Why is the current macro environment favorable for risk assets?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Why is the current macro environment favorable for risk assets?

In the short term, be bullish on risk assets, but in the long term, remain vigilant against structural risks stemming from sovereign debt, demographic crises, and geopolitical realignment.

Author: arndxt_xo

Translation: AididiaoJP, Foresight News

In one sentence: I am bullish on risk assets in the near term, because AI capital expenditure, consumption driven by wealthier households, and still-high nominal growth are all structurally favorable for corporate earnings.

Put more simply: when borrowing costs fall, "risk assets" typically perform well.

At the same time, however, I remain deeply skeptical of the story we're currently telling about what all this means for the next decade:

-

Sovereign debt issues cannot be resolved without some combination of inflation, financial repression, or unexpected events.

-

Fertility rates and demographic structures will silently constrain real economic growth and subtly amplify political risks.

-

Asia, especially China, will increasingly define both opportunities and tail risks.

So the trend continues—keep holding those profit engines. But build a portfolio with the understanding that the path toward currency depreciation and demographic adjustment will be bumpy, not smooth.

The Illusion of Consensus

If you only read major institutions’ views, you’d think we live in the most perfect macro world:

Economic growth is “resilient,” inflation is trending toward target, artificial intelligence is a long-term tailwind, and Asia is the new engine of diversification.

HSBC’s latest Q1 2026 outlook clearly reflects this consensus: stay bullish on equities, overweight tech and communication services, bet on AI winners and Asian markets, lock in investment-grade bond yields, and use alternative and multi-asset strategies to smooth volatility.

I partially agree with this view. But if you stop here, you miss the truly important story.

Beneath the surface, the reality is:

-

A profit cycle driven by AI capital expenditure—much stronger than most realize.

-

A monetary policy transmission mechanism partially broken due to massive public debt sitting on private balance sheets.

-

Structural time bombs—sovereign debt, collapsing fertility rates, geopolitical reconfiguration—that matter little for the current quarter but are crucial for what “risk assets” mean ten years from now.

This article is my attempt to reconcile these two worlds: one being the polished, easily marketable narrative of “resilience,” the other being the messy, path-dependent macro reality.

1. Market Consensus

Let’s start with the prevailing view among institutional investors.

Their logic is simple:

-

Equity bull markets continue, but with higher volatility.

-

Diversify across sectors: overweight technology and communications, while also allocating to utilities (power demand), industrials, and financials for value and diversification.

-

Use alternatives and multi-asset strategies to manage downside—such as gold, hedge funds, private credit/equity, infrastructure, and volatility strategies.

Focus on yield opportunities:

-

Shift capital from high-yield bonds to investment-grade bonds as spreads have narrowed.

-

Increase exposure to emerging market hard-currency corporate bonds and local currency bonds to capture yield differentials and low equity correlation.

-

Utilize infrastructure and volatility strategies as inflation-hedging income sources.

Treat Asia as the core of diversification:

-

Overweight China, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea.

-

Focus themes: Asia's data center boom, China's innovation leaders, improving Asian corporate returns via buybacks/dividends/M&A, and high-quality Asian credit.

In fixed income, they explicitly favor:

-

Global investment-grade corporate bonds, which offer relatively high spreads and an opportunity to lock in yields before policy rate cuts.

-

Overweight emerging market local currency bonds for yield, potential FX gains, and low equity correlation.

-

Slight underweight global high-yield bonds due to stretched valuations and idiosyncratic credit risks.

This is textbook “late-cycle but not over”: ride the trend, diversify, let Asia, AI, and yield strategies drive your portfolio.

I believe this strategy is largely correct for the next 6–12 months. But the problem is that most macro analysis stops here—where the real risks actually begin.

2. Cracks Beneath the Surface

Macro-wise:

-

U.S. nominal spending growth is around 4–5%, directly supporting corporate revenues.

-

But the key question is: Who is consuming? Where is the money coming from?

Simply discussing declining savings rates (“consumers are running out of money”) misses the point. If wealthy households draw down deposits, increase leverage, or monetize asset gains, they can keep spending even as wage growth slows and labor markets weaken. Spending beyond income is supported by balance sheets (wealth), not income statements (current income).

This means a large portion of marginal demand comes from wealthy households with strong balance sheets—not broad-based real income growth.

This explains why data appear so contradictory:

-

Overall consumption remains strong.

-

Labor markets are gradually weakening, especially at the lower end.

