Entretien approfondi avec Zhang Ye de Scroll : zkEVM, Scroll et ses perspectives d'avenir

TechFlow SélectionTechFlow Sélection

Entretien approfondi avec Zhang Ye de Scroll : zkEVM, Scroll et ses perspectives d'avenir

Cet article est une ressource excellente pour comprendre Scroll. Zhang Ye répond à 15 questions sur Scroll et zkEVM.

Interviewers : Nickqiao & Faust, Geek Web3

Interviewee : Ye Zhang, Co-founder of Scroll

Editors : Faust, Jomosis

On June 17, with the help of Vincent Jin, DevRel at Scroll, Geek Web3 and BTCEden were honored to invite Ye Zhang, co-founder of Scroll, to answer many questions about Scroll and zkEVM.

During the discussion, both technical topics and fun stories about Scroll were covered, along with its grand vision of empowering real economies in Africa, Latin America, and Asia. This article is a written transcript of that interview, exceeding 10,000 words and covering at least 15 key topics:

-

Applications of ZK beyond blockchain

-

Differences in engineering difficulty between zkEVM and zkVM

-

Technical challenges faced by Scroll during zkEVM implementation

-

Scroll’s improvements to Zcash’s halo2 proof system

-

How Scroll collaborates with Ethereum’s PSE team

-

How Scroll ensures circuit security through code audits

-

Scroll’s roadmap for next-generation zkEVM and proof systems

-

Scroll’s Multi-Prover design and how it builds its Prover network (zk mining pool), etc.

In addition, Mr. Zhang shared Scroll’s ambitious vision at the end — to establish roots in underdeveloped financial regions such as Africa, Turkey, and Southeast Asia, creating real-world economic use cases to transition from speculative to tangible applications. This article may be one of the best resources for understanding Scroll more deeply. We highly recommend reading it carefully.

1. Faust: What are your thoughts on applications of ZK outside Rollups? Many people assume ZK is mainly useful for mixers, private transfers, ZK Rollups, or ZK bridges. But outside Web3, traditional industries already have various uses for ZK. Where do you think ZK will see the most adoption in the future?

Ye Zhang: That's an excellent question. People working on ZK in traditional industries have been exploring its potential for five or six years now. The blockchain use cases for ZK are actually quite small compared to broader possibilities — which is why Vitalik believes that in ten years, ZK applications could be as large as blockchain itself.

I believe ZK has great potential wherever trust assumptions exist. Imagine you need to perform a heavy computation task. If you rent servers on AWS, run your job there, and get results, it's like doing computation on equipment you control — but you pay a high price for server rental, which often isn't cheap.

But what if we adopt a computing outsourcing model? Many people could share their idle devices or resources to handle parts of your computation, potentially reducing costs significantly. However, this raises a trust issue — you can’t verify whether the results returned are correct. Suppose you give me a complex calculation to perform and promise payment. After half an hour, I return any arbitrary result — you’d have no way of knowing whether it was valid, since I could fabricate anything.

However, if I can prove to you that the computed result is accurate, then you can trust it and feel confident delegating more tasks to me. ZK allows untrusted data sources to become trustworthy — a powerful capability. With ZK, you can efficiently utilize third-party computational resources that are inexpensive yet untrusted.

I think this scenario holds tremendous significance and could give rise to new business models around outsourced computing. In academic literature, this concept is known as verifiable computation — making computations inherently trustworthy. Beyond that, ZK can also apply to database systems. For instance, running a local database might be too expensive, so you opt for outsourcing. Someone else has spare database capacity, and you store your data with them. But you worry they might alter your data or return incorrect query results after executing your SQL commands.

To address this, you could require them to generate a cryptographic proof. If feasible, you could safely outsource not only storage but also obtain trustworthy query responses. This aligns closely with verifiable computation as another major category of application scenarios.

There are numerous other examples. I recall a paper discussing Verifiable ASICs, where ZK algorithms are embedded directly into chips during manufacturing. When programs run on these chips, outputs automatically come with attached proofs. This would allow any device to act as a trusted agent producing verifiable results.

Another rather unusual idea is Photo Proof — proving authenticity of photos. Today, we often cannot tell whether images have been edited. Using ZK, we could prove a photo hasn’t been tampered with. For example, camera software could include settings that automatically generate digital signatures when taking pictures, effectively "stamping" each image. If someone later edits your photo for "remixing," signature verification would detect the alteration.

