Cobo DeFi Security Class (Part 1): Retrospective of 2022's Major DeFi Security Incidents

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Cobo DeFi Security Class (Part 1): Retrospective of 2022's Major DeFi Security Incidents

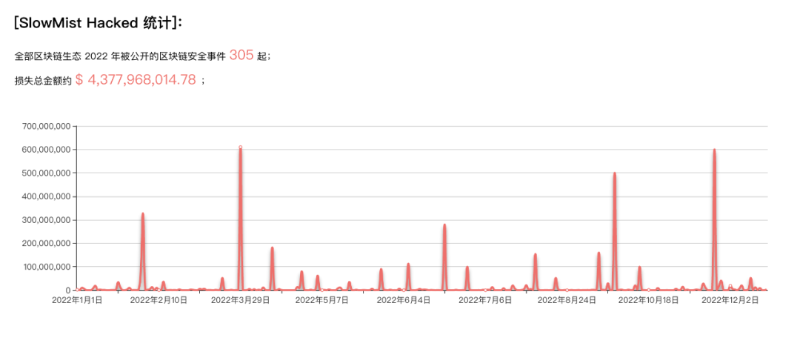

According to SlowMist's statistics, over 300 blockchain security incidents occurred in 2022, involving a total of $4.3 billion.

Author: Max, Cobo Security Director

Invited by Moledao, Max, Security Director at Cobo, recently delivered a DeFi security lecture online to community members. Max reviewed major security incidents that occurred in the Web3 industry over the past year, focusing on their root causes and how to avoid them. He summarized common smart contract vulnerabilities and preventive measures, and provided security recommendations for both project teams and general users. Here, we are publishing Max’s presentation in two parts for DeFi enthusiasts to save and reference.

According to SlowMist statistics, more than 300 blockchain security incidents occurred in 2022, involving a total of $4.3 billion.

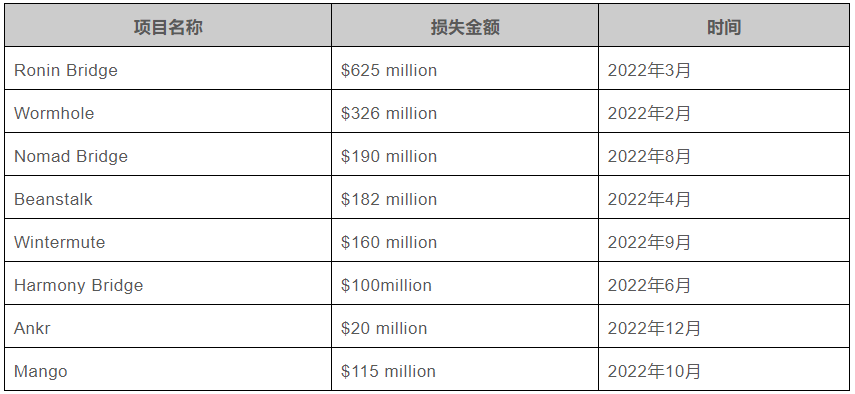

This article provides an in-depth analysis of eight representative cases, each resulting in losses exceeding $100 million. Although Ankr involved a smaller amount, it remains a typical case worth examining.

Ronin Bridge

Event Recap:

-

On March 23, 2022, the NFT game Axie Infinity’s sidechain Ronin Network announced that early investigations revealed its Sky Mavis-operated Ronin validator node and Axie DAO validator node had been compromised, leading to the bridging of 173,600 ETH (worth over $590 million at current prices) and 25.5 million USD across two transactions.

-

The U.S. Department of Treasury stated that the North Korean hacking group Lazarus was linked to the $625 million hack of Axie Infinity’s Ronin Network.

-

According to media citing sources, hackers contacted an employee at Sky Mavis, Axie Infinity’s developer, via LinkedIn, conducted several interview rounds, and eventually informed the employee they were hired with a high salary. The employee then downloaded a forged job offer letter disguised as a PDF document, which allowed malware to infiltrate Ronin’s systems. Hackers subsequently gained control of four out of nine validators on the Ronin network—just one short of full control—and further exploited an unrelinquished permission from Axie DAO to complete the breach.

The North Korean hacking group has existed for many years. Even before Web3 technologies became widespread, there were multiple reports of banks and large commercial institutions being breached. Now, more traditional hacker groups and even state-sponsored actors have shifted from stealing data and credit card information to attacking blockchain projects to directly obtain financial gains.

The attack method used in this incident is highly typical, known in traditional cybersecurity as APT—Advanced Persistent Threat. Once a target is identified, hacker groups use social engineering techniques to first compromise a computer within the target organization as a foothold, gradually expanding access until the ultimate objective is achieved.

This event also exposed weak security awareness among Axie Infinity employees and flaws in the company’s internal security framework.

Wormhole

Event Recap:

-

According to Wormhole’s official report on the incident, the vulnerability stemmed from a flaw in the signature verification code of the core Wormhole contract on the Solana side, allowing attackers to forge messages from “guardians” to mint wrapped ETH on the Ethereum side, resulting in a loss of approximately 120,000 ETH.

