeared entirely—reliable business models can still be built around IP. If you pick a domain in the tech stack and become the absolute best solution, you can build a valuable company. But this means choosing problems with few alternatives, requiring difficult engineering and operational knowledge to scale.

Foundational models are one of today’s deep tech/IP moats. Owners publish APIs and plugins while continuously improving internally. Developers can easily build apps atop open-source LLMs, spawning countless startups offering niche products. But it’s now clear most startups at this layer lack sufficient moats. They risk being labeled as having “thin IP” (essentially simple wrappers around ChatGPT) and face direct competition from foundational model providers, as seen with OpenAI vs. Jasper.

One possibility: large models solve broad complex problems, while smaller models tackle specific tasks or power edge devices like phones, cars, or smart homes.

Today’s market favors “full-stack” companies—SaaS products offering application logic, middleware, and databases. Technology is becoming an invisible component of complete solutions (e.g., “Who cares which database your favorite app uses, as long as your food arrives on time!”). In consumer tech, Apple popularized seamless hardware-software integration. This full-stack experience is now dominating enterprise software too. Cloud and SaaS enable cost-effective direct customer access. Thus, customers increasingly prefer full-stack SaaS applications over buying individual stack components and building custom apps. The focus on full application experience—or the “top of the stack”—is why the author evaluates companies through an additional lens: the enterprise system stack.

The Enterprise System Stack

01. Systems of Record

At the base of any system is the database, with applications built on top. When data and apps support critical business functions, they become a “system of record.” Enterprises have three main systems of record: customers, employees, and assets. CRM manages customers, HCM manages employees, ERP/finance manages assets.

Generations of companies have been built around owning a system of record—each tech wave producing new winners. In CRM, Salesforce replaced Siebel as the system of record for customer data; Workday replaced Oracle PeopleSoft for employee data, and expanded into financial data. Other apps can build around systems of record, but are usually less valuable. For example, marketing automation firms like Marketo and Responsys built large businesses around CRM but never achieved Salesforce’s strategic importance or valuation.

Foundational models don’t replace existing systems of record—they unlock value and understanding within them. As noted, several foundational models exist today. Whether the world evolves toward a few large models refined for different uses, or a market for smaller specialized models, remains debated. Either way, these models are key components of the “intelligent systems” described in the 2017 “New Moats” article.

02. Systems of Engagement

Systems of Engagement™ act as interfaces between users and systems of record. They can become powerful businesses by controlling end-user interactions.

In the mainframe era, record and engagement systems were bundled—the mainframe and terminal were essentially the same product. The client-server wave brought companies vying for desktop dominance, later disrupted by browser-based, then mobile-first companies.

Today’s contenders for engagement system ownership include Slack, Amazon Alexa, and startups building voice/text/conversational interfaces. In China, WeChat has become the dominant engagement system, evolving into an all-in-one platform spanning e-commerce to gaming.

Engagement systems may turnover faster than record systems. Past generations don’t disappear—they coexist as users add new ways to interact with apps. In a multi-channel world, owning the engagement system is most valuable—especially if you control most end-user touchpoints or operate cross-channel, reaching users wherever they are.

One of the most strategic advantages of owning an engagement system is the ability to coexist with multiple record systems and collect all data flowing through your product. Over time, you can leverage accumulated data to transform your engagement position into an actual system of record.

Six years ago, the author highlighted chat as a new engagement system. Slack and Microsoft Teams aimed to become the primary enterprise engagement system with chat front-ends for enterprise apps—but fell short. That chat-first vision hasn’t materialized—yet foundational models may change that. Instead of opening Uber or Instacart, we might soon ask our AI assistant to order dinner or plan vacations. In a future where everyone has their own AI assistant, all interactions may resemble messaging. AI-powered voice assistants like Siri and Alexa may be replaced by intelligent chat systems like Pi (Inflection.ai’s personal intelligence agent).

OpenAI’s release of plugins and function calls is creating a new way to build and distribute apps—effectively making GPT a new platform. In this world, chat could become the front door to almost everything—the daily engagement system. How AI app UX evolves will be fascinating to watch. While chat seems dominant today, we expect multimodal interaction models to create new engagement systems beyond chat.

03. New Moat: Intelligent Systems (Systems of Intelligence)

Intelligent systems remain the new moat.