With ZK, even if minor modifications are made — say rotating or translating the image — you could prove via ZK proof that only superficial changes occurred without altering core content. You could demonstrate that your modified version remains essentially identical to the original, thereby showing no malicious manipulation took place.

This concept can extend to videos and audio files — using ZK, you don’t need to disclose exactly what changes were made to the original file, yet still prove that fundamental content remains intact, confirming only harmless adjustments were performed. There are many such interesting applications where ZK can play a role.

Currently, I believe the main reason ZK applications haven’t gained widespread adoption is cost. Existing ZK proof generation methods aren’t fast enough to support real-time proofs for arbitrary computations. The overhead of generating ZK proofs is typically 100x to 1000x the original computation — and those numbers represent optimistic estimates.

Imagine a task that normally takes one hour to compute. Generating a ZK proof could incur 100x overhead — meaning 100 hours just to produce the proof. While GPUs or ASICs can accelerate this process, massive computational resources are still required. If you ask me to compute something complicated and also generate a ZK proof, I might refuse — because it demands ~100x extra resources, making it economically impractical. Thus, generating one-off ZK proofs in point-to-point scenarios remains prohibitively expensive.

This is precisely why blockchains are especially well-suited for ZK — due to redundant computation and frequent 1-to-many scenarios. In a blockchain network, thousands of nodes perform identical computations. If there are 10,000 nodes, the same task runs 10,000 times redundantly. But if you complete the computation off-chain and submit a single ZK proof, all 10,000 nodes only need to verify the proof instead of re-executing the full computation. Effectively, you’re trading one person’s computation cost against the collective redundancy of 10,000 nodes — saving enormous overall resources.

Therefore, the more decentralized a chain is, the better it fits with ZK — because anyone can verify ZKPs at near-zero cost. By paying upfront for proof generation, you liberate everyone else from recomputation. This matches perfectly with blockchain’s public verifiability and abundant 1-to-many patterns.

One additional aspect not mentioned earlier: Most current ZK proofs used in blockchains involve high overhead and are non-interactive — you provide input, receive a proof, and that’s it. This suits blockchains, where repeated interaction with the chain isn’t practical. But there exists a more efficient, lower-overhead alternative: interactive proofs. For example, you send a challenge, I respond; you reply again, I respond once more — through multiple rounds of exchange, we might reduce the total computational burden of ZK proofs. If viable, this approach could unlock broader applications requiring scalable proof generation.

Nickqiao: What’s your view on zkML — combining ZK with machine learning? How promising is its development outlook?

Ye Zhang: zkML is indeed a fascinating direction — applying zero-knowledge techniques to machine learning. However, I feel it still lacks killer use cases. It’s widely believed that as ZK systems improve in performance, they’ll eventually support ML-scale workloads. Currently, zkML efficiency allows handling models like GPT-2 technically feasible — though limited primarily to inference rather than training. Ultimately, we’re still exploring what kinds of applications truly benefit from proving the correctness of ML inference — a subtle and challenging question.