-

Jump Crypto injected 120,000 ETH to cover the losses incurred by the Wormhole bridge hack, supporting Wormhole’s continued development.

The issue encountered by Wormhole was primarily at the code level—it used deprecated functions. Taking Ethereum as an example, certain functions in early versions of Solidity were poorly designed and have since been deprecated through updates. Similar situations exist across other ecosystems. Therefore, developers are advised to always use the latest versions to prevent such issues.

Nomad Bridge

Event Recap:

-

The cross-chain interoperability protocol Nomad Bridge suffered a hack because its Replica contract set the trusted root to 0x0 during initialization, and failed to invalidate the old root when updating it. This allowed attackers to craft arbitrary messages to steal funds locked in the bridge, extracting over $190 million in value.

-

The attacker exploited this vulnerability by repeatedly broadcasting crafted transaction data based on valid past transactions, draining nearly all funds locked in the Nomad Bridge.

-

PeckShield monitoring showed that around 41 addresses profited approximately $152 million (about 80%) from the Nomad hack, including about seven MEV bots ($7.1 million), the Rari Capital hacker ($3.4 million), and six white-hat hackers ($8.2 million). About 10% of ENS domain addresses earned $6.1 million.

The Nomad Bridge incident is highly representative. At its core, the problem originated from flawed initial configuration—if hackers found previously valid transactions and rebroadcast them, those transactions would re-execute and return profits to the attacker. Within the Ethereum ecosystem, participants include not only projects and users but also numerous automated MEV bots. In this case, once bots detected that broadcasting the malicious transaction would yield profit regardless of who sent it, anyone capable of covering gas fees rushed to rebroadcast it, turning the entire event into a free-for-all money grab. The number of involved addresses was extremely high. Although the team later recovered some funds by contacting certain ENS holders and white-hat hackers, most assets remain unrecovered. If the attacker uses a completely clean device and fresh addresses, tracing the individual behind the activity becomes nearly impossible through data correlation.

While companies like Google, Microsoft, Facebook, Alibaba, and Tencent have also experienced hacks, their software is typically closed-source. In contrast, within the Ethereum or broader smart contract ecosystem, much of the code is open-source, making it relatively easier for hackers to analyze. Thus, when a project has a vulnerability, its failure is essentially declared from the moment it goes live.

Beanstalk

Event Recap:

-

The Ethereum-based algorithmic stablecoin project Beanstalk Farms lost approximately $182 million in a flash loan attack, including 79,238,241 BEAN3CRV-f tokens, 1,637,956 BEANLUSD-f tokens, 36,084,584 BEAN tokens, and 0.54 UNI-V2_WETH_BEAN LP tokens. The attacker profited over $80 million, including about 24,830 ETH and 36 million BEAN.

-

The main cause of this attack was the lack of any time delay between proposal voting and execution phases, enabling the attacker to execute a malicious proposal immediately after passing the vote without community review.

-

Attack Process:

-

Purchased and staked tokens a day in advance to gain proposal eligibility; created a malicious proposal contract;

-

Used a flash loan to acquire a large number of tokens to vote for the malicious proposal;

-

Executed the malicious proposal to complete arbitrage.

-

Beanstalk is another classic example—the attacker did not exploit a technical bug but rather leveraged a flaw in the project’s mechanism. Under this system, anyone who stakes tokens can submit a proposal, which itself is a smart contract. The attacker purchased tokens the day before the attack, submitted a malicious proposal, waited 24 hours for voting eligibility, and upon approval—with no time lock or cooling-off period—immediately executed the proposal.

Many projects today emphasize community governance using fully decentralized models, which often leads to problems. For instance, does every proposal undergo scrutiny? How can one distinguish between legitimate and malicious proposals? If a proposal passes, should flash-loan-funded voting be sufficient, or should mechanisms require token staking over time—or issuance of dedicated voting tokens—before participation? Should there be a time lock between proposal approval and execution? In theory, yes—this provides a window for users to react and exit if needed. Without it, if a malicious action executes, no one can escape.

Wintermute

Event Recap:

-

On the morning of September 21, 2022, Evgeny Gaevoy tweeted an update confirming that Wintermute had indeed used Profanity along with an internal tool in June to generate wallet addresses. The reason was to optimize gas fees—not merely to create vanity addresses. He added that after learning about Profanity’s vulnerability the previous week, Wintermute accelerated deprecation of old keys. However, due to an internal (human) error, the wrong function was called, so infected addresses’ signing and execution permissions were not removed.

Online, we often see Ethereum addresses starting with eight zeros—the more zeros in an address, the lower the gas fee. As a result, many MEV frontrunning bots and projects prefer such addresses, especially for high-frequency operations.

Wintermute is a market maker that transferred many tokens into a contract and used a vanity address generator to create the contract address. The contract owner was also a vanity address—unfortunately, its private key was brute-forced by an attacker, allowing all funds in the contract to be drained.

When using open-source tools online, one must be prepared for potential adverse consequences. When adopting third-party software, it is strongly recommended to conduct thorough security assessments beforehand.

