Ray Dalio: Big bubbles and growing wealth gaps are creating greater dangers

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Ray Dalio: Big bubbles and growing wealth gaps are creating greater dangers

"Converting financial wealth into spendable money requires selling it (or collecting its returns), and this is often precisely where bubbles turn into crashes."

Author: Ray Dalio

Compiled by: TechFlow

Although I remain an active investor deeply immersed in the investment game, at this stage of my life, I also take on the role of a teacher, trying to convey my understanding of how reality works and the principles that have helped me navigate challenges. As a global macro investor with over 50 years of experience, drawing many lessons from history, much of what I share naturally relates to this field.

This article primarily explores the following points:

-

The crucial distinction between wealth and money;

-

How this distinction drives the formation and bursting of bubbles;

-

How this dynamic, accompanied by massive wealth gaps, may burst bubbles—leading not only to financial collapse but also to severe social and political upheaval.

Understanding the difference between wealth and money—and their relationship—is critical, especially regarding two aspects:

-

How bubbles form when the scale of financial wealth vastly exceeds that of money;

-

How bubbles burst when demand for money leads to selling wealth to obtain cash.

This very basic and easily understandable concept about how things work is not widely recognized, yet it has greatly aided me throughout my investing career.

The core principles to understand include:

-

Financial wealth can be created very easily, but it does not truly represent real value;

-

Financial wealth itself has no value unless converted into spendable money;

-

Converting financial wealth into spendable money requires selling it (or collecting its income), which is often precisely where bubbles turn into crashes.

Regarding "financial wealth can be created very easily, but it doesn't reflect true value", consider this example: if a startup founder now sells $50 million worth of company shares and values the company at $1 billion, that founder becomes a billionaire.

This is because the company is considered worth $1 billion, even though there isn't nearly $1 billion in actual backing behind that wealth figure. Similarly, if a buyer of publicly traded stock purchases a small number of shares from a seller at a certain price, all shares are then valued at that price, allowing the total wealth of the company to be calculated using this valuation method. Of course, these companies may not actually be worth those valuations, since asset values ultimately depend on what they can be sold for.

On “financial wealth is essentially worthless unless converted into money,” the reason is that wealth cannot be directly consumed, whereas money can.

When the scale of wealth far exceeds that of money, and wealth holders need to sell assets to obtain cash, we reach the third principle: "Converting financial wealth into spendable money requires selling it (or collecting income), which is typically where bubbles turn into crashes."

If you understand these concepts, you can see how bubbles form and how they burst into crashes—helping you anticipate and manage bubble-crash cycles.

It's also important to know that although both money and credit can be used to buy goods, they differ in the following ways:

a) Money completes transactions, while credit creates debt that must be settled later with money;

b) Credit is relatively easy to create, while only central banks can create money.

People might think purchasing goods requires money, but this isn't entirely accurate, as goods can also be bought with credit, which creates repayable debt. This is often the foundation of bubbles.

Now, let’s look at an example.

While all historical bubbles and crashes operate in fundamentally similar ways, I’ll use the 1927–1929 bubble and the 1929–1933 crash as an illustration. If you examine mechanically the late-1920s bubble, the 1929–1933 crash and Great Depression, and President Roosevelt’s actions in March 1933 to alleviate the crisis, you’ll see how the principles I’ve just described played out.

Where did bubble funding come from? How did bubbles form?

So where exactly did all the money pushing up stock prices and eventually forming bubbles come from? And what made it a bubble?

Common sense suggests that if the supply of existing money is limited and everything must be purchased with money, buying something means pulling funds from elsewhere. The thing being pulled from may fall in price due to being sold, while the purchased item rises in price.

However, in the late 1920s—and today—the driver of bubbles wasn’t money, but credit. Credit can be created without money and used to buy stocks and other assets, thereby creating bubbles. The dynamic at the time—which remains the classic pattern—was that credit was created and lent to buy stocks, generating debts that needed repayment. When the money required to service these debts exceeded the income generated by the stocks, financial assets had to be sold, causing asset prices to fall and reversing the bubble dynamic into a self-reinforcing crash.

The fundamental principles driving bubble and crash dynamics are:

When purchases of financial assets are supported by rapid credit growth, and total wealth rises significantly relative to the money supply (wealth far exceeding money), a bubble forms. When wealth needs to be sold to obtain money, a crash follows. For example, between 1929 and 1933, stocks and other assets had to be sold to pay interest on debts taken to buy them, reversing the bubble dynamic.