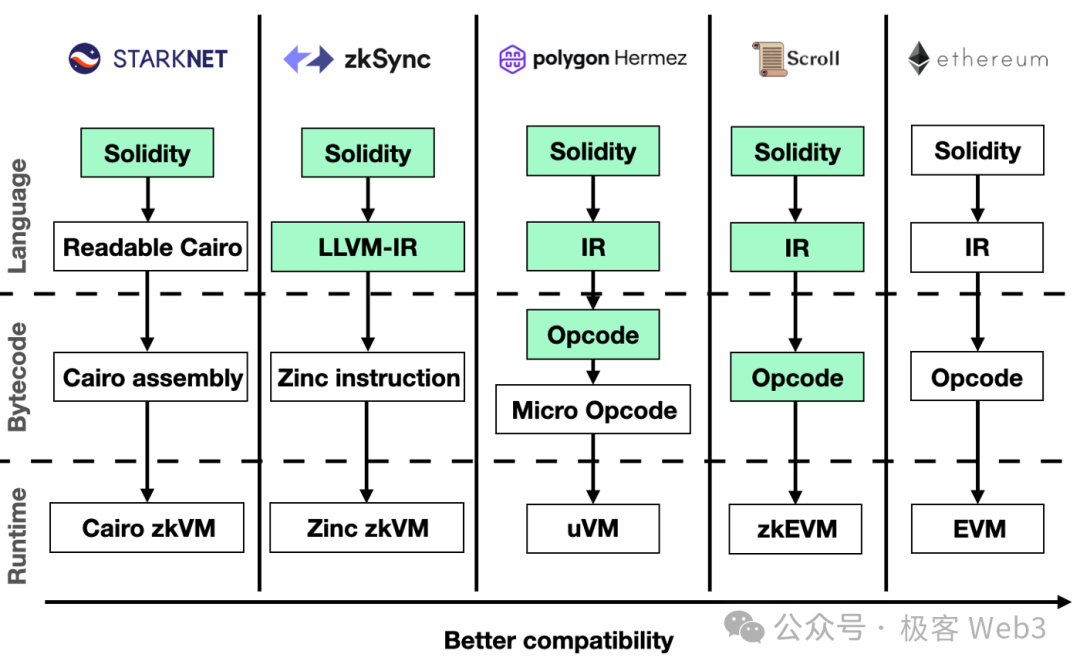

2. Nickqiao: Could you explain the difference in engineering difficulty between implementing zkEVM versus zkVM?

Ye Zhang: Fundamentally, both zkEVM and zkVM involve building custom ZK circuits tailored to a virtual machine’s opcodes/instruction set. The engineering complexity of zkEVM depends heavily on implementation choices. When we started our project, ZK efficiency wasn’t very high — so the most efficient path was writing dedicated circuits for every EVM opcode and composing them together — thus crafting a customized zkEVM.

This approach is undoubtedly far more difficult than zkVM — significantly so. After all, EVM has over 100 opcodes, each requiring a custom circuit component before integration. Whenever an EIP adds new opcodes to EVM — such as EIP-4844 — the zkEVM must similarly incorporate new components. This leads to extensive circuit development and lengthy audit processes, making development effort and workload vastly greater than for zkVM.

In contrast, zkVM defines its own instruction set, which can be designed to be extremely simple and ZK-friendly. Once built, a zkVM doesn’t require frequent low-level code changes to support upgrades or precompiles. Therefore, the primary engineering burden and maintenance difficulty shift to the compiler layer — translating smart contracts into zkVM opcodes — which differs greatly from zkEVM.

Thus, from an engineering standpoint, I believe zkVM is easier to implement than a fully customized zkEVM. However, running EVM bytecode on a zkVM generally performs much worse than a purpose-built zkEVM due to lack of specialization. That said, prover efficiency has improved dramatically over the past two years — by factors of 3–5x, sometimes even 5–10x — lifting zkVM performance accordingly. As zkVM efficiency rises, its advantages in ease of development and maintenance may outweigh its performance drawbacks. For both zkVM and zkEVM, aside from performance, the biggest bottleneck lies in development complexity — requiring exceptionally strong engineering teams to maintain such intricate systems.

3. Nickqiao: Can you share some technical difficulties Scroll encountered during zkEVM implementation, and how you resolved them?

Ye Zhang: Looking back, the biggest challenge was immense uncertainty at the outset. When we launched the project, almost no one else was building zkEVM — we were among the first teams attempting to turn zkEVM from impossible to possible. Theoretically, within the first six months, we established a viable framework. Later, actual implementation posed huge engineering challenges and highly technical obstacles, such as dynamically supporting different precompiles or efficiently aggregating opcodes — involving many deep engineering issues.

We were also the first and only team to support EC Pairing (elliptic curve pairing) as a precompile. Implementing pairing circuits is extremely difficult, involving complex mathematics and cryptography — demanding exceptional expertise in math, cryptography, and engineering from circuit developers.

Later, we had to consider long-term maintainability of our tech stack and determine when and how to upgrade to zkEVM 2.0. We have a dedicated research team actively exploring solutions — including supporting EVM via zkVM approaches, and publishing related papers on these topics.

To summarize, early challenges centered on turning zkEVM from theory into reality — focusing on engineering feasibility and optimization. Now, the next phase involves deciding when and how to migrate to a more efficient ZK proof system, transitioning our current codebase to next-gen zkEVM, and identifying what new features it could enable — areas ripe for exploration.

4. Nickqiao: It sounds like Scroll is considering switching to another ZK proof system. From what I understand, Scroll currently uses a PLONK+Lookup-based algorithm. Is this currently the optimal choice for zkEVM? And what proof system does Scroll plan to adopt in the future?