“What is an intelligent system, and why is it so defensible?”

Intelligent systems are valuable because they span multiple datasets and systems of record. For example, combining web analytics, customer data, and social data to predict user behavior, churn, lifetime value (LTV), or deliver timely content. You can build intelligence on a single data source or record system, but that position is vulnerable to competition from the data owner.

For startups to thrive alongside legacy giants like Oracle and SAP, they must combine their data with other sources (public or private) to create customer value. Incumbents have advantages in their own data—e.g., Salesforce is building Einstein, an intelligent system starting from its CRM system of record.

Since proposing the “intelligent system” concept six years ago, we’ve seen incredible AI applications emerge—Tome, Notable Health, RunwayML, Glean, Synthesia, Fermat, and thousands of others. While it’s unclear exactly where value will accumulate in this emerging stack, the shift offers abundant opportunities for startups.

Yet, as previously noted, we didn’t anticipate the transformative power of large language models—which have dramatically increased the value of the intelligent systems we envisioned.

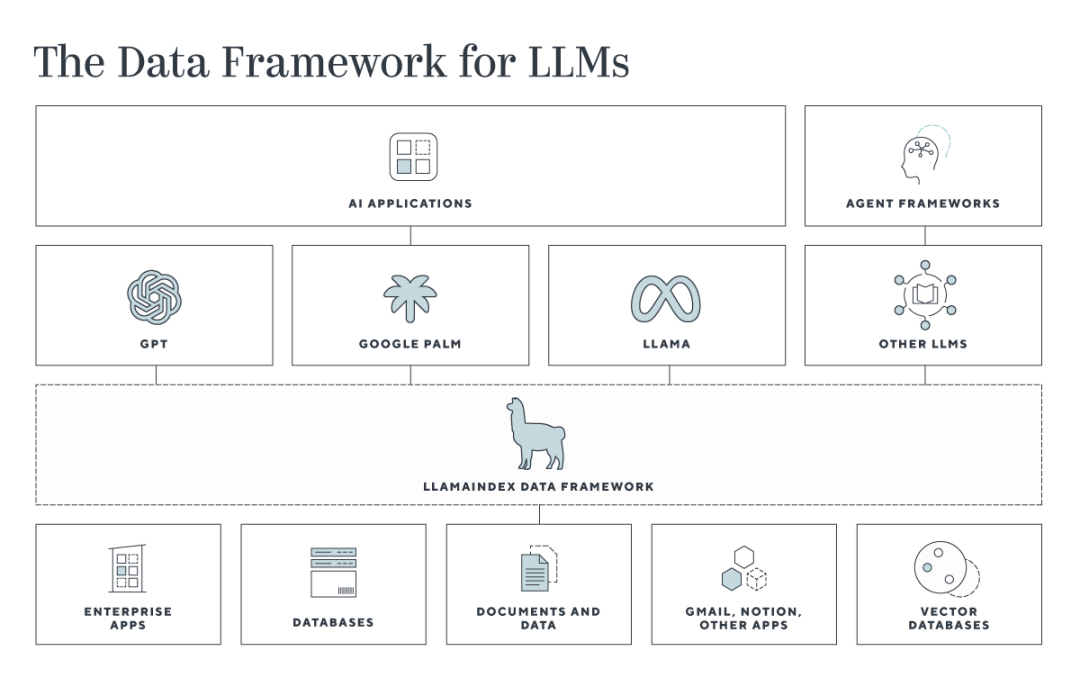

A “new stack” has emerged within LLM applications—including new middleware tools for chaining prompts or composing models. Just as companies emerged to make cloud and storage easier to manage, we now see startups focused on making foundational models easier to use.

This new middleware stack will include data frameworks like LlamaIndex, connecting enterprise data to LLMs; agent frameworks like Langchain, for building apps and linking models. Additionally, a new generation of security and observability tools will be needed to ensure reliability and safety of these applications.

The next generation of enterprise products will use diverse AI technologies to build intelligent systems. Not only applications, but data centers and infrastructure products will transform. Key areas for intelligent systems fall into three categories: customer journey–centric applications, employee-facing apps (e.g., HR, ITSM, finance), and infrastructure systems (e.g., security, compute/storage/networking, monitoring/management). Beyond these horizontal use cases, startups can target vertical markets—building intelligent systems on unique data in fields like life sciences (Veeva) or construction (Rhumbix).