-

Income and asset inequality is worsening, reinforcing this pattern.

Here, I diverge from the mainstream “resilience” narrative. The reason macro aggregates look healthy is that they are increasingly dominated by a small group at the top of the income, wealth, and capital access pyramid.

For equities, this is still positive (profits don’t care whether revenue comes from one rich person or ten poor ones). But for social stability, political climate, and long-term growth, it’s a slowly burning hazard.

3. The Stimulative Effect of AI Capital Expenditure

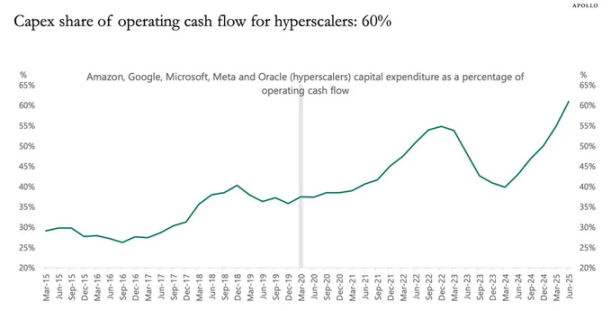

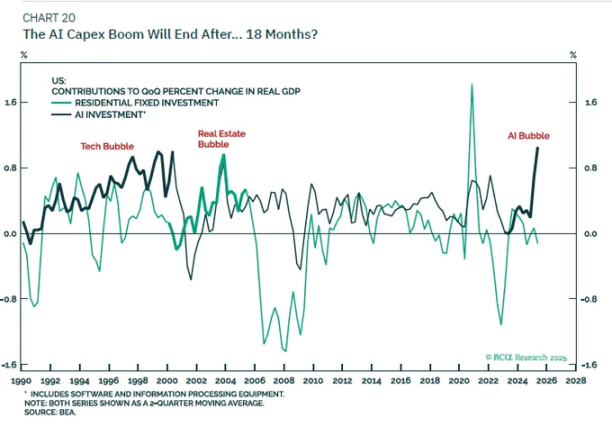

The most underestimated dynamic right now is AI capital expenditure and its impact on profits.

In simple terms:

-

Investment spending today becomes someone else’s income today.

-

The associated cost (depreciation) is spread gradually over future years.

Therefore, when AI hyperscalers and related firms significantly increase total investment (e.g., up 20%),

-

Revenues and profits receive a large, front-loaded boost.

-

Depreciation rises slowly over time, roughly in line with inflation.

-

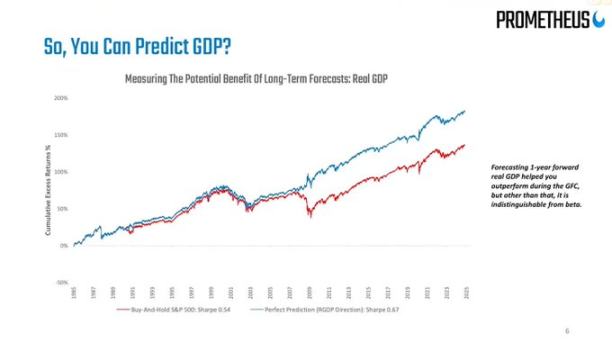

Data show that at any point in time, the single best predictor of profits is total investment minus capital consumption (depreciation).

This leads to a very simple but non-consensus conclusion: as long as the wave of AI capital expenditure persists, it acts as a stimulus to the business cycle and maximizes corporate profitability.

Don’t try to stand in front of this train.

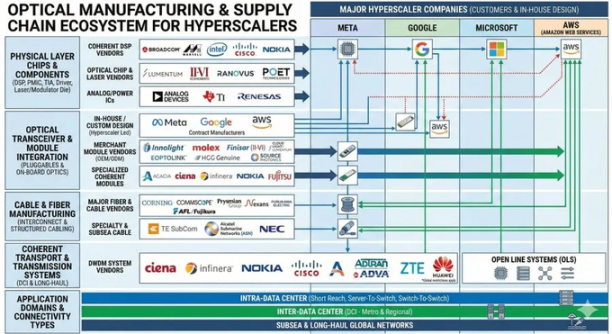

This aligns perfectly with HSBC’s overweight on tech and its theme of an “evolving AI ecosystem.” They are effectively positioning for the same profit dynamics, albeit with different framing.

What I’m more skeptical about is the narrative on its long-term impact:

I don’t believe AI capital expenditure alone can usher us into a new era of 6% real GDP growth.