Ye Zhang: Let me briefly address PLONK and Lookup first. Currently, this combination remains among the best options for implementing zkEVM or zkVM. Most implementations are tightly coupled with specific PLONK and Lookup designs. When people refer to PLONK today, they usually mean using PLONK’s arithmetization — i.e., its method of expressing circuits numerically — to write zkVM logic.

Lookup is simply a technique and constraint type used in circuit writing. So when we say “PLONK + Lookup,” we mean using PLONK-style constraints while writing zkEVM/zkVM circuits — currently the most common approach.

On the backend, distinctions between PLONK and STARK are blurring — differing mainly in polynomial commitment schemes, otherwise quite similar. Even a STARK+Lookup setup behaves similarly to PLONK+Lookup. Differences mainly affect prover efficiency and proof size. Frontend-wise, PLONK+Lookup remains ideal for zkEVM implementation.

Regarding Scroll’s future plans, our goal is to always keep our technology and protocol framework at the cutting edge of ZK advancements. So yes, we’ll integrate newer technologies. However, prioritizing security and stability means we won’t aggressively overhaul our ZK proof system. Instead, we’ll likely transition gradually using Multi-Prover mechanisms, progressing step-by-step toward the next iteration. Above all, ensuring a smooth transition is paramount.

That said, migrating to a new proof system is still premature — this is more of a 6- to 12-month horizon.

5. Nickqiao: Has Scroll introduced any unique innovations atop its current PLONK and Lookup-based proof system?

Ye Zhang: The system currently running on Scroll’s mainnet is based on halo2, originally developed by the Zcash team. They created a backend supporting Lookup and flexible circuit formats. We collaborated with Ethereum’s PSE team to modify halo2 — replacing its IPA-based polynomial commitments with KZG, thereby shrinking proof sizes and enabling more efficient ZK proof verification on Ethereum.

Additionally, we’ve done substantial work on GPU hardware acceleration — achieving 5–10x faster ZKP generation compared to CPU-only setups. Overall, we replaced halo2’s original polynomial commitment scheme with a more verification-friendly version and implemented numerous prover optimizations — investing heavily in practical deployment.

6. Nickqiao: So Scroll now jointly maintains the KZG version of halo2 with Ethereum’s PSE team. Could you elaborate on how this collaboration works?

Ye Zhang: Before launching Scroll, we already knew several engineers from the PSE team. We discussed our intention to build zkEVM and estimated it was technically feasible. Coincidentally, they were planning the same thing — so we quickly aligned.

We met fellow zkEVM enthusiasts through the Ethereum community and Ethereum Research forums — all aiming to productize zkEVM and serve Ethereum — leading naturally to open-source collaboration. Our cooperation resembles an open-source community more than a commercial venture. We hold weekly calls to sync progress and discuss issues.

Through this open model, we co-developed the codebase — from improving halo2 to implementing zkEVM. Throughout this exploratory journey, we reviewed each other’s code. You can see from GitHub contribution stats that roughly half the code came from PSE and half from Scroll. Later, we completed audits and deployed a fully production-ready version live on mainnet. In summary, our collaboration with Ethereum PSE follows an organic, community-driven open-source path.

7. Nickqiao: Earlier, you mentioned that designing zkEVM circuits requires deep mathematical and cryptographic knowledge — implying few people truly understand zkEVM. How does Scroll ensure correctness and minimize bugs in circuit design?

Ye Zhang: Since our code is open source, nearly every PR undergoes review by our team, Ethereum contributors, and community members — following strict auditing procedures. Moreover, we’ve invested heavily in circuit audits — over $1 million — engaging top-tier cryptography and circuit auditing firms like Trail of Bits and Zellic. We also hired OpenZeppelin to audit our on-chain smart contracts. Essentially, we’ve leveraged the highest-grade security auditing resources available. Internally, we maintain a dedicated security team conducting continuous testing to enhance Scroll’s robustness.

Nickqiao: Beyond manual audits, do you employ mathematically rigorous methods like formal verification?

Ye Zhang: We’ve long explored Formal Verification (FV), and Ethereum has recently begun considering how to formally verify zkEVM — clearly a valuable direction. However, comprehensive FV for zkEVM remains premature — we can only begin experimenting with smaller modules. Running FV incurs costs: you must first write a formal specification (spec), which itself is non-trivial. Maturing this process will take considerable time.

Hence, I believe we’re not yet ready for full formal verification of zkEVM. Still, we continue collaborating externally — including with Ethereum — to explore zkEVM formal proof methodologies.