Naturally, the more borrowing and stock purchases occur, the better stocks perform, prompting more people to want to buy them. These buyers don’t need to sell other assets to make purchases, since they can use credit. As this behavior increases, credit tightens and interest rates rise—driven both by strong borrowing demand and the Federal Reserve allowing rates to rise (i.e., tightening monetary policy). When debts come due, stocks must be sold to raise funds, leading to falling prices, defaults, shrinking collateral values, reduced credit availability, turning the bubble into a self-reinforcing crash and ultimately triggering a Great Depression.

How do wealth disparities burst bubbles and trigger collapses?

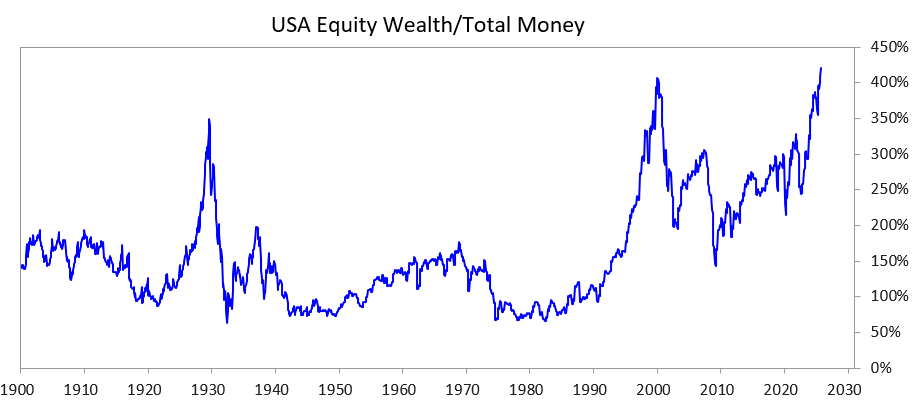

To explore how this dynamic bursts bubbles amid large wealth gaps—leading not only to financial collapse but also to social and political turmoil—I examined the following chart. It shows past and current gaps between wealth and money, specifically the ratio of total stock value to total money supply.

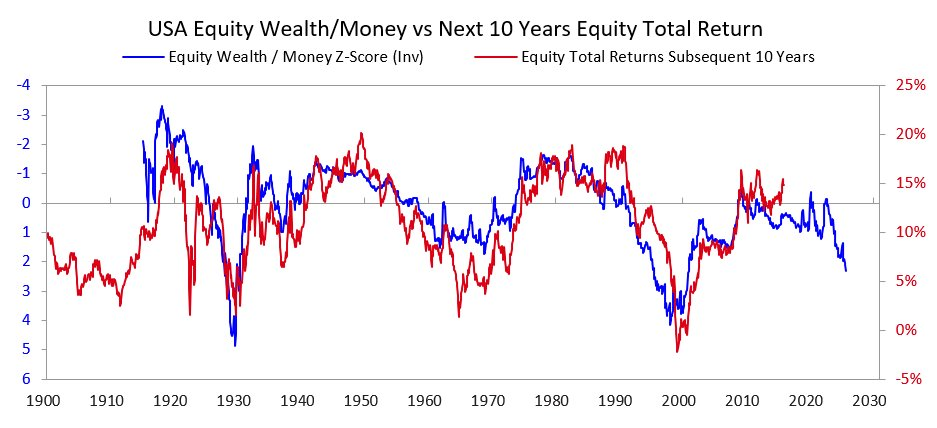

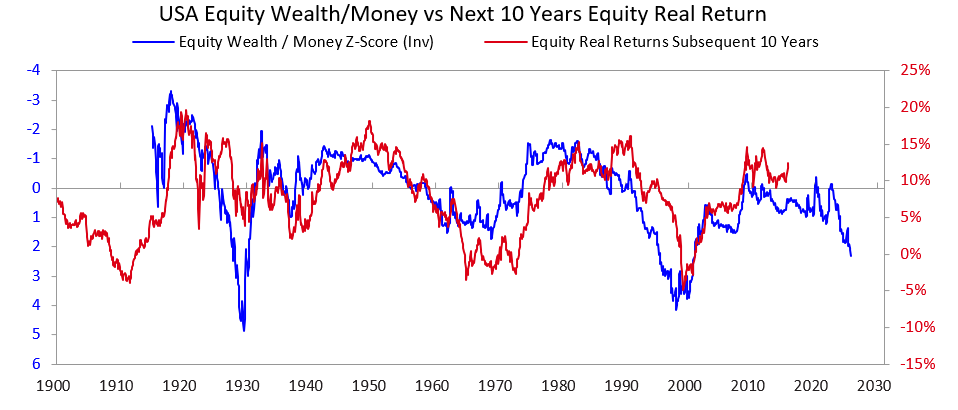

The next two charts show how this ratio serves as an indicator of nominal and real returns over the following decade. The charts themselves speak volumes.