Once corporate free cash flow financing windows narrow and balance sheets saturate, capex will slow.

When depreciation eventually catches up, this “profit boost” effect will fade—and we’ll revert to the underlying trend of population growth plus productivity gains, which isn’t high in developed economies.

So my stance is:

-

Tactically: remain optimistic on beneficiaries of AI capex (chips, data center infrastructure, power grids, niche software, etc.) as long as total investment data keep surging.

-

Strategically: treat this as a cyclical profit boom, not a permanent reset of trend growth rates.

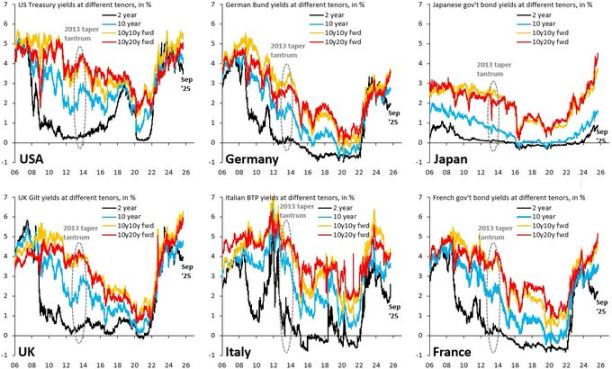

4. Bonds, Liquidity, and a Semi-Broken Transmission Mechanism

Things get weird here.

Historically, a 500-basis-point rate hike would severely hurt net interest income in the private sector. But now, trillions in public debt sit on private balance sheets as safe assets, distorting this relationship:

-

Rising rates mean higher interest income for holders of Treasuries and reserves.

-

Many households and firms have fixed-rate debt (especially mortgages).

-

The result: net interest burden for the private sector hasn’t deteriorated as much as macro models predicted.

So we face:

-

A Fed stuck between a rock and a hard place: inflation still above target, yet labor data weakening.

-

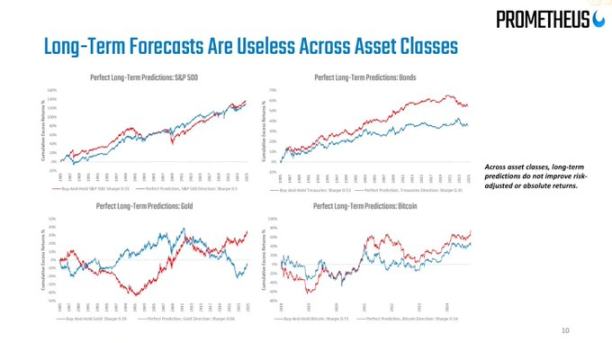

A volatile bond market: this year’s best trade has been mean reversion—buying after panic-driven selloffs, selling after sharp rallies—because the macro backdrop refuses to settle into a clear “big rate cuts” or “hike again” narrative.

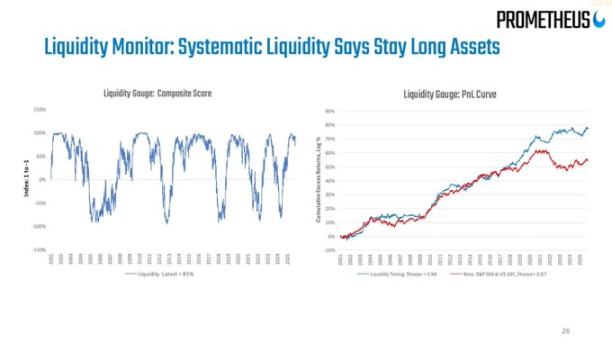

On “liquidity,” my view is straightforward:

-

The Fed’s balance sheet now functions more like a narrative tool; its net changes are too slow and too small relative to the entire financial system to serve as a reliable trading signal.

-

Real liquidity shifts happen in private-sector balance sheets and repo markets: who is borrowing, who is lending, and at what spreads.

5. Debt, Demographics, and China’s Long Shadow

Sovereign Debt: The End Is Known, the Path Isn’t

Sovereign debt issues are the defining macro theme of our time, and everyone knows the “solution” boils down to:

Reducing debt/GDP ratios to manageable levels through currency depreciation (inflation).

The open question is the path:

Orderly financial repression:

-

Maintain nominal growth > nominal interest rates,

-

Accept inflation slightly above target,

-

Gradually erode real debt burdens.