Currently, manual auditing remains the best approach, because even with specs and FV tools, errors in spec definition will lead to flawed outcomes. Therefore, for now, manual audits combined with open-sourcing and bug bounty programs remain optimal for ensuring Scroll’s code stability.

Nevertheless, in next-generation zkEVM development, defining how to conduct formal verification, designing better zkEVM architectures to simplify spec writing, and ultimately proving safety via formal methods represent Ethereum’s ultimate goals. Once a zkEVM passes formal verification, it could be confidently deployed on Ethereum’s mainnet.

8. Nickqiao: Regarding Scroll’s use of halo2, would supporting new proof systems like STARK entail significant development costs? Could a plugin architecture support multiple proof systems simultaneously?

Ye Zhang: halo2 is a highly modular ZK proof system. You can swap domains, polynomial commitments, etc. Simply changing its polynomial commitment from KZG to FRI essentially creates a halo2-based STARK — something others have already done. Thus, halo2 can natively support STARK — compatibility is fully achievable.

In practice, pursuing peak efficiency may conflict with modularity — overly modular frameworks often sacrifice performance due to abstraction overhead. We’re actively evaluating whether future directions favor modular vs. highly customized frameworks. Given our strong ZK engineering team, we could maintain a standalone proof system optimized specifically for zkEVM efficiency. Trade-offs are inevitable, but regarding halo2 — yes, FRI support is feasible.

9. Nickqiao: What are Scroll’s primary ZK-related development priorities today? Are you optimizing existing algorithms, adding new features, etc.?

Ye Zhang: The core focus of our engineering team remains doubling current prover performance while achieving maximum EVM compatibility. In the next upgrade, we aim to retain our position as the most EVM-compatible zkRollup — no other zkEVM currently surpasses us in compatibility.

This is one pillar of Scroll’s engineering efforts — continuing prover and compatibility optimization while lowering fees. We’ve already committed significant manpower — about half our engineering force — to researching next-gen zkEVM, targeting minute- or even second-level ZK proof generation, dramatically boosting prover efficiency.

Simultaneously, we’re exploring next-gen zkEVM execution layers. Previously, we used go-ethereum, but now superior Rust-based clients like Reth offer better performance. We’re investigating how to best integrate next-gen zkEVM with Reth to elevate overall chain performance. We’ll evaluate optimal implementation strategies and migration paths should zkEVM evolve around new execution layers.

10. Nickqiao: Given Scroll’s consideration of diverse proof systems, is there value in deploying multiple verifier contracts on-chain — e.g., cross-verification?

Ye Zhang: These are two separate questions. First, is modularization and diversification of provers worthwhile? I believe yes — being open-source, the more general-purpose our framework, the more contributors will build upon it, growing our community. External contributions naturally follow in development and tooling. Hence, creating a ZK proof framework useful not just for Scroll but for others too is meaningful.

Second, on-chain cross-verification — whether between SNARKs and STARKs — is orthogonal to proof system diversity. Few projects verify the same zkEVM block once with PLONK and again with STARK. Such duplication offers little security gain while increasing prover costs — thus rarely practiced.

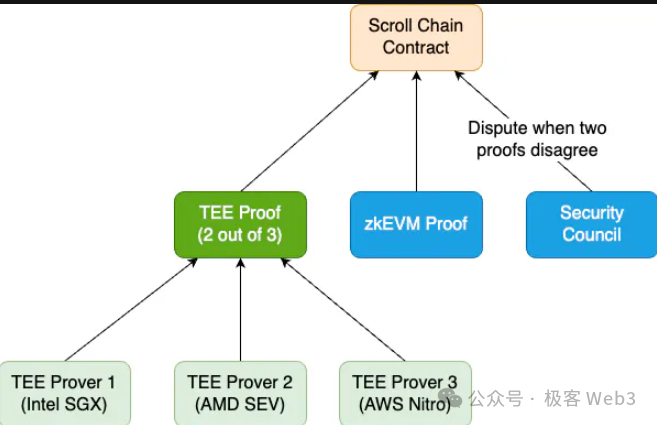

We’re building something called Multi-Prover — two independent provers simultaneously proving the same block, merging their proofs off-chain before submitting a single aggregated proof for on-chain validation. We won’t perform on-chain cross-verification between STARK and SNARK. Our multi-prover design ensures resilience: if one prover has a bug, the other continues functioning. This differs fundamentally from cross-verification.