When I hear people trying to assess whether a stock or the entire stock market is in a bubble by analyzing whether future corporate earnings could justify current prices, I realize they don’t truly understand bubble dynamics. While long-term investment returns certainly matter, that’s not the main cause of bubble bursts. Bubbles don’t burst because one morning everyone suddenly realizes income and profits aren’t sufficient to support current prices. After all, whether income and profits are enough to deliver good investment returns usually takes years or even decades to become clear.

The principle to remember is:

Bubbles burst when inflows into assets dry up, and stock or other financial asset holders need to sell those assets to obtain money for some purpose (most commonly to repay debt).

What typically happens next?

When a bubble bursts and market money and credit prove insufficient to meet the needs of financial asset holders, markets and economies decline, and internal social and political unrest usually intensifies. Especially when large wealth gaps exist, this dynamic further deepens divisions and anger between the wealthy (typically right-leaning) and the poor (typically left-leaning).

In the 1927–1933 case, this dynamic led to the Great Depression and severe internal conflict, particularly between rich and poor. These events ultimately resulted in President Hoover being ousted and President Roosevelt elected.

Naturally, when bubbles burst alongside market and economic downturns, major political changes, large fiscal deficits, and debt monetization often follow. In the 1927–1933 example, the market and economic downturn occurred from 1929 to 1932, political change came in 1932, and these shifts led President Roosevelt to begin implementing large fiscal deficits in 1933.

Roosevelt’s central bank printed vast amounts of money, depreciating the currency (e.g., against gold). This eased cash shortages and had the following effects:

a) Helped systemically important debtors meet interest payments;

b) Pushed up asset prices;

c) Stimulated economic activity.

Leaders who emerge during such times typically implement many shocking fiscal policy changes. While I can’t elaborate fully here, it’s certain these periods involve great conflict and significant wealth transfers. In Roosevelt’s case, this prompted major fiscal reforms to redistribute wealth from the top to ordinary citizens—such as raising the top marginal income tax rate from 25% in the 1920s to 79%, sharply increasing estate and gift taxes, and funding massive expansions in social programs and subsidies. These policies also sparked major domestic and international conflicts.

This is a classic dynamic. Throughout history, many leaders and central banks in numerous countries have repeated similar actions so frequently that listing them all is impossible. By the way, before 1913, the U.S. had no central bank and the government couldn’t print money, making bank failures and deflationary depressions more common. But in either case, bondholders typically fared poorly, while gold holders performed well.

While the 1927–1933 case is a classic example of an extreme bubble-burst cycle, similar dynamics appear in other periods—such as the events that led President Nixon and the Fed to take similar actions in 1971, and nearly every other bubble and crash (like Japan’s 1989–1990 bubble, the 2000 dot-com bubble, etc.). These episodes typically share other characteristics, such as attracting many inexperienced investors drawn by market popularity, who buy on leverage and ultimately suffer heavy losses and outrage.

This dynamic has persisted for millennia—whenever conditions exist where demand for money exceeds supply. Wealth must be sold for cash, bubbles burst, defaults occur, money is printed, and economic, social, and political problems follow. In short, imbalances between financial wealth (especially debt assets) and money, along with the process of converting financial wealth into money, are the root causes of bank runs—whether at private banks or government-controlled central banks. These runs either lead to defaults (mainly before the Fed’s creation) or prompt central banks to create money and credit to support institutions deemed “too big to fail,” helping them repay loans and avoid collapse.

Keep the following in mind:

When promises to deliver money (i.e., debt assets) vastly exceed available money, and financial assets must be sold to raise cash, watch for potential bubble bursts and ensure protection. For example, avoid holding large credit exposures and hold some gold as a hedge. If this occurs during a period of large wealth disparity, also beware of major political and wealth shifts, and take steps to protect yourself.

While rising interest rates and tighter credit are the most common triggers for selling assets to obtain cash, any factor increasing demand for money (e.g., wealth taxes) or prompting sales of financial wealth to meet funding needs could spark similar dynamics.