Harmony Bridge

Event Recap:

-

The Horizon cross-chain bridge lost over $100 million, including more than 13,000 ETH and 5,000 BNB.

-

Harmony’s founder stated the Horizon breach resulted from a private key leak.

-

According to Bloomberg, Elliptic, a blockchain research firm, concluded that the Lazarus Group—a suspected North Korean hacking collective—was likely behind the $100 million theft from Harmony’s Horizon bridge. Elliptic highlighted key indicators linking the attack to Lazarus, including programmed laundering via Tornado.Cash mimicking the Ronin Bridge incident and timing patterns.

Harmony did not disclose detailed technical specifics, but subsequent reports suggest involvement of the North Korean hacker group. If confirmed, the attack method aligns with that used in the Ronin Bridge incident. North Korean hacking groups have been highly active in recent years, particularly targeting cryptocurrency projects, with many companies having recently suffered phishing attacks from them.

Ankr

Event Recap:

-

Ankr: Deployer update contract.

-

Ankr: Deployer transferred BNB to Ankr Exploiter.

-

Ankr Exploiter minted tokens via the updated contract’s minting function.

-

10 trillion aBNBc tokens were minted out of thin air. Hacker A swapped 5 million USDC from PancakeSwap, draining the liquidity pool and causing aBNBc’s value to collapse. Hacker A later bridged the stolen funds to Ethereum and deposited them into Tornado Cash.

-

About half an hour after Hacker A’s minting, aBNBc crashed sharply, creating an arbitrage opportunity. Arbitrageur B exploited the price discrepancy between the market and Helio’s oracle—which uses a 6-hour time-weighted average—by swapping aBNBc for hBNB, then staking hBNB to borrow HAY stablecoins, converting them into BNB and USDC. This drained the HAY liquidity pool, netting over $17 million in equivalent value.

-

Ankr will allocate funds from its $15 million recovery fund to buy back newly issued HAY tokens to compensate victims of the attack.

Ankr’s overall loss was relatively small, so we discuss it separately. Many DeFi projects today resemble Lego blocks—A depends on B, B on C, forming complex interdependencies. When one component fails, the entire upstream and downstream chain may suffer cascading effects.

Later, Ankr published an explanation attributing the incident to a former insider acting maliciously. Key issues exposed: First, the staking contract owner was an externally owned account (EOA) instead of a multisig wallet—meaning whoever controls the private key fully controls the contract, which is inherently insecure. Second, the Deployer’s private key remained accessible to so-called core employees—even after departure. This indicates the internal security system effectively failed.

Mango

Event Recap:

-

The hacker started with $10 million USDT split across two accounts.

-

Step 1: The hacker deposited $5 million each into Mango’s trading platform under addresses A and B.

-

Step 2: Using address A, the hacker opened a short position on MNGO perpetual contracts at $0.0382, totaling 483 million MNGO. Simultaneously, using address B, the hacker opened a long position on MNGO at the same price and size. (The dual long-short setup was necessary because Mango’s order book depth was shallow; without self-matching, achieving such large positions would be difficult.)

-

Step 3: The hacker manipulated MNGO’s spot price upward by 5–10x across multiple exchanges (FTX, Ascendex). This price feed propagated via Pyth Oracle to Mango, triggering further price increases. Eventually, MNGO’s price on Mango surged from $0.0382 to a peak of $0.91.

-

Step 4: The long position yielded approximately $420 million (483 million × ($0.91 – $0.0382)). The hacker then borrowed close to $115 million from Mango using the inflated net asset value. Fortunately, limited platform liquidity prevented larger withdrawals.

-

After the attack, the hacker proposed using treasury funds ($70 million) to repay protocol bad debt. The treasury held about $144 million, including $88.5 million in MNGO and nearly $60 million in USDC. The hacker offered to return part of the stolen funds if authorities waived criminal prosecution and froze no assets: “If this proposal passes, I will send MSOL, SOL, and MNGO from this account to the address published by the Mango team. The treasury will cover remaining bad debt, ensuring full compensation for affected users… No criminal investigation or fund freezing will occur once tokens are returned as described.”

-

According to CoinDesk, Avraham Eisenberg—the publicly identified Mango attacker—was arrested in Puerto Rico on December 26, 2022. He faces charges of commodities fraud and manipulation, which could lead to fines and imprisonment.

The Mango incident can be classified either as a security incident or as arbitrage, since the issue wasn’t a code-level vulnerability but a business logic flaw. While the platform lists high-market-cap assets like BTC and ETH, it also includes low-liquidity tokens like MNGO. During bear markets, such small-cap tokens can be easily manipulated with minimal capital, making position risk management extremely challenging for perpetual futures platforms.

Therefore, project teams must consider all possible scenarios thoroughly. During testing, edge cases beyond expected conditions should be included in test suites.

For ordinary users, participating in a project shouldn’t be driven solely by returns—principal safety must also be evaluated. Beyond technical vulnerabilities, one should carefully assess whether the project’s business model contains exploitable weaknesses.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News