11. Nickqiao: In Scroll’s Multi-Prover setup, how do individual provers differ in their proof procedures?

Ye Zhang: Suppose we have a standard halo2-based zkEVM with a regular prover generating ZKPs for on-chain validation. But here’s the problem: zkEVM is complex and may contain bugs. A vulnerability could be exploited — by hackers or even insiders — to generate fraudulent proofs and drain user funds.

The core idea behind Multi-Prover was first proposed by Vitalik at an event in Bogotá: if a single zkEVM might fail, run multiple heterogeneous provers in parallel. For example, alongside our standard prover, we could deploy a TEE-based prover using Intel SGX (which Scroll currently uses), or an Optimistic Prover, or a zkVM-based EVM executor. All would independently verify the validity of the same L2 block.

Suppose three distinct provers generate proofs. Only when all three pass verification — or at least two out of three — is the L2 state finalized on Ethereum. Multi-Prover ensures system resilience: if one prover fails, others compensate, enhancing overall security. Of course, drawbacks exist — notably increased operational costs. We’ve published a detailed blog explaining these trade-offs.

12. Nickqiao: Regarding ZK proof generation, how is Scroll building its proof generation network (zk mining pool)? Is it self-operated, or do you outsource computation to third parties like Cysic?

Ye Zhang: Our current design is straightforward: we want more GPU owners and miners to join our proof network (zk mining pool). Currently, however, Scroll operates the Prover Market centrally. We collaborate with third parties operating GPU clusters who run provers — but this is for mainnet stability, as decentralizing provers introduces risks.

For example, poor incentive design could result in insufficient proof generation, harming network performance. Early on, we chose a relatively centralized approach. Yet our interface and framework are designed for easy transition to decentralization. Anyone could use our tech stack to launch a decentralized prover network — just add incentives.

Still, for Scroll’s stability, our prover network remains centralized. In the future, we’ll broaden decentralization — allowing anyone to run their own prover node. We’re already collaborating with third-party platforms like Cysic and Snarkify Network to explore how developers using our stack to launch Layer2s can plug into external Prover Markets and directly access their prover services.

13. Nickqiao: Has Scroll made any investments or achievements in ZK hardware acceleration?

Ye Zhang: This ties directly to my earlier point — Scroll’s two founding pillars: first, making zkEVM possible; second, achieving it thanks to breakthroughs in ZK hardware acceleration efficiency.

Three years before starting Scroll, I began researching ZK hardware acceleration, authoring papers on ASIC and GPU acceleration. We possess deep expertise across chip and GPU levels, backed by strong credibility both academically and practically.

However, Scroll itself focuses on GPU-based hardware acceleration. We lack dedicated FPGA or hardware engineering resources and foundry experience. Thus, we partner with hardware companies like Cysic — they specialize in hardware while we concentrate on software-adjacent GPU acceleration. Our team optimizes GPU acceleration and open-sources results, allowing partners to develop specialized chips like ASICs. We frequently exchange insights and troubleshoot together.

14. Nickqiao: You mentioned Scroll might switch proof systems. Could you explain emerging ones like Nova or others — their benefits?

Ye Zhang: Yes. One internal research direction involves using smaller finite fields compatible with current proof systems — libraries like PLONKy3 enable fast operations over small fields. That’s one option: migrating from large to small fields.

We’re also studying proof systems like GKR, whose proof generation scales linearly — much more efficient complexity-wise than alternatives. But mature engineering implementations remain scarce, requiring substantial R&D investment.

GKR excels at handling repetitive computations. For example, if a signature is verified 1,000 times, GKR generates proofs far more efficiently. Polyhedra, a ZK bridge, uses GKR for signature proofs — achieving high efficiency. Since EVM contains many repetitive steps, GKR could substantially reduce ZK proof costs.

Another advantage: GKR requires significantly less computation than other systems. For example, proving a Keccak hash via PLONK or STARK requires committing and computing every intermediate variable throughout the entire process.

With GKR, you only commit to the initial input layer — intermediate parameters are implicitly represented through recursive relationships, eliminating the need to commit each variable individually — drastically reducing computation costs. The sum-check protocol underlying GKR is also adopted by newer frameworks like Jolt, Lookup arguments, and other trending systems — indicating strong potential. We’re seriously researching this direction.