When large gaps between money and wealth coincide with unequal wealth distribution, this environment should be seen as extremely high risk—requiring extra caution.

From the 1920s to Today: The Cycle of Bubbles, Busts, and New Orders

(You may skip this section if you’re not interested in a brief history from the 1920s to present.)

While I previously mentioned how the 1920s bubble led to the 1929–1933 crash and Great Depression, to quickly add context: that crash and subsequent depression eventually led President Roosevelt in 1933 to default on the U.S. government’s promise to provide hard currency (gold) at a fixed price. The government printed大量 money, and gold rose about 70% in price.

I’ll skip over how reflation from 1933 to 1938 led to tightening in 1938; how the 1938–1939 “recession” created economic and leadership conditions, combined with geopolitical tensions as Germany and Japan challenged British and American dominance, leading to WWII; and how the classic big-cycle dynamic brought us from 1939 to 1945—when old monetary, political, and geopolitical orders collapsed and new ones emerged.

I won’t detail the reasons, but it’s important to note that these events made the U.S. extremely wealthy (holding two-thirds of the world’s money—i.e., gold) and powerful (producing half the world’s GDP and becoming the dominant military force). Thus, in the new monetary order established by the Bretton Woods agreement, currencies remained gold-backed, the dollar was tied to gold (other countries could exchange dollars for gold at $35 per ounce), and other currencies were linked to gold as well.

However, between 1944 and 1971, U.S. government spending far exceeded tax revenues, leading to massive borrowing and debt issuance—creating claims on gold far exceeding central bank reserves. Recognizing this, other countries began exchanging paper currency for gold. This tightened money and credit, prompting President Nixon in 1971 to take action similar to Roosevelt in 1933—devaluing fiat currency against gold once again, sending gold prices soaring.

In short, from then until now:

a) Government debt and its servicing costs relative to tax revenues have risen significantly, especially during 2008–2012 after the global financial crisis, and again after the 2020 pandemic-induced crisis;

b) Income and value gaps have widened to today’s extreme levels, creating irreconcilable political divisions;

c) Due to credit, debt, and speculative enthusiasm around new technologies, stock markets may be in bubble territory.

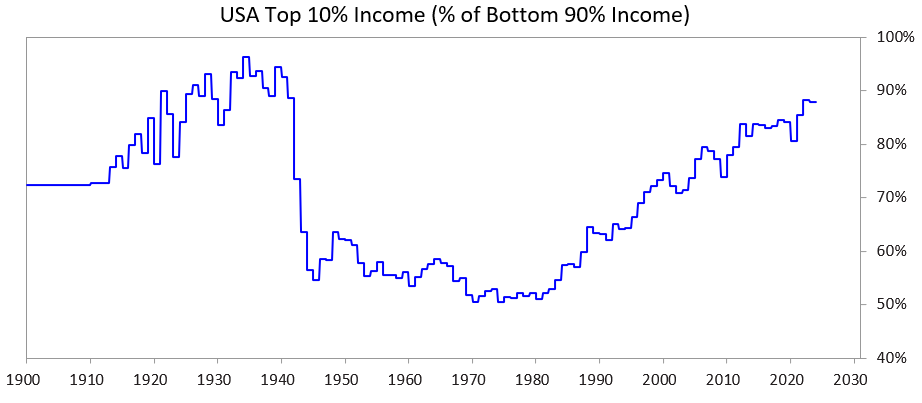

The chart below shows the income share of the top 10% versus the bottom 90%—clearly illustrating today’s enormous income gap.

Current Situation

Today, governments of democratically governed, heavily indebted countries like the U.S. face a dilemma:

a) They cannot continue increasing debt as they did in the past;

b) They cannot generate enough tax revenue to close fiscal gaps;

c) They cannot cut spending enough to eliminate deficits and stop debt growth.

They are stuck.

Detailed Breakdown

These countries cannot borrow enough because free-market demand for their debt is insufficient. (This stems from excessive debt levels and creditors already holding too much debt.) Additionally, international creditors (e.g., China) fear war-related defaults, reducing bond purchases and shifting debt holdings into gold.

They can’t solve the problem through higher taxes because taxing the top 1%-10%—where wealth is concentrated—would:

a) Risk these wealthy individuals leaving, taking their tax contributions with them;

b) Cause politicians to lose support from the top 1%-10%, whose backing is essential for expensive election campaigns;

c) Potentially burst market bubbles.