Chaotic crisis events:

-

Markets panic over unsustainable fiscal trajectories.

-

Term premiums spike suddenly.

-

Weaker sovereigns face currency crises.

Earlier this year, when fiscal concerns sent U.S. long-term Treasury yields soaring, we got a taste of this. HSBC itself noted that the “deteriorating fiscal path” narrative peaked during budget debates, then faded as the Fed shifted focus to growth concerns.

I believe this drama is far from over.

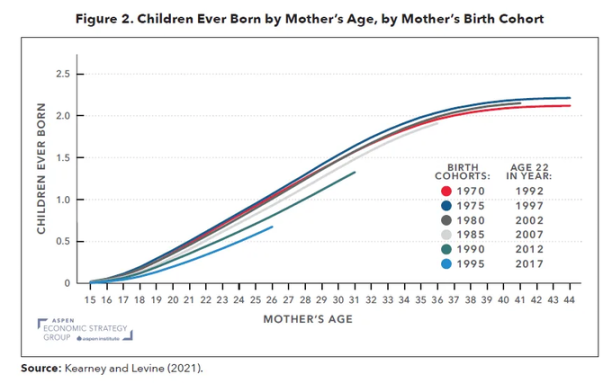

Fertility: A Slow-Motion Macro Crisis

Global fertility has fallen below replacement levels—not just in Europe and East Asia, but now also in Iran, Turkey, and parts of Africa. This is effectively a profound macro shock masked by demographic statistics.

Low fertility means:

-

Higher dependency ratios (more dependents per worker).

-

Lower long-term potential real growth.

-

Persistent social distribution pressures and political tensions as capital returns consistently outpace wage growth.

When you combine AI capital expenditure (a capital deepening shock) with falling fertility (a labor supply shock),

You get a world where:

-

Capital owners do extremely well in nominal terms.

-

Political systems become more unstable.

-

Monetary policy faces a dilemma: support growth while avoiding wage-price spiral inflation when labor finally regains pricing power.

This won’t appear on institutional 12-month outlook slides—but for a 5–15 year asset allocation horizon, it’s absolutely critical.

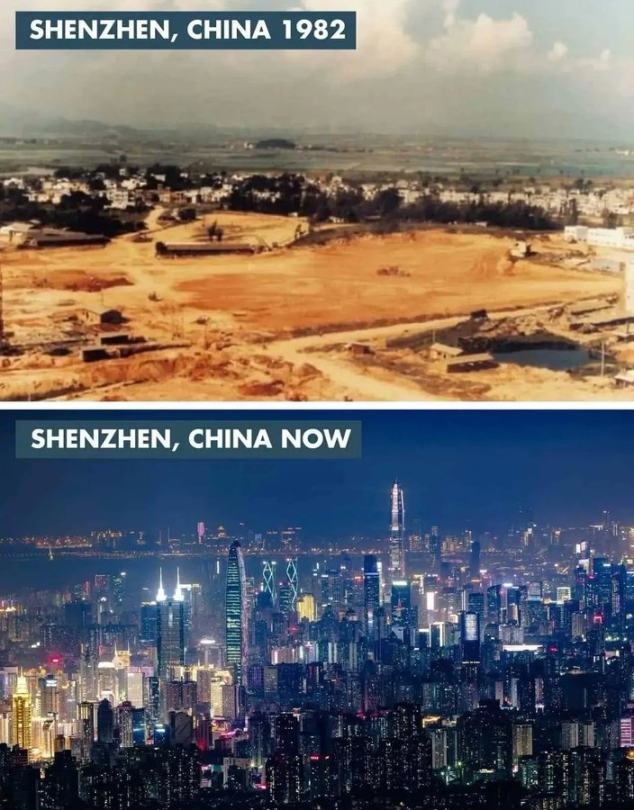

China: The Overlooked Key Variable

HSBC’s view on Asia is optimistic: supportive policies for innovation, AI cloud potential, governance reforms, higher corporate returns, cheap valuations, and tailwinds from region-wide rate cuts.

My view:

-

From a 5–10 year perspective, the risk of zero allocation to China and North Asia outweighs the risk of modest exposure.

-

From a 1–3 year view, the main risks aren’t macro fundamentals, but policy and geopolitics (sanctions, export controls, capital flow restrictions).

You can consider allocating to Chinese AI, semiconductors, data center infrastructure, and high-dividend, high-quality credit—but position sizing must be based on explicit policy risk budgets, not just historical Sharpe ratios.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News