Then there’s Nova, which gained popularity months ago due to its suitability for repetitive computations. Normally, proving 100 tasks incurs 100x overhead. Nova folds tasks recursively — combining pairs linearly until reaching a final composite statement. Proving this final statement validates all 100 preceding tasks, dramatically compressing overhead.

Subsequent works like HyperNova extend Nova beyond R1CS to support other circuit formats, including lookup tables — essential for VMs to be efficiently proven under Nova-like systems. Yet currently, neither Nova nor GKR are sufficiently mature for production — lacking efficient, battle-tested libraries.

Moreover, Nova’s folding mechanism represents a fundamentally different design philosophy from conventional proof systems. I view it as promising but immature — merely a candidate solution. For now, from a production-readiness standpoint, established ZK systems remain ahead. Long-term winners remain uncertain.

15. Faust: Finally, let’s discuss values. I remember you said last year after visiting Africa, you believed blockchain could achieve mass adoption in economically underdeveloped regions. Could you expand on that?

Ye Zhang: I hold a strong conviction: blockchain genuinely has utility in economically disadvantaged nations. Today’s blockchain space suffers from scams, shaking many people’s confidence — raising doubts: Why work in an industry perceived as valueless? Is blockchain actually useful? Beyond speculation or gambling, are there real, practical applications?

I believe visiting places like Africa reveals blockchain’s true potential. In countries like China or Western nations, financial systems are robust. Chinese users are happy with WeChat Pay and Alipay; the RMB is stable. There’s little need for blockchain-based payments.

But in Africa, demand for blockchain and on-chain stablecoins is real — due to severe inflation. For example, certain African countries face 20% inflation every six months — so grocery prices rise 20% biannually, compounding yearly. Their currencies depreciate rapidly, eroding savings. Many seek refuge in USD, stablecoins, or other stable foreign currencies.

Africans struggle to open bank accounts in developed countries — making stablecoins a necessity. Even without blockchain, they desire access to USD. Clearly, holding USD via stablecoins is optimal. Upon receiving salary, many instantly convert to USDT/USDC on Binance, withdrawing funds when needed — creating genuine, practical blockchain usage.

After visiting Africa, it becomes clear Binance entered early and built solidly there. Many Africans rely heavily on stablecoins — trusting exchanges more than their own national monetary systems, since locals often cannot access loans. Need $100? Banks impose cumbersome requirements, denying most applicants. But exchanges or on-chain platforms offer far greater flexibility. Thus, in Africa, blockchain meets real needs.

Most people remain unaware — Twitter users don’t care or see these realities. But in underdeveloped regions — including high-Binance-usage countries like Turkey, parts of Southeast Asia, Argentina — exchange activity is intense. Binance’s success proves strong demand for blockchain in these areas.

Therefore, I believe serving these markets and communities is essential. We have a dedicated team in Turkey and a large local community. We plan gradual expansion into Africa, Southeast Asia, Argentina. Among all Layer2s, Scroll is best positioned to succeed there — our team culture is inherently multicultural. Though founders are Chinese, our ~70-person team spans 20–30 countries, with representation across regions. In contrast, other Layer2s like OP, Base, Arbitrum are predominantly Western.

Overall, we aim to build real-use infrastructure for economically disadvantaged populations who genuinely need blockchain — adopting a “rural encirclement of cities” strategy to drive mass adoption. My Africa trip left a deep impression. Currently, Scroll’s usage cost remains somewhat high — so I hope to reduce it tenfold or more, using alternative methods to onboard users.

Let me add a possibly controversial example: Tron. Despite negative perceptions, many in developing economies use it. HTX’s exchange strategies and marketing helped Tron achieve real network effects. I believe if an Ethereum-based chain can bring these users into Ethereum’s ecosystem, it would be a monumental achievement — doing positive things for the industry. I find that deeply meaningful.

Today, many Ethereum L2s compete on TVL — chasing $600M, $700M, $1B. But more impactful news would be Tether announcing $1B in new USDT issuance on a particular L2. When a chain grows organically to that scale — capturing demand without relying on airdrop incentives — that’s true success. At least, that’s the outcome I’d be proud of: real user demand so strong that people use the chain daily.

Finally, a quick note: Scroll’s ecosystem will host many upcoming events — please follow our progress and participate in our DeFi ecosystem.

Bienvenue dans la communauté officielle TechFlow

Groupe Telegram :https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

Compte Twitter officiel :https://x.com/TechFlowPost

Compte Twitter anglais :https://x.com/BlockFlow_News