Past applications digitized processes—but these new AI apps risk replacing humans, or positively viewed, enhancing human capabilities and boosting individual productivity.

AI tools already exist to make design, coding, data processing, legal work, and more accurate and faster. In law, companies like Harvey.AI and Even Up Law perform tasks of legal assistants and lawyers. GitHub Copilot multiplies developer productivity—new coders can write like seasoned pros. Designers using Adobe’s Firefly create digital imagery that once required entire teams. Productivity apps like Tome, Coda, and Notion give every office worker new superpowers, accelerating speed and output. These are truly the AI-powered “Iron Man suits” promised by technology. As we grow more dependent on AI applications, managing and monitoring trustworthy AI becomes critical—to avoid decisions based on hallucinations.

In all these markets, competition is shifting from old barriers (source of data) to new ones (how data is used). Leveraging company data enables selling value-added products, auto-replying support tickets, preventing employee churn, and detecting security anomalies. Products using industry-specific (healthcare, finance) or company-specific (customer data, machine logs) data to solve strategic problems represent deep moats—especially if AI can replace or automate entire workflows, or create new value-added workflows enabled by this intelligence.

Enterprise apps that become systems of record have always been strong business models. Enduring companies like Salesforce and SAP are built on deep IP, benefit from economies of scale, and over time accumulate more data and operational knowledge within company workflows. Yet even these giants aren’t immune to platform shifts—new companies are attacking their domains.

Indeed, we may risk fatigue from AI hype—but the buzz reflects AI’s real potential to transform industries. Machine learning (ML) is a popular AI method that, combined with data, business processes, and workflows, provides context for building intelligent systems. Google pioneered applying ML to workflows—collecting more user data and using ML to deliver timely ads in search. Other AI technologies like neural networks will continue reshaping expectations for future applications.

On two points, however, the author admits past misjudgments: First, AI won’t lead to fatigue. We’re witnessing the dawn of the next great tech wave—excitement is naturally high. Second, foundational models have become the most transformative advance in AI. Many prior ML/AI companies now risk being overtaken by the latest LLMs.

AI-powered intelligent systems offer tremendous opportunities for startups. Companies succeeding here can build virtuous data cycles: the more data you generate and use to train your product, the better your model and product become. Eventually, products tailor to each customer—forming another moat: high switching costs. It’s possible to build a company combining engagement, intelligence, and even entire enterprise tech stacks—but engagement or intelligence systems offer the best entry points for startups against incumbents. Building either is non-trivial—it demands deep technical expertise, especially in speed and scale. Technologies enabling intelligent layers across multiple data sources will be essential.

We’re already seeing these data flywheels in action—not just raw data for training models, but feedback loops between user data, models, and apps—even reinforcement learning in extreme cases. Over time, all this strengthens the data moat.

Personal AI tools like ChatGPT or Inflection AI’s Pi have clear potential to become the primary channel for every task—accessing apps, developing software, communicating. Meanwhile, data frameworks like LlamaIndex will be key to connecting personal data with LLMs. The combination of models, usage data, and personal data will create personalized application experiences for each user or company.

Finally, some companies can train and improve models using customer and market data—delivering better products for all users and accelerating intelligence development.

Startups can build defensible business models as engagement, intelligence, or record systems. With AI, intelligent applications will become the source of the next great software companies—because they are the new moats.

Old Moats Are the New Moats

The rise of AI is exciting, and startups exploring new moats have come full circle. It turns out the old moats matter more than ever. If Google’s “we have no moat” prediction comes true—and AI models let any developer with access to GPT or LLaMA build intelligent systems—how do we build sustainable businesses? The value of applications lies in how value is delivered. Workflows, integration with data and other apps, brand/trust, network effects, scale, and cost efficiency all create economic value and defensibility. Companies building intelligent systems still need mastery in go-to-market. They must not only nail product-market fit, but product-to-GTM fit.

AI doesn’t change how startups market, sell, or partner. AI reminds us that while each tech generation has its foundation, the fundamentals of company building remain unchanged.

The old moats are indeed the new moats.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News