At the same time, they can’t cut enough spending and benefits, as doing so would be politically or even morally unacceptable—especially since cuts would disproportionately hurt the bottom 60%...

Thus, they are trapped.

For these reasons, all democratic nations with high debt, large wealth gaps, and deep value divides face serious challenges.

Under current conditions, combined with how democratic systems function and human nature, politicians keep promising quick fixes but fail to deliver, get rapidly ousted, replaced by new leaders who promise the same solutions, fail again, and are replaced—repeating the cycle. This is why countries like the UK and France—whose systems allow rapid leadership changes—have each had four prime ministers in the past five years.

In other words, we are witnessing the classic pattern of this phase of the “big cycle.” This dynamic is highly significant, worth deep understanding, and should now be evident.

Meanwhile, stock market and wealth booms are highly concentrated in top AI-related stocks (e.g., the “Magnificent Seven” or Mag 7) and a few ultra-rich individuals. AI is replacing human labor, worsening inequality in wealth and money distribution, and widening wealth gaps between people. Similar dynamics have occurred many times in history, and I believe significant political and social backlash is likely—potentially leading to substantial redistribution of wealth, or in worst-case scenarios, severe social and political chaos.

Next, let’s examine how this dynamic, combined with massive wealth gaps, could create problems for monetary policy and potentially trigger wealth taxes—bursting bubbles and causing economic collapse.

What Do the Data Show?

I will compare the top 10% in wealth and income to the bottom 60%, choosing the latter because they represent the majority.

In short:

-

The wealthiest (top 1%-10%) possess far more wealth, income, and stock assets than the bottom 60%.

-

For the wealthy, their gains come mostly from asset appreciation—which is untaxed until assets are sold (unlike income, which is taxed when earned).

-

With the AI boom, these disparities are growing and may accelerate further.

-

If wealth is taxed, asset sales may be required to pay the tax, potentially bursting bubbles.

More specifically:

In the U.S., the top 10% of households—well-educated and economically productive—earn about 50% of total income, own roughly two-thirds of total wealth, hold about 90% of stock assets, and pay approximately two-thirds of federal income taxes. These figures are steadily rising. In other words, their economic position is strong, and their societal contribution is significant.

In contrast, the bottom 60% have lower education levels (e.g., 60% of Americans read below sixth-grade level), lower economic productivity, collectively earn only about 30% of total income, own just around 5% of total wealth, hold about 5% of stock assets, and pay less than 5% of federal taxes. Their wealth and economic prospects are largely stagnant, placing them under financial strain.

Naturally, this situation creates immense pressure to redistribute wealth and money from the top 10% to the bottom 60%.

Although the U.S. has never implemented a wealth tax historically, calls for one are growing louder at both state and federal levels. Why impose a wealth tax now when it wasn’t done before? Simply because wealth is now concentrated there. That is, most in the top 10% became richer through untaxed wealth appreciation rather than labor income.

Wealth taxes face three major issues:

-

The wealthy can choose to relocate, taking their talent, productivity, income, wealth, and tax contributions with them—weakening the regions they leave and strengthening those they move to.

-

Wealth taxes are extremely difficult to implement (specific reasons are likely known to you, so I won’t elaborate and lengthen this piece further).

-

Wealth taxes divert funds from productive investments to government, assuming the government can effectively use these funds to make the bottom 60% more productive and wealthy—which is nearly unrealistic.

For these reasons, I’d prefer seeing an acceptable tax rate (e.g., 5%-10%) applied to unrealized capital gains—but that’s another topic for separate discussion.

P.S.: How Would a Wealth Tax Be Implemented?

I’ll explore this in more detail in future articles. Briefly, the U.S. household balance sheet shows about $150 trillion in total wealth, but less than $5 trillion in cash or deposits. So, if a 1%-2% annual wealth tax were levied, the required cash ($1–2 trillion) would exceed the available liquid pool, which is only slightly larger.

Any such policy could trigger asset bubble bursts and recessions. Of course, wealth taxes wouldn’t apply universally but would target the rich. While exact numbers won’t be detailed here, it’s clear a wealth tax could have the following impacts:

-

Force forced sales of private and public equities, depressing valuations;

-

Increase credit demand, potentially raising borrowing costs for the wealthy and broader markets;

-

Encourage shifting wealth to tax-friendly or offshore jurisdictions.

These pressures would be especially acute—and potentially trigger worse economic problems—if governments taxed unrealized gains or illiquid assets (such as private equity, venture capital holdings, or even concentrated public stock positions